Talking Rumble through the Dark and Desperation Road with Michael Farris Smith

Interviews

By William Boyle

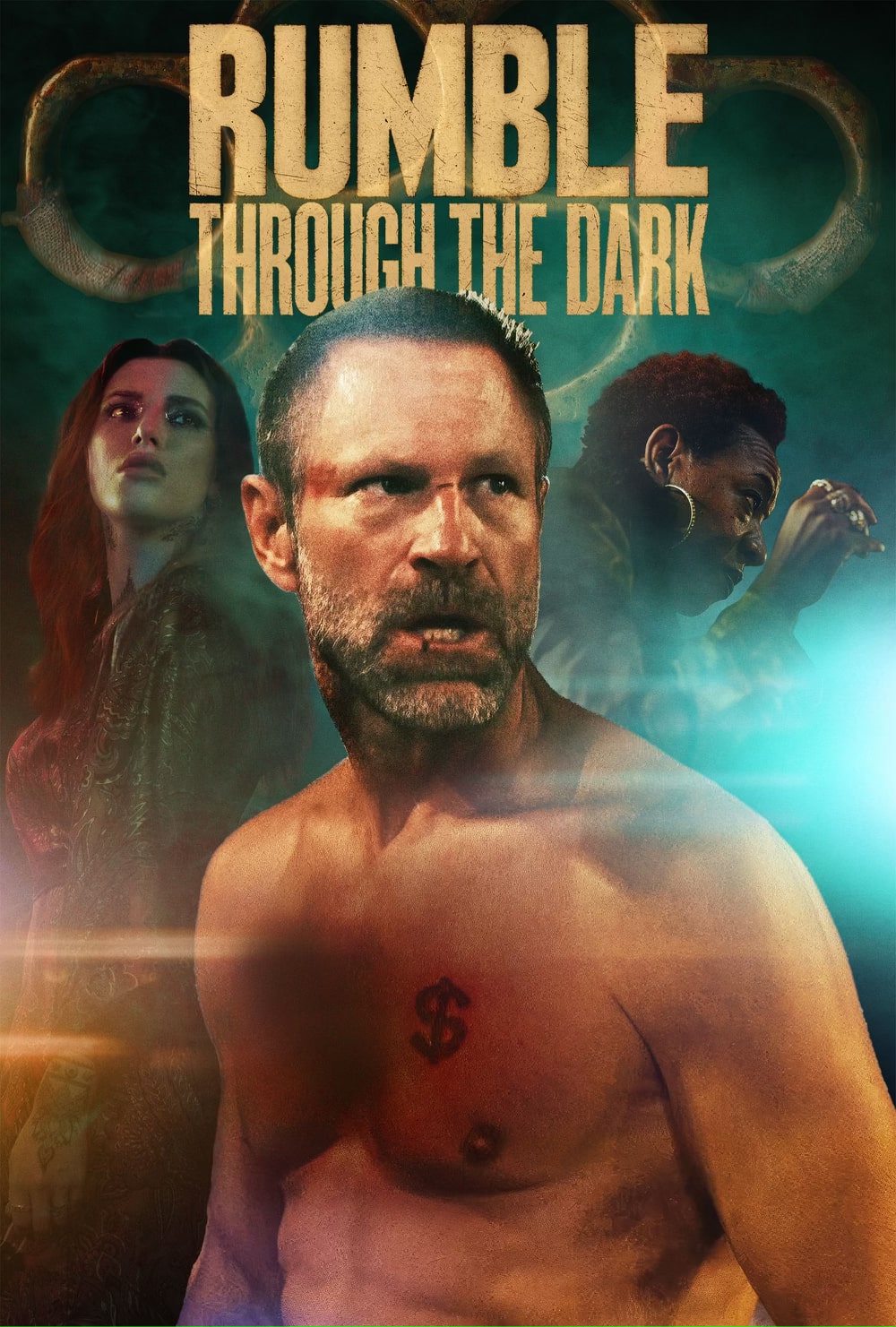

It’s a risky thing when a novel you love is adapted into a film. There are just so damn many unknowns. Who are the people making it? What are their motivations? Can the actors inhabit the world of the story—cut to the heart of it—without losing what made it work on the page? Even if things go wrong, which they invariably do on movie sets at some point because of all those moving parts, they must cohere into something that captures the spirit of the prose to be ultimately satisfying. Author Michael Farris Smith has had two of his knockout novels, The Fighter and Desperation Road, recently made into films and released out into the world almost simultaneously. The Fighter has become Rumble through the Dark, directed by Parker and Graham Phillips, and Desperation Road is directed by Nadine Crocker. Smith wrote the screenplays for both films, and both are terrific character-driven studies of place and memory and trauma, anchored by strong performances from surprising casts. I talked to Smith about the two films and the art of adaptation.

William Boyle: How did Rumble through the Dark come about? Did Parker and Graham Phillips read the book and get in touch with you? Had you seen The Bygone? Did you have a good sense right away that they’d be the right people to direct it?

