The Devil’s Most Valuable Work | An Interview with Daniel Guebel

Interviews

By Jessica Sequeira

It was years ago that I first read Daniel Guebel, and I have a vague memory of a banquet. Or rather: an Argentine asado, one that describes the foods of a barbecue in rich, nauseating detail, leading me to think of descriptions of banquets in philosophy and literature from Maimonides’s ruminations on the Purim feast to Rabelais’s delectations in Gargantua and Pantagruel. Is Guebel a Maimonides or a Rabelais? He is somewhere between, perhaps, poised delicately atop or crudely straddling the line between (on the one hand) the rows of glasses, fancy napkins, cut fruits on trays, and polished silverware, and (on the other) the heaps of raw meat that sizzle and brown on a rack prior to their being heaped upon a dish, awaiting the plunge of a big knife before everyone tucks in, without fanfare and with a delight even those who do not eat meat can partake in. A precise metaphysics, born of sorrow, cohabits with a robust joy.

Yes, it was 2014 that I first read Guebel in Buenos Aires, in a book about a tremendous banquet whose details I can’t remember and won’t look up now. Biographical information would only be distracting, since we’re in the realm of not po-faced memoir but poet-faced fiction, with its wild invention and glorious freedom. What do I love about Guebel’s writing? He’s obviously clever. But more importantly, he’s not just clever. He invents many symbols, but never lets them overtake his characters, who remain flesh and blood. Last time I chatted with him, my random playlist struck up “Noche de rosas,” a popular tune by Quilapayún with Victor Jara, with its to-me-unintelligible Hebrew syllables that speak of “a threshold at your feet.” What is a threshold? Where can it be? For Guebel, it might possibly be at one’s feet, but it could also be in the mouth, and most certainly it could be in time, which is not linear but fizzes like the soda you just spritzed into your red wine this hot day.

