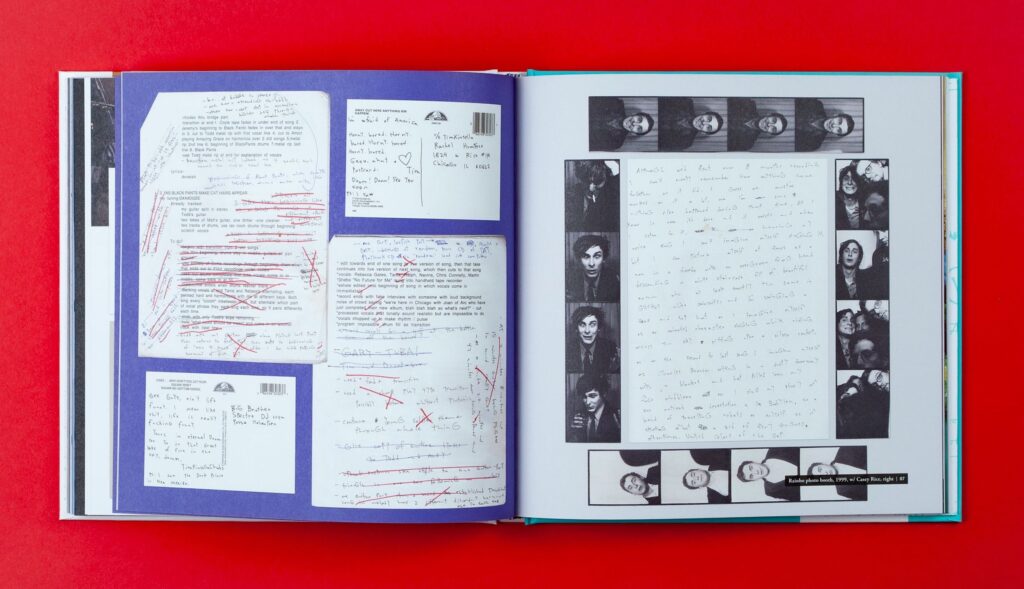

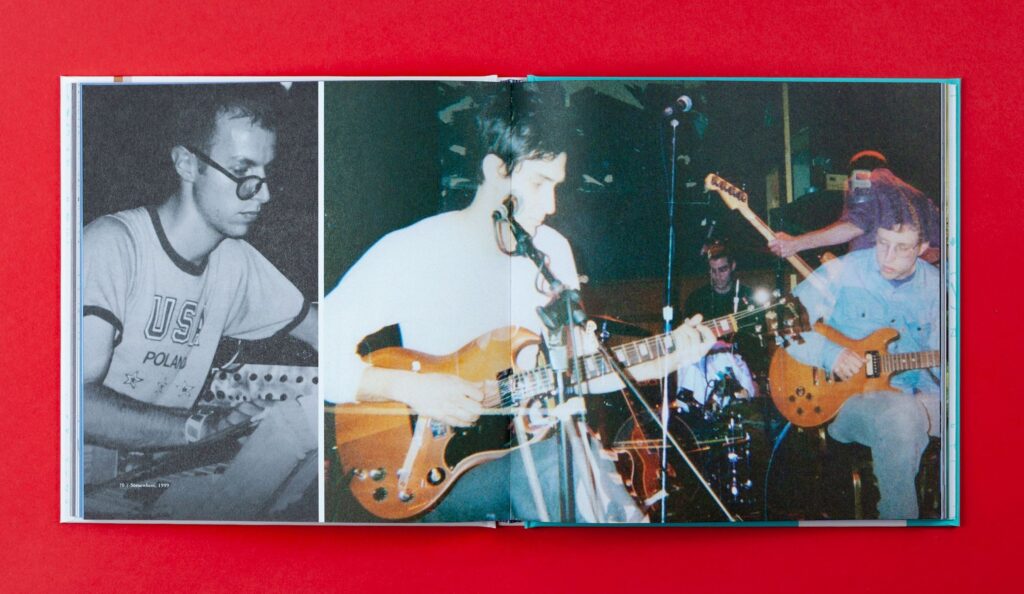

The Guest List is a regular book column that surveys the reading habits of our favorite musicians. In this edition, Jimmy Cajoleas talks with legendary Chicago musician and writer Tim Kinsella, whose resume includes Cap’n Jazz, Joan of Arc, Owls, Make Believe, and many others. He’s also the author of three novels and a collection of tour diaries. A new retrospective box set of Joan of Arc’s classic albums, A Window & a Mirror, was released in July on Joyful Noise Recordings.

Jimmy Cajoleas: What are you reading right now?

