The Inexorable Logic of the Witch Hunt | Eduardo Sangarcía’s The Trial of Anna Thalberg

Reviews

By Kat Solomon

In the 2016 presidential election, Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton appeared in multiple social media memes depicted as a witch; some of her political opponents even dubbed her “the Wicked Witch of the Left.” Predictably, when Kamala Harris ran in 2024, she also was accused of “witchcraft.” Meanwhile, Donald Trump, on multiple occasions during his first term in office, alleged that his enemies were engaging in “witch hunts” against him. During the Joe Biden administration, some Democrats likewise argued that the prosecution of the president’s son, Hunter, was a “witch hunt.” Accusing your enemies of being witches—especially if they are women—is a tried-and-true political strategy, especially on the right. Meanwhile, both sides are quite comfortable invoking the idea of the “witch hunt” to paint themselves as victims of persecution; to invoke the phrase is to imply that there is no basis in fact to the accusations that have been made against them. In twenty-first-century America, witches and witch hunts seem to have been reduced to pure symbolism, rendered into useful rhetorical devices. Is it even possible for us to imagine our way into the minds of those early modern–era people who believed in dark magic and executed thousands of women for the crime of witchcraft?

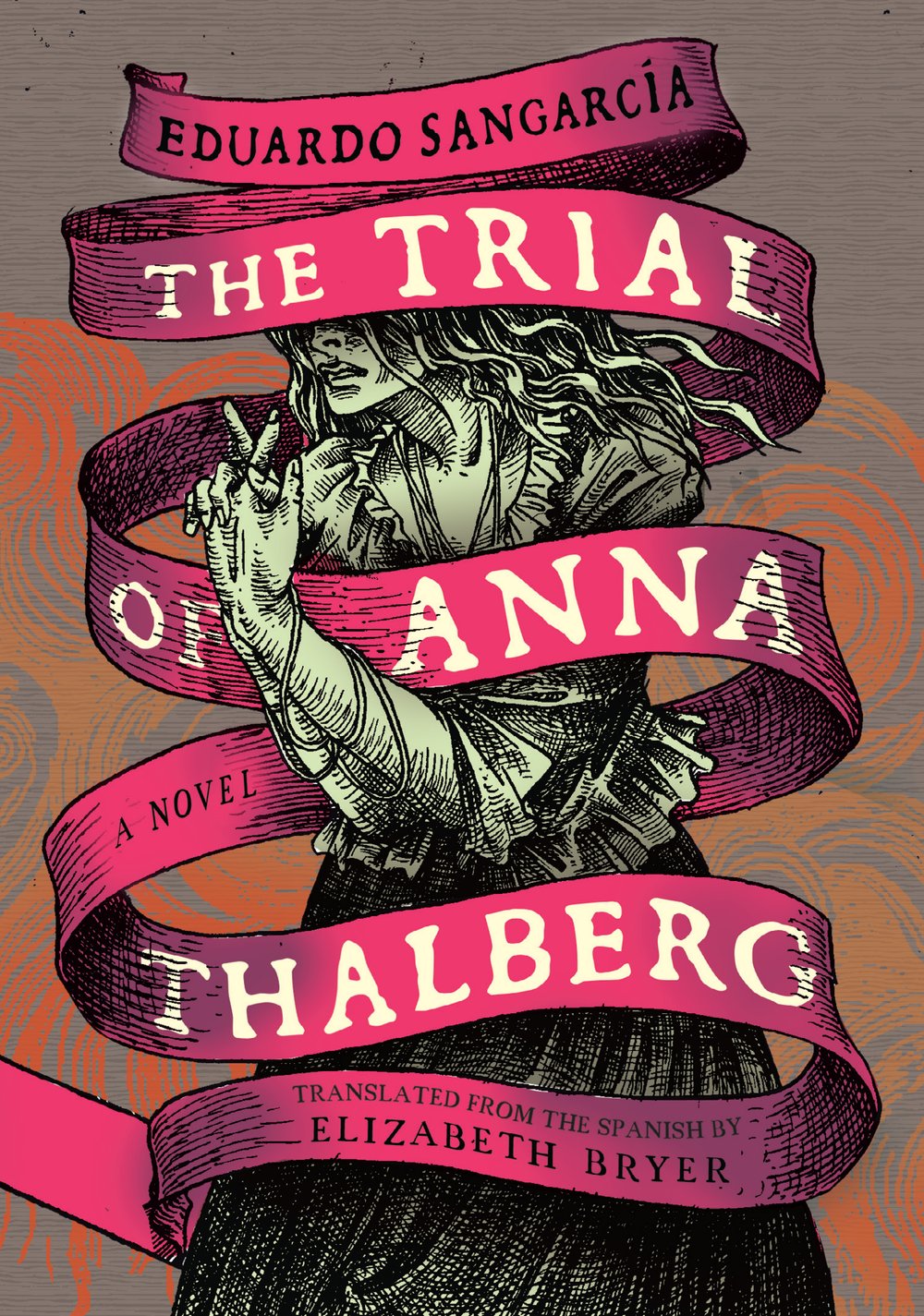

In his debut novel The Trial of Anna Thalberg (2024, translated by Elizabeth Bryer), the Mexican writer Eduardo Sangarcía succeeds in reembodying the term witch hunt by reminding us that the witch trials were, first and foremost, assaults on the bodies of real, living women. Set in the Holy Roman Empire during the Reformation, the titular character, a poor peasant, is cooking a meager dinner in a pot over a fire when she is abruptly dragged from her home, thrown in the back of a horse-drawn cart, and transported to the nearest town to stand trial on charges of witchcraft. Anna has been accused by a jealous neighbor of attending a witch’s sabbath, where she supposedly copulated with the devil, but her real “crimes” are more mundane: she is an outsider in the village where she has settled with her hapless husband, Klaus; she