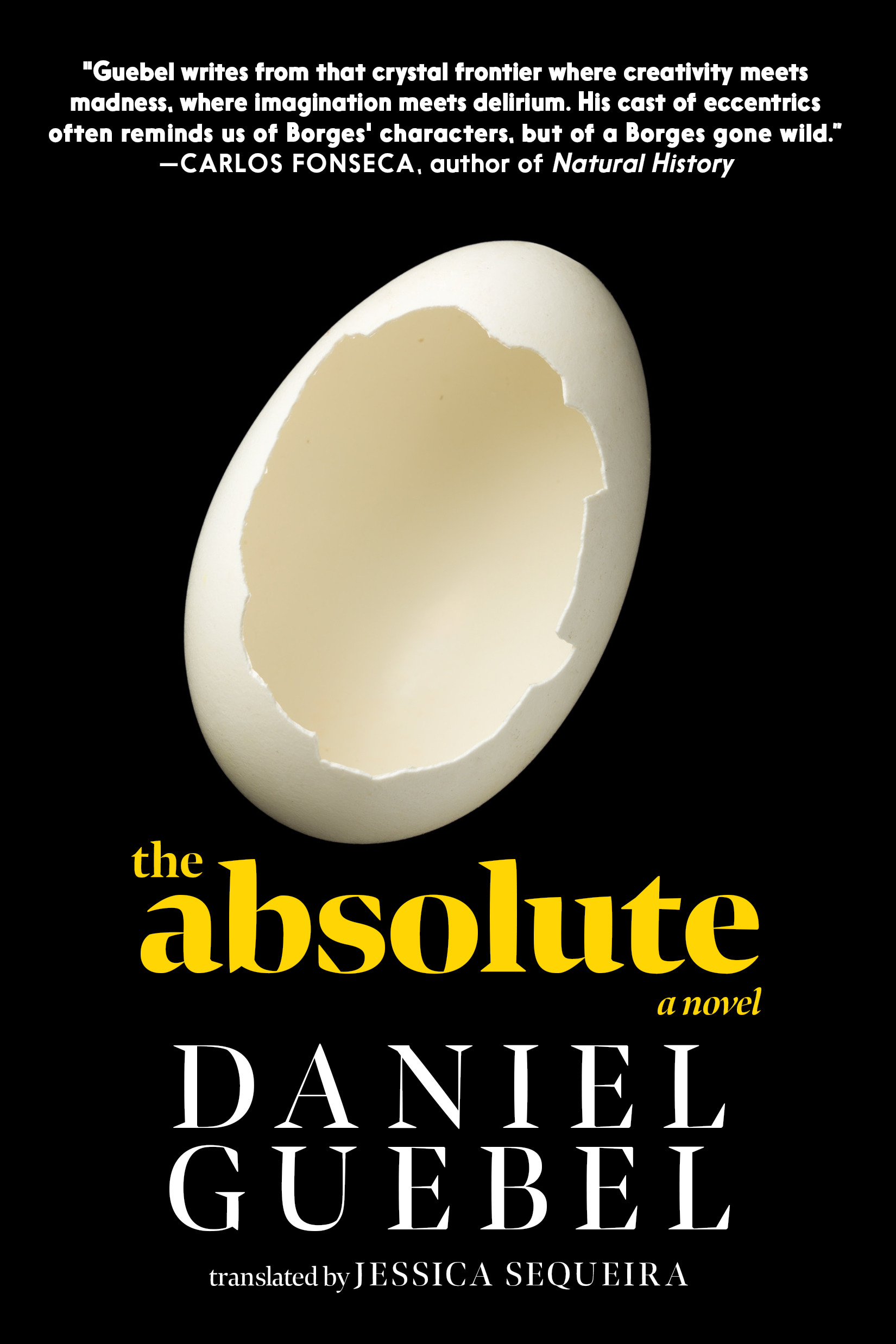

Somewhere in the old Jewish tales that it’s evident Guebel has read closely, a claim is made that ancestors can enter the soul of a bedeviled man to comfort or instruct him. Somewhere else, it’s said that if you meet an extremely vile individual, you can at least hope he has an equally luminous counterpart. I say: Think of all the books that have not impressed you. Now think of a book that is their reverse. An English barrister once made a snide allusion to those obscure books that “seldom fail to interest their translator,” but The Absolute (Seven Stories Press) wouldn’t be included in such ranks, I am pleased to say. The novel is remarkable, and I am very happy to have worked on it.

Jessica Sequeira: It’s possible to read The Absolute as a version of the Faust story, in the sense that people make sacrifices and agree to pacts in the name of artistic creation and its splendors. The devil never explicitly appears, but perhaps is incarnated as concrete characters within history. At the moment, I’m reading The Devil by Giovanni Papini (in the translation by Vicente Fatone), which presents the devil as a figure of paradox. The book ultimately argues that evil is necessary for good. It says that the artist needs confidence in him or herself to create, although hubris can also be a sin, and both confidence and hubris are linked to the devil: “An artist who does not have some familiarity with the Devil, even if only to avoid or dominate it, cannot be a true artist.” To what extent did you deliberately take up ideas of the devil, and specifically the Faust story, in your novel?

Daniel Guebel: The devil is one of the most constant presences in the unreality of my life. When I was a boy, just yesterday it seems, my parents went out to dinner with another couple, hiring an evangelist as my babysitter. In the attempt to make me sleep, he told stories of salvation and damnation: vivid images of heavenly bliss and even more intense descriptions of hell’s torments. High flames, crackling flesh being consumed, curling skin, squealing human grease, screams of the burning. He took special pleasure in emphasizing that these punishments had no alleviation—that they were eternal suffering. Occasionally, while talking about all this, sitting on his chair, he’d throw back his head, stop for a few moments to contemplate the scenes he was narrating, and surrender to the ecstasy of someone mystical or depraved. The last time, coming back from this moment of orgasmic self-gratification, he delivered his verdict: “Of course, since you’re Jewish and don’t believe in Jesus, the Son of God, you’ll go to hell.”

