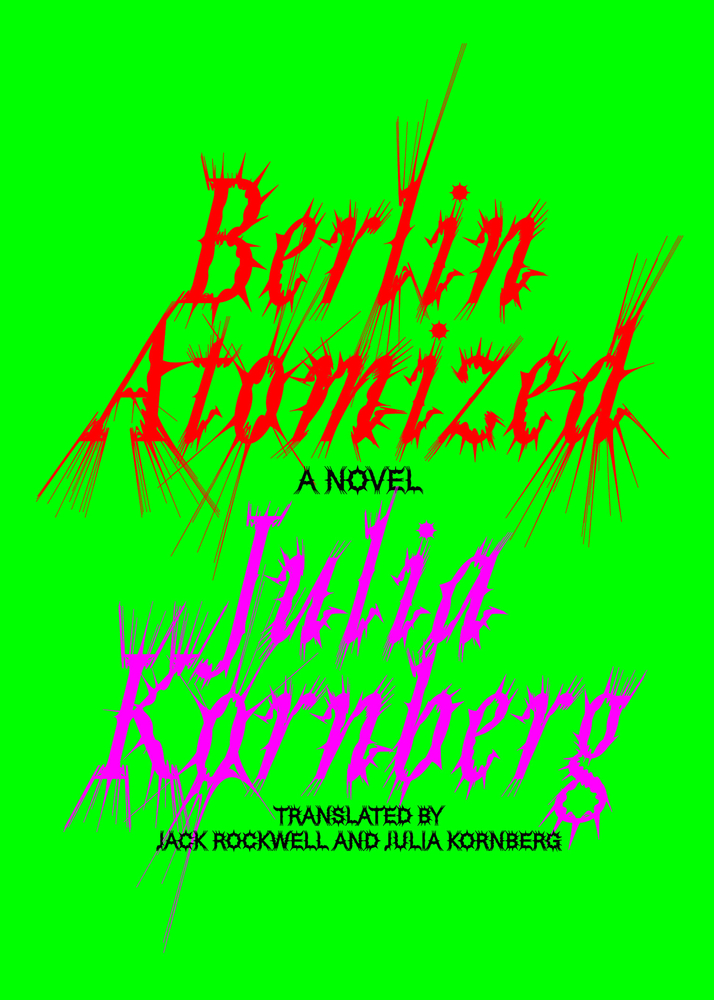

No hay tierras prometidas | Julia Kornberg’s Berlin Atomized

Reviews

By Cory Oldweiler

One of the most reliable techniques scientists have for identifying the presence of certain impurities in drinking water, soil samples, prescription drugs, and other substances is atomic absorption spectroscopy. Basically a fancy way of shining light on something and, because specific elements soak up specific wavelengths, measuring what type of light makes it through. Before a sample can be analyzed, however, it has to pass through an atomizer, usually a flame or furnace so intense that the sample both is pulverized and sheds electrons. Only in this heightened, kinetic state can scientists assess how much of the sample is undesirable and whether or not it is safe.

I don’t know whether the Argentine author Julia Kornberg had this specific science-y sense of atomization in mind when she titled her debut novel Berlin Atomized, but I found it a useful lens through which to consider her story of siblings struggling to find their places in a world that has burdened them—infected them in a sense—with soaring inequality, diminished opportunity, and alienating insularity. The novel, translated into English by Kornberg and Jack Rockwell, is presented in discreet episodes that elide critical chunks of time and told largely from the perspectives of Nina Goldstein and her older brother Jeremías, though Nina’s husband, Ossip, narrates one late chapter and her lifelong friend Angélica provides commentaries that bookend the story.

