The Freedom to Get Weird | An Interview with David Leo Rice

Interviews

By Jedidiah Ayres

With the June 2022 release of Crimes of the Future, David Cronenberg’s twentieth feature film (one that feels both like a thesis and yet another evolution from the auteur perhaps most immediately associated with themes of metamorphosis, mutation, progression and disintegration), time is ripe for new examination and celebration of the 79-year-old Canadian director’s singular body of work.

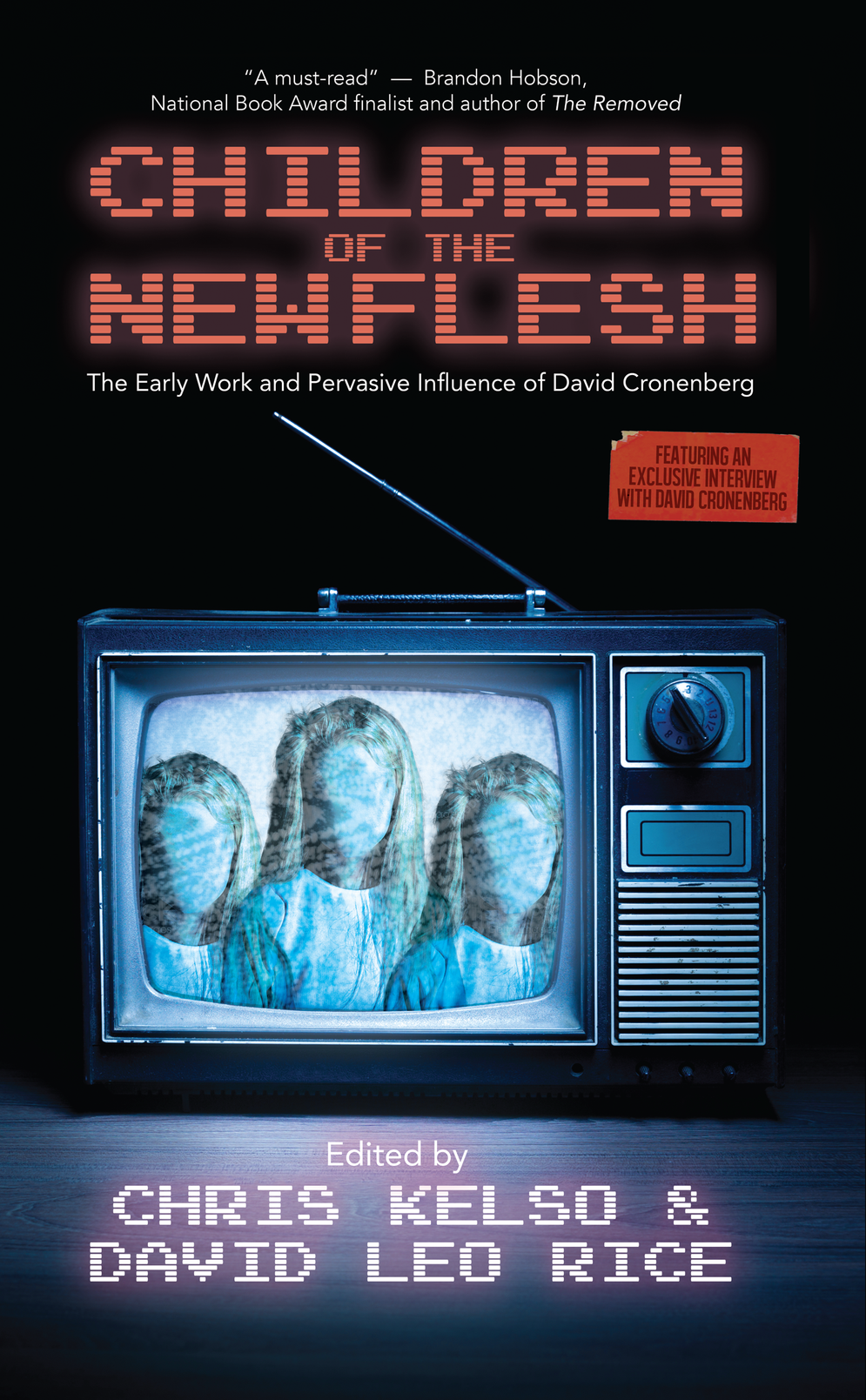

Enter Children of the New Flesh: The Early Work and Pervasive Influence of David Cronenberg (11:11 Press). Edited by Chris Kelso and David Leo Rice, this book goes back more than fifty years to examine Cronenberg’s very first films, uncovering evidence of what was to come while imagining where else the Cronenbergian aesthetic might go.