The sinister moral struck fear into my heart, and I began to grow afraid that sleep would bring death. I tried to stay awake at night, imagining the devil would come looking for me and if he found me sleeping, would assassinate me with a stab of his trident. The supposed lucidity of the insomniac is really the consciousness of horror. Years later, I wrote a free theatrical adaptation of Goethe’s Faust, even though I much prefer the versions by Marlowe and Estanislao del Campo. Goethe’s ending, which rescues Faust at the last minute, demonstrates a sickly-sweet piety, the worst of Catholic hypocrisy. Seeing how the devil is the most artful deceiver of the universe, victory should fall to him. Over the course of that work of adaptation, I learned the difference between tragedy and farce. In tragedy, antagonists cling to their word until the end, no one gives way, and everyone is possessed by the truth of the discourse they inhabit, unleashing the blood-soaked event. In farce, what’s in play is not truth but falsehood, a lie that passes itself off as its opposite, so that the one who tricks his opponent comes out on top.

It’s clear by this point that I’ve repeatedly avoided giving a direct answer to your question, and before doing so I must say that the devil is a reordering or compound of the old gods nascent Christianity folded into its cult; it borrowed from them, and made them more terrible, and in the end, it destroyed them. As a part of that reformulation, Christianity took up and rewrote the myth of Prometheus, calling it Lucifer, that is, “maker of light.” Hell, at bottom, is the light of reason, which should never have been transmitted to the human species by Prometheus or the serpent-demon that tempted Adam and Eve, assuming God wanted us slobbering away like happy idiots in Paradise.

Somehow, with the passage of the years or the confusion of my thinking, the agony of Christ on the cross and his incomprehensible sacrifice have become to me an equivalent to the passion of Prometheus, whose will to save humanity was punished by the gods. As you know, he was chained to a rock situated at the height of a mountain for the remainder of his days, condemned that a vulture gnaw at his liver for eternity.

I’m going to reply to you now. Never, throughout all the time of writing The Absolute, did I give a thought to the devil, but I did contemplate the way that the light of art can save us. In the end, without realizing it, by thinking about Prometheus I’ve come to consider the devil a savior, and art the devil’s most valuable work.

JS: In your recent book Un resplandor inicial (An Initial Radiance, Ediciones Ampersand, 2022), which describes the genesis of your various books, you say that “The Absolute came to me swiftly, tumultuously.” You further describe it as “a book about the expansion and risk of the universe, about salvation by art and the apparent failure of every dream to transform reality, a book about the way that a legacy is transmitted; a book, at heart, about love and family and loss.” Can you sum up how you came to write The Absolute, in a moment that derived from chance but incorporated many thoughts already in your mind?

DG: Chance is the external motor. It is the asteroid that crashes into us and diverts us from our trajectory, which is governed by a determinism whose ultimate meaning (if it has a meaning) escapes us. The Absolute is the condensation of a number of happenstance perceptions that assembled into more complex happenstance. At twenty years old, I wrote my first readable story, “Flowers for Felisberto,” based on the biography of the great Uruguayan writer Felisberto Hernández, a pianist who played Stravinsky in the concert halls of lost towns as clucking chickens trotted by the stage (Stravinsky plus chickens = aleatoric music). Not long after that, I listened for the first time to Alexander Scriabin: a post-Chopinian musician, creator of the mystic chord, theosopher and megalomaniac. He believed himself to be a universal savior, and went mad by the grace of God (who does not exist). His combination of unbridled romanticism and atomic explosiveness disoriented me. The cover of the LP I listened to (Horowitz Plays Scriabin) complicated the matter with a provocative quote by Stravinsky: “Who is Scriabin? Who are his ancestors?” The two questions presented themselves to me as an enigma without resolution, but a couple of decades later it occurred to me to write a response, one as imaginative as it was erroneous about the intention behind the question. The glories of misunderstanding! Where I’d understood Stravinsky to be speaking of mystery, and had thought he’d been moved by the appearance of this colleague whose work changed everything, what he’d actually done is relegate Scriabin to the category of artists without precursors—as a kind of barbarian, savage, or musical illiterate. It’s as if Stravinsky had asked: “Who’s this beast sitting at the table with the wild idea of attacking his food without fork and knife, sucking on his fingers and wiping the grease over his shirtfront?”

