Seeking Freefall | An Interview with Lindsay Lerman

Interviews

By Nate Lippens

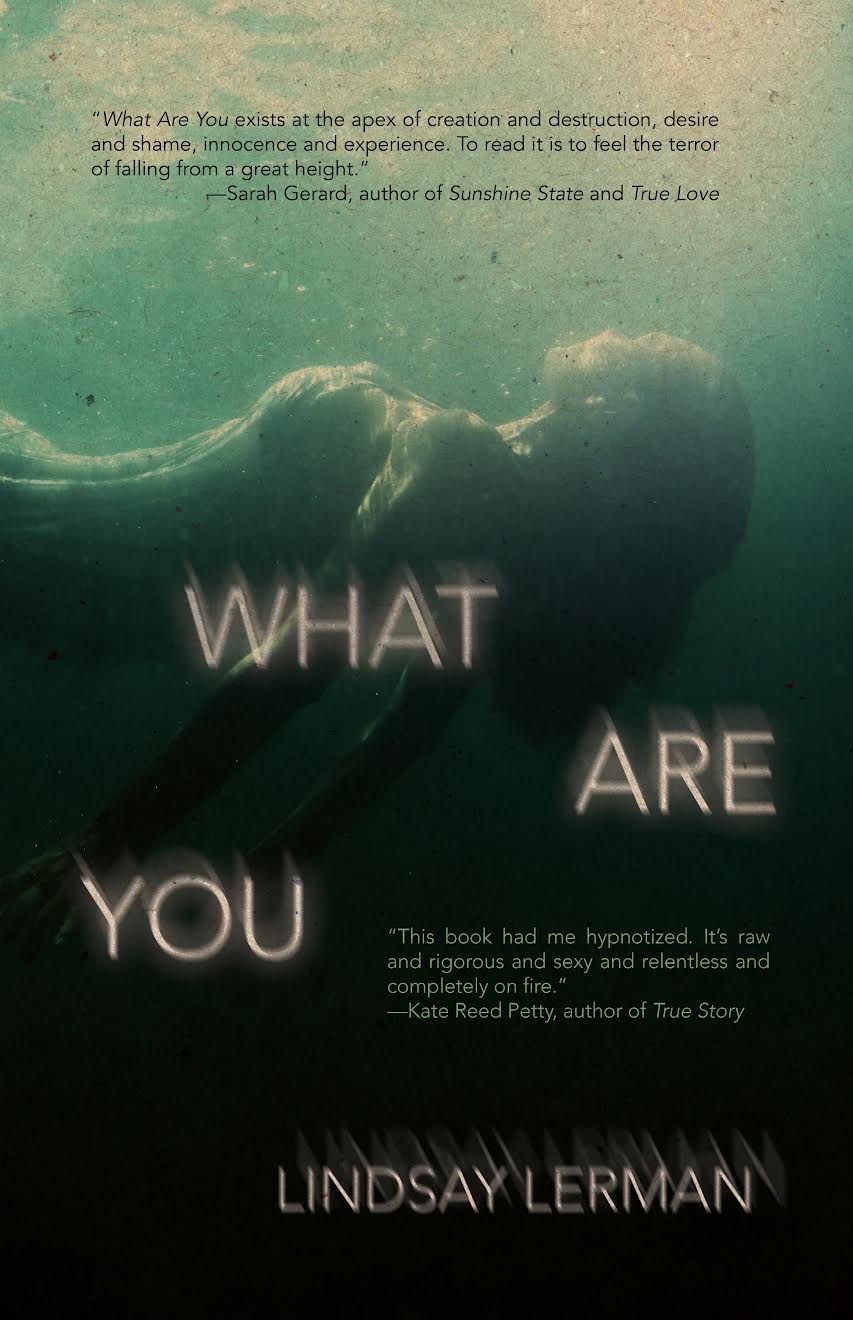

Lindsay Lerman’s What Are You (Clash Books) doesn’t flout conventions so much as it creates a completely different code—one that switches constantly. In the novel, an unnamed woman moves through a series of scene-slash-memories about love and hate, birth and death, connection and alienation. Each of these states is fleeting, yet the strength of the woman’s seeking (for life, understanding, better confusions) pulses along to a human heartbeat.

