Sit with Me on the Edges | Talking Present Tense and Prodigal with Andrew Bryant

The first time I remember meeting Andrew Bryant was at a Magnolia Electric Co. show at the Hi-Tone in Memphis in 2009. I’d seen Jason Molina and his band about nine or ten times before that back in New York (I’d also traveled to Philadelphia to see them), and now I was living in Oxford, Mississippi, and venturing to see Molina and Co. tour in support of their latest album, Josephine. Andrew also lived near Oxford, and we hit it off as Molina fans. I also remember talking to him about the poet Frank Stanford, whom we’d both just read for the first time. My memory is blurry beyond that. I hadn’t heard Andrew’s music yet, but I would soon. We couldn’t know at the time that it would be the last time we’d see Molina play—he’d been so prolific both in terms of putting out music and touring, and I’d seen him at least once a year since discovering him in 2001. We couldn’t know that he’d fall off the map after that Josephine tour and that he’d be gone within four short years.

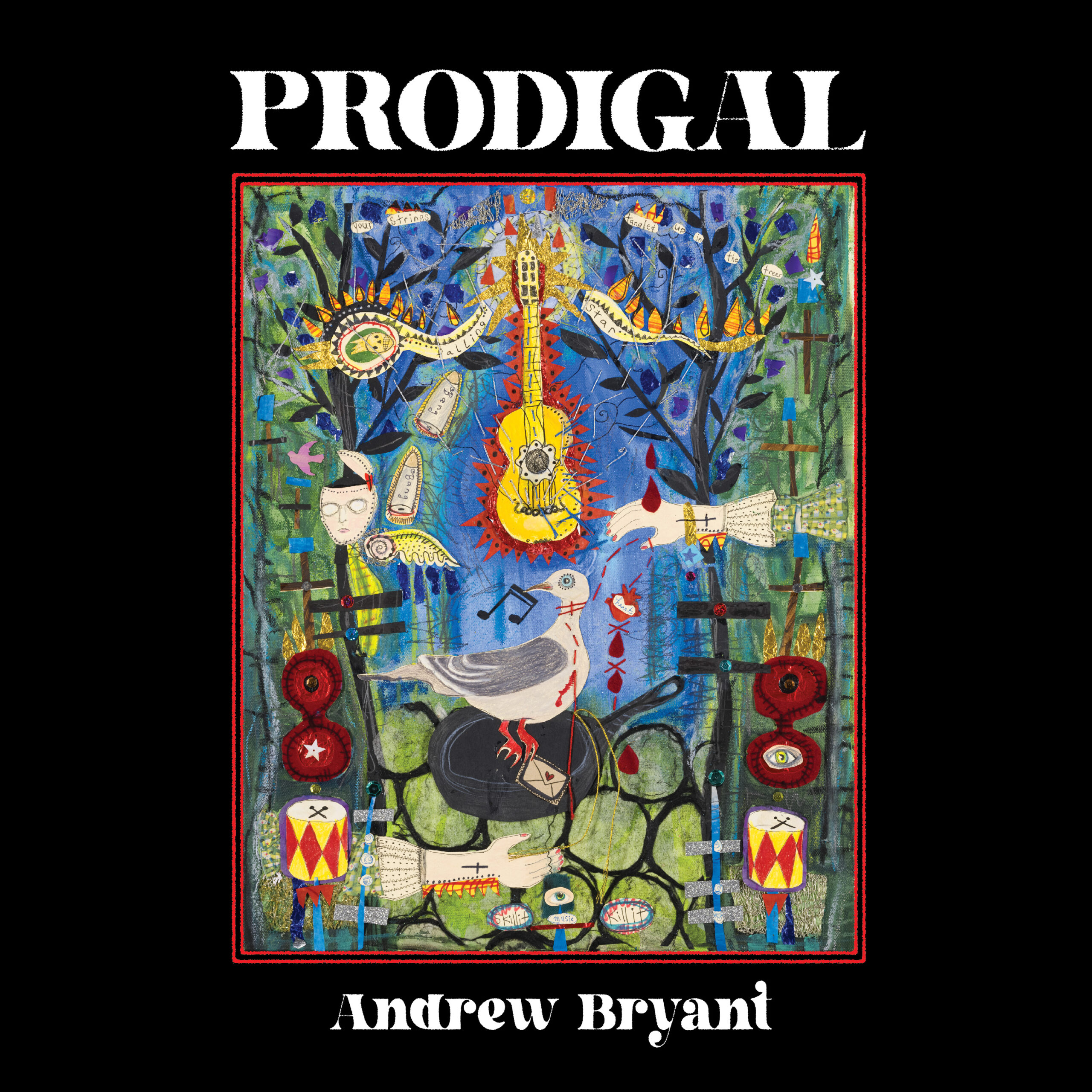

Sometime after that Memphis show, I saw Andrew open a show for David Bazan. I think it was the first time I heard him play. Then he and Justin Peter Kinkel-Schuster started the band Water Liars, and I was on board right out of the gate. My pal Jimmy Cajoleas and I saw them play their first show, and I never missed them after that. (I’ve written more about that here.) Water Liars had an incredible three-album run before splitting up (they’ve since released their “lost” fourth album and gotten back together for a reunion tour), and both Andrew and Pete have been prolific in terms of releasing knockout solo material. Bryant had released solo material before his time in Water Liars, but I really started paying attention in 2015 with This Is the Life, one of my favorite records that year. He followed with Ain’t It Like the Cosmos (2017), Sentimental Noises (2020), and A Meaningful Connection (2021), all stunners. Now he’s released Prodigal, an album that finds him digging back into his childhood in Mississippi. And then there’s Present Tense, a deeply personal documentary about Bryant and the making of Prodigal by filmmaker Gerard Matthews. Andrew and I discussed both the album and the film.

William Boyle: Given our mutual love of Jason Molina, it feels only right to start with him. In the press release for Prodigal, you talk about Shiloh being the informal name of the first place you remember living and about connecting deeply with Molina’s song “Shiloh Temple Bell,” aka “Shiloh,” from Sojourner and Josephine for that reason. Your song “Shiloh” here directly echoes Molina’s, and Present Tense, the accompanying documentary about the making of Prodigal, opens with a bit of your cover of Molina’s “Shiloh” (a picture of Molina can also be seen on the wall behind you in one of the early interview sequences). Prodigal feels like it’s cut from the same cloth as Josephine; coincidentally, there was also a documentary made about the creation of that album, Recording Josephine: Magnolia Electric Company at Electrical Audio. Can you talk a little about Molina’s continuing influence on you and on Prodigal and Present Tense in particular?