Somehow these matters came together at the same time one beautiful afternoon, when I was on vacation with my daughter and my daughter’s mother. The night before in the hotel lounge, I’d been listening to a pianist who had suffered a stroke. It made me sad. But that afternoon in the sunshine, after days of oppressive rain, strolling through the labyrinthine, edenic garden and carrying Ana (a year old) in my arms, a bullet was fired in my mind, an explosive long-range shot. In a flash, I witnessed a scene (I don’t remember which one now) that went about unfurling at full speed before me, an iridescent fan or kaleidoscope with figures in motion, saturated with adventures and details so rich that I immediately understood it wasn’t a novel focused on a single character (because nobody could have lived so many experiences in a single life, except Methuselah) but a saga, the chronicle of a family over two centuries of history. I already mentioned the idea of Prometheus as an obsessive motor or driving force, so my impulse was to give this family the shared feature of possessing radiant genius, and the inhabitants of their world the incapacity to comprehend the reach of their work. One after another, the family members seek to transform music, philosophy and politics, and alter the order of the universe itself to save our planet from apocalypse, and travel in time toward the start of the Big Bang. (By the way, I couldn’t care less about spoilers, since writing for me is about meaning and style, not the stupid notion that a work’s value is defined by the surprise of its argument.)

A religious idea underlies all this, which inspires the artistic vocation: salvation by works. But there’s bad news. Biblically, the work alone is not enough (“For by grace you are saved, through faith—and that not of yourselves. For it is the gift of God, and does not come by works, lest any man should boast.” Ephesians 2:8-9.) Luckily for my otherworldly destiny, after finishing the novel I realized that it wasn’t just about the world and its salvation by works (even if this is essential to the universe that the characters move within), but about something more intimate and personal: the fact that I’d dreamed up my book while cradling my daughter in my arms. From the very start, writing had been about love, continuity, death, family. Because when you become a father, the importance of self gives way to the transmission of a legacy.

JS: To tell a family story might sound like something from the nineteenth century, an archaic, horse-and-buggy exercise. But The Absolute reads as very modern. How do you navigate the tension between the traditional nature of writing a genealogy, which could become antiquated or predictable, and the openness to fresh narrative explorations and surprising images?

DG: I’ve always kept a distance from the twentieth century vanguard movements. They’ve never attracted my interest. An example: modern art fell to its knees before the work of Duchamp, which can be summed up for me by the phrase about an encounter of I don’t recall what (an umbrella? a knife? a vibrator?) and a sewing machine. The intellectual click produced by labeling this heterogeneous combination as an aesthetic object endures the length of a sigh, before you keep making your way. I find greater riches in a text like Borges’s “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” which begins with a humorous quotation of the same aesthetic operation (“I owe the discovery of Uqbar to the conjunction of a mirror and an encyclopedia”), but then invents a full world that’s abundant with subtle distinctions and intelligence, with a twilight sensibility that affects the soul as long as memory lasts. To the impact of the discovery of the universe Tlön, our own gradual disintegration. In any case, if I do have any link with the vanguard or post-vanguard, it’s through my appropriation and reformulation of past artworks, starting from One Thousand and One Nights. Which doesn’t mean that I won’t suddenly do a volte-face and write something about the admirable U.S. conceptual artist Jonathon Keats. Why not embrace contradiction and the renewal of ideas?

JS: From a technical perspective, the rhythm of The Absolute interests me. It moves from conversations between individuals (or poetic descriptions of a hungry carp, Russian delicacy, bolt of silk, or stretch of river) to more general historical description, encompassing hundreds of years. It seems to me that you shift very dexterously between the personal and the sociopolitical. What was your strategy in doing so?