Although What Are You’s protagonist insists she isn’t a narrator, her statements of renunciation are also completely authoritative: “I understand that you’ll be tempted to think of me as your narrator, but I don’t recommend it”; and “I write to you as no one in particular. I need a new language. Please try to understand.” She is determined to acknowledge how unsettled she is, how unsettled we all are, in our thoughts and our bodies.

These efforts began with Lerman’s debut, I’m From Nowhere, a book that reckons with grief and personhood. What Are You has that same questing energy. The discoveries here are radiant, and helpless—what Clarice Lispector (in Aqua Viva) called “diabolic joy.” Readers can expect to encounter elated sadness, tethered freedom, and a search that only wants more mystery. The book could be a kind of abstract blues, but, again and again, the narration deploys specifics and scenes to nail down fleeting moments of love, only to let them go.

Lindsay and I swapped manuscripts last year and landed on the idea of a conversation. However, one interview couldn’t contain it all. After talking with her about my novel My Dead Book, I was thrilled to get her into her thoughts about her rich, strange, and brilliant book.

Nate Lippens: I kept thinking of What Are You as a page-turning mystery, but with each page the mystery begins anew. Testimony, evidence-gathering, and fragments are mentioned. A kind of case is being built, argued, and dismantled in the book. There is such rich back-and-forth about who is speaking, who is being spoken to, and who is being spoken for: “you” as many, “you” as singular, “you” as you. But the slipperiness of the second-person never seems evasive. There’s a perfect pressure exercised with each shift. How much of that was intuitive, or subconscious, and how much of it was planned? Or is even trying to quantify that movement or name it as any kind of process possible?

Lindsay Lerman: I think the heart of this book is a psychotic attempt to communicate with the forces—the eternal forces that shape all of us and everything we produce and create. But how can we possibly communicate with those forces? How could we consider the attempt a success or a failure? I found myself in a place where it seemed there were no metrics. I understood I would have to create my own, and that’s a dangerous thing to do. It risks madness. But I don’t want to glamorize or fetishize madness. With this book, I wanted a new language and a new kind of communication. So I attempted it, accepting that evidence of its “success” might also be evidence of its “failure.” I remained suspicious of myself throughout. The slipperiness regarding narration, structure, and genre was entirely intuitive and unconscious at first; it was simply the only way to do it. Then, later on, I made a more conscious decision to go with it. I needed to. I don’t look at the world and see abundant evidence of very clear, fully-formed, hermetically-sealed subjects and objects. (To begin with, for example, the “I” who began writing the book five years ago is not the same “I” who finished it.) I look at the world and I see a massive root ball of interconnection and cross-contamination, and I am interested in art that takes that as a starting point. I want my books to be promiscuous in this sense. Curious. Searching. Going. Desire threatens the social order, after all.

Some of the more pseudo-academic, philosophical moments in the book were originally parts of essays I had written. (For a while I thought I was writing a book of essays.) But once I understood I was doing something much harder to categorize, I took those essays apart, found the beating heart inside some of them, and wove them into this narrative wherever they seemed to fit. I now know they were never meant to stand alone as essays, and that it would be unfair and dishonest to try to do that to them now. But I didn’t know that for a while. This book taught me so much, but it especially taught me that when you create in forms you don’t recognize, you can also live in forms you don’t recognize. Living and creating are always interlinked. There is a small but very significant freedom in that linkage.

