Perfectly Imperfect | Two Books for Analog Aficionados

Reviews

By Sam Hockley-Smith

If you really stop and think about pop music—not individual songs, but the pop music machine that is built upon endless billions of dollars being shuffled around at the top of a heap of power that, if an artist is lucky, trickles down in some fraction to them, the machine that knows why you like what you like before you even know you like it, the machine that can sell your own self-perception back to you by virtue of some kind of demographic serendipity—if you really think about this whole system, it feels . . . wrong. Misguided. The focus-grouped fine-tuning of subject matter that makes up so much modern songwriting, the scientific approach to capturing and replicating human emotion, the turns of phrase that are workshopped into the ground until life is completely sucked out of them in a misguided effort to not just capture a single emotional sentiment, but speak to an entire generation. Pop songs become hits when they connect with a bigger audience. By that point, you don’t have to think too hard about how it got made. It’d puncture the illusion.

Music is art, but it’s also commerce. Songs made by committee can be great, but sometimes you’ve listened to enough Big Idea music and witnessed too many trends and zeitgeisty phrases, and when that happens it might be a sign that you need to look elsewhere for these moments that can reorient your worldview and/or sense of self. I say this without any judgment whatsoever: not everyone feels the need to go deeper. Not everyone thinks compulsively about music or the process of creating music. That urge to go beyond what is right in front of us is a relatively rare trait. I think the general public—by which I mean anyone who doesn’t really view listening to music as an exploratory act—tends to lean on the comfort of nostalgia in these moments as a way of recapturing what they’ve temporarily lost. It’s faster and easier to go back to something you forgot you loved than it is to find something entirely new.

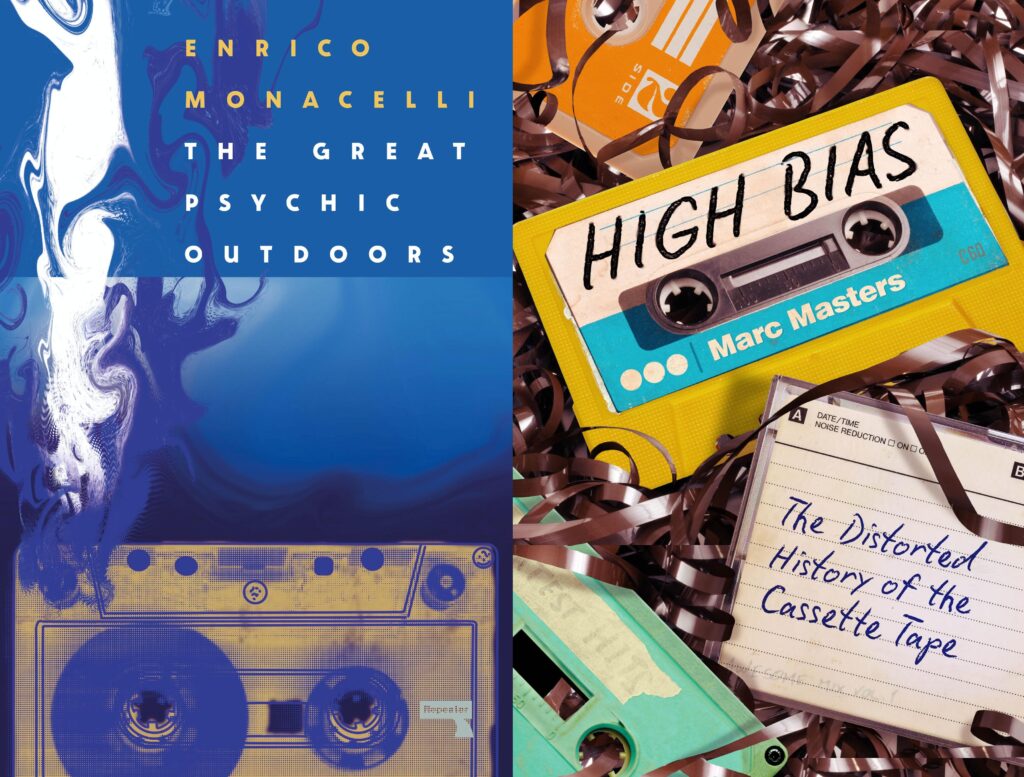

But then there’s the other subset of music listener: the person who is looking for something more specific and personal. Something that feels rough and odd. Something that feels like a secret. This is the version of lo-fi music that author Enrico Monacelli attempts to provide shape to in The Great Psychic Outdoors, and that Marc Masters explores even further via a pocket history of the cassette tape in his book High Bias. Both books can be taken together as a sort of alternate history of a time period in music when it became clear that the major-label establishment didn’t have quite as tight a grip on things as they may have thought.

