Savagery Belongs to the Real World: An Interview with Gabino Iglesias

Interviews

By Ross Nervig

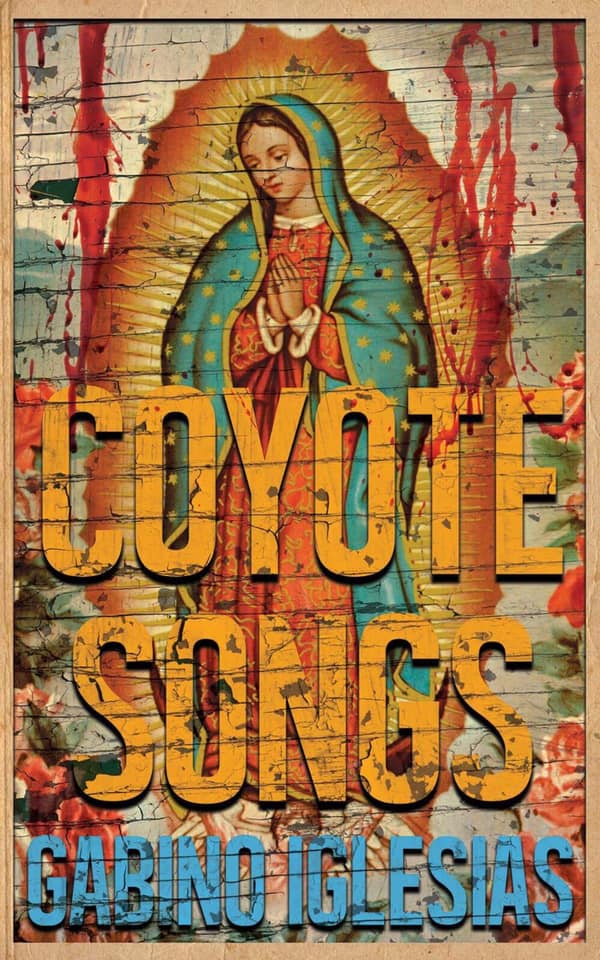

Just read the back cover of Coyote Songs: “Ghosts and old gods guide the hands of those caught up in a violent struggle … A woman offers colonizer blood to the Mother of Chaos … A boy joins corpse destroyers to seek vengeance …”

Gabino Iglesias does not fuck around.

Coyote Songs is a book about borders. The border between the U.S. and Mexico but also the border between life and the afterlife. A little boy watches life leave his father in the first chapter, sending him on a quest into an ugly reality peopled by the dead. A curandera departs her corporeal body and builds like a storm of rage over la frontera. A young widow has a demonic presence growing in her belly where a baby should be. An artist plots a performance piece with a dire outcome.

Iglesias writes in a genre known as barrio noir—a term he coined. For the uninitiated, the author himself explains it best. “I had this idea in my head,” Iglesias said in an interview with Book Riot earlier this month. “Pulp walks into a bar and smashes a bottle in the face of literary fiction while reciting poetry.”

The book is also part of the first wave of novels that directly address the Trump presidency. And on this count, it howls. In Coyote Songs, the reader encounters immigrants fleeing violence in their home country only to be met with other forms of terror as they seek asylum, caught in a zone that is lurid, liminal, and teeming with bad operators. But to read this novel is also to see the boundless power of love as it conquers shitty politics; the thick, insidious mud of racism; and the flimsy veil of death that separates us from our loved ones.

Iglesias took time from his busy schedule as a writer, journalist, educator, and book reviewer to chat with SwR about his new book, justice and injustice, depictions of violence, and the soul-scarring act of writing about loss.

NERVIG: Seething anger is a theme in this novel. How much of your own anger fed into the creation of Coyote Songs? Injustices and cruelties and desperate measures are all catalogued. Was outrage a propellant for the creation of this novel?

IGLESIAS: Outrage is a reaction, so I’d say my anger was the propellant. I’m almost always angry at a variety of things. That’s why I try my best to stay positive, to do things I love. I don’t react to things immediately. I like to read, do research, talk to people. Once you know a bad situation profoundly, your anger becomes an ember. Quick reactions, outrage: those fizzle out. Informed, righteous anger sticks around. I let it drive some of my work. Punching people is illegal, so writing is, among a plethora of other things, therapeutic for me. The mess at the border can be solved, but no one is talking to the right people, and half of the country is siding with a racist. Yeah, I don’t think my anger and things like racism, sexism, and homophobia will vanish any time soon, so I guess there are many more books coming.

NERVIG: The world of Coyote Songs is astonishingly savage. Is it our world or a world of heightened savagery?

IGLESIAS: There is a supernatural element at play in Coyote Songs, but the savagery belongs to the real world. Families left to suffocate in the back of a trailer? Real life. Child abuse? Real life. Violence at the border? Real life. There is a monster in the narrative that devours babies in their cribs. I obviously made that up; however, the stewmaker is based on people like Santiago Meza Lopez, who dissolved bodies for the Sinaloa Cartel. We are used to murder and crime, but on a different level. We don’t get massive communal graves. We don’t get decapitated bodies on the streets or bodies hanging from highway overpasses. Savagery, however, is out there. It’s an everyday reality for folks in places like El Salvador, Colombia, and Nigeria. I wrote about it in a way that hopefully gets folks to understand what some of those crossing the border are trying to leave behind.