Michael Farris Smith: The Fighter was originally optioned by producer Cassian Elwes, who has done films like Dallas Buyers Club and Monster’s Ball. We were some months into that when, out of the blue, I get an email from Parker Phillips, introducing himself and Graham, telling me they had read and loved The Fighter and wanting to know if it was available. I put them in touch with Cassian and they started talking. Then they sent me The Bygone to watch to show me their work. I was about five minutes into The Bygone, saw the use of landscape and how beautifully it was shot, and I thought, These are the guys.

WB: What was the process of adapting The Fighter into a screenplay like? You can obviously do things with language, interiority, and memory in fiction that are much harder to pull off in a film—how did you try to get to the heart of the book without sacrificing anything? Is the art of adaptation to you about stripping things to the bone and getting to the most essential beats of the story? Had you worked on scripts before? Did you study any screenplays for inspiration?

MFS: It was damn sure a lesson in economy. How do you take a 300-page novel and put it into 100 pages and still get the emotions, the nonverbal elements, the backstory, all the stuff you need to make it feel like the novel?

I tried to think about it like this: Get the bones of the story first, the foundation that’s going to make it stand up. And then bring as much of the color along as you possibly can. I feel like I’m fortunate that I’ve always thought about writing prose in a cinematic way, trying to help the reader see more than anything else. I think that mindset really helped me when I began trying to adapt. I had a feel for hitting the image, then moving on. Giving the dialogue that matters, then moving on. I had never done a script before, but not far into it, I began to get the feeling that I could do it and maybe do it well. And I wanted to. We’ve all heard the horror stories of novels being adapted and you can’t recognize them on the screen. I wanted to do the best job I could with the script so that I could stay involved.

Like with most things, I turned to my favorites. I looked at a couple of the Coen brothers’ scripts. I looked at the script for The Assassination of Jesse James. But not too much study. I tried to get a feel for how it looks and how it moves and then go and figure it out myself. I was hoping my style, whatever that is, had a better chance of showing up that way.

WB: Rumble through the Dark was shot on location in Mississippi. The landscape really plays a major role. Did you talk to the Phillips brothers and cinematographer David J. Myrick about how to best capture what makes the Mississippi landscape unique? Did you have visual inspirations—photographers, other films—that you pointed them to?

MFS: To their credit, they took the responsibility of capturing the Mississippi landscape upon themselves. And believe it or not, they had never been here, but they really felt the sense of place in reading The Fighter. The first thing they did when we all agreed to work together was get on a plane and fly out. I met them at the bar at City Grocery. We talked about Mississippi, the Delta. Myrick brought his camera and we got in my Jeep and went riding, looking, discovering. They didn’t want to do anything that wasn’t real. All I had to do was drive them to the right places. I feel like the Mississippi landscape is a wonderful playground for filmmakers that speaks largely for itself.

WB: How does what’s on the screen compare with what you saw in your mind? Did anything about the performances, particularly by the four leads—Aaron Eckhart, Bella Thorne, Marianne Jean-Baptiste, and Richie Coster—surprise you? They all do strong work and feel well suited to the world of your story.

MFS: What has been really interesting to me is this: I had only heard those characters speak in my head. In the novel, even in the script. Then the actors show up, and they deliver a line differently than you hear it, with different inflections, different tones, different emotions, and it becomes something unique again.

Aaron Eckhart, when his name came up, made us all sit up. It seemed like such an interesting choice, and then when he read it, and gave us all the reasons why he was drawn to it, it was a little bit astounding because we knew we had found the right Jack Boucher. Same with Bella. I remember she posted a photo on Instagram of her reading The Fighter and I thought, This is going to be a home run. Marianne is such a powerhouse. Richie Coster is such a well-respected actor and craftsman. They all got it and they all delivered moving adaptations of the characters in their own unique ways.

WB: You were on set for the shoot. What was that like? How much input did you have?

MFS: I give credit to Parker and Graham for wanting me to be there, to spend time with the actors, to answer their questions, to do any on-the-spot rewriting, to help keep an eye on what was happening in each scene. I let everyone know I was there if they needed me, so it made it very natural for us all to collaborate and help one another.

It’s so eye-opening to watch this happen. What looks like chaos is a film crew composed of artists, technicians, electricians, costumers, and so on, a gathering of people right on point with their craft and working together to help one another and to help the project be its best. It’s really inspiring. And it’s particularly validating to be involved on set in making it all look and feel as true as possible.

WB: I’ve loved movies my whole life, but it’s only in the last decade or so—since I’ve been publishing novels—that I’ve come to understand how rare it is for something that’s optioned to actually get made. Things fall apart constantly. Not only have you had two works successfully adapted that are arriving at the same time, but they’re both damn good and true to the spirit of your books. If I’m not mistaken, you adapted Desperation Road after Rumble through the Dark, so you’d already been through the process once. How was this different? What lessons had you learned that carried over?