Andrew Bryant: I know we’ve talked a lot about Jason Molina over the years when it pertains to my work, so I hope it’s okay we are starting here again. I’m always fine with it. The influence he’s had on my songwriting, the way I approach my work, my stories, and my recording process is vast to say the least. I’m not sure if you’re following the Static & Distance Substack started and run by Molina’s label, but they do a really good job of unearthing tapes and drawings and things like that, which as a fan you love to see. But what I’ve discovered is that I’m finding out some of my natural tendencies seem to line up with his as well. Like collecting random things and having random ideas of songs floating around on tapes and other things that are just scattered everywhere. I’m like that too. My studio is full of those things. And I think for this record, I started rummaging through a lot of that stuff and it helped. I really don’t listen to Molina’s music as much as I used to. It can be so dark at times, and at this point in my life, I honestly just find that I don’t relate to it on most days. But I do find times to sit with his songs, when the time is right, and every time I am floored by the mythic-like world he created that spans albums, and that’s something I’m trying to tap into as well—that deep oral tradition of telling tales through song. “Shiloh” was perfect for that because, like I’ve said, I grew up for many years in a ghost town called Shiloh here in Mississippi. My mother has recently moved back there, and I still visit there, so I needed to write my own version.

WB: Prodigal finds you looking back at the past, at where you were raised and the people who surrounded you. It’s an album very much rooted in place (though there aren’t a ton of specific place names mentioned), and there’s a cast of characters and varying points of view in these songs. In Present Tense, you say that Prodigal “feels more mythical but it’s not.” I’m very interested in that line between the personal and the mythical. You also say that the album was an act of healing and of reappraisal, that it ultimately became about showing grace toward people you’d maybe previously rejected or resented in some way. Where did these songs come from? How did the album take shape?

AB: I think leaving the place names (other than Shiloh) out was an intentional decision on my part because I wanted to be more specific, more concrete, when making this album. The places that are mentioned are “creeks,” “gardens,” “backyards,” “trampolines,” “fields,” “tree lines.” I kept it vague because I wanted the listener to sit with me on the edges, in the corner, as an observer. When we look at things from one perspective, and when we tell things in our own way, the line between myth and reality gets blurred, so I wanted to hold space for that. But it is wild for me to be able to visualize every blade of grass, every creek bank, every field and road on the album, specifically, knowing that the listener can’t. So, I had to find a way to get them there. Therein lies the myth for me. I wanted the album to have that essence in order to bring them into the space without judgment by making them curious about the place. The album started as a memoir actually. My childhood best friend died (in 2020) in the middle of me trying to write, for the first time in longhand, about my childhood and all that had happened in it. But I grew weary of that medium quickly and thus switched the project to song, which I’m just much more familiar with and now know suits the tale much better.

