Radical Geometry | A Conversation with José Vadi

Interviews

By Kyle Beachy

Isn’t it nice, a little heartening even, when they get something right? In reviewing essayist, playwright, and poet José Vadi’s 2021 collection, Inter State (Soft Skull), the Los Angeles Times called the author “someone you’d want to have a beer with.” Hard agree.

I first met José in the vast, partitioned parking lot under the tracks of the Rockridge BART station, in Oakland, in the summer of 2021, not long before Inter State’s release. We pushed around for a time, filmed each other, then went for beers. Within days, he and his wife would be moving from the city he loves to Sacramento. Within a month, he’d be a virtual interlocutor for my own book release at Green Apple, in San Francisco.

Having those beers with José was a joy. Likewise reading José in 2021, as the LA Times and others agreed. His first book was a kind of anti-Didionic approach to what the industry calls “writing California,” which for José Vadi means tracing his grandfather’s history as a migrant farmworker in the Central Valley and, more generally, bearing witness to the collective memories of the state, from “1950s surfer stereotypes” through the “riots and smog alerts and blackouts culminating in the ’90s.” Among these memories are more than a few about skateboarding, a pursuit that’s as woven into José’s identity as his Mexican and Puerto Rican parents, his omnivorous love for music, and even, yes, literature.

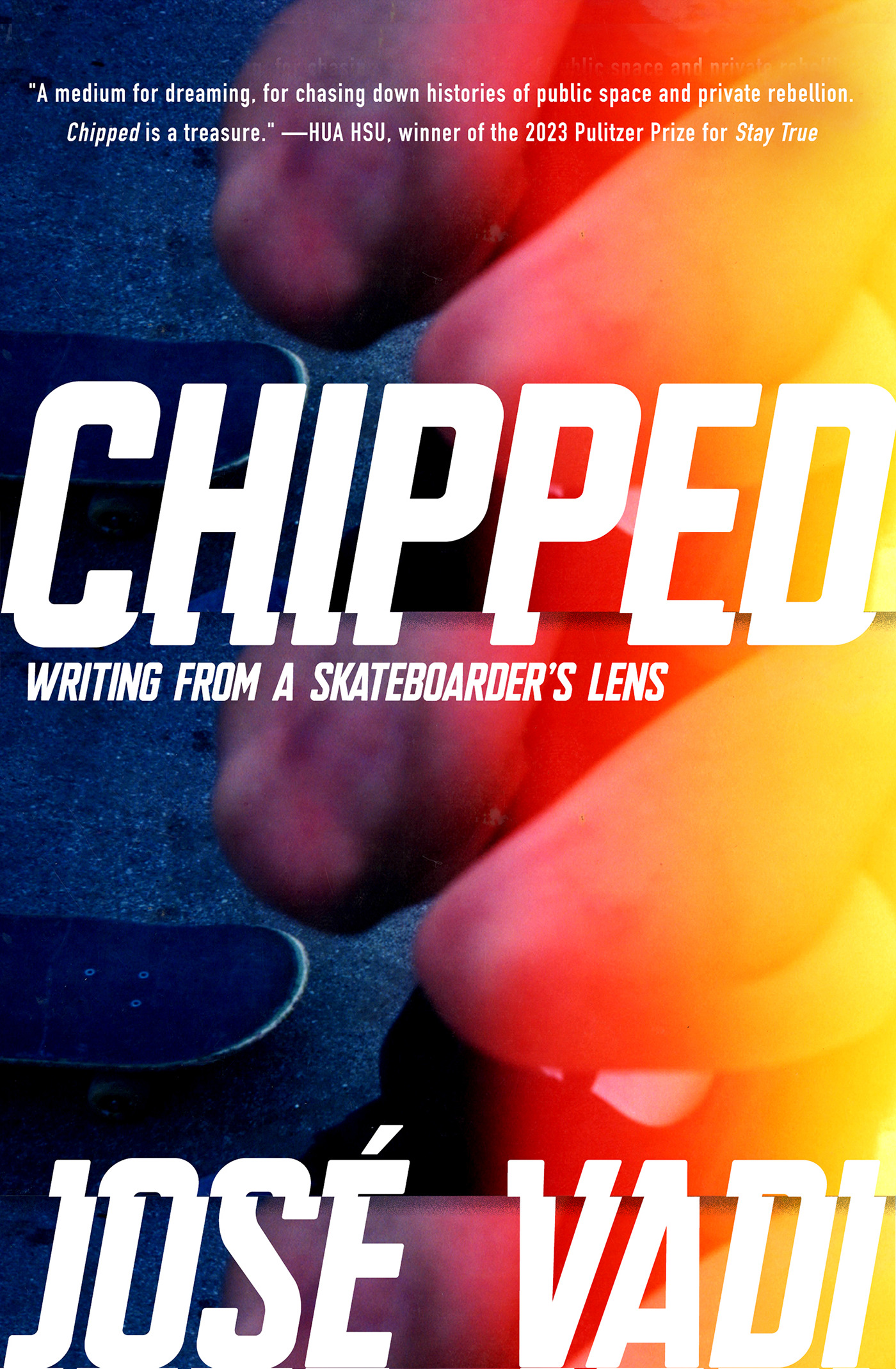

Now Soft Skull has released José’s second collection of essays, Chipped, which tightens the author’s focus on Rockridge and the unloved spaces where skateboarding has lived. Like its predecessor, Chipped employs a kind of radical geometry. Each chapter surrounds its subjects and comes at them from a surprising sequence of angles. Hua Hsu calls the book “a treasure” and I couldn’t agree more; the chapters are personal and historical and inquisitive, and most impressively, they are also generous. Inviting.

Which is not a way that skateboard culture has traditionally been. Somehow, Chipped manages to engage all of skateboarding’s rougher realities—the shit talk and middle fingers, the wounds and hero worship, the jargon and brands and overzealous police—without indulging the exclusivity that, for years, was a source of skaterly pride. Nor has José reduced skateboarding, or defanged “it” in the name of broader appeal. The result is a book that’s inclusive in the word’s best sense, girded by a prevailing and unwavering respect for its reader.

With the successful invitation of Chipped in mind, José and I engaged in the following Q&A at what I’ll call a “skater’s pace.”

Kyle Beachy: In the introduction to Chipped, you describe Inter State as “an exercise in writing from a specific place at a specific moment in that place.” I wonder if we might start by talking about specificity and how it relates to the movements and dynamisms that one feels from your prose.

José Vadi: I think that specificity in Inter State had to do with this claustrophobic feeling I had while writing the book.

José Vadi: I think that specificity in Inter State had to do with this claustrophobic feeling I had while writing the book.

