Semiotics for the Global Damned

Reviews

By Conor Hultman

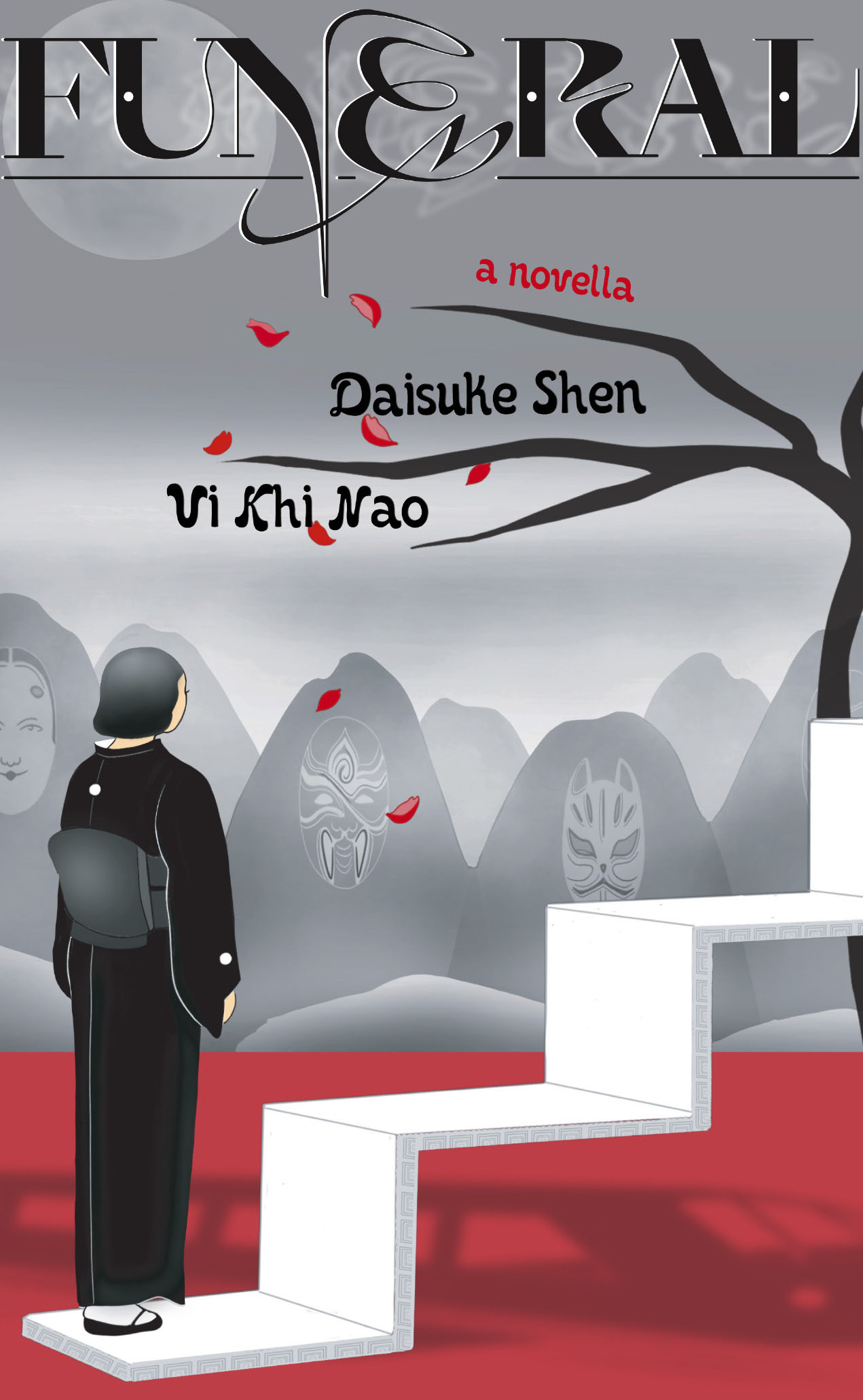

Funeral is a litany of heartbreak, a queer pilgrim’s progress in retrograde, and a Pan-Asian flight through pop culture detritus. It is a pocket Bible for the accursed disguised as a novella. Authors Daisuke Shen and Vi Khi Nao have collaborated to create a genre-blend sure to please piquantly refined palates. It even features multiple endings, one of which might as well serve as the contemporary all hope abandon ye who enter here: “Of reconciliation: there is none.”