But what is lo-fi music? Is it a subgenre? Is it a technique? An ethos? Somehow all of these things and none? Answering this should be theoretically simple: lo-fi music is low-fidelity music. It is music made without the pristine after-effects of a major studio. It’s often made with just an instrument and a tape recorder. It is music that sounds messed up or intimate or warped or whatever else. It’s music that was made with as little interference between the artist and our ears as possible. That concept alone—that music can be made and then released to an expectant audience without the help of the establishment music industry—means that lo-fi music, in any form it materializes, is inherently anti-capitalist, even when it is being purchased and consumed by the larger mechanisms of capitalism. But what lo-fi is and what it isn’t has been made murky over decades of language shifts and creative use. Not long ago, I listened to a report on NPR about a genre-spanning compilation of new public domain songs about safety issues. The reporter casually mentioned that there was a lo-fi track, before playing a snippet of a downtempo track that did not sound lo-fi at all.

The Great Psychic Outdoors is, loosely, a corrective. An effort to pin down not just what lo-fi is, but why it matters, and how it can lend a naive approach to the act of creation that can spawn sonic revolutions or, in some cases, quietly shift the entire course of music in often imperceptible ways.

By its nature, The Great Psychic Outdoors cannot be fully comprehensive—can you imagine trying to write about every “lo-fi” artist, especially when the phrase has evolved to be malleable enough to describe someone making beats in their bedroom (not inherently lo-fi)? The book would never be finished. Instead, Monacelli cherry-picks artists in order to illustrate his thesis. That means we do not get to read about Lou Barlow’s early tape experiments. We do not get a deep dive into Guided by Voices. There is no chapter dedicated to the early recordings of Three 6 Mafia. Monacelli frames this right up front. It is a useful way to ward off angry completists while also writing the type of book that we don’t often see anymore: this is music writing as a search for universal truth, an excavation of enthusiasm and quixotic goals that inspires and acts as a warning in equal measure. It favors passion over authority, and the more I dwell on it, the more that seems like the right way to speak about music that flouts the traditional structures—power, distribution—as a matter of course.

Because lo-fi is a technique that masquerades as a genre, there’s not always a whole lot of commonality between the artists Monacelli writes about. Instead, he grounds their decisions in how their approach exists outside of—and sometimes spits in the face of—the conventional strictures of the music industry at large. From the chapter on R. Stevie Moore:

This lo-fi ethos illuminates the real nature and significance of R. Stevie Moore’s anarchic sincerity, his willingness to put all of his life on tape. Lo-fi unveils the paradoxical, proper meaning of those baffling bathroom skits and chaotic pop songs. In a sense, in light of his staunch lo-fi militancy, it is quite apparent that his way of including everything in his albums was not something that happened naturally, so to speak. Or, in other words, it was not just a matter of simply saying what he had on his mind. It was, more accurately, a direct consequence of his combative choice to subvert and attack the dominant productive paradigm in the sonic arts: the squeaky-clean studio album, the orderly discography and intelligible persona.

Later, Monacelli questions whether the sincerity inherent in this approach is a style of its own or a consequence of Moore’s decision to record how he recorded and release virtually everything he put to tape. In the case of Moore, the answer to that question is murky, especially when Monacelli imbues his process with the sort of punk anti-establishment ethos that tends to act as a thrust for so much music that exists outside the mainstream. As time goes on, and as lo-fi becomes less a necessity and more a choice (it’s significantly easier to record “clean” audio at home than it was even a decade ago), it’s safe to say that this line of questioning leads toward the style end of the spectrum: You can be on a major label and record a lo-fi album. You can have a huge hit that sounds like someone dropped a record in a trash compactor and then tried to play the pieces. You probably won’t, but you can.

Though he leaves a lot on the table, Monacelli is canny in his choice of artists to cover: we get a full chapter on Ariel Pink’s output and persona, including most of his extremely regrettable decisions. We follow Mount Eerie’s Phil Elverum into the Norwegian wilderness to track the recording of Dawn, which sounds clean but was recorded in a tiny cabin in the middle of nowhere amid a barebones existence that can only be described as lo-fi living. We get enthusiastic insight into Daniel Johnston’s lo-fi cult mysticism. If you’re looking for a survey of what lo-fi used to mean, what it means now, and what it could mean in the future, you’ll get a lot out of this book. If you’re looking for inspiration and a rough guide to creation outside of the main channels, you’ll also find a wealth of that here. It’s not complete, but it doesn’t need to be. Taken as a whole, The Great Psychic Outdoors is a portrait of creation in the face of impossibility, of art rising from frustration and sometimes desperation. It’s a fun read, but it’s also a guide to how to remain pure as the music industry crumbles and reforms around us.

In his book High Bias, the writer Marc Masters excavates the history of cassette tapes, choosing to focus on the way they disrupted and democratized music. It’s easy to forget—and at this point many people probably don’t know at all—that according to the recording industry, cassettes once posed a genuine threat to the recording industry. Would people still buy records if you could simply dub a record to a cassette and give it away for free? Would people still listen to the radio if they could record all their favorite songs from the radio onto cassettes to listen to whenever they desired? With hindsight, we know that cassettes did not destroy the music industry—if anything, the mixes and homemade compilations people dedicated hours and months and years of their lives to making made more people lifelong music fans, more predisposed to buying music than they otherwise would have been.

