The Magic Trick They Will Never Get Sick of Performing

Reviews

By Burke Nixon

Last January, I broke my hand punching a wall during a pickup basketball game. I’m a grown man, over forty. I don’t punch things, living or inanimate. But I was amped up, and I got fouled on a drive by a basketball buddy of mine who’s known for his frequent, gratuitous fouling and who’d been talking a lot of smack. I missed the layup and stumbled toward the cushioned part of the gym wall behind the basket. When I came to a stop, I paused for a split second—oh, to regain possession of that moment—then reared back and punched the wall as hard as I could. The cushion was much firmer than I expected. I knew right away that I’d done something very, very stupid.

I wore a cast for six weeks, during which time I had to explain to many people—friends, strangers, coworkers, small children—that I’d incurred a “boxer’s fracture” by punching a wall during a pickup basketball game. Some laughed, which struck me as appropriate. No one was impressed. Many people shook their heads, not just at the stupid and shameful act of wall-punching itself but also at the fact that I’d done this, at my age, over a pickup basketball game. Multiple healthcare professionals informed me that they saw this injury more commonly among adolescent boys.

But one of my closest friends in the world—RH, my teammate in both middle and high school before he went on to varsity and I went on to hang out at Blockbuster Music—had a different response from everyone else. “Man, you shouldn’t feel bad,” he said, when I called him up to tell him what happened. “You punched the cushion behind the basket. That’s what we do.”

RH doesn’t play basketball anymore. (Knee problems.) Even in our adolescence, I don’t recall him punching any walls, cushioned or otherwise. But that wasn’t his point. His point was that we’ve always been part of the tribe of basketball obsessives who gets super-competitive even in pickup games. As members of that tribe, we sometimes express our competitiveness by doing things like punching the cushion behind the basket. This is who we are.

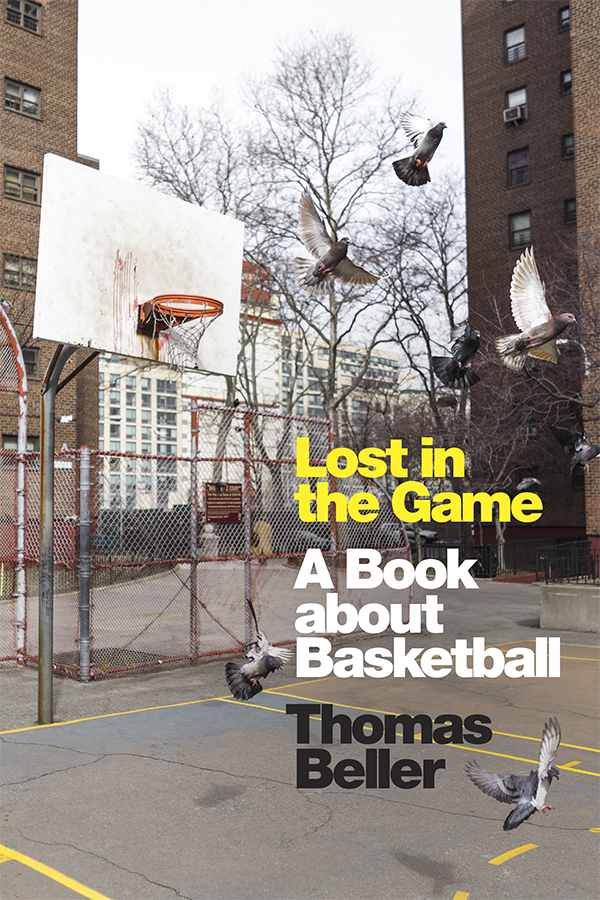

Thomas Beller would understand this because he’s a member of the same tribe. In fact, based on the contents of his new book, Lost in the Game: A Book About Basketball (Duke University Press), it’s clear that Beller is an even more obsessive member of the tribe than I am. His book is, among other things, an honest and entertaining self-portrait of one compulsive participant in the “cult of basketball,” the kind of grown-man hooper who anxiously awaits the moment each afternoon when a playground game becomes a possibility and who still gets into shouting matches at the New York City court where he started playing in 1977.

More than any writer I’ve ever read, Beller captures the joy, pressure, and almost narcotic escape that pickup basketball offers. He’s interested in basketball as a secret alternate life, “a refuge, a state of grace in the present moment, a thing in which to get lost.” He also captures the strangely high emotional stakes of pickup ball, priding himself on being the type of player who ratchets up the tension through his verbal and physical contributions to the game:

For a long time now, that has been my thing—to be intense, to play hard, to exhibit a certain smug satisfaction at hitting shots, to want to win, to relish nifty passes, to clap and congratulate my teammates, to be loud, to be in your face, to stir the pot so that the people I’m playing against feel annoyed and insulted, so they try harder. Afterward, everyone seems to feel the game has been better for it.