The three Goldstein siblings—Nina and Jeremías have a middle brother named Mateo—come of age in the early 2000s in Nordelta, a Buenos Aires neighborhood built on land acquired by displacing poor porteños and backfilling wetlands during the onset of Argentina’s devastating turn-of-the-millennium financial crisis, which led to intense rioting in December 2001. The novel astutely portrays the disaffection of a generation that has only known a world defined by this intensifying conflagration of gentrification, economic disparity, and environmental degradation. In a 2021 essay about the novel written shortly after the book’s publication in Spanish as Atomizato Berlin, Kornberg states that her Gen Z contemporaries see these slow-motion catastrophes as part and parcel of “la erosión de la estabilidad que nos ofrecía el mundo de nuestros padres,” the erosion of the stability that our parents’ world offered us. While the Goldsteins may grow up in a privileged enclave, instability greets them whenever they step outside Nordelta’s literal gate, and the resulting disillusionment eventually scatters the siblings. But Kornberg wanted the novel to show that “No hay tierras prometidas,” there are no promised lands, and leaving Buenos Aires—for Berlin, Paris, and Tel Aviv—does indeed prove unfulfilling for each of the Goldsteins. The novel loses its footing a bit once the setting shifts away from South America and into the speculative near future of the late 2020s and 2030s, not because Kornberg lacks deeply felt ideas about her characters and their world but because the expression of these ideas gets tangled up in and subsumed by ideology.

Nina only knows the world after “the core of Buenos Aires exploded” in the 2001 riots. When the novel opens in 2009, she is fourteen and trapped in the introspective seclusion of a latchkey kid, her parents increasingly absent (they will eventually separate), her brothers devoted to their individual rebellions. Nina feels hollowed out, repeating “I am not asleep” like a mantra while sleepwalking through large swaths of her life, obsessively lolling in the bath to beat the oppressive heat and weighing whether to lose her virginity to a blue-collar tennis coach from the conurbano south of the city. Kornberg’s imagery is captivating here, reminding me of coming-of-age films like Céline Sciamma’s Water Lilies or Sophia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides. Nina lies about what happens with the coach, and everything that comes after, even to Angélica, but her deceit lacks confidence. “The only certainty I had was the sharp guilt that enjoying it had given me, and a white sports bra covered in blood and dirt.”

The following chapter lets Jeremías, five years older than Nina, recount the formative influences in his adolescence. The only Goldstein to attend public school, on the other side of the city, Jere falls in with “Trotskyites and bohemians,” kids who “had older siblings or uncles who had been disappeared during the dictatorship; they were part of that elite sect that knew history in the flesh.” He starts drinking and doing drugs, grows out his prematurely gray hair, and, as rebellious teens have done for generations, starts a band. One night while attending a concert, he and his friends barely escape a stampede toward the stage. “Bodies fell over and onto one another in an impossible pulse of life, adolescents bursting with unthinkable drugs. My generation was stuck, my muscles defeated.” Soon after, nearly 200 teens are killed in a nightclub fire, and Jeremías gets geographically unstuck.

In the summer of 2015, he and the twenty-year-old Nina break away together, at least for a few months, taking an extended vacation across the Río de la Plata delta to Punta del Este, Uruguay. Jere is fleeing an out-of-control girlfriend and Nina is glad to be free of their mom’s critiques of her appearance. Nina rides taxis across the city, while Jere’s drug abuse drags him into a “summertime hell” that will ultimately drive him to Paris, leaving Nina on her own. It’s here the novel briefly introduces, and just as quickly concludes, Mateo’s story, his life, told through Nina’s eyes, another example of “unreachable potential.” Mateo’s a neurotic hermit by day, a libidinous hedonist with “harems of XS girls” by night. At nineteen, he is diagnosed with a terminal illness and runs away to Israel, his promised land, where he joins the IDF, to whom he likens his gated Nordelta childhood to that of Palestinians. He dies at twenty-one, under unspecified circumstances, further fracturing the family. His funeral is the last time Nina and Jere see their mom.

Nina spends her mid-twenties in Buenos Aires, working jobs she’s uncertain how she acquired and stealing alcohol to get through mindless shifts. She meets Ossip, a “forty-something-year-old German artist” from Berlin, and they begin an affair. “If our relationship hadn’t been illicit, it wouldn’t have been so hot.” After a few months, Ossip’s wife arrives to take him back home and Nina is once again alone, though this time she has finally absorbed enough knocks from the world that her isolation rousts her from the familiar confines of her homeland: “like everyone else,” she says, “leaving was my inexorable destiny.”

