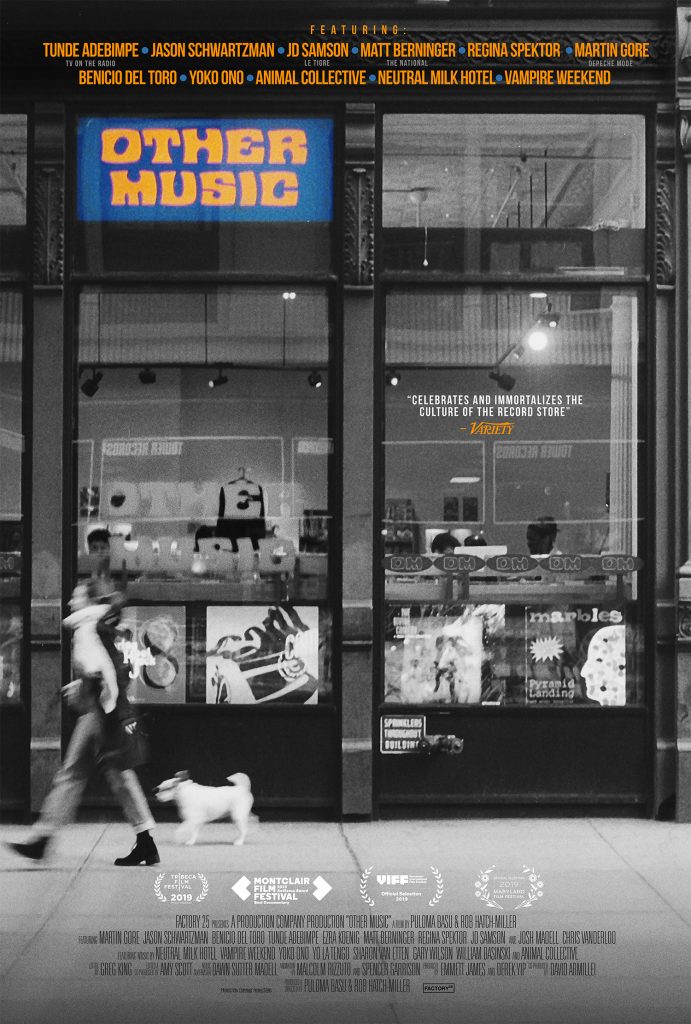

Other Music: Elegy to a Record Store

Reviews

By Wilson McBee

Oh to be browsing the shelves of a crowded record store on a warm New York City afternoon! Watching Other Music, the documentary about the life and death of the famed East Village fixture, once the scrappy upstart in the shadow of the block-long Tower Records, I couldn’t stop thinking about how, in the era of COVID-19, the movie’s tender elegy to a specific record store could become an elegy for all record stores, as well for broad categories of retail that rely on foot traffic and face-to-face interaction. Many of the experiences depicted in the film—routine just months ago—seem impossibly far away now.

In a time when so much of our experience of music happens virtually, going to a record store can feel like visiting a shrine. I still get a thrill from just picking up an LP I’ve known previously only through headphones connected to my phone. These beautiful—and fragrant!—twelve-by-twelve-inch manifestations are testaments to music’s reality in the world. Further, going into a record store bustling with customers, like attending a concert, can serve as a counter to my largely private consumption of music, a reminder of the art form’s fundamentally social character. Even when we’re listening alone, we’re not really alone. And of course, there’s the effervescent, almost-nervous feeling of packing off with a newly purchased pile of albums, getting home, turning on the turntable, and settling in for the kind of attentive listening that vinyl encourages.

Record stores can also be intimidating. To approach the register with your choices is to submit to the judgment of the record-store clerk, often imagined as occupying a nimbus of elitist disaffection. Never mind the fact that most people who work in record stores have little interest in passing judgment on their customers or playing the game of psychoanalysis through taste in music. I have known a few people over the years who manned one record store counter or another, and I can say they tend to be far more generous and open-hearted than snobby and aloof. Yet the stereotype persists, partially through High Fidelity and other pop-culture touchstones, but also, I think, through a collective sense that the fanatics and savants who work in record stores occupy such an important and lofty position that we feel they should be snobs, even if they’re not.

One of the many merits of Other Music is the light the documentary shines on what was arguably the store’s greatest asset—its people. Other Music’s two owners, Chris Vanderloo and Josh Madell, met while employees for the music department of a now-defunct New York chain called Kim’s Video and Music. Along with a third founder, who left the business after a few years, they decided to open a shop that would focus on the kind of obscure, avant-garde music they loved. Yet you can hardly imagine Vanderloo or Madell telling someone asking for Stevie Wonder’s “I Just Called to Say I Love You” that they should leave and “go to the mall.” They’re more like affable hipster dads who just happen to be into 1970s French pop and Brian Eno. With a big assist from their wives, who spent time behind the register while also helping to keep the store afloat with their own incomes, Madell and Vanderloo gathered around them a family of employees who were similarly crazy for music, and in some cases unfit for any other kind of work. And the racially diverse cast of men and women hardly hews to the standard record-store stereotype of a thickly spectacled white guy with narrow rockist tendencies. Further, the genres they promote range from dub to modern funk to Japanese electronica. One of the film’s character studies shows how the efforts of a single Other Music employee helped to revive the career of the synth-pop experimentalist Gary Wilson. In another interview an employee describes hearing the sole album made by the troubled folk singer Jackson C. Frank for the first time and being absolutely spellbound. In their interactions with customers, we see their infectious enthusiasm at work. Hardly exclusivist know-it-alls, they’re more like professional sharers or promoters of interesting sounds.