Do you remember that Flaming Lips album Transmissions from the Satellite Heart? I always loved that title, thinking about the band playing live on some distant satellite and us, somehow, listening to it via compact disc. I thought about that a lot when writing Inter State—from my desk in my kitchen, on BART between SF and Oakland, driving through the Central Valley—sure, in an essay, I’m crossing a lot of histories and physical places, but as a writer, I felt like this satellite sending Morse code signals to the reader via Inter State, almost like a “reporting live from south of Market, here’s this new essay from José Vadi” kind of feeling. Like a DJ announcing the next song between traffic updates. Maybe it was the feeling of writing from a small desk and screaming out to the world, not knowing if Inter State would even get published.

I was taught as a poet to move a lot when you write, and I wasn’t doing that with Inter State—like I would walk around all day to exhaust myself enough to write—so when I did sit down to write, I wanted it to be emblematic of the energy of everything I had traversed that day.

Ultimately, I really wanted people to feel close to the places I was navigating through Inter State. Even in the copyediting, I remember telling Soft Skull to leave the names of streets according to how they look in real life, not what the copy guide suggests. So if it’s a number on the signs, it’s a number on the page; letters on the sign, letters on the page. I don’t know how effective that was in translating place onto the page, but I wanted to at least have the experiences be consistent.

KB: Can you speak a bit about writing poetry, and maybe genre more broadly? How does your poetry practice fit into this book? Or your playwriting, for that matter?

JV: Poetry’s just endless, so many forms within a form. But I think I developed a sense of timing and cadence through poetry, or at the very least, it helped define how I approach language as something I had agency over. Lots of memories of remembering spoken-word poems, but also rap lyrics, come to mind, this relationship with words and their performance. I should note that I really got into poetry through live performances, open mics and slams, and not a traditional literary academic program. Which speaks to that scene’s intersection with what was, at the time, called “hip-hop theater.”

But regarding place, I feel like playwriting allowed me to understand how to develop a place within and without constraints, from the physical limitations of a stage to even the physical demand of performing a particularly extensive monologue—the many different factors at play when writing something that can be eventually executed and performed. That was interesting because it’s bringing a world to life from a point of isolation when you’re writing alone. And building that trust as a playwright to describe the vision, the why of a script, to others (actors, producers, grant writers) and then demonstrate the vision through the prose, that was all super interesting to explore basically through the end of undergrad at Cal through my mid-twenties, before diving into nonfiction in grad school at Mills College.