Tim Kinsella: I have pretty weird reading habits these days because I had professionalized reading for a lot of years. I taught creative writing at a few different colleges and ran a small press (Featherproof Books), so I was always editing, and reading became no fun for me. It was always my primary love after music, the one thing I always did without thinking about it. When I professionalized reading, it became a drag and I resented it. Over the last couple of years, since I quit teaching and stopped doing the press, I’ve really enjoyed reading more freely than I ever have. I have a couple of times a day blocked out for reading, so I’m always reading multiple things at once.

Tim Kinsella: I have pretty weird reading habits these days because I had professionalized reading for a lot of years. I taught creative writing at a few different colleges and ran a small press (Featherproof Books), so I was always editing, and reading became no fun for me. It was always my primary love after music, the one thing I always did without thinking about it. When I professionalized reading, it became a drag and I resented it. Over the last couple of years, since I quit teaching and stopped doing the press, I’ve really enjoyed reading more freely than I ever have. I have a couple of times a day blocked out for reading, so I’m always reading multiple things at once.

I used to really struggle with depression and anxiety at times. I don’t have that problem so much anymore, because I have a very intentional morning. I wake up an hour before I normally would, do a little yoga and meditation, and then read poems. In the mornings, I read Zen books, or the Bhagavad Gita and some poems. Late afternoon or dinner time, I usually read novels or nonfiction. I read a lot of art books, biographies of artists.

I just finished a biography of the band Crass called The Story of Crass, by George Berger, which I really enjoyed even though I’m not a huge Crass fan. I’ve been rereading these Jerome Rothenberg anthologies about different cultures’ poetries: Technicians of the Sacred is one, and Shaking the Pumpkin is another. I reread those in the morning. The other day I read Unknown Masterpiece, a Balzac novella that I really enjoyed.

JC: I’ve talked to a lot of people who have been reading Balzac lately. I read Lost Illusions last year and was completely blown away by it.

TK: I think there’s a thing in terms of novels where people are appreciating books set in a distant time more than contemporary novels. I’m thinking it has to do with the technology of reading, how it predates smartphones. Because no one wants to read about smartphones in a book. If you want to think about contemporary things, maybe you’re looking at the contemporary means of understanding them on your smartphone. People like Balzac are drawing people in more these days, and that’s what I assume is happening.

JC: I also think that nineteenth-century novels take their time, and they’ve perfected this kind of storytelling.

TK: A big shift for me these days is trying to read as slow as I can. Not that I ever intentionally read fast, but that was probably part of my professionalizing reading. But now that I just read for pleasure, I read as slow as I can, and that’s really made a difference in how I appreciate things. I read out loud to myself a lot too.

I’ve reread those Jerome Rothenberg anthologies so many times each, often aloud. A huge part of the pandemic world pre-vaccine for me was spent rereading, rewatching, relistening. I wasn’t discovering new stuff so much as going back to my favorites. I discovered that all of these things had changed so much. I think about this with the first Bad Brains album all the time, how every five years it’s like a new album to me, and I’m always discovering deeper and richer parts of it. I have lifelong relationships with certain books and records.

JC: Can you tell me a couple of them?

TK: The Savage Detectives by Roberto Bolaño is one. When I was a little boy, I used to read The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn over and over so much that I would get to the last page and just start over from the beginning. It was so much a part of me. The Savage Detectives was the same way for me when I first read it fifteen years ago. My band Joan of Arc, in our most expansive form, did a poetry zine that we sold at shows called The Visceral Realists, in tribute to Savage Detectives. It was a really exciting thing for us to do, especially considering there were twenty-five or thirty people on a project, and not all of them were necessarily writers.

JC: Any other favorites?

TK: I’ve got about 2,500 books in my apartment, and I’m trying to scan the shelves and figure out what I want to talk about. There’s just so much good stuff. John Barth. Roland Barthes. Donald Barthelme. I’m in the Bs right now, obviously. Thomas Bernhard. Borges.

JC: I remember first trying to read Correction by Thomas Bernhard and being so intimidated by this giant block of text. But once I started, it was like entering a portal. The form and style just brought you right in.

TK: It’s very trance-inducing. In terms of how reading has changed for me and how people are drawn to old-fashioned novels as we feel overwhelmed by the endless possibilities of everything available to us all the time, I think about David Markson a lot, especially Wittgenstein’s Mistress. I was a very late Twitter joiner, and I don’t know if I’ve ever actually tweeted, but I like to look at it. And every time, it feels like the David Markson books, like Vanishing Point and Reader’s Block. People are responding to these little blocks of text that become narrative threads and evolve and things fall away, and there are non sequiturs thrown in.

JC: Those novels seem to have a flow to them, even if it seems like it might be disjointed.