has red hair; and she is attractive enough to have drawn admiring looks from other men in the village, including the accuser’s husband. The reader senses that Anna is doomed from the first page to a painful death, an understanding that infuses this short novel with a kind of propulsive dread and terror, making it a hard book to put down but also sometimes a difficult one to pick up.

Anna Thalberg won the 2020 Mauricio Achar Award in Mexico, whose judges included Fernanda Melchor and Cristina Rivera Garza. Melchor’s 2017 novel, Hurricane Season, centers on the murder of a local “witch” in contemporary Mexico. Garza’s Liliana’s Invincible Summer, a National Book Award finalist and winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Memoir, is about her sister’s murder more than twenty years before at the hands of an ex-boyfriend. Garza has written that until recently, “feminism remained the f-word of Mexican vocabularies,” even as violence against women in Mexico has skyrocketed, beginning with the disappearance of hundreds of girls and women in Ciudad Juárez in the 1990s. This violence, directed at girls and women because of their gender, has led to the coining of the phrase el feminicidio (“femicide”), which officially entered the Mexican Federal Penal Code in 2012.

Sangarcía’s novel casts Anna’s trial and execution as an instance of femicide avant la lettre. The examiner Vogel is given to misogynistic musings such as “Woman is a cathedral constructed over a cesspool, a palace whose gardens and fountains all lead to the same hell.” When Anna proclaims her innocence, Vogel sends her to the torture chamber, where, upon seeing “the blood and shit emanating from the floor and walls” and the torture instruments, she faints. I admit I had to take a few breaks from the book at this point, not because the novel indulges in overly lurid detail or “torture porn,” but because I had been so effectively drawn in to Anna’s world that I felt caught in the inexorable logic of the witch hunt. The more Anna proclaims her innocence, the more her tormentors are convinced of her guilt; once accused, she is doomed. This is the stranglehold of the patriarchy, or what Garza has dubbed “the femicide machine”—still recognizable, apparently, across the space of five hundred years.

