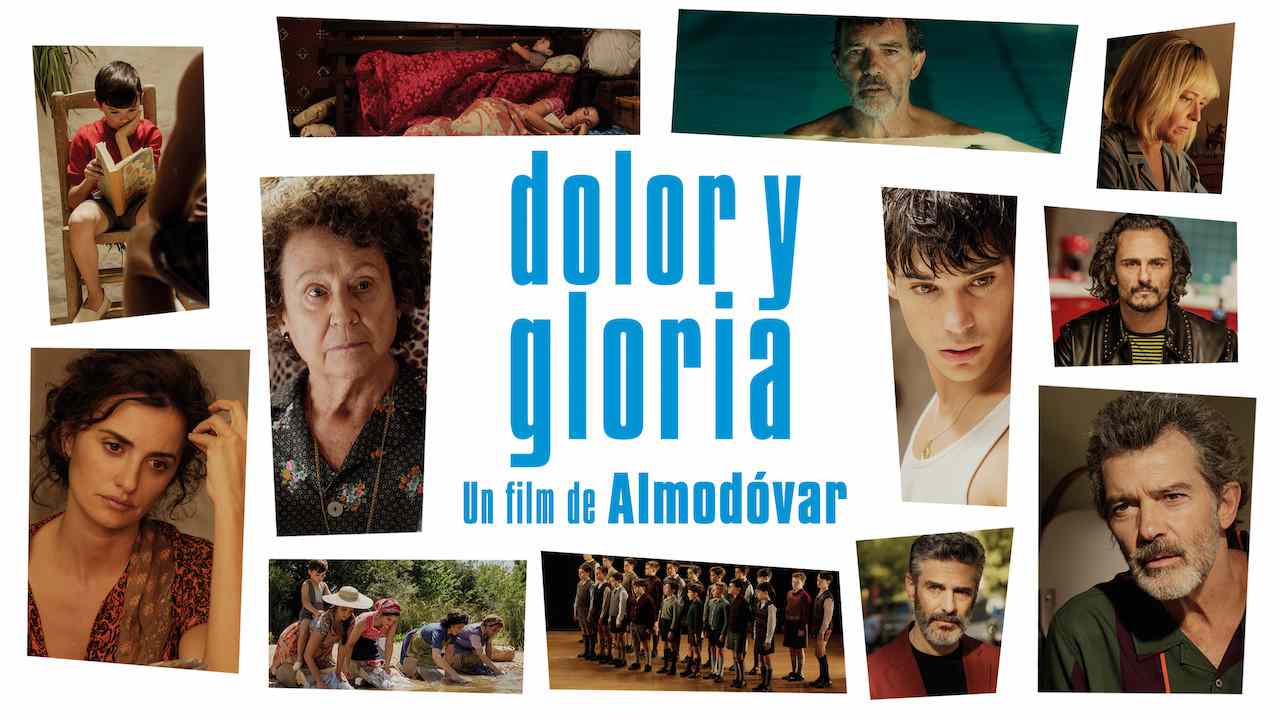

Pain and Glory | A Film by Pedro Almodóvar

Movies

By Wilson McBee

Pedro Almodóvar makes movies I want to live inside. The world of the Spanish auteur pulses with bright colors and passionate personalities. Works of art—literature, music, theater, and especially film—have real weight and significance, are things worth living and dying for. The past is never that far away; you can always count on a coincidence or chance occurrence to bring you back into contact with what you thought you had lost. And while Almodóvar is famous for blurring the lines between camp and high art, between comedy and tragedy, his films are rarely, if ever, fantastic or ridiculous. Walking out of a theater after seeing one of his movies, I often have a sense of having taken a vacation from my daily humdrum existence—and not because I’ve been exposed to a series of explosion-filled action sequences or taken back in time to witness a dramatic moment in history. Rather, Almodóvar enlivens the silly domestic world we all experience by creating characters that don’t run away from their problems but confront them directly, even if they are forced to do so by virtue of melodramatic circumstances. His films may not always be realistic, but they are always true.