TK: I was thinking about that in terms of Bernhard, how Markson does a similar thing. If Bernhard is blocks of text, Markson is the complete opposite, but it still has that trance quality to me. Other big books for me in terms of this trance-inducing effect are Garielle Lutz’s short stories. There’s something about the language and the cadences working something strange in you. Peter Markus is the same way too. I guess you’d call Markus prose poetry, something I used to be very against as a concept. It’s similar to how interconnected collections of short stories don’t always work for me. There was always something missing in the narrative. I came to prose poetry with similar biases, you know. Just be prose or be poems. But as I got older, I realized that prose poetry was actually a lot of what I’m drawn to, which makes sense because those are my sensibilities in what I make. So Peter Markus uses this very limited vocabulary. There’s a lot of “Boy, mud, brother.” Not using pronouns, so you get these cadences. They’re very mythic. You can’t tell what time period they’re happening in. Are you a fan of the band Lungfish? Some people will be like, every Lungfish song sounds the same. But when you’re a Lungfish fan, someone can play you one bar and you know which song it is. Peter Markus kind of does that. His body of work is always returning to these mythic things. I haven’t thought of it in years. I’m totally shocked that’s where this conversation landed.

JC: I came late to prose poetry, but the one that got me was the Charles Simic book The World Doesn’t End.

TK: I don’t know that one, though I think I have a copy. Charles Simic coedited the prose poetry anthology Another Republic and that book was very important to me, showing me that this was a form I can appreciate.

I’m just looking at the books on my coffee table now, but do you know Julián Herbert? He’s from Mexico. He has this book Tomb Song that I really love. That’s another kind of drifty language kind of book.

JC: He’s a favorite of Southwest Review. He actually read and performed at SwR’s festival, Frontera, this year in Dallas.

TK: I interviewed him once too. He’s great. Do you know Voice of the Fish by Lars Horn? It’s on Graywolf Press. I really loved that. In terms of newer books, that’s a big one for me. It’s an amazing structure, a few themes woven together approached over and over in different structures. It’s really engaging and great.

JC: Do you feel like in your own writing and music you circle the same themes over and over again?

TK: Steve Albini died recently, maybe you heard? I’m not one to listen to my old records ever. Honestly, I’m terrified of hearing them. Occasionally there’s some motivation to relearn an old song and I’ll listen to it, but it never sounds good to me. Also, there’s a million things to do with one’s time, and I can’t imagine spending it listening to my own records. I listen to other people’s records! But I made three records with Steve in three different bands. I was talking to my wife, Jenny, about this while we were working in a studio recently. I listened to a couple of songs off each of the three records we made with him, because I had a theory that each of the three records in three different bands kind of had more in common with each other than they did with the other Joan of Arc, Owls, or Make Believe records. When listening back to them, I was stunned by the lyrics. I mean, I smoke a lot of pot, and I have a lot of tuning and grounding practices that I do each morning. And I think I’m always newly emerging into urban mystic sensibilities. But then I was listening to half a dozen songs from twenty years ago, fifteen years ago, and ten years ago, and I was like, Jesus Christ, I’m just obsessed with the same shit my whole life. But it has to feel new every time I come to it.

But in terms of books, I taught at a few different schools for a decade. But I was never going to move. I don’t want to leave Chicago. And playing music is my primary mission. So there were no opportunities for career advancement. Adjuncting pays less than minimum wage. Now I do these totally skill-free jobs. This morning I broke down a stage, some lights, and a PA and loaded a truck. I really enjoy not investing my own creative energy into making money. It’s just a separate thing now. But when I had to stop doing the press and when I quit teaching, I also felt burnt out on trying to write books. I published four books of my own, and afterwards, I was like, who cares? The cost-benefit ratio of how much work it takes for me to write a book . . . you don’t get that energy back the way you do in playing music, receiving energy back from the audience.

Creatively, I like to let things emerge. I wouldn’t know how to write a song if somebody told me, “Sit down and write a song.” What I can do, and what I can’t help but do, is sit down and create new systems all the time that songs emerge from. I’ve been thinking about my writing in the same way. My first book, The Karaoke Singer’s Guide to Self-Defense, I was one hundred pages in before I realized it was a novel. I think I just in the last couple of months have a new idea for a book emerging. It’s been seven years since I’ve thought about writing a book. It feels good, and I don’t care if it takes me the rest of my life, and I don’t care if anybody ever sees it. But it feels good to have it slowly coming into focus.

JC: I’ve played a lot of music too, though not to the extent that you have, and it does offer very different pleasures from writing. For me, writing is about that solitary, honed-in kind of trance, having something to do every morning. That diligent work part of it. And then actually publishing the thing is a letdown. Music was always the complete opposite of that. Not much solitary time in the crafting of songs, but when you get to play them in front of people or the record comes out and people get to experience them, that’s the best part.