Sangarcía achieves this intense emotional effect through a polyphonic approach to perspective, moving fluidly through the minds of his different characters. Stylistically, the novel is “experimental,” eschewing punctuation such as periods in favor of a series of run-on sentences that propel the reader along. Some sections employ different fonts and spacing to signal these changes in point of view. This risks making the novel sound more intimidating than it is, however; the underlying story is easy enough to follow once the reader catches on to the rhythms of Sangarcía’s prose, skillfully conveyed in Elizabeth Bryer’s translation.

Sangarcía’s fluid use of perspective proves particularly effective at helping to bridge the distance between the mindset of the contemporary reader and the book’s sixteenth-century characters. Upon first hearing that Anna has been accused, Klaus sets out the same night to walk to Würzburg, taking a shortcut through the forest. In the darkness, he fears the presence of witches, werewolves, and the devil. The next morning in front of the examiner, he finds himself speechless, his empty stomach growling. Helpless in the face of his wife’s suffering, he remains tormented by a wild hunger that he attributes to a curse he must have contracted that night in the forest. He finds himself attacking and eating wild chickens, consuming them raw, and later plunges his hands into the entrails of fresh-killed game. Reduced to a feral creature by the extremity of his circumstances, Klaus understands his psychological disintegration in the only terms he has at his disposal: as the result of witchcraft.

Faith is the motivating force for several of those who work in the witch tower. The executioner himself asks “the angels and saints that his work might be agreeable to God” before he begins to torture Anna. Another member of the Inquisitional squad is a kindly priest who also believes he is doing God’s work, ensuring the salvation of Anna’s soul through the torment and purification of her mortal body. The sense of righteousness with which these men set themselves to the work of procuring a confession from an innocent woman is perhaps one of the most disquieting aspects of the book.

If there is a hero in the novel other than Anna, it is Father Friedrich, the village priest from Eisingen, who goes to great lengths to try to secure Anna’s release and is almost successful. In a standoff with the examiner Vogel, Father Friedrich argues that Anna’s innocence is apparent, that her poverty alone proves she can have had no dealings with the devil (believed to reward his servants with riches), and that “none of it made the least bit of sense, none of it”:

Vogel declared that no moderately educated person truly believed in it [witchcraft], that at any rate the credulous one was Friedrich himself, for believing that everyone else believed when no one truly did, not those who accused, nor those who judged, nor those who executed, no one believed that those things in fact happened, aside perhaps from one fool or other, who failed to see that all of it always served other ends

But he need not be confused, nor for that would he release the peasant woman, she was condemned because no one who went into the tower left it except to meet their end on the bonfire, just as would happen to her, her confession would be enough, and of course she would confess because they always did, always

In fact, Vogel is the only character in the book who does not believe in the existence of witchcraft, his clear-sighted cynicism marking him as a true villain. He knows that “pain and the fear of pain were his instruments, they had permitted him to keep the peasants in check so they would not rebel against the bishopric again.” Amid the rise of Lutheranism and armed peasant rebellions, here the pageantry of the witch hunts serves to reinforce the power of the church—not to mention Vogel’s own privileged place within that system. “I knew not evil until the examiner crossed my path,” Anna says. This may be the one place where it feels as if the hand of the author is weighting the scale, nodding toward our contemporary understanding, but amid the bleakness of Anna’s fate, her moral clarity is a welcome point of light.

In spite of the inevitability of its ending, The Trial of Anna Thalberg nevertheless contains some surprises along the way. Anna proves more strong-willed than any of her tormentors expect and even achieves a form of revenge from beyond the grave. Witch hunts, Sangarcía suggests, have a way of turning against the accusers; once the link between justice and truth is severed, anyone is fair game. Ultimately, this novel reminds us that the witch hunts have never really gone away.

Kat Solomon is a writer living in the Boston area. Her reviews and criticism have appeared in Chicago Review of Books and on the Ploughshares blog. Her short fiction has been selected for Best Small Fictions 2022 and has been longlisted for The Wigleaf Top 50.

More Reviews