That said, I don’t think there’s really anything “new” about my approach in this book. To me, it behaves like an album. We’re accustomed to music that experiments and plays, even when it’s relatively standard, or not obviously “experimental.” Over the course of one album, narration will shift, tone will shift. The second act of the album might drag, but then the third act or concluding movement hits so hard it makes the necessity of the long second act clear. There are just so many possibilities in that form. I got as wild as I could let myself get, knowing that my discipline would eventually require me to make it all come together—to find temporary cohesion.

NL: The musical approach makes a lot of sense: riffs and solos and structure. And Joni Mitchell makes a glancing appearance early in the book—“‘Like the church, like a cop, like a mother, you want me to be truthful,’ but Joni knew: then you turn it on me like a weapon.” Music, movies, and art are part of my everyday. I know they inform what I do as much as books. How much do other art forms influence or become atmosphere in your writing?

LL: I let art possess me and my life. I let it influence the atmosphere of my life. Then, in time, it influences my writing. Whatever I absorb makes me more free; it’s my responsibility to spread that freedom if I can. It’s outside the boom and bust of capitalism, the obsessive accounting and ranking of bourgeois mental structures. That’s the gift of art, before it enters the marketplace and even sometimes after. I believe in the possibility of the gift.

NL: For me, What Are You belongs to a lineage that includes Anne Carson’s Decreation and Clarice Lispector’s Aqua Viva. Where Lispector’s narration is a metaphysician, however, your narrator’s questions are rooted in memories—flickers and glimmers, really—of grotty yearning, sex, and tests of mental and physical strength. Her abstract ideas are grounded in experience. Is this central to your writing and your philosophy (a philosophy of writing/a writing of philosophy)?

LL: I think that’s almost an ethical code I followed while writing this book. I refused to separate ideas from matter, whether that matter is human bodies or trees or bacteria. This even plays out in one of the elements of the book that’s hard to describe—when the narrator wonders throughout if some invisible but palpable forces in the universe are literally penetrating her, fucking her. It was all a refusal, on my part, of the fiction that everything isn’t playing itself out on us, in us: the matter that we are.

The tension between whatever we call “mind” and whatever we mean by “body” has always been a productive—even seductive—tension for me. I can’t conceive of a neat separation between the two. Every philosopher, poet, musician, and sociologist whose work I engage with in this book has something to say about it. In turn, I have something to say about what they say.

I still remember a moment in the first philosophy class I ever took, Philosophy 100 with Peter Kosso at Northern Arizona University. Kosso was breaking down Descartes’s famous cogito ergo sum argument (the “I think, therefore I am” one), and I stayed after class to ask a question. I was seventeen, and this was my introduction to analyzing an argument. I felt myself kind of light up as I said to Kosso, “I’m so confused—how is it that his own bodily experience is really not enough for him to be convinced of the fact of his existence?” And Kosso gave me this look that I now interpret as really meaningful encouragement, a look of “you might be in it for the long haul—you seem to be actually thinking about this.” The difference is that, for the past decade, I’ve stopped thinking about it from within the confines of academia (not that I was ever securely “inside” academia, even as a serious doctoral student), and I’ve let philosophy do what it’s always been meant to do. I come to it with questions, with concerns, with a deep need to understand, and I humble myself before this conversation between thousands and thousands of minds from around the world and throughout all of human history. (So it is never really just “philosophy” I end up digging around in). That’s how I always find a place to start—I find what I need to make it possible for me to keep asking questions. My thinking, writing, and feeling begin there, and they develop together.

NL: What Are You is a serious book taking in huge shifts of thought and memory. Still, the book also contains a lot of play: formally (structurally), but also just on the line level. You ask a lot of the reader but you’re also giving a lot back. The pleasure is there—like a great turn of phrase that frisks the whole paragraph it’s in—but some discomfort too. Nothing simply has one meaning. How did you find that balance?