In addition to spotlighting the staff and owners, the film features interviews with artists and frequent customers of Other Music such as the National’s Matt Berninger, TV on the Radio’s Tunde Adebimpe, and Regina Spektor. The camera also captures the thoughts of customers entering and leaving the store. Curators and curation are terms that come up a lot in these conversations. Via display strategy, the in-store music selections, and even the organization of genres, record stores have the power to project a certain vision of music that is not unlike the power of a museum curator to promote their preferred historical narratives. One of the principal rewards of coming into Other Music, the film argues, was that you would be exposed to something strange and excellent that you had never heard of before. This extended to Other Music’s impressive history of in-store performances. The film features clips of artists like Jeff Mangum, Vampire Weekend, and St. Vincent playing to audiences crammed in between the store’s record shelves. Closer to a community center or a museum than a retail outlet, Other Music was not just a place where you went to buy something.

Everyone knows the story of how the internet—first through illegal downloading, then through Spotify—decimated the music industry. The film covers that story, but an observation made by an Other Music employee offers another window into the way online culture infected their business when she describes the erosion of the store’s importance as a meeting place for aficionados. “The nerds who came into the store would start their conversations online and come into the store to talk to us about it,” she says, but “then that symbiotic relationship went the other way. The conversation online kept going and stopped happening in real life.” In other words, who needed to read the thoughtfully written descriptions affixed to staff picks at Other Music when you could read Pitchfork? Who needed to go to a record store to talk about music when you could do it on message boards or social media?

Other Music was in operation from 1995 to 2016, giving it a front row seat for the end of CDs and the rebirth of vinyl. The store’s highest-earnings years came in 2000 and 2001, when buying CDs was still the primary way people accessed music. Other Music actually outlasted its two nearest big-chain competitors, the Tower Records across the street as well as the Virgin Megastore a few blocks away at Union Square, both of which had closed by the end of the century’s first decade. And while the return of vinyl has certainly been an unexpected boon for the music industry, it’s hardly a savior. Even as vinyl sales grow, they’ll never approach the numbers of peak CD; nor do they offer the same potential for profit, as described by Mac McCaughan of the label Merge Records in the documentary: “CDs were great because they don’t cost very much to make, they don’t cost very much to ship, and they can be made very quickly, and all those things are not true about vinyl.” To both the average music listener and the obsessive, vinyl records will never be essential the way CDs once were. Anyone describing the value of buying and listening to vinyl records can’t help but sound a little precious. Berninger admits that he sees buying vinyl partially as an “archival” process, reflecting the desire to acquire a physical representation of something that has been experienced digitally; the implication is that someone following that program only buys records they already like. As a mostly vinyl shop, Other Music acquired a veneer of exclusivity that it simply didn’t have before. During the CD era, a tourist from Middle America on their way to the Tower Records to buy the latest Madonna could detour into Other Music and wind up coming out with an Arthur Russell compilation. Because you have to own a functioning turntable to listen to a record, with vinyl there’s a barrier to entry that wasn’t there before.

While Other Music is mostly a story about the brutal vicissitudes of the music industry, it’s also, importantly, a story about rent. In the film Vanderloo and Madell explain that their main reason for closing Other Music was their inability to cover their increasingly astronomical monthly bills. As a low-margin business operating in the one of the hottest real estate markets in the world, inflated by a rush of speculative capital, Other Music was set up to fail. But their story is hardly unusual. Like art galleries and bookstores, record shops have a way of accelerating the very process—gentrification—that renders them unviable. As long as neoliberalism reigns, and urban storefronts are valued solely as vehicles for investment rather than sites where citizens create community, culture, and meaning, it’s hard to imagine anything about this depressing trend changing. What’s worse, the current lockdown threatens the already-precarious existence of independent retail stores throughout the country. Unable to welcome customers inside, many are trying to make do as small-time “fulfillment centers,” converting rapidly into mail-order, delivery, and curbside-pickup operations. But the revenues earned in this new environment can’t match those of the old, and meanwhile the rent still needs to be paid. It’s not hard to imagine Amazon and other big chains taking advantage of this moment—in much the same way that private equity firms were able to swallow up large parts of the housing market in the years after the 2008 financial crisis.

Only time will tell whether Other Music will come to be viewed as a document of a specific moment in time—the music scene in New York at the turn of the twenty-first century—or of a specific type of commercial establishment, the independent brick-and-mortar record store, that no longer exists. Either way, the movie will be watched. It has all the attributes of high-quality documentary filmmaking, including great characters and a powerful story. It also has an excellent soundtrack. You can stream the playlist on Spotify.

Wilson McBee is a staff writer for SwR.

More Reviews