In fact, if there’s a through line besides the actual form of the cassette in High Bias, it’s that the medium engendered enthusiasm that turned into obsession—the act of, say, recording songs off the radio became an art form in itself. And the actual object—the plastic cassette—a tactile artifact of the pre-internet age, already revitalized and romanticized in popular culture, a means of rebellion in the face of gatekeepers who wanted music to be recorded and sold in a specific way, took on an outsized importance. Could that small rectangle be the end times for the music industry as it was then? The answer is, of course, no, but it does still remain significant today for largely the same reasons it was significant upon its introduction: it democratizes music. The sharing of it, the recording of it, the communication about it. You can kinda see why those in power got spooked.

This is fundamentally the premise Masters uses throughout the book. Much like Monacelli, he recognizes that a comprehensive book about the cassette would be a fool’s errand—its history is pocked with odd detours, each with enough material to fill another book, and our relationship to the format is still growing and changing to this day—so instead he couches it against the idea of sonic revolution. Think Bruce Springsteen desperately trying to recapture the lo-fi minimal-overdub approach of his Nebraska demos:

He kept pulling out that cassette and saying, “I want it to sound more like this. . . . There’s just something about the atmosphere on this tape,” studio engineer Tony Scott told Tascam. Another engineer, Chuck Plotkin, described Springsteen’s re-recording woes to biographer Dave Marsh this way: “The better it sounded, the worse it sounded.”

Masters is smart to reference Nebraska, not just for the way it was recorded, but for how its release involved Springsteen fighting against his own creative signature: gone was all the maximalism and bombast, and in its place was a rough, desperate, dark work of art that thrived because of its imperfection. The flaws were the point.

Masters wisely eschews a comprehensive history of the cassette in favor of zooming in on a couple of its traits that feel especially relevant today. By beginning the book with the now-quaint cassette tape panic and documenting its journey through the hands of mixtape-making obsessives, the rise and fall and rise (again) of tapes in the twenty-first century has taken on something of a dual meaning: nostalgic totem and physical tether to a digital world. In doing this, he’s able to capture what is ultimately special about the format: the ability to dictate and share music where and how you want to.

Increasingly, music is siloed to the point that it’s a solitary experience, even if you wish it were communal. If you subscribe to a major streaming service, you can share the songs you’re excited about with only your friends who also subscribe to that service. Common ground based on aural aesthetics is now secondary to where your ten bucks a month goes. Is it even possible for a scene to rise up from the common ground of, uh, “subscribing to Spotify”? Both Masters and Monacelli, in focusing on not just an analog medium, but the way an analog medium exists outside the strictures of what the corporate music industry allows, have zeroed in on what is fundamentally lacking from music today: community.

This is not to say that community is gone entirely. Masters, in particular, goes to great lengths to document small labels who’ve used cassette culture as a way to carve out a distinct space for themselves in a very crowded field where community has been de-emphasized in favor of an overly tailored listening experience.

If you’ve ever asked yourself, “Why would I need someone to recommend music to me? I already know what I like,” then you are apparently, unfortunately, the majority. A loss of curiosity means a loss of vitality, and both Masters and Monacelli, in speaking about a component of the industry that exists under and in tandem with the major-label world, are showing us a way forward by looking back at the recent past. In fact, both High Bias and The Great Psychic Outdoors are so effective at conveying lawless enthusiasm, a total disregard for the “rules” of music, and unvarnished creativity that they immediately brought back a formative memory.

In the mid-1990s, I lived in a cable-free household. This meant that MTV, a vital part of culture at the time, was mostly not available to me. My way to get access to MTV was to go to my friend’s house after school a couple days a week and binge-watch an endless stream of videos: White Zombie into Janet Jackson into Better Than Ezra into Live (during that period when singer Ed Kowalczyk had a bald head with just one long braid coming off the back). When I went home, I was desperate to hear those songs again, so I’d load a tape into my stereo and wait for them to appear on the radio. Usually they did, but not always. My solution was to place a small boombox directly in front of my friend’s TV and record the audio from the music video to the cassette. This meant that my memories of these songs are forever intertwined with snatches of kid dialogue. A friend shouting “Woo!” over the chorus of Better Than Ezra’s “Good,” the sound of a glass shattering in tandem with White Zombie’s “More Human Than Human” as a result of aggressive living room headbanging. These imperfections became indelible parts of my listening history. The songs are inseparable from the poorly recorded versions I’d made. I don’t hear those songs much these days, but when I do, the personal moments are tangled up in there, even though I don’t get to hear them anymore. The memories are still real. Perfectly imperfect. Flawed. Mine. Ours.

Sam Hockley-Smith is a writer, editor, and radio host based in Los Angeles. His work has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, the FADER, Pitchfork, NPR, SSENSE, Bandcamp, Vulture, and more. His radio show, New Environments, airs monthly on Dublab. He spends his spare time reading.

More Reviews