WB: Present Tense is a film about the making of Prodigal, recorded at Bruce Watson’s Delta-Sonic Sound Studio in Memphis, but it also feels much bigger than your standard making-of documentary. You’re tangling with the past, exploring the place that you’re from, digging into relationships and memories, discussing anxieties about performing, and really opening the door on the act of creating art. It’s one of the more remarkable and honest works I’ve seen on the creative process. You often record your albums at home—what did it feel like to be in the studio and to have someone documenting your process? Your partner, Sarah, and the band play key roles—it’s about the art of collaboration, as well. How did the documentary come to be? Given the fact that the songs on this album are largely about looking back, what does the title Present Tense mean to you?

AB: Originally, the filmmaker, Gerard Matthews, had approached me about making something much shorter, focusing more on my sobriety as a musician (I’m three years sober from alcohol), but after his first visit to my studio, in which we shot the interviews and some performances, he seemed to think there was more to tell, so I invited him to the studio a few weeks after that and he just kept coming around for a while until it was done. Normally, recording with a film crew around is not ideal, but he was just one person, so having him there was like having just another studio hand around, and mostly even less than that. He’s a real pro and made himself a fly on the wall for ninety percent of the time.

As far as the film title goes, Present Tense was all his idea, and it seems to come from the narrative that he saw unfolding as I worked on the project—which is that I was a little tense in my present self while being so vulnerable about my past. The old Faulkner trope really came to life for us and hit hard as we were making it. There really is something to the past never being dead.

WB: I love the moment in the film where Rick Steff says he “could see the rooms you were walking in.” How do you see those rooms when you’re writing and performing? What is the act and art of interrogating memories like for you? Is it rooted in sensory details?

AB: When I was writing the album, I was entering a lot of spaces in my youth that gave me joy or peace, but I was surprised every time by the fear and anxiety that also crept in. There were memories that I’d buried in my soul or mind or wherever that came up out of nowhere, and then I had to confront them. I think that comes through a lot on the record. The sensory details bring up so much emotion—pain, sadness, joy, peace, love, hate—because they are from a place and time where all of that was present. I suppose I could have ignored the bad and only focused on the good, but that feels dishonest, and so I didn’t do that. And as far as performing through it all, that’s a whole other thing. I did a lot of things to keep my anxiety under control during the making of this album. And for the most part, it worked, because the end result is exactly what I wanted to make.

WB: In Present Tense, you stumble into an abandoned church (somewhere near Bruce, Mississippi, I take it) that’s “falling in on itself.” This space becomes very symbolic and seems to represent something about the themes of the album. What did you feel in that place? Why and how did it become so significant?

AB: I’d been thinking a lot about a version of “the place” that the album is about that was strictly from the past, or memory. And in the past, that church was a functioning church. But in the present, it’s literally falling in on itself. I wouldn’t say I liked that metaphor, but I took it as one. The place where I was raised still exists, and the ideas I was raised on are still there too, but it’s slowly crumbling—the town buildings, the churches, and the people. So, I explored the space as an archaeologist might, to see what was left behind, what was still there, in a place once considered holy and sacred. I sat in that space in reverence and listened for what the ghosts could tell me.

WB: In your songs, your religious upbringing—the certainty you were surrounded by—clashes with your doubt (“I don’t know shit,” you sing on “Certainty”). You’re often tangling with feelings of estrangement and identity in ways that feel honest and raw. Is there a yearning for the sense of certainty about the world you must’ve felt as a kid? Is that part of what you’re confronting here?

AB: I think I am still looking for that certainty. That childlike trust that what is told is the truth. But I don’t feel that in my older self. I feel more doubt than ever in some ways. Although, I would say making this album has brought me closer to my spiritual self. I’m not practicing anything at the moment, but I find myself comforted by the idea that this life is not all there is, even with all my doubts of who or what exists outside our minds.

WB: The cover art for Prodigal is by one of my favorite artists, Blair Hobbs. How did that come to be? Why did you think Blair’s work would be a good match for this album?

AB: I’d been following Blair’s work for over a year when I was making the album. And when I am making demos for my albums at my home, I often make a listening playlist on my phone to work on ideas, and I always give the playlist an art cover—whether it’s a pic from my phone or just some image I see somewhere. For whatever reason, she had posted a brightly colored collage the day I finished demoing, and it was a beautiful piece of a butterfly. I used that image for my own personal use for the Prodigal demos, and I liked it so much that I reached out to her to see if she could create a piece based on the lyrics and music from the album, and she did. She actually made two and this is the one I chose. I wouldn’t say she was reluctant at first, but she’d definitely expressed that she’d never done anything like this. But what she made, I think it’s wonderful. It represents the collage of memories that lie both in my head and on the record. And now it hangs on my dining room wall as a reminder as well.

William Boyle is the author of the novels Gravesend, The Lonely Witness, A Friend Is a Gift You Give Yourself, City of Margins, and Shoot the Moonlight Out. His novella Everything Is Broken was published in Southwest Review Volume 104, numbers 1–4. His website is williammichaelboyle.com.

More Interviews | Music