There are few artists with a strong vision and distinct enough signatures to become their own adjective. Fewer still survive without losing their way. It is extremely rare that they will continue to make quality work as true to their instincts and obsessions decades past their biggest cultural moments.

Yet Cronenberg, who has gone from upstart punk to arthouse provocateur, has kept working long enough to see his acolytes and spiritual descendants become celebrated peers and even revered elders of the form. He’s even watched his biological offspring make celebrated contributions to the subgenre that bears his name.

Children of the New Flesh features critical essays, personal reflections, interviews with artists inspired by Cronenberg, and fiction inspired by his oeuvre. I asked author and Children of the New Flesh co-editor David Leo Rice about the book and his own work under the influence of David Cronenberg.

Jedidiah Ayres: Tell me about the book’s origins. How did you decide to focus on a handful of Cronenberg’s early films?

David Leo Rice: Children of the New Flesh began with an invitation from the Scottish author and editor Chris Kelso, who’d been assembling notes on Cronenberg’s early work and was looking for a partner in crime as he set about growing them into a book. I’ve always been a committed Cronenberg fan, and have reflected often on the influence that his films have had on my writing, especially in their understanding of the corporeality of media. I even made him a character in my novel A Room in Dodge City: Vol. 2. When Chris asked if I wanted to get involved, I said yes immediately, although (or perhaps because) I hadn’t seen any of the early films yet. I was eager to learn where Cronenberg’s career began and how it developed to produce the great works we all know and love. Also, there wasn’t much writing out there focused on these very early works, so we thought the book could add something of value in that sense.

JA: Was there any concern about attracting contributors with that narrow a focus?

DLR: When we really started thinking about the shape and scope of the book, we decided that it should use the earliest films as a jumping-off point and organizing principle, but that contributors would be free to go from there in any direction they wanted: toward the later films, toward other topics in philosophy, science, politics, and culture, or into their own imaginations, as many of the pieces in here are fictions inspired by Cronenberg’s work and worldview. We did want to make sure that the book stayed grounded in the early films and gave them ample consideration in their own right, but we didn’t want to limit anyone’s contribution. In that sense, it wasn’t hard to attract contributors.

JA: It’s a unique format—mixing fiction, critical essays and interviews. Was it difficult to maintain a balance? Did anything surprise you or dramatically change the shape of the project?

DLR: We were definitely cognizant of trying to maintain balance, both in terms of writing type and also in terms of how many pieces we had for each of the seven early films. We didn’t want everything to clump up around several films and leave the others under-discussed. Our approach was to establish a basic concept from the get-go—we knew we wanted essays, fiction, and interviews in roughly equal proportion—but then to keep adjusting as the pieces came in and new authors came aboard. As in a novel, when you go from concept to reality, your concept has to be fluid enough to work with the reality that’s emerging, but also concrete enough to shape that reality in a productive direction.

This was the real joy of editing for us: to see what we had, how we could arrange it, and what else we could add from there, either by asking more authors to submit or writing more pieces ourselves. My intro, for example, was written early in the process and then revised throughout based on the evolving nature of what it was introducing. The final form depended on who was available and what they sent us, but the central organizing principle of the seven early films kept us grounded while granting us the freedom to get weird.

JA: I imagine the global pandemic lent some intensity to the contemplation of his work and themes. Did Covid shape your thoughts on what you call Cronenberg’s Heroic Pervert?

DLR: Working on this book in the “endemic pandemic” phase of Covid in 2021-22—when the initial terror and lockdowns of 2020 had subsided (in the US anyway) but it wasn’t yet clear if we’d ever be “done with” this virus or if it was something we’d be living with forever—was a crucial backdrop to how we set about considering the intersection of disease, conspiracy, and media in Cronenberg’s films. Many people have pointed out how the words “virus” and “viral” refer both to diseases in the air and to swarm or pile-on events on the Internet, but never before in my lifetime had I seen those two meanings coincide to such a degree, or understood how they travel through human systems in very similar ways, be it in the air we breathe or the stories we tell.