The translation collaboration between Kornberg and Rockwell yields particularly genuine dialogue and introduces slang Spanish terms in engaging and amusing ways. In Jeremías’s public high school, the word almond has a specific meaning: “My favorite was almond—like, literally, just the nut, but which, I found out, stood for almost, as in almost there, and they would say almond when something was only halfway or a thought was not fully cooked.” Nina’s twenty-something friends have their own lingo, too: “Candelaria doesn’t know what a pancho is, you’ll have to explain. It can’t be explained. It’s one of those things you learn by repetition. [. . .] How would you use it in a sentence? Santiago is a pancho and you need to block him.” At times, the translators’ erudition peeks through—Kornberg is a PhD candidate at Princeton University studying the role of translation in Latin American literature and Rockwell has a master’s in translation—as linguistic terms like “proparoxytone” and “syntagm” don’t often appear in a novel.

Kornberg wrote Berlin Atomized on the go (“la escribí en movimiento”), in trains, hostels, and cafes while traveling around Israel and Europe in her early twenties, stopping in Tel Aviv, London, and presumably the Western European cities that feature in the novel. What she saw, at least according to her 2021 essay about the novel, didn’t impress her: “Las ciudades europeas habían dejado de ser capitales innovadoras para convertirse en parques temáticos basados en su propio pasado, en su propia historia” (“European cities had stopped being capitals of innovation and become theme parks rooted in their individual pasts, their individual histories”). This perception of stagnation and preoccupation drives the imagined collapse of European society that motivates the latter half of Berlin Atomized. The chaos begins in 2027 in Paris, where Jeremías is a firsthand witness. He’s married and settled down, at least compared with his early European years spent playing in a band that doubled as a six-person “perpetual orgy.” The initial bombings and killings in Paris are attributed to stereotypes, terrorists yelling “AK-ALLAHU-AKBAR [sic]” while wielding “cheap, handmade weapons,” and to ethnic violence emanating from the banlieue, though there are also marauding groups of cane-wielding vigilantes ripped from A Clockwork Orange. Eventually a far-left “decentralized guerrilla warfare movement” called the New Resistance takes responsibility for the destruction aimed at “the symbols of Capital and Power, all the elite institutions propping up the status quo.”

For me, the wheels come off in the chapter inscrutably named “Akihabara, Japan.” Written only in kanji, the chapter title refers to the Tokyo neighborhood where, we learn in the novel’s brief introduction, Nina’s friend Angélica compiles Berlin Atomized in the year 2063 based on information unearthed with her hacker prowess. This extraneous framing device, revisited in Angélica’s postscript, is indicative of this thought-provoking and often quite remarkable novel’s biggest weakness, which is a tendency, especially in its second half, to get distracted by mythologizing.

The Akihabara chapter itself is narrated by Nina, now in her early forties and married to Ossip. They live in Berlin, but Nina is over it. The city has “already gone to shit,” yet (somehow?) remains “a window onto hope.” Nina leaves her husband to visit Angélica in Brussels, where Jeremías joins them. One night, their reminiscing and clothes shopping is upended when Angélica reveals herself as a New Resistance hacker mastermind, and suddenly Nina is going undercover for several months as a photographer with “an ineffectual NGO” that allows her to infiltrate “refugee camps and black sites, and from there [get] into high security prisons.” Nina’s resultant Nan Goldin–style art projects (“a photographer reimagined as a martyr, with a camera as her accusatory manifesto”) and Angélica’s revolutionary activities (breaking into intelligence agencies with flip phones and “non-wireless technology” to “force the wider public to reckon with the dark conspiracies that run the world”) are little more than word salad.

In attempting to characterize the misgivings and anger of a generation that has inherited a world that many young people see—correctly, in my view—as careening in the wrong direction, Kornberg has written an incredibly ambitious novel about a topic that is changing in real time. It has changed drastically even in the four years since she wrote Berlin Atomized. While the future imagined in her debut is unconvincing to me, the future of Kornberg as an author seems dazzlingly bright, and I can’t wait to read what she writes next.

Cory Oldweiler is an itinerant writer who focuses on literature in translation. In 2022, he served on the long-list committee for the National Book Critics Circle’s inaugural Barrios Book in Translation Prize. His work has appeared in the Boston Globe, Star Tribune, Los Angeles Review of Books, Washington Post, and other publications.

More Reviews