School Night

Web Exclusives

By Mary Marge Locker

I was down on my knees, and Deb was wriggling my tooth. There was a loud CLATTER! from the garage, and we both turned suddenly toward it, like maybe we could see through the yellow kitchen walls and find out what was happening.

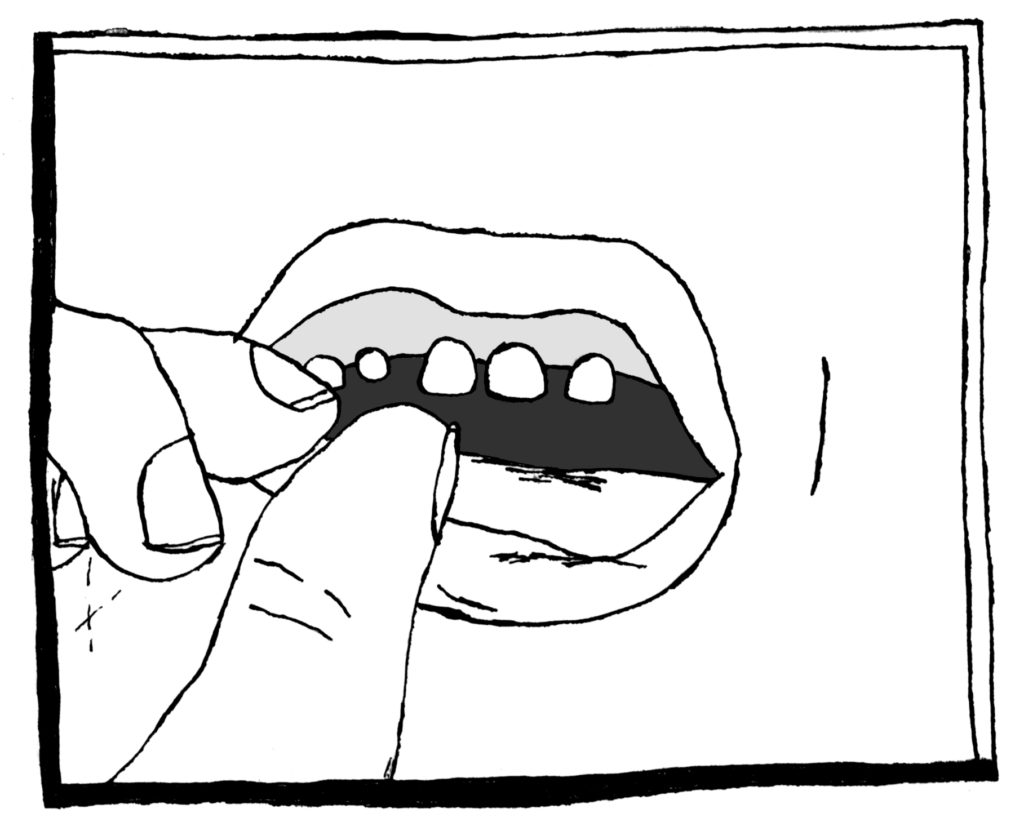

I figured raccoons and faced back up at Deb. Her fingers were still on my fourth bottom tooth on the left. It was the last baby tooth I had, and nobody else at school had any. I’d been bugging her about it since my parents left at 6:30 for the fundraiser, and she finally said why not. But Deb was looking the other way.

“Juth do it, Deb!” I called as best as I could. Her fingers were busy and wrong in my mouth. She looked down at me, her eyes all big or maybe it was the angle, and she ripped hard and I said “Aggh!” but it didn’t hurt that much. I could taste blood in the gutters around my tongue. She was right: it hadn’t been ready to pull yet.

“Crap,” she said. “Let’s get you some cotton balls or something.”

I pushed up off the tile floor and sat down on the countertop while she went looking. I faced the fridge. There were my spelling tests, lists of words like application and recession and coward in a short column, and next to that a picture I had drawn in my Creative Process Survey of me and some dogs, Jack Russell terriers and a big fat Chinese shar-pei, which I knew about because of the New Revised Encyclopedia of Dog Breeds, which I had instead of a pet because of all of my dad’s sad allergies.

There was another CLATTER! CLATTER! in the garage, and I called out, “Do you think my bike is ok in there?”

The pizza box was still on the table. I wondered if Deb would make me take out the trash. The pepperoni grease would smell funky if we left it there overnight. Usually when Deb came to babysit, my mom had leftovers in the fridge for us. But the fundraiser had been months in the making! And trash was one of my chores.

I heard something fall in the bathroom. I imagined a stampede of all kinds of little furry critters had invaded. A couple vermin might get stuck inside and have to become our pets.