TK: There are definitely different modes. My last book got published at 80,000 words, but its first draft was 210,000 words. I always make things way too much, way too long. Jenny and I are finishing our new record, and we’re one mixing day from being done with it, and I know it’s twenty minutes too long. I’ve always written too much and cut away. There’s a jolt of energy in those fractures, and that’s what I respond to when I’m reading. It’s like that in the Julián Herbert book, or in Voice of the Fish.

JC: A long time ago I took a class from Richard Ford, and he was talking about that Denis Johnson book Jesus’ Son. He said that whenever the stories would shift in the middle and jump to something else, when you cram those things together and force an abrupt turn, it creates a spark that makes the rest of the story shake.

TK: That’s a good way to put it. The thing about Jesus’ Son is that the sloppiness of it was essential. Like this would be an easy book to clean up, but if one did so, you would lose the charge. It requires those scars.

JC: It’s a very controlled out-of-control thing. It makes me think of what Garielle Lutz does with sentences, the energy they gather in the friction between lines.

TK: Yes! That’s the thing they have in common. Maybe somebody like Philip K. Dick would be the exact opposite, in terms of like, did anyone reread this? Every sentence sucks, but somehow the book is amazing. I love and appreciate both of those things. And then there’s something like Robert Coover, specifically Gerald’s Party. It’s a tightly woven thing that’s made to seem loose.

Every day I go to the gym, I take a long walk, I work my no-skill jobs, then I transition into getting stoned and making things. In that time, I listen to a lot of audio books. Nonfiction, books on aesthetics, art theory kind of stuff. When Jenny and I travel, we listen to Steinbeck, Murakami, Hemingway. Classic novels are good for driving, art theory for my personal walks. I’m very tuned in to reading different kinds of books in different circumstances.

JC: What kind of art theory?

TK: I’ve been relistening to this book on Japanese aesthetics called In Praise of Shadows by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki. Wabi-sabi stuff. It’s all about the history of Japanese aesthetics having to do with how the light reflects off paper walls pre-electricity, and kabuki theater and the makeup compared to their skin tone, and the cracks in the teacups. It’s all about leaving things a little sloppy. I’ve also been listening to one three-minute chapter every couple of days of the Rick Rubin book The Creative Act, taking it almost as a fortune cookie. Okay, what’s the section going to be today, and how will that inform my next decision? I do a lot of surrendering to everything. I’m not much of one for imposing my will on things. I find this to be a simpler way for me, day to day.

JC: I was ready to call bullshit on that Rick Rubin book, but then I read it and I was like, no this is totally good advice.

TK: I think it’s great. It’s really funny that a lot of people are calling bullshit on it. I mean, it’s not anything I haven’t read or heard a million times, but if you’re deeply invested in your craft, you’re going to come up against these ideas over and over. He did a great job of putting them together.

JC: Anything else you want to touch on before we head out?

TK: I feel like there are a million books I’m being disrespectful toward for not mentioning. I read the book Matisse and Picasso by Jack Flam. It was just great. Like everyone, I’ve had moments that were like, holy shit, Matisse, and holy shit, Picasso. But it never occurred to me to think of them together like that. I’ve really enjoyed books that the presses the Disinformation Company and RE/Search put out. They do these punk-adjacent and early industrial anthologies. I’m old enough that there are these Timothy Leary and Robert Anton Wilson pothead philosopher books that were huge to me as a kid, and I still love reading that shit. And altering your consciousness works! It gives you fresh eyes on the world. I’ve really enjoyed my time reading Alain Robbe-Grillet, even though it’s the most boring shit in the world, but it did the same thing in that it gave me a charge and added a new filter on my senses. More than anything, I’m a big fan of not distinguishing between highbrow and lowbrow. I like to take it all in.

JC: Well, you know David Markson wrote detective books too.

TK: I love Charles Willeford. Miami Blues? That shit rules. Honestly, when I stopped teaching and stopped editing, I just trusted NYRB Classics. I would just pick up whatever they put out. Do you know A High Wind in Jamaica by Richard Hughes? I fucking love that book. It just pulls you along so much. And Warlock by Oakley Hall? I love that book too. I’ve read it several times now. When I was doing the press, I tried to reissue The Downhill Racers by Oakley Hall. They made a movie out of that one, with Robert Redford and Gene Hackman. I knew the movie first. I loved Warlock so much and I was like, what else did this guy write? And then I saw that The Downhill Racers was out of print, and I remembered the movie. It’s very fragmented, like Point Blank with Lee Marvin. Anyway, I tried to put that out, but it didn’t work. Great book though.

Jimmy Cajoleas was born in Jackson, Mississippi. He lives in New York.