If there is a letdown after watching an Almodóvar movie—oh, now I have to go back to doing laundry and filling out timesheets and repressing emotions—one can only imagine what the letdown must be after having made an Almodóvar movie, or to be more precise, after having made over twenty of them. The director’s latest, Pain and Glory, is not his first to take on autobiographical themes, but it is the first to wrestle at length with how moviemaking has affected his own life. Sporting Almodóvar’s signature spiky haircut and fluorescent-colored attire, Antonio Banderas stars as the successful Spanish director Salvador Mallo (the name is a near anagram of Almodóvar, in case anyone could overlook the physical and biographical resemblances). Following back surgery and the death of his mother, Salvador has fallen into a physical and creative rut. He winces in pain as he pads around his lonely, pristine, artwork-filled apartment. His assistant checks in occasionally, trying to spur him into getting back to work, but to no avail.

Deliverance for Salvador appears in an invitation from the Spanish Cinematheque (Spain’s national repertory theater): the institution is showing a thirty-year-old film of his, Flavor, and has asked him to participate in a Q&A afterward. After not having seen the film since its premiere due to disagreements on set with the lead actor, Alberto (Asier Etxeandia), Salvador watches the movie again and changes his opinion of Alberto’s interpretation of his screenplay. He seeks out Alberto in order to apologize and ask him to join him for the Q&A. Alberto is a functioning heroin addict, and after reconciling, the two get high together—Salvador’s first time “chasing the dragon,” in Alberto’s words. From here, the story proceeds along the lines of a typically intricate Almodóvarian plot involving a play-within-the-film, memory, recurrence, and desire. Intercut with the present-day scenes of the aging, broken Salvador are moments from his impoverished childhood in a rural village, focusing on how his mother, played with steely power by Penelope Cruz, helped push him out of his station and toward something greater.

The portrait of Salvador painted by Pain and Glory speaks to the necessary aloofness cultivated by great artists—landing somewhere between the absurdity of 8 ½ and the horror of Phantom Thread. More than either of those movies, however, Pain and Glory confronts the personal costs of making art by shining a light upon the hard choices made along the way. Banderas’s Oscar-nominated performance is a big part of this. Although Salvador views the world through empathy-filled eyes that always seem to be on the verge of tearing up, he keeps a practiced distance from everyone he encounters, as if he’s afraid of catching an airborne illness, as if he’s watching the world through a glass partition. One of the movie’s most moving scenes involves a reunion between Salvador and a former lover, Federico (Leonardo Sbaraglia), who has come back into Salvador’s life after happening to attend a one-man play, written by Salvador and performed by Alberto, about Salvador’s relationship with Federico. It was Federico’s heroin addiction that led Salvador to leave him, and in the play Salvador reckons with this decision, wondering if he could have saved Federico (at the time that he wrote the text, he didn’t know whether Federico was still alive and assumed the worst). But now he learns that Federico is drug-free, professionally successful, and living happily in Buenos Aires. As the two men drink tequila and reminisce, Federico expresses remorse for what he put Salvador through, and Salvador demurs, claiming that “it was a good learning experience” and that he “didn’t do anything that [he] didn’t want to do.” The subtext here is that however strongly Salvador may feel for Federico, he doesn’t regret losing what could have been the greatest love of his life. He had his art, after all, and that was what really mattered to him.

The British author Martin Amis once said in an interview that writers should divide their time on Earth into three roughly equal sections: reading, writing, and living. The implication is that being a sufficiently committed artist will cause you to miss out on two-thirds of life. Pain and Glory provides a number of moments in which we see how Salvador has maintained a necessary distance from experience in order to do what he does; further, we see that he has been keen to use whatever he does encounter for his art. (As the probably apocryphal Rodin quotation has it, “Nothing is a waste of time if you use the experience wisely.”) For example, when Alberto prepares to administer Salvador’s first hit of heroin, he says, “You must be doing research for something”—as if he can’t believe that Salvador would really resort to drug use out of a personal need. Later, when Salvador’s ailing mother tells him about a dream she had about someone from their village, she stops short, noticing her son’s growing interest in what she’s saying, and snaps, “Don’t look at me with that narrator’s face!” She balks at the idea that her son is using her, which—if you believe the content of the movie to be mostly autobiographical—is exactly what Salvador, or rather Almodóvar, is doing.

Wilson McBee is a staff writer for SwR.

More Movies