Deb was suddenly beside me and lifted me off the counter, and I laughed, and she said, “Be quiet.” I was in her arms like a baby, even though I weighed as much as any fourth grader. She took me into the bathroom and set me in the sink. She fumbled with the gold knob of the door.

“Hey—” I said. It wasn’t very comfortable.

“Listen to me right now, Joanie. Stop talking.”

Then I got scared. I felt like I was going to have diarrhea right there in the sink. It hadn’t occurred to me that anything bad could happen in my house, in a place where my mom and dad or Deb was always staying up until after I fell asleep.

“We are going to be calm and quiet.” She took a deep breath between each sentence, like following doctor’s orders. “I think there is someone in the garage. This lock isn’t working.” There actually wasn’t a lock. I had been taught about privacy. “I’m going to call the police.”

“Where’s your phone?” I asked. I might have sounded mad, but I was just scared. I wanted to apologize for it. No one is supposed to be in your garage when you have a security system. If only we’d had a guard dog. Maybe we’d have to stay in here forever. Live on the cough drops in the medicine cabinet.

Deb’s face fell. She looked down at her hands. In one was a pile of cotton balls. In the other was my fourth bottom tooth.

“The door to the garage is locked, right?”

My mouth fell open about halfway. I had no idea. We hadn’t gone outside since my parents left. I wondered if they were having fun at the fundraiser. They had been all dressed up and smiling. Sometimes they locked it and sometimes not.

“I’ll go get my phone,” she said. “Stay put.”

I was proud of my parents for picking Deb to be my babysitter. She had taken a few times to get to know—she was fifteen, a nail biter, and wore the same pair of stretchy track pants every time she babysat, as if we were going to be doing gymnastics. Some of the really cool high school girls babysat my friends, and Deb definitely wasn’t cool. She had a mole on her nose that always distracted from the rest of her, but it didn’t really mean she was ugly. And she was on the academic quiz bowl team. But we got along good, and she watched movies with interest and never laughed or condescended when I said hey maybe we could get out my old paper dolls.

She gave me a pat on the shoulder and clicked open the door.

When Deb opened the door and there was a man standing outside of it, neither of us made a noise, or jumped, or cried.

He had a black scarf tied around the bottom half of his head, and a beanie on. I thought he was probably blonde. He said, “Come on out.” I guessed we didn’t get to make a decision. He narrowed his eyes at me, focused hard like to decide what he’d do with me, and Deb kind of croaked like she was going to say something, but he leaned over and grabbed my chin before she could. His hold was tense.

“Why the fuck are you bleeding?” he asked me, and in all the CLATTER, I’d forgotten that I was. I forgot about the tooth, and for a minute thought he’d already hurt me. I was already his garbage, his wreck. He jerked my head sideways and then looked at Deb. He had not accounted for something that was happening. Maybe she had hit me, maybe we seemed super tough. Deb, I wanted to ask, what do we tell him?

He made us walk back into the kitchen. He pulled out the chairs and flipped his hands upwards, like to say, Have a seat, ladies, but not in a nice way. We sat down. I wanted a cue from Deb.

He knelt and tied our hands to the chair backs with plastic zip ties. If we hadn’t been here, what would he have done with those? He didn’t put any tape on our mouths or anything, and my feet were free to kick at him, but they didn’t. He left us there and walked down the hall.

“Why didn’t we just go out the front door?” Deb grunted.

The front door. I hadn’t thought of it. It was on the opposite side of the kitchen, and it led to the lighted pathway to the street. He’d been in the garage. And we had hidden. I felt the tingles in the kitchen with us, the same way I used to when I scared myself for no reason. His footsteps on the tile were soft, but they bounced an electricity back to us. I wondered if Deb felt it, too. Like a stampede in the hallway, reverberating across half the house. I thought about the stampede I’d dreamed up, all squirrels and rabbits and groundhogs among them, and that idea felt like years ago, a different me.

Deb’s phone was on the table by the pizza box, and it vibrated. She was taking short hiccupy breaths.

“We are going to be fine, Joanie,” she said a couple of different times. I nodded. My wrists hurt angled back around the chair like that.

The man ducked his head around a hallway corner like to check that we were still there. Deb didn’t drive, so he probably thought nobody was home. Guard dogs. Doberman Pinschers. That’s all we needed.

There were some speckles of blood on the tile from after my tooth came out.

He went into my parents’ room and shut the door.

“What do we do?” I asked. “Should we scream? Maybe Mr. Kesterson will hear us?”

He was going to come back to us in all that black he wore like an animal, and we were not prepared. It sent prickles through me, from my fingers down to that place below my stomach where all the bad feelings were always zinging.