On one hand, yes, these sentences describe the most annoying guy at your local YMCA. On the other hand, Beller’s self-description makes me want to go find a court and play right this second. He manages to articulate the special communal intensity of a great pickup game, when every tough shot and nice pass and shout of encouragement (or antagonism) feels significant, even if the proceedings would seem utterly meaningless to an outsider.

Although Beller played basketball in high school and college (at Vassar)—“I was a project,” he says—he favors the street game. Currently an English professor at Tulane and the author of several works of fiction and literary nonfiction, Beller grew up in New York and returns often in the summers, seeking games on courts throughout the city, but especially at Riverside Park, the place where he first discovered “the city game” as a very tall (by non-NBA standards) and not particularly athletic young man. He loves the unpredictability, improvisation, and psychic warfare of the playground game, particularly in the summer, when “the city’s fried asphalt courts give off a kind of energy”:

You have to stay loose. You’re up against kids and geezers, pot smokers, drinkers, fitness freaks, guys who like to spit a lot, and lunatic ballers, many of whom look totally undistinguished as athletes until they start tossing the ball up and it goes into the hoop again and again and again, and you realize that this is it, their true talent, the magic trick they will never get sick of performing.

In his sharp-eyed and thoughtful style, Beller captures the conflicts and characters of the playground game, offering vignettes that range from the hilarious to the heartbreaking. At one point, he’s repeatedly poked in the face by an opponent whose nickname is Homicide. Elsewhere, he learns that one of the regulars at his local court, a stout and imperious trash-talker named Rich, has been murdered during his night job as a tollbooth worker. Remembering Rich, Beller is reminded that “on the basketball court, you can know someone intimately and not know him at all.”

The book isn’t just about the joys and sorrows of playground basketball, however. A passionate fan and entertaining observer of the NBA, Beller also offers what he describes as “close reads” of some of the game’s most fascinating players. And so we get essays analyzing James Harden’s “transcendent” step back move and Damien Lillard’s legendary game-winner against the Thunder in the 2019 playoffs, not to mention a lengthy essay—one of the book’s highlights—reflecting on the unique personality and play of Nikola Jokic. This book is also the only place where you can read a thoughtful reassessment of Latrell Sprewell alongside a surprisingly moving essay about a wordless airport encounter with someone who may or may not be Bol Bol.

So yes: Lost in the Game is an essay collection, although neither the book’s front nor back cover is willing to acknowledge this uncommercial fact. Many of the essays were originally published on the New Yorker’s website, while a few others were published in the digital editions of other literary magazines (n+1, Paris Review, etc.). A couple of others were published in Beller’s previous book of essays, How to Be a Man: Scenes from a Protracted Boyhood. This leads me, unfortunately, to Lost in the Game’s biggest flaw. It’s a very repetitive book. The same anecdotes and observations often appear in multiple essays without any acknowledgement that we’ve read them before. For example, an apocryphal story about James Naismith and a little boy appears in three different chapters—in a book that’s barely over two hundred pages. As someone who loves to tell the same anecdotes over and over, I can certainly relate to Beller, but all the repetition made me suspect that reading this book from beginning to end isn’t the ideal way to enjoy it. Better to pick a random chapter and skip around from there.

That said, if you’re a fan of basketball, you will enjoy this book. And if you happen to belong, as I do, to that odd slice of Venn diagram consisting of people who appreciate a great sentence just as much as they appreciate a nice bounce pass in traffic, you’ll love these essays even more. Beller’s linguistic highlight reel still lingers in my mind, from his description of Harden’s “rabbinical beard” to “the basketball prodigy look” of a group of teenage AAU players in socks and athletic sandals. In a parenthetical aside, Beller describes getting dunked on at a NYC playground by a fourteen year-old Joakim Noah, “a human pencil with an Afro smushed under a backwards baseball cap.” In another essay, he refers to himself as a “basketball poster boy,” in the sense that he’s the one on the playground who’s always getting posterized. For years I’ve wanted to read a hoops version of George Plimpton’s hilarious and wonderfully written works of participatory journalism about boxing, baseball, and football. Lost in the Game is, finally, that book. (By the way, presses should put out more collections like this one. Give me books about basketball by Damon Young! Jess Walter! Jay Kaspian Kang! Kiese Laymon!)

After breaking my hand on that cushion, I ended up having to sit out my regular pickup game for more than three months. (“What is it about self-inflicted wounds and their capacity to disorient you?” Beller asks, a question that still haunts me.) Those three months came not long after the eighteen or so pandemic months when the gyms were closed and the rims had been removed from the playgrounds. During all that time, I tried not to think about basketball. When I finally came back to the court, though, I remembered what I was missing: the fellowship and friction, the laughter and frustration, the exertion and elation, the sense of being fully occupied in the present moment. The brief but deeply enjoyable satisfaction of finding the open man or stealing a lazy pass or seeing your shot fall through the net. It’s hard to explain why it all means so much to me. Luckily, now I have Beller’s book.

Burke Nixon lives in Houston and teaches at Rice University. His NBA blog, Dear Dikembe, was read by tens of readers weekly during the lockout-shortened season of 2011-2012.

More Reviews