LL: With this book, I took an axe to myself in many ways. I was broken, but in a good way, forcing myself to find what was worth keeping and cultivating, letting everything else go. That’s the sense of balance I sought—balance in the sense of equilibrium maintained by tension. The book mirrors that, performs that. At some point it became an “everything” book. I realized it was not going to have a single theme, or be organized around a single event, or even fit into one genre. I gave myself over to the way every line and paragraph has multiple meanings, multiple readings. At first I was scared of this (“what will they think?” etc.), but then I understood that maybe this is how it’s a “philosophical” book. To me, something is a work of philosophy if it has the capacity for elaboration and interpretation—if I can feel that it’s not driven by a sense of needing to have the final word. Feuerbach calls it Entwicklungsfähigkeit (literally “capacity to be developed”). Salomé (and many in her footsteps) would call it the erotic. There are a thousand ways to describe it: mystery, the remainder, possibly even the sacred. With this book, I learned just how joyful and beautiful it can be to stay in that zone for a long time. There’s difficulty and struggle—it’s not always easy—but there’s also something cool and sexy and subversive about the give and take that can occur there. This is connected to my use of that Joni Mitchell quote as well. I can’t pretend to offer the absolute truth, with no alternative readings, no things left unsaid Besides, when you try to do that, people often just want to punish you for it.

NL: There was a comment on Twitter about fiction being read as autobiographical and you said, “What if—hypothetically speaking—a woman writing her second book decided to write in first-person as a kind of taunt, due to how many people assumed her first novel was autobiographical, and what if she addressed everything in the book to you (maybe the reader?), implicating everyone.” How aware are you of readers’ perceptions when you’re writing?

LL: I try to be lightly but warmly attentive to reader perception. I write because I strive to communicate. It does me no good to pretend otherwise, but I have to be careful about letting potential readers in too much. I realized something important after the publication of my first book. I had spent much of my life cultivating relationships with people I respect and take very seriously, so I’ve always had relationships in which opinions about me are offered by people who know me well and are invested in my flourishing, just as I’m invested in them and their flourishing. The opinions flow relatively freely between us because there’s mutual trust and kindness and love and all that amazing shit present in good relationships. But things changed after I’m From Nowhere came out. People I’ve never known (and will probably never know) had things to say about my intellect, my body, my ambitions. Don’t get me wrong; much of it was very positive and empowering. It changes you when an artist you’ve respected for your entire life reaches out and says really nice things. But you can’t let it change you too much, or it can fuck up your ability to keep having those relationships of mutual investment, where assessments are coming from a place of (mutual) understanding. So I’ve had to recalibrate my relationship to relationships, even with potential readers.

As far as that taunt regarding autobiography: there were definitely some moments while I was writing What You Are when I thought, “OK fine, if you’re going to insist that I am every character I create who might have any passing resemblance to me, I’ll give you someone who cannot be pinned down, someone who covers her tracks because the hunter in her sees the hunter in you and knows what you’re up to. Then you can come to whatever conclusions you want. It’s not my business anymore.”

NL: I remember reading a comment from you in which you called your first book a pocket knife and your second book a river. And, as I was reading What Are You, this passage stuck out to me: “If I’ve lost my liquid nature, I need to find my way back.” The narrator’s search back is the incredible ebb and flow—the accretion and subtraction—of memory. Was there a point when you knew you were writing a river?

LL: There was a point when I knew it was liquid. I wrote many of the sections of the book in a kind of trance, and water kept showing up again and again. In the late winter of 2021, when I was doing a big reshaping and editing of the book, I happened to be at the beach. I love being at the beach in the winter, when it’s empty, the wind is cold and sharp, and you have all that punishing vastness to yourself. I had spent most of the day working on the book, kind of coming to terms with it, asking myself if I was going to make it a proper novel—like a much more standard novel—and wondering if I should take six months or so to just give it a more easily recognizable shape. To be the kind of book that has a better chance of showing up on lists, being eligible for awards, etc. I stood at the edge of the water for an hour, just watching the waves crash and the water receding, over and over again, and I understood it was time to let the book go, to let it be the beast it needed to be. I struck a bargain with myself: let this book be what it needs to be—don’t ask it to be a good girl at the dinner table, and if you think, later on, that you need to write a more standard novel, write a more standard novel. It was like the ocean was shouting at me as I stood there watching it: “Will you let this thing you’ve made be wild and ferocious, or will you be ashamed of its wildness?” It sounds dramatic and overwrought, I know, but in that moment, I understood that I couldn’t live with myself if I forced this book into a prim and proper form. This book did help me remember my liquid nature, and the least I can do is let it have its own liquid nature.