Deb shook her head and cooed soft things at me. “He will leave soon, and then we will just wait on your parents.”

“He’s a thief? Not a murderer? He’s not going to kill us, you don’t think?” I couldn’t control all the fast words coming out of my mouth. I thought about my bedroom, all the way upstairs, how my paper dolls and my stuffed animals were safe there and still would be later, no matter what happened. He hadn’t come for any of that.

“Stay calm,” Deb said. It was like now that he had bent so close to us, Deb was no longer afraid. She seemed faintly drugged, somehow comfortable. There was something anticipatory in her pose.

He came back out of my parents’ bedroom and walked over. His eyes darted like he was making it up as he went. He opened a fancy red knife. I cringed and started huffing, trying to think what I could say to prevent this. How much I loved all those things in my room. What else? I was ten. Did I have to deserve my life?

I opened my eyes. He slashed Deb’s ties and then mine. We might have been stuck there four minutes.

He stood us up, held Deb under her arm, and grumbled at me.

“You have to go back in the bathroom. I changed my mind. You’re going to stay in there.” I almost nodded, did the calm and right thing that Deb would have suggested, but suddenly I felt hot in my wrists and my ankles and a deep feeling of ownership arose for my house.

“TAE KWON DO!” I was prepared to shout, but it came out weird, a whisper, a croak. I couldn’t think of what Tae Kwon Do moves would look like, though, so I did my best to strike a menacing pose. Arms weakly above my head, hands clenched like I was holding sheriff’s badges.

But the man just shook his head at me and pointed back to the chairs in the kitchen.

“Please cooperate,” he said.

I hung my head and obliged him. What else was I supposed to do? Deb faced the opposite direction, looking toward the bedroom, which was lit. He had turned on the lamp by the bed, the one that always let me know Mom or Dad was still awake when I came downstairs. I had to do something. Deb was going to die, maybe, and all because she’d come here to babysit. Well, more because she’d forgotten to bring her phone to the bathroom, and even more because we’d forgotten we could just go out the front door.

“I won’t cause a problem,” I called. “If you promise you won’t kill us!”

He frowned at me. I couldn’t see his mouth under the scarf, but his eyes looked like he frowned at me. “No,” he said. He rearranged his handhold on Deb. “I’m not going to kill you.”

“Just stay put, Joanie,” Deb said. She was staring off at my parents’ bedroom.

He came back to me and pulled out another zip tie. He had changed his mind again. This time he hooked it around the refrigerator door and pulled it tight so I could barely feel my wrists. If I pulled against it, which I did as he closed the bedroom door behind them, the refrigerator door opened, and I had to walk in a semicircle and then walk backward to shut it. I could smell our leftover pizza slices. Ached momentarily for a glass of cold milk.

What were they doing in there, I wondered. I imagined Deb trying on all my mom’s clothes. Sitting at her vanity, fingering her makeup brushes like sometimes I did. I swung left, opening the refrigerator again. It hummed. I couldn’t hear the man or Deb. I wondered if my parents would be home soon. My dad could go kill the man in his bedroom, pull whatever he’d stolen out of his bag and put it back in all our proper places. My mom would grab a kitchen knife and whoosh, I would be free.

The icemaker tumbled on in the freezer. For a moment it sounded like a CLATTER, and I thought it was all happening again.

How was he going to kill Deb? I’d hear a gun. So would Mr. Kesterson next door. The shiny knife was small, but I guessed all knives worked the same. I couldn’t even think of any other ways that somebody else might make you die. I measured the minutes in tightly paced semicircles, opening and shutting the fridge. The lamp was still on in the bedroom. My belly clenched fist-tight.

He was not killing Deb. I wanted the not-killing of her to be over.

After fifty-three semicircles he left the bedroom, shut the door with a nudge, and walked out through the garage. He didn’t even look over at me or wonder if I was still there. I almost screamed at him that he hadn’t killed me, but that probably wasn’t a good idea. A horn honked somewhere down the street.

“DEB!” I yelled. I yelled it so loud and so many times that it turned into more of a cough than a word, and before I knew it, I was crying, because he had lied to me, she was dead. She was like my sister and my friend, and somehow I knew I had killed her. The electric, heavy feeling hung in the house. It had come off of him and stayed behind.

I walked backwards until the refrigerator closed. The hum helped calm me down. I took deep breaths like Deb had done at the beginning of it. Then she came out of the bedroom. She looked pretty much ok.

She came and sat on the floor next to me.

I felt stupid for crying if she wasn’t.

“Can you get your phone now?” I asked, sniffling.

“I just want to wait a minute,” she said. She stared hard at the tile—I wondered if she had seen the specks of my blood.