Funeral Parade of Roses is a queer Japanese art movie from 1969. It follows Eddie, a trans woman who works at a gay bar in Tokyo, and her knotty associations with friends and lovers. The film is a retelling of Oedipus Rex that collages documentary footage, experimental photography, melodrama, and violence. Nao and Shen’s book picks up from the film’s end—Eddie blinding herself after sleeping with her father, who kills himself upon the discovery—with Eddie in Hell.

What a queer Hell it is. Funeral imagines it as a surreal mirror world, both familiar in its mundanity and uncanny in its Bosch-like visions. People need jobs in Hell, earning Hell bank notes so they can eat and rent apartments. Richard Nixon has an underworld career as a lunch lady; Johnny Depp works as a chiropractor; Eddie is starting Hell’s first boba tea restaurant when the narrative begins. After a breakup, Eddie sets out after her ex, Xing, on an odyssey into the living world. While the sequencing plays like the Odyssey in reverse (remember, Odysseus sees his king, his mother, and doomed mythical heroes like Heracles and Sisyphus on his descent into Hades), the diversity of Funeral’s cameos is much in the same spirit. Eddie’s story is peopled with a bizarre but somehow charming weave of figures: Cathy Park Hong, Machine Gun Kelly, Dolly Parton, George Clooney, to name a few, not to mention Satan. For example:

Morning exercises are led by Bùi Thanh Sơn, who is very proud of his strong, veiny muscles. He constantly flexes them, much to the delight of Sally Rooney and Osamu Dazai. “I could kill him with one hand,” Xing had whispered once, and Eddie elbowed her in the stomach.

Like the film to which it serves as a kind of sequel, Funeral uses an amalgamation of techniques to achieve its artistic aims. Alternating chapters see an infusion of playwriting, photographs, songs, letters, text messages, logic formulas, paintings, doodles, alphabets, signs, guides, translations, moon charts, schedules, and the Chinese Zodiac. These formal unorthodoxies are exciting in their artifice, allowing for a successful marriage of medium and message. Eddie’s afterlife is a story mixing high and low —not to mention Easter and Western—cultural references, and so the book teaches you to read its images as you read its text. Funeral is a new kind of semiotics for the global damned. If that sounds complicated, don’t worry; above all else, the book is fun. It’s also thoroughly unpretentious, and therefore truly worthy of the attention and appreciation often afforded pretension.

The authors alternate chapters, their baton-passing telegraphed by text color (Shen=gray; Nao=black). The best opportunity to compare their styles is in the novella’s dual opening:

Eddie plops her eyeballs back into her skull, turning away from the crowd. She turns to go to the bathroom, ignoring the people watching from outside. She wishes she had drugs. She wishes she had eye drops. In an alternate world, she will peer into the porcelain bowl of the toilet and see it smeared with muck.

Eddie floats her eyeballs in an elongated metal tray of Japanese ink. They stay there like clouds waiting for a storm to disperse them into thin pluvial nightmares. The tray has dimensions of 22×8×10 inches. She is soaking her eyeballs overnight, like mung beans, like Chinese mushrooms, like kidney beans. This is her way of softening her gaze on her incestuous impulse.

Shen’s language is poetically introspective, movement-driven, where Nao’s abstract in a static, object-oriented way. The middle where they meet is their subject, a tender and humorous ero guro nansensu. Besides ocular perversities, Eddie engages in 69ing with trees, face-swapping, and romantic diarrhea. For the inspired and lucid dream logic this novel occupies, these symbols collapse into some sort of verisimilitude: it’s all too strange not to make sense. You will see your own love life in this obscured mirror, and the realms of the living and the dead will become impossible to parse. It induces a derangement of the senses most appropriate for a season in Hell.

Although Funeral defies comparison, I’m reminded of the Sōseki’s Ten Nights of Dreams, with its Orphic quality, of Acker’s parodic cut-ups, and of such avant-garde culture grinders as Donald Duk by Frank Chin and Dictee by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. But that’s all to say that, if Vi Khi Nao and Daisuke Shen were boxers, they’d be heavyweights. Using a cult classic film as their template, the authors have dug so deep into the bones of Sophoclean tragedy that they’ve propelled themselves into a symbolic language of the distant future. Hell is eternal, but it seems to be forever changing. Acquire this map or be lost forever.

Conor Hultman lives in Oxford, Mississippi.

More Reviews