DG: There was no “strategy.” I’m not a professional writer, the kind who designs their book before they sit down to write it. Instead, I go about following the thread, sometimes near imperceptible, of possible continuity, pursuing its twists, diversions, arabesques. The Absolute is a river with many tributaries, and I made my way up a few of them. I didn’t explore them all. Just a few days ago, revising the novel to answer one of the questions that you asked me for your translation, I stumbled across a reference that takes up a mere three lines. It describes the arrival of Leibniz to Versailles, where he was sent as an agent of his government to present Louis XIV with a plan for the conquest of Egypt. A century later, Napoleon would attempt to carry out that plan. I’d always thought I’d learned about the visit of the German philosopher to the Sun King after writing The Absolute, and therefore had not been able to use it in the book. But actually, that wasn’t the case—there it was. Last year, I traveled back along that forgotten stream and wrote a novel, still unpublished, dedicated to that meeting in Versailles. In other words, I turned three lines into three hundred and fifty pages. In general, I’d say that I write by means of enlargement and expansion, and that more than imposing predetermined ideas, I myself am determined by prior writing.

I’ve just remembered something else. While I was playing with the stories in The Absolute, my daughter was still living with me, and we’d watch cartoons on television. Our favorite show was called Little Planets. It was a delightful program with two little plush pompoms that hopped about, traveling the galaxies and stopping to explore sweet miniature worlds: geometries made of painted cotton, each one with its own color and texture, its own adventure. I’d like to think that the novel is my version of that program, which I’m Googling now but can’t find, as if those tiny characters had been snuffed out.

As far as technique goes, I learn as I write. My approach is about perceiving the materials I’m working with and adapting to them, and coming to understand, after I crash against the same stone over and over, the crash isn’t a product of chance. You can’t break a stone with your head, however fast you come running against it. Somehow, you have to incorporate it into the body of your work, because what you can’t break in the short or long term ends up turning into the very center of your manuscript. Obviously, this is no longer just a question of technique.

Sociopolitical? Politics is a splendid game, with effects on the real, and at every moment can provide alternative models for ordering society: plots, intrigues, blood, sex, money, conspiracies. Politics is fascinating . . . as a theatrical spectacle. As far as the personal goes, it seems to me that we could mention two levels. The first is writing out of pure impulse, out of pathos (that great stone). The second, more visible, involves taking advantage of the difficult moments in your life. When you’re able to take a little distance, you discover that intense suffering has the structure of an anecdote.

JS: The Absolute could have been a very serious book, but it’s actually quite an entertaining one. What are your thoughts about comedy in literature?

DG: Whatever its proportion of sadness might be, a book always contains a few delicate drops of happiness, supplied by the act of writing. The reader is a tracker who seeks to detect those vestiges of joy accompanying the work’s creation. Given how happy I was while writing, how could I have produced a boring, solemn book? Seriousness enjoys a greater prestige, based on the false notion of profundity. But the books I love most are entertaining and happy ones (even if they have their share of torment and melancholy, their bittersweet flavor). To put it simply: Kafka and Sterne and Cervantes and Petronius and Joyce Cary and Nabokov and the duo of Borges & Bioy.

JS: Do you have any reflections on literary translation to share? Had you thought about translation before this process?

DG: I don’t really know. I’d say that I’m debuting (late) in this experience. As a good polymorph, I simultaneously wish to see my books translated all over the world, and to write books that are untranslatable, bellicose.

JS: My last question for you is about faith. Your complicated relationship with Jewishness comes through here, which is maybe a cultural or literary Jewishness above all. But there’s also a faith in human beings’ ability to keep on living and creating with humor and hope, despite a high likelihood of failure, disaster, brokenheartedness, humiliation, or disappointment. There’s a fundamental optimism and love for humanity that gives the book a warm glow in spite of the vicissitudes described, which encourages one to go on trying to dig a hole to the other side of the world, or the pub cellar next door; to go on trying to make a work of art and deep connections with other people, despite the maze of complications. Maybe here I can point toward the name of the book, The Absolute. What is your understanding of your own title, and its relation to this idea of faith that I’m indicating?

DG: I’m grateful for your synthesis. What more could I add?

Jessica Sequeira is a writer and literary translator. She is the author of the novel A Furious Oyster, the story collection Rhombus and Oval, the essay collection Other Paradises: Poetic Approaches to Thinking in a Technological Age, and the hybrid work A Luminous History of the Palm. She has translated over twenty books by Latin American authors, and in 2019 was awarded the Premio Valle-Inclán for her translation of Sara Gallardo’s Land of Smoke. She lives in Santiago, Chile and Cambridge, England.

More Interviews