NERVIG: You have a character named Alma. Her name means “soul” in Spanish. In some ways she is the mouthpiece for all artists struggling to make a living doing what they love. This desire curdles within her, though. (Which might be a symptom of the pressures of social media.) It led me to wonder: Which character do you most identify with in this ensemble? You are notorious in some circles for your prolific output and your superhuman hustle. How do you keep the despondency or feelings of futility that Alma feels at bay when creating?

IGLESIAS: I identified with Alma and the coyote the most. Alma because creating on the periphery of fortune and fame is always a struggle. You have to make time when there is not space for it. I have two jobs. I’ve faced eviction twice in the last half-decade. I made $930 a month as a teaching assistant at UT Austin. Then I left school and ended up being uninsured for almost five years. The struggle is real. Creating within that framework is at once the easiest and the hardest thing to do. I add to that the fact that I write in a language that is not my native language. You get the point. That said, creating authentic fiction is easy when you come from, and have stayed at, the bottom. In the case of the coyote, he’s an extremely flawed person, but he’s trying to do the right thing. If we’re honest, we are all deeply flawed, and hopefully most of us are trying to do the right thing and help others. You can have a code of ethics that isn’t always tied to that which you’d expect from a law-abiding citizen. My moral compass is unique, and I think so is the coyote’s.

NERVIG: Justice through retribution is another theme in this novel. I wonder if it’s ever that simple? Does violence ever not beget more violence? Does this law of cause and effect exist in barrio noir? Can violence ever really purify?

IGLESIAS: It’s never simple. And you’re right: violence always begets violence; however, sometimes there is no option. Cut the rattler’s head off or get bit, you feel me? Stomp a racist man who’s threatening you. Defend those who are smaller or weaker than you. Destroy all bullies. Hunter S. Thompson said: “I hate to advocate drugs, alcohol, violence, or insanity to anyone, but they’ve always worked for me.” Well, I hate to advocate violence and revenge, but they’ve always worked for me. I was six or seven years old when I broke someone’s arm for the first time. A kid a year older than me was urinating on a girl named Taiz who had Down syndrome. My mom made me write him a card and apologize. I still hold a grudge about that and bring it up from time to time just to mess with her. Abuse people, get punished. Does it work for everyone? No. Is it the best solution? I’m not smart enough to provide a philosophically accurate response to that. Does violence purify? I’ve never felt purified after violence, but I also haven’t felt purified in its absence. The former at least helps me sleep better at night. So, does it work for me in life and in fiction? Always. Your mileage may vary.

NERVIG: Early in Coyote Songs, a coyote beats two young boys so that it will appear they’ve been attacked by gang members and are seeking asylum in the U.S. Their cuts and bruises are meant to play on the sympathies of border-patrol agents. Writing that scene, did you ever worry that someone with anti-immigration leanings might point to it and say, “See, they are trying to pull one over on us”? How would you respond?

IGLESIAS: I don’t worry about that because anyone in this country who is anti-immigration (and isn’t a Native American) is already wrong. Furthermore, anti-immigration folks will use everything as an excuse … and then turn around and celebrate their French/German/Irish/Polish/whatever heritage. I worked with an immigration lawyer for a while, trying to get people visas. That this country denies asylum to children is already messed up. They are running away from violence and poverty. Coming here isn’t a vacation. That’s what anti-immigration people think. You leave everything you have, know, and love behind and set out on that trip because it’s something you need to do, not something you want to do. It’s survival, not pleasure or adventure. What I was trying to say with that chapter is this: a person will be allowed to remain in this country if their face reflects the problems they face in life. If they have the same problems but can’t show/communicate them properly, they don’t get to stay. That is ridiculous. I wish it weren’t so.

NERVIG: Your novel is broken into interweaving fractals. You’ve called it a “mosaic” in other interviews. Which chapters were the most fun to write? Which were the hardest? And why?

IGLESIAS: The chapters with the coyote were the most fun to write. He is a bit insane, but his devotion is admirable, and his heart is always in the right place. He also gets to interact with a reformed Nazi in the figure of Padre Frank, which was a very emotional writing exercise for me. Those chapters are fun, violent, and packed with religious zealotry. That is a good mix that more or less offers three of the main elements of barrio noir. The hardest chapters to write were those dealing with Inmaculada, the ghost. Writing about loss is hard. Writing about the loss of a child is harder. Writing about hate comes easy for me. Writing about love is much harder. When love and loss collide, your soul gets scarred. It happens every time. I can write about violence and feel intimidated by the work of folks like Benjamin Whitmer, Jeremy Robert Johnson, and David Joy because they do it so incredibly well. They’re better than I’ll ever be at that, and I’m fine with that; however, when I write about loss, I feel intimidated by my own lack of writing chops, by my inability to put into words the things that live in people’s hearts. I promise I’ll get better at it.

Ross Nervig is a writer living in Nova Scotia. From 2012-2017, he served as a founding member of Revolver—a literary arts collective based in St. Paul, Minnesota. His work has appeared in Kenyon Review, Bluestem Journal, Bayou Magazine, Southwest Review, and Huffington Post. He is currently an MFA Candidate in Fiction at the University of New Orleans. In 2018, he received the University of New Orleans Creative Writing Workshop’s Ernest and Shirley Svenson Award for Fiction.

More Interviews