Here in mid-2022, as the “Covid era” seems to recede behind us, even as the virus itself lingers, I sometimes think we’ll never recover from how insane the culture became in 2020-21. At other times, I feel like we’ve already forgotten what it was like to fight over every single aspect of daily life. I’ve been shocked at how easy it is now, for example, to walk into a restaurant and eat a meal, given the rage that such an activity (as well as, of course, any impediment to that activity) caused just a few months ago. I think we may have already applied the kind of “HyperNormalisation” that Adam Curtis—a filmmaker who crops up several times in the book—discusses with regard to societies doing everything they can, often on an unconscious level, to normalize whatever new shocks they undergo, so that the full, indigestible strangeness of the situation never gets articulated.

For the purpose of thinking about Cronenberg, what I found most salient was seeing how physical and psychological disease compound each other. It seems too simplistic to say that there was the “real virus” and then the “discourse about the virus.” I understand this distinction, but the virus and its discourse felt intertwined to me, like both were effects of the same larger event that sickened many systems at once, from our respiratory systems to our financial, social, educational, and belief systems. This is where the suture between the online and offline worlds pulled even tighter, since it quickly became the case that anytime you went outside, the simple binary of “masks” or “no masks” showed what any given person believed was true about the world—a belief that, either way, almost certainly came from the Internet.

In many Cronenberg films, there’s a hazy line between science and religion, or between the atheistic and the occult. We tell ourselves that these categories are opposites: that science “saved us” from religion, or, conversely, that science is a “sin against” religion. But the reality, which I think is dawning on us more and more these days, is that the two are an unruly and ever-evolving hybrid. The most vicious culture battles in 2020-21 were framed as those who do vs. those who don’t “believe in science,” with each side, whether it be about masks or vaccines or anything else, claiming to be the true believers, fighting a holy war against dangerous apostates (the degree to which the rhetoric of each side mirrored the other was uncanny to me). This schism was fascinating to behold while working on the book, as it relates to the central tension in Cronenberg’s work, and maybe also to its central hope: that art can help us reach a plane where science and religion meld into a method that allows us to inhabit our world in an authentic, future-oriented way, beyond the reactionary enforcement or suppression of belief.

The concept of the Heroic Pervert, which is my term for the Cronenbergian hero archetype—be it Seth Brundle in The Fly or Max Renn in Videodrome or the twin gynecologists in Dead Ringers—who sacrifices his health and even his life to his own fascination with disease, mutilation, and madness, grew out of this hope. I sang the praises of this archetype out of an attempt to remain focused on my own work and metaphysical obsessions even as the world tried to pull me into one mental whirlpool or another around the manifold issues that Covid stirred up. I don’t think you can ignore these issues, but I do think that you can, as Cronenberg’s perverted heroes do, chart your own strange path through them, harnessing the sick energy of the moment for your own ends. I’m drawn to stories of people accessing an eternal realm by going through rather than renouncing the miasma of their place in history, especially since the alternative, in today’s media environment (if you don’t unplug entirely, which very few of us can), is to feed that energy back into a system that will only monetize and neuter it, turning you into a pawn of one massively well-funded “side” against another in a culture war that seems designed to grind on forever, benefiting only those who designed it that way.

JA: What, if any, effect on your own fiction do you think examining a major influence this closely will have? Has the observed thing already changed in any perceptible way?

DLR: It was definitely my goal to engage in self-reflection with this book. I love Cronenberg’s work and wanted to honor it, but I also wanted to push my own thinking forward by reconnecting with my younger self—that fifteen-year-old discovering Dead Ringers and Videodrome on VHS. I also wanted to consider those films’ influence on the community of writers that I consider my peers. I’ve written nonfiction throughout my life, but I don’t view myself as a critic or scholar. I’m more motivated by the desire to flesh out my own inner world rather than to make a point about the external one. Also, I view film as a form of meditation, inducing a trance wherein you engage in a particular type of thinking that may have as much to do with what’s in your head as it does with what’s on-screen. More so than that of most great artists, Cronenberg’s work is already heterodox and provocatively incoherent. So breaking that work down through one’s own unholy digestive process rather than scrutinizing it in a more orthodox manner seems like the best way to honor it. It wants to breed and seed new life, which we aimed to do in the book.

