The Kinetic Spell of Arthur Russell

Reviews

By Sam Hockley-Smith

Page 122: A vertical photograph of Arthur Russell and Tom Lee. You notice their faces first. Russell’s eyes are heavy lidded, sunk deep under the shelf of a forehead that made him look like he was perpetually halfway through thinking toward an epiphany. Lee is in the foreground, grinning up at the ceiling, blissed out. It’s all there—Lee’s unabashed happiness, Russell’s reserved, cautious love. Then the image opens up a bit more and you see it. Russell has placed his hand tenderly on Lee’s chest so lightly it’s almost hovering. It looks compulsive. Natural. Like maybe Lee didn’t even register its presence but knew it was there all the same. Below the image is a single line of text: “Peter Gordon: ‘Tom and Arthur had a beautiful connection.’”

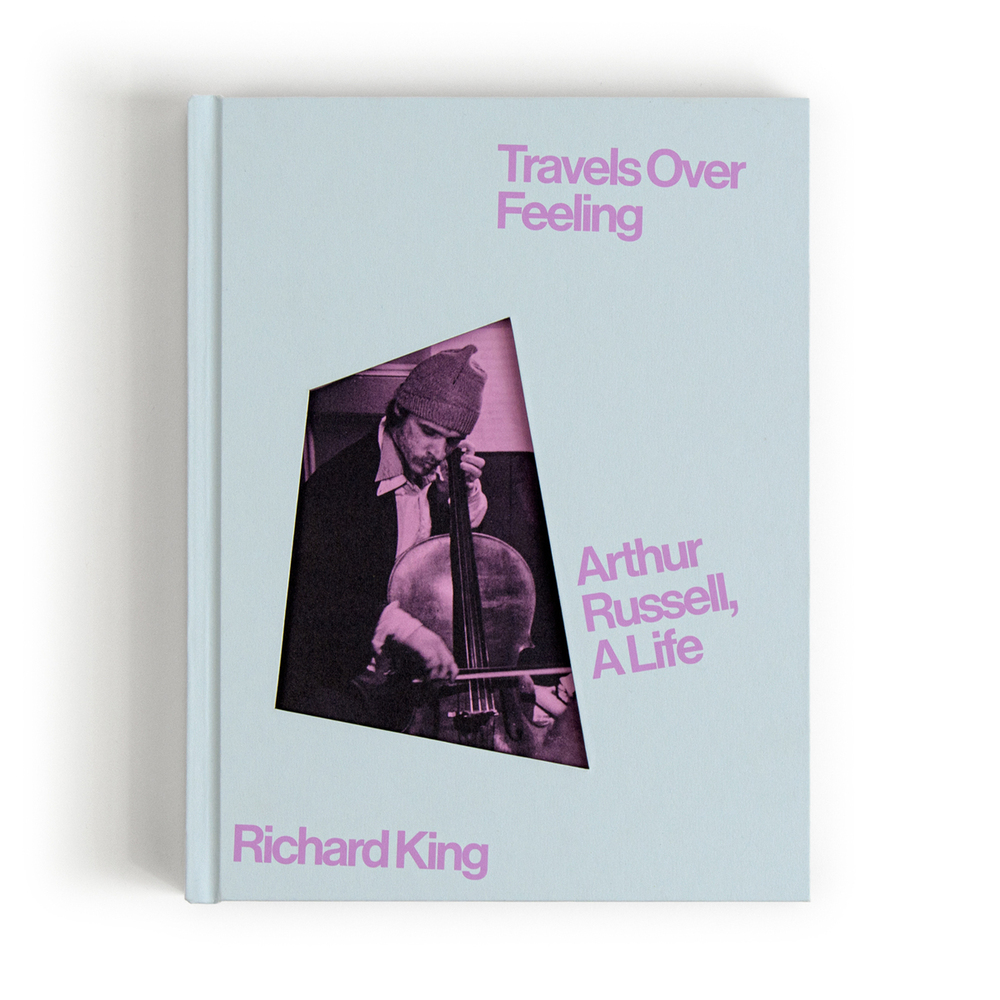

There is an ocean of meaning in the photograph, lent additional weight by how it is isolated and carefully placed within the pages of Richard King’s Travels Over Feeling: Arthur Russell, a Life, a hybrid oral history coffee-table book about the life of New York avant-garde polymath musician and artist Arthur Russell. Though King’s book is not the first comprehensive document of Arthur Russell’s devastatingly short life—he died of AIDS in 1992—it is a sorely needed publication that pulls archival photographs, images, letters, record sleeves, notation, postcards, and other missives from the New York Public Library’s Arthur Russell archives.

In his intro, King taps directly into the magic of Arthur Russell’s music and how, for so long, it existed like a whisper. Russell’s music took on a mystical quality in record stores, where clerks would mete out recommendations that transmuted into personal lodestones for those willing to take a risk on a record they’d never heard. Sure, plenty of music feels magical the first time we hear it, but does any music feel more magical than the music of Arthur Russell that first time we hear it? It sounds like a secret, and it stays a secret even as the music itself changes the way we think of our own lives. King is a unique authority on this aspect of Russell’s biography—he was one of the aforementioned record store clerks whose whole world was blown apart by the discovery of Russell, and who then recommended him to others—and his recounting is a glimpse into a pre-internet era of musical fandom. He writes, “It took several days and the usual forensic examination of writer and production credits before I was able to make the connection between ‘Go Bang!’ and ‘In the Light of the Miracle.’ I recognized a similar energy in both pieces: an invitation that called for a physical response rather than a definition from the listener, whom Arthur Russell appeared to have the gift of placing under a kinetic spell.”