NL: Chapter Forty-Seven of What Are You opens with “What remains?” and then, “I could never understand why everyone else wanted to fill the void—or why they bothered to try. It seemed like such hubris to me. The best I could hope for was not being consumed by it—being able to exist in relation to it—not being sucked in and taken down and snuffed out by it. Could I let it in? Could I offer it residence here? What other choice did I have?” That third choice, that zone, is where the whole book vibrates. The simultaneous knowing and unknowing; a kind of peripheral vision that something else is there. I know there’s no solid answer, but it seems acceptance of this pull between being consumed, consuming, and another thing just out of reach, is the way forward, the way to remain.

LL: It really feels to me that that’s the only way to stay alive. To stay alive alive, you know? I have to look emptiness in the face and stay with it. And not just emptiness, but everything—evil and hatred and beauty and terror and tenderness—everything that strikes us dumb, that interrupts our usual sense-making patterns and habits. I have to continually examine the world and find out if I still desire it. I can’t distract myself for too long with things that seem to temporarily make the world disappear (fill the void, etc.), because I pay a price I don’t want to pay: I feel asleep in life, I stop paying focused attention, I get too slack, I’m less loving and more brittle. And, of course, examining the world means letting it (including the void) into you, and also going deeply into it. We can’t know in advance what comes in and what gets out.

In keeping with the Bataille homages scattered throughout What Are You, there are moments when the book seeks freefall. In life, as in writing, I think the freefall can’t be forced, but a book can give it a little bit of shape—the suggestion of color and contour—so that anyone curious about seeking freefall can feel permitted or maybe encouraged to do it on their own. It’s akin to what Kundera writes about vertigo in The Unbearable Lightness of Being: that it’s not fear of falling that causes vertigo, but the voice of emptiness and the desire we have to fall right into it. It lures us, calls out to us, and we need to be able to encounter it without losing our minds or seizing up with terror simply because the void can’t be tamed or defeated with our usual pathetic methods of establishing dominance. There is no “winning” or “losing” with the void—just as I believe there is no “winning” or “losing” with expression (including the creation of art)—so we must accept that we live with, in relation to. There is no conquering and disposing of the body. And there is also no outrunning. There is only being with.

NL: We’ve spoken before about friendships and loss. What Are You’s dedication reads: “For the fools. And especially for Tim and Aeyn, wherever you are.” I won’t call people I’ve lost spirit guides, but I do feel like memory and my responsibility to it are present when I’m writing, even—and maybe most especially—when I’m not writing directly about the actual people or events, in that third realm between memory and imagination. I get the sense that’s something we share.

LL: Yes, absolutely, Nate. I think of those friends I’ve lost as something like guides. I keep them with me. The places where we meet (in my imagination, in my dreams, maybe in some other realm; I don’t really know) are the domain or the setting of much of What Are You. They’re my fools. I’m their fool. We’re all fools for love together. I have a responsibility to keep alive what they made possible within me. If I can look at something I’ve created and understand that they’d be proud of me, I can live with myself.

Nate Lippens is the author of the novel My Dead Book (Publication Studio, 2021 and Pilot Press London, 2022). His fiction has appeared in the anthologies Little Birds (Filthy Loot, 2021), Responses to Derek Jarman’s Blue (Pilot Press, 2022), and Pathetic Literature, edited by Eileen Myles (Grove, 2022).

Author photo: M. Price

More Interviews