Both poetry and playwriting are palpable, for me at least, throughout Chipped. Like the beginning of “King Shit” has a monologue energy to it, and the moments in “Programming Injection” where I use all caps to demonstrate these moments of feeling like an adult have a stage direction energy to them that, again for me, recall certain aspects of playwriting. Even the opening of my first book, Inter State, has that stage direction, too, this opening of a scene of me filming my grandfather.

Ultimately, I think poetry shaped my voice, and playwriting my relationship with dialogue (and vis-à-vis sonics) and space.

KB: Unlike Inter State, whose route into existence was accumulative, Chipped was conceptualized as a book from the outset. What was it like to write in this way, under contract with Soft Skull and with a book as your goal? What changes when we think of our work in progress as chapters rather than essays?

JV: Writing under contract for a project this size is something I hadn’t experienced since 2008 when I wrote my first play and knew I had to write it, produce it, perform it.

I have a team at Soft Skull that I really enjoy working with, but the pressure for Chipped at times felt immense and that pressure was very much self-administered. Most of my revisions were nearly full rewrites of essays, sometimes ignoring line edits that I received and figuring “It’ll be better if I just rewrite all of this.” During meetings with my editors, I just remember telling Mensah Demary and Cecilia Flores, “It just needs to be good,” whatever the hell that means or meant at the time; I was definitely writing as much of that idea as possible in those early drafts.

Inter State taught me how to write at scale as a nonfiction writer, and I enjoyed writing bigger essays like the titular piece as well as shorter, snapshot-of-life pieces like “Getting to Suzy’s” and seeing how the two could speak to each other within an essay collection. With Chipped, I wanted to see what that size and scale could look like with whatever chops I’d felt I’d developed since Inter State, and certain ideas in that first book begat scenes in the second. Like imagining Sun Ra being a skateboarder, doing heelflips over cars, was motivated by the daydream in the essay “Inter State” of my grandfather smoking WWII-era marijuana and then lighting a crop on fire. How could the daydream as a device inspire an entire nonfiction piece versus being an aside within one?

So I was originally thinking Chipped would be a handful of essays, like three or five massive essays. “Curbs” and “King Shit”—the essay about Sun Ra and Sage Elsesser and Jackie McLean—were originally going to be one essay. Which may have been a bit too Mars Volta in hindsight, but I needed time to explore and research and find a path, and to encourage myself to think bigger, identify more intersections between these non-skate examples—music, film, histories of cities—and skateboarding. It’s not surprising I tackled what would be the biggest projects first—“King Shit”; “Programming Injection,” about Ed Templeton’s art and its impact; “Wild in the Streets,” about an Emerica demo and metal show in San Francisco on the Fourth of July—and grappled with them the most. There’s a lot on the cutting-room floor for all three.

Inter State I kept pretty close to the chest. I kept telling friends about “the book” for years without ever showing it to anyone but Mensah and my wife. Whereas with Chipped, I shared early ideas with some friends and opened myself up to that vulnerability. And I think that helped a lot, trying to articulate the idea for the book’s essays/chapters to friends who skate and write.

Coming up with the title Chipped early into the project helped create a living thesis statement. I always knew what that term meant to me, or how I responded to it, but trying to write from that idea helped make every new part of the book relate to each other, no matter how disparate the subject matter.

KB: The type of revision you’ve described aligns with all the doing and undoing and repetitions that comprise the activity of skating.

JV: That comparison doesn’t sound like a stretch. Whether it’s trying to land a trick a certain way or have a scene or sentence land a certain way on the page, I think both of those paths are trying to best reflect the idea we have of those final products in our head. We’re trying to actualize the visual in our mind of how we execute the trick or the writing.

In Inter State, I really wanted things to sound like a conversation, very much an across-the-table proximity to the reader. With Chipped, I wanted the prose to be more of a presented argument versus a well-sourced scream, which so many of the essays of Inter State feel like to me and was somewhat a goal of that project, too. Which is to say that the approach to some of the writing of Chipped just took more tries, back to the skate-trick comparison. I just needed more tries to tackle something like “Programming Injection” or “King Shit” the way I wanted those first drafts to appear on the page. Or even something shorter and more rooted in defining a term, like the essay “Chipped.” Starting from scratch versus picking away at certain lines just felt right and, I hope, helped to build a more consistent voice across the chapters and book.

KB: I always admire the kinesis of your writing—it reminds me of early Rebecca Solnit, the era of A Field Guide to Getting Lost, except moving on wheels rather than by foot. You turn to a few key metaphors to keep essays from spinning off into space, but still, it can feel a little magical, the fact that these essays adhere. What is it that’s keeping them together, in your eyes?