In terms of the nexus of Cronenberg’s influence and my fiction at this strange moment in history that feels like a cusp between eras, the biggest change I can see is a deepening engagement with the complexity of how individuals relate to systems, whether those systems are biological, technological, historical, or political. His films, including his brand new Crimes of the Future, are very astute at considering how smaller systems (digestive, respiratory, reproductive, etc.) constitute the individual, while individuals in turn constitute the larger systems that feed off of us and also force (or allow) us to feed off of them—a parasitic formulation that Cronenberg might appreciate.

The individual, be it the Heroic Pervert or any other protagonist, is the center of most stories, yet that individual also barely exists within the complex mesh of systems that make a story function and resonate within the culture. This contradiction is central to the books I’m writing at the moment, as well as to the process of writing fiction in the first place, which can’t proceed without the individualistic act of stepping away from the crowd to be alone in a room. The forces that act upon its characters form the essence of a story. Those are the same forces I want to channel and lose myself in while writing. I want my characters to dissolve over the course of the story, becoming less individualistic even as they learn more about themselves, just as I also want to go on this journey in my room, turning my aloneness into a strange, crowded world I barely recognize. This is the core of whatever religious faith I have: that truly knowing yourself and truly losing yourself are the same experience.

This also relates to another aspect of Cronenberg’s work that came to light over the course of the book, that of hybrid states as a fundamental aspect of reality. Cronenberg loves hybrids: human/insect, human/machine, real/virtual, individual/twin, signal/flesh, art/trash. At the root of this love, as I see it, is a love of the ways in which true/false and funny/sad get fused together if you think deeply enough about any topic. In this regard, I relate to Cronenberg as a Jewish artist and intellectual as well. Even if he isn’t explicitly connected to the Jewish faith (although, between Kafka and Pinter, his Jewish influence goes deep), his feeling for the type of irony that cuts through rather than deflects the heaviness of existence feels familiar to me, at least on the level of an ancestral Jewish worldview I share.

JA: Did the release of Crimes of the Future (2022) change anything for you?

DLR: The new Crimes of the Future, which I discuss here, confirmed what I’ve come to believe from watching so many of Cronenberg’s films—that there’s a genuine evolutionary process at work in his output, both on and off the screen. His films aren’t just about the strange paths that human evolution takes as our bodies and minds develop, sometimes in sync and sometimes at odds with one another. These strange paths also unfold from film to film, within a body of work that now spans more than half a century. To perceive such a body of work as an authentically living body, subject to its own growth and decay over time like Cronenberg’s own body, is extremely moving. It proves Videodrome’s thesis that signal and flesh interpenetrate on profound and mysterious levels.

Manifesting this evolution, Crimes of the Future is the first that Cronenberg both wrote and directed since 1999’s eXistenZ. It kicks off a new phase for Cronenberg, perhaps his last. I’ve taken to calling it his “monk” phase, as distinct from the punk phase of the Heroic Pervert, which centered on the idea of “wasting” good health by pursuing a grotesque biological tributary in protest against the norms of human reproduction. Viggo Mortensen’s plays an organ-removal performance artist named Saul Tenser. He’s an older man, no longer in the prime of life. Unlike the heroic perverts in Videodrome and Dead Ringers, Tenser journeys toward acceptance rather than renunciation of the new flesh. Whatever it takes, he’s determined to go on living for as long as possible, an outcome that no Cronenberg film has posited so openly before. This determination introduces a new warmth and even sentimentality into Cronenberg’s often chilly aesthetic. At last, the new flesh is allowed to thrive and augment rather than pervert our understanding of what makes us human—a welcome turn in the anti-humanistic atmosphere of 2022.

JA: What’s next for you?

As for what I’m working on now, first up is promoting my recently released novel The New House, which is about a family of Jewish outsider artists roaming the American interior in search of the New Jerusalem. I have two books slated to come out next year: the first is A Room in Dodge City: Vol. 3, the conclusion to a trilogy I’ve been working on since 2012, focused on the exploits of a nameless drifter in a fantastical, cinema-drenched version of the classic Western town. After that, there’s a new story collection entitled The Squimbop Condition. It’s about a duo known as the Brothers Squimbop who trip through time and space, manifesting in numerous guises—slapstick comedians, clowns, political charlatans, mass murderers, lonely fanatics, small-town professors—as they attempt to unravel the mystery of their origin and purpose, together or on their own. These stories have been published serially in Southwest Review and are archived here.

Jedidiah Ayres has never heard of you either.

More Interviews