MFS: Yes, in the weird world of indie filmmaking, we shot Desperation Road after Rumble but Desperation Road came out first. I did learn quite a bit from one script to the next, and from the experience of being on set. I thought more about transitions from one place to the next, the timeliness of moving a crew, the efficiency of locations, the set pieces that may be too big or too expensive. It’s a weird way to have to think but I’m finding out that is a big part of doing this. Every day is money. Every hour is money. And there is only so much of it. You’re given a certain number of days to do this and it all has to fit, and it all needs to be great. You have to keep the economy in mind without sacrificing the vision of the project.

MFS: Yes, in the weird world of indie filmmaking, we shot Desperation Road after Rumble but Desperation Road came out first. I did learn quite a bit from one script to the next, and from the experience of being on set. I thought more about transitions from one place to the next, the timeliness of moving a crew, the efficiency of locations, the set pieces that may be too big or too expensive. It’s a weird way to have to think but I’m finding out that is a big part of doing this. Every day is money. Every hour is money. And there is only so much of it. You’re given a certain number of days to do this and it all has to fit, and it all needs to be great. You have to keep the economy in mind without sacrificing the vision of the project.

WB: This is a film with a handful of great performances—Garrett Hedlund, Willa Fitzgerald, Mel Gibson, Ryan Hurst, and Woody McClain are all terrific. Director Nadine Crocker is also an actor, and she seems to give the performers plenty of room. This really feels like an actor’s movie, and it’s perfectly cast. I’ve admired Garrett Hedlund since I saw him in Friday Night Lights, and he particularly stood out in Country Strong, Inside Llewyn Davis, and On the Road—he’s a perfect fit for Russell Gaines. And Willa Fitzgerald has blown me away in several things recently—she gives a stunning performance as Maben. What was the casting process like? How much input did you have? And Crocker is a great match for the material—how did she get involved as director?

MFS: Cassian Elwes produced this film as well, and when we were together on set in Natchez, he mentioned he had a director in mind if Desperation Road was available. Strangely, I had just pulled the rights back, so I passed it to him and Nadine loved it. We pretty much kept going from that moment until the end.

I agree completely about this cast. I was a little stunned by how wonderfully it came together—when the names kept popping up, I knew the cast was going to be a strength of this film. Garrett Hedlund really gets a lot of credit for this. He was the first to read the script and it took him about two days to call us and say he not only wanted to play Russell, but he loved the story and wanted to do what he could to help recruit a great cast. Ryan Hurst blew me away. Woody McClain was such a great find. And Willa. Willa is getting a lot of attention for her performance as Maben and rightfully so. The entire cast showed up ready to do this right. There was also some guy named Mel Gibson, who did okay.

WB: The film takes place in Mississippi but was shot in Kentucky. Still, it feels right. Did shooting out of state cause any issues in attempting to capture the spirit of the place, which is so central to both the book and film?

MFS: That’s where the real work came in, finding the town and the places to make it look like Mississippi. We had already scouted McComb in South Mississippi, where the story is set, and thought it would be shot in Mississippi. It didn’t work out, but we had the advantage of having already seen the places that exist in the story, so we had a great visual game plan. I also think we got lucky shooting in the fall because the colors of the hills and trees of the Kentucky landscape added some lovely dimension and texture to the film. I think it’s just gorgeous in the way that all of the South can be.

WB: I feel like the spirit of Larry Brown really hangs over this one. I know how much you admire his work—were you thinking about books like Joe and Father and Son when you wrote the novel? Were you thinking about David Gordon Green’s film adaptation of Joe while adapting the book?

MFS: You’re right. Out of all of my work, those two novels of Larry’s probably have the most influence on Desperation Road. Just something about the aesthetics and mood of those novels really bled into Desperation Road. And yes, I did think about the film adaptation of Joe. I thought it was a faithful, strong adaptation that really stuck to the guts of the novel. I watched it several times, thought about it, hoped that what we could make with Desperation Road could have that same sense of place, dread, tension, and salvation.

WB: In the great tradition of authors having cameos in film adaptations of their works (my favorites include Charles Bukowski in Barfly, Charles Willeford in Cockfighter, Denis Johnson in Jesus’ Son, James Dickey in Deliverance, and S. E. Hinton in both The Outsiders and Rumble Fish), you have a cameo in Desperation Road. What was shooting that scene like?

MFS: Nerve-racking. It sounds like a lot of fun to make a cameo until you’re standing in a scene with Garrett Hedlund and Ryan Hurst and the director is getting ready to yell “Action.” And then all you can think is, Don’t screw this up. Then when it’s over and you’ve done it and survived, you think, I’m ready to do that again. A vicious cycle.

William Boyle is the author of the novels Gravesend, The Lonely Witness, A Friend Is a Gift You Give Yourself, City of Margins, and Shoot the Moonlight Out. His novella Everything Is Broken was published in Southwest Review Volume 104, numbers 1–4. His website is williammichaelboyle.com.

More Interviews