“What happened?” I asked. I didn’t demand she untie me, but my arms were really hurting at this point. I tried not to seem so pathetic. “What did he take?” I asked. I thought about my mom’s jewelry drawer. My dad’s watches. I would have noticed if he had left with their TV.

“The man—he—” I began again.

She croaked a half-laugh. “Boy,” she said. “He was a boy.”

“What are you talking about?” I sniffled some more.

“He had on basketball socks.”

There was a moment, or an almost-moment, where it seemed like Deb might smile. Instead, she blinked hard a few times and kept on staring at the floor.

“Socks?” I asked. I was embarrassed. No boy would break in and scare us like that. If he’d been a kid like us, our own kind, he would have felt some allegiance. And she didn’t respond, so I said, “Deb, please cut me off the refrigerator.”

She did it. I ran to the phone and dialed 911.

Deb sat back down, cross-legged on the floor, between a spatter of blood from my mouth and the two halves of a sliced zip tie. She shook her head in disbelief. I told them the address of my emergency, and then they asked what it was.

“I don’t know,” I said. “Somebody broke in. He tied us up.”

The dispatcher had a faint accent, and I imagined she had grown up being rocked in a hammock, her front yard the sand of a beach. “Keep talking to me, sweetie,” she said. “Tell me what else happened.” But I couldn’t think of anything else, because nobody was telling me anything, and so I just kept saying that I was in pain, because I was, my wrists hurt, and so when the ambulance showed up, they circled me, to help me, and not Deb. They saw the dried blood around my mouth. My parents had arrived first, and they were mildly drunk, it seemed, but they both cried and then I cried more. They held me close, and my dad put three hundred dollars in Deb’s hand. She would have refused it, I think, any other night. They knew I was not the one who had been hurt. We talked to a pretty lady police officer with soft hands that patted ours, and then Deb talked to her in private.

Deb walked home soon after, with an officer in a gray set of slacks. I think my dad would’ve driven her, but I don’t think he was supposed to be driving. Before she left, she touched the pocket of her track pants and made sure the three hundred dollars were still there. Then she made sure I had my tooth, that it hadn’t been lost in the excitement. She put it in my hand, smiled, and hugged me.

That was her word, the excitement.

![]()

There was a boy in my class named Fletcher Adams. He knew all the nitty-gritty as the other boys called it. When one of them picked up the tampon that fell out of Angelica Turney’s backpack, they took it to Fletcher, and he explained. I asked my friend Leon to recount the explanation to me, and he laughed.

But Fletcher always knew the neat-deets, too. In second grade he told me and Alise and Ella and Isabelle and Emma Kate how we had each been made. In our moms’ stomachs, sure, we had always known that, and yeah, we knew something about dads’ putting us there in the first place, but he took the longest fingers on each of his hands and did a demonstration. Alise went home sick later that day, and I felt sorry for her. I could handle the truth.

But that night after he told us, before bed when Mom and Dad came upstairs and gave me and Charlie and Burt, my stuffed-animal golden retrievers, our goodnight hugs and kisses, I got a bad feeling down in the deep heart of my belly. Mom asked me, “Joanie-bug, do you feel ok?”

And then I started crying. I cried like a little baby. I felt like I should take a couple more showers before I got in these nice clean green sheets that Mom had washed for me. Mom and Dad sat on both sides of me, and they were patting my back and giving me little kisses and asking what had happened, what was wrong. I just shook my head. I loved their little kisses on my wet hair, but it made me feel dirty now, because I was wondering about how they kissed each other downstairs in their own bed at night, and if that was what had led to me. I told them I was sad because I had seen some tiny stray black dogs on the side of the road and I was worried about them because it was cold outside. I felt bad for lying, but what can you do. Dad tucked my head under his chin and said softly that everything would be ok and he bet their owner had found them. Mom hugged both of us as best she could, and she told me what a big heart I had. They smiled and held me until I stopped crying, even though I felt dirty, unworthy of that love. I tucked Charlie and Burt under my arms, and I eventually fell asleep, dreaming of a row of flying babies coming in and out the open windows of our house. I had always liked babies, but suddenly they were something brand-new. I felt confused and ashamed but also like I’d known it all along. How a dog might feel seeing his tongue reflected on a bright day in a bowl of water. Scared! Part of everything, but something I’d never even known was there! But hey, do dogs even feel, you have to wonder.

Mary Marge Locker grew up in Alabama and lives in New York.

Illustration: Josh Burwell is an artist and illustrator from Mississippi currently living and working in Los Angeles, California. You can find more of his work at jburwell.com or on Instagram @jburwell.

More Web Exclusives