JV: Part of that glue is definitely the verbiage itself. Some of these terms-turned-metaphors are rooted in non-skate life. Leveraging those as bridges through the prose of Chipped helps me navigate other diversions I have where I don’t guide the reader as much. And I think that comes from just years of writing poetry, and encouraging the disruption of form and trying to speak from those new places. Accepting that place of vulnerability as the starting place for the prose.

And also, trying to reflect the tone I want to create for the reader engaging with the material. Most days, I feel pretty overwhelmed and hyperaware. Writing forces me to sit down and articulate as many of my strands of thought as possible, shaped by the energies of the idea, in a sense. I want the prose to reflect that energy into its form.

KB: In “Sick Boy,” you describe a moment of injury, which is necessary to anyone who wants to pursue skateboarding. Injury is to skating what rejection is to writing. “Most of my life,” you say, “has been spent mumbling across dinner tables” and in other “unamplified interactions.” But on this day, after this injury, you yell in a “new voice, previously unknown to my ears and lungs.” What is this new voice?

JV: In the most literal sense I was trying to describe the very public scream I had falling at that moment. Which is funny because there wasn’t too much physical pain, the scream was almost an articulation of my psyche, realizing my error and the folly of trying to do something my body probably shouldn’t have done that day. I still mumble through a lot of life, let’s say, but I think as skaters we mark so much of life by our injuries and the impact it has on our psyche. There’s a before and after, a learning, however unwelcome. But whatever new voice was created in that moment in “Sick Boys” became the voice in “Curbs” that’s at Rockridge BART, learning how to be vulnerable again, humbling myself to the reality of learning slappies. Of trying.

KB: On the far side of injury and yelling is the “realized joy” that can come from skating. Your family plays a particularly beautiful role in the book, first for the care and concern they show for young José, and also for the way the effects of this care has lived with you into your authorship. Can you talk a little bit about what skateboarding has meant for your relationship with them?

JV: I think skateboarding provided them with an example of something I was really passionate about. Something that I wanted to impact me and that I wanted to pursue as much as possible. For them, they may have compared it to their own childhood experiences of fighting for the right to listen to the kind of music they wanted to or to dress a certain way, or even just the ability to leave home without massive guilt. But that passion I had for skating forced them to have to figure out a way to reconcile with the fact that, in their eyes, skateboarding made me public enemy number one in the eyes of police or whoever else on the streets—and I was on the streets!

Skateboarding was basically the thing in our lives that engendered a new trust between us. It’s like both parent and kid recognize the better sides of each other’s stubbornness and find ways to compromise.

But I think their recognizing songs from the ’60s and ’70s in skate videos was a big part of that, or me showing them skate magazines and them hearing me describe why I thought certain photos were better than others. I appreciated them asking me Why? They could see that skateboarding was more than just an act that inspired me, it was the artwork, the composition of photos, the color schemes of layouts. I think over time they saw that skateboarding lit a fire underneath me to do a lot of stuff, including even getting into college.

KB: One feels this impulse—helping your parents see across this gulf—operating throughout the book. It’s clear that you want readers to leave Chipped with a richer understanding than whatever they bring to it. For many years, skateboarders had no interest in helping non-skaters understand what we do. I’m thinking of Pepe Martinez: “Fuck all you idiots who don’t understand how we talk.” Can you say a bit about what you want readers to understand, and why?

JV: To your point, I think all my life as a skateboarder I’ve been having to instruct people about why this toy is important and why it’s not a destructive force in my life. Then again, unlike those of Pepe Martinez’s generation, I never got nearly the amount of shit for being a skater in 1996 Southern California versus 1992 Washington DC. Regarding Pepe’s quote, it’s not like the middle finger isn’t being flipped in Chipped, it’s just articulating how it needs to be employed. Cops with gang tattoos? Racists? Cabaret laws? They’re all told to go to hell.

With Chipped, I hope readers—skaters and non-skaters alike—get a wider view of skateboarding’s impact. Through reflecting on very specific skateboarding and cultural moments, I really wanted to show what connections skateboarding evokes for me and to encourage folks to explore the worlds that mean something to them, too.

It’s fun to make connections through skateboarding with people who don’t skate. I enjoy finding those moments of empathy in real life. Chipped is this challenge of articulating on the page how non-skate things have impacted my skating; it’s also me challenging myself to explore that direction of the two-way street between culture at large and skateboarding’s culture.

Skateboarding has never lived in isolation. I want skaters to realize their joy and their anger exists in conversation with others who do or do not use our built environment creatively, but who absolutely utilize it to exist.

Kyle Beachy is the author of The Most Fun Thing: Dispatches from a Skateboard Life, named a best book of 2021 by NPR and others, and a novel, The Slide. He lives in New Mexico.

More Interviews