That last bit—“appeared to have the gift of placing under a kinetic spell”—is a perfect way to describe the experience of tuning into the music of Arthur Russell, whose voice sounds honey-thick, round, and warm, like it is cocooned in his throat, halfway between a mumble and a daydream. Whatever mode he’s working in, the uniting factor for the listener is an implied invitation. Russell is inviting us into his world. Other people will be there with us. They’ve been there before and they’ll be there later, too, but it never quite feels like that. Every Arthur Russell song sounds like he’s speaking to only the individual. In his landscape, the rest of the world falls away. For just a few minutes, we can almost get to his core, almost understand who he really is and what he was forever trying to do. This is the gift he’s left behind.

As listeners, we are constantly reckoning with Russell’s body of work, partially because—and we are just unfathomably lucky to get to experience this—Tom Lee has kept his archive alive and organized, and Audika Records regularly resurfaces entire unreleased albums, pristine live recordings, and other digital ephemera that further cement Russell’s legacy as an omnivorous artist, more interested in exploring the contours of music itself than ever releasing a definitive statement (though there are a few albums of his that have become definitive posthumously). Put another way, if you were to ask any Arthur Russell fan where to start with his music, they’d first have to ask a question in return: “What kind of music do you generally like?”

Arthur Russell made everything: hypnotic disco, plaintive folk-country, chaotic noise clatter, impossibly gorgeous cello murmurs . . . who knows what will be unearthed in the coming years. It almost doesn’t matter. Russell genre-hopped, but everything sounded like it could only come from him. He was his own genre. We listen to Arthur Russell not because he sounds sort of like other things, but because he sounds like himself and himself only. Eventually, though, the treasure trove of recordings will run out. Instead of putting us on to Arthur Russell, the next generation of record store completists will talk about how they have every Arthur Russell recording. The picture of Russell will be a bit more filled in, but some mysteries will remain forever, true understanding just slightly out of reach.

We will, at least, still have Travels Over Feeling to accompany Russell’s increasingly sacred recordings, which sometimes feel like our strongest tether to an era of New York art-making that is more fanciful and impossible with every passing day. Travels Over Feeling is powerful in that sense. It’s a document of what it means to really, truly be an artist. It’s apparent in almost every photo in the book, every line of text, every scan of a letter or note from the archive. In most photos, Russell is in his head, practicing his cello in nature, picking up field recordings on the beach, jotting notes down, capturing half-formed ideas that would later explode into joyfully transcendent music . . . he’s always halfway elsewhere, in the moment long enough to pick up inspiration to incorporate into the next thing.

In addition to offering a treasure trove of images and insight into the life and work of Russell, the book also demonstrates a mastery of the oral history form. King doesn’t lean too much on any one perspective. He manages to cover key moments from Russell’s life while uncovering new angles on it from those who were there with him. He captures crucial insight into Russell’s history, relationships, art, and the fertile period of creativity in New York in the late 1970s with quotes that are never shaggy and overlong. Here’s Peter Gordon: “Everything was very local between Fourteenth Street and Houston, between Bowery East and Avenue B. This was right before SoHo became SoHo. It was empty at night. You could walk down the street and not see a person anywhere, but you could hear Ornette Coleman coming out of the window of his loft on Prince Street.” You can almost see it—empty New York, eerily quiet except for the skronk of Coleman’s saxophone echoing across looming buildings lit only by the sporadic placement of streetlamps.

Later, Russell’s sister Kate describes his nonstop work ethic: “Arthur always had his notepaper and his sheaf of papers. I was blown away reading his lyrics, the way he put words together. The notebook that he was always working on would be in his pocket. He would send shirts to my sister and she would sew pockets on them so he could store manuscripts and paper and notebooks in there. When he was with us, he would be quiet and at the side and if we said something that wasn’t quite right he would disappear into his work, get up and walk away and go back to his room and we would have to draw him out.” By this point in the book, we’ve learned that the default mode for the Russell family when it came to Arthur’s work was basically perplexed support. They didn’t quite understand what he was doing or why, but they understood that it was important to him. Russell’s sister sewing extra pockets into his shirts so he could better hold his notes is one of many indelible moments in the book—we read that and we get a whole new layer of understanding of Russell, of art, of the unending drive to create.

As Russell nears death, the cadence of the text slows and blooms—opening to longer thoughts from everyone who knew him, and ending with a multipage account of his death from Tom Lee. This textual contrast exemplifies the urgency and restlessness of Russell’s tragically short life: he could not know that he would die young, but he created like there could never be enough time to do it all. It’s awful to imagine the stuff we’ll never get to hear, but it’s wonderful that we even got what we got.

The second to last image in the book is of Russell in silhouette, backlit by the high sun. We can’t discern a single feature—his neck sort of just disappears into his hair in a way that makes it hard to tell which way he’s even facing—but it doesn’t matter. There’s a sense of radiant calm emanating from the image. It’s the kind of calm that people only achieve once they’ve glimpsed true peace.

The final image in the book does not include Russell at all. It’s a photo of some large brown rocks jutting up against the shore, waves crashing and spraying white against the blue of the sky. It’s Baker Island, Maine, where Lee and the rest of Russell’s family scattered his ashes. They’d all had a picnic there before, and remembered it fondly. It made sense to go back. Lee recounts throwing Russell’s ashes into the Atlantic, wondering if they might eventually reach New York. Surely they would. Maybe they’re already there. Maybe they were always there.

Sam Hockley-Smith is a writer, editor, and radio host based in Los Angeles. His work has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, the FADER, Pitchfork, NPR, SSENSE, Bandcamp, Vulture, and more. His radio show, New Environments, airs monthly on Dublab. He spends his spare time reading.

More Reviews