The Mind of All of Us

Reviews

By Wilson McBee

“On day one, I will terminate every open border of the Biden administration, and we will begin the largest domestic deportation operation in American history”

—Donald Trump, Conway, South Carolina, February 10, 2024

Out of either a desire to maintain sanity or a belief that the institutions of American government will always stand up to outright tyranny, one wants to avoid fixating upon every ridiculous dictatorial threat thrown out by the former president in his rambling, often incoherent campaign rallies. The idea that on January 20, 2025, government-sanctioned snatch squads will begin roving through the country, disappearing anyone who fails to fit their definition of “American citizen,” is truly the stuff of nightmares. Dwelling on the image is probably not healthy—but ignoring it is much more dangerous. Setting aside the perennial argument about whether Trump is a fascist with a capital F or the latest in a long line of American “far-right populists,” we do know that mass deportations have a history in this country. In 1954, for example, the US government claimed to have abducted and repatriated some 1.1 million Mexican immigrants (the actual number could have been much smaller). The Obama administration was responsible for 3 million deportations. Could it happen here? It already has.

Mauro Javier Cárdenas’s new novel, American Abductions, takes the deportation threats of Trump and others seriously, if not literally, as the saying goes. The novel imagines a near future in which groups of badgeless goons use surveillance technology to abduct and deport Latin Americans, regardless of citizenship status. One of those abductees, the Colombian American writer Antonio José Rodriguez, is the book’s central character. Years after being plucked from his life in San Francisco and deported to Bogotá, Antonio suffers a debilitating heart attack. His daughter Eva, an installation artist who has followed him to Colombia, informs her sister Ada, an architect who has remained in the States, of the situation and begs Ada to join her at their father’s deathbed, even though the immigration protocols make such a journey practically impossible.

Since being sent to Colombia, Antonio has been engaged in the project of interviewing other victims of the mass deportations. Antonio and his interviewees cover the pain of family separation, their broken trust in the American dream, and the psychic rupture that comes with displacement. These passages make for harrowing reading, as the speakers sift bravely through their trauma even as they know that finding closure is impossible. One interview subject, Auxilio, was kidnapped while on her way to pick up her daughter, Aura, from preschool. Preparing for this dreaded outcome, Auxilio had coached Aura to remember her aunt’s phone number, but the aunt never heard from Aura before being abducted herself. Auxilio agonizes over the separation and what led to it: “Can you imagine, as I have imagined, how Aura remembers that moment, if she can still remember that moment, the moment she forgot one number out of ten, two out of ten, because of one number I lost my mother, Aura probably says to herself.” These conversations show how the mind—wielding the weapons of guilt, regret, and speculation—can be its own torture chamber.

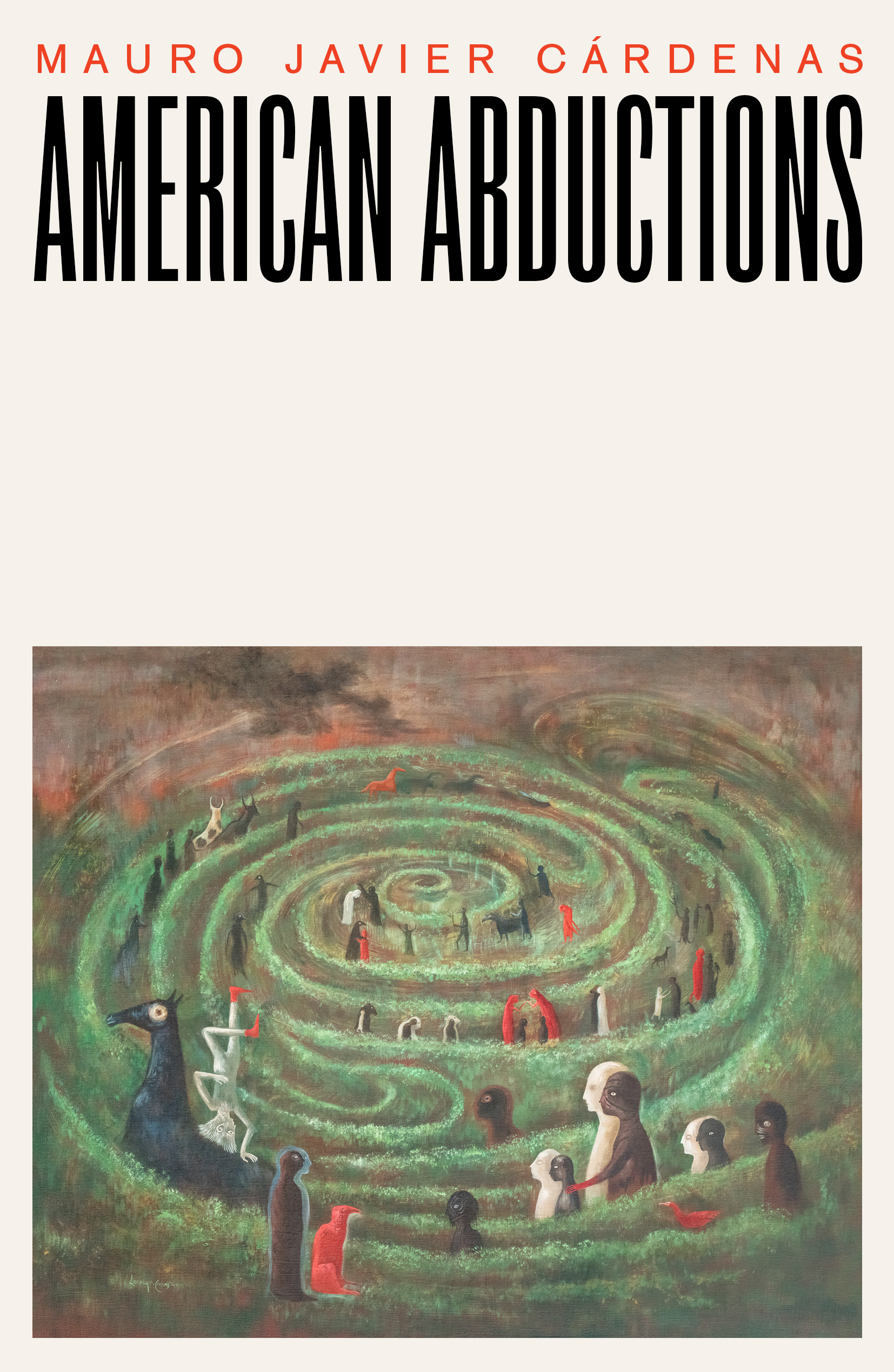

American Abductions is a sequel of sorts to Cárdenas’s previous novel, Aphasia, which also focuses on a writer named Antonio with two daughters named Eva and Ada, although some of the central plot concerns in the earlier novel, such as the relationship between Antonio and his mentally unwell sister, are absent here. Most important, American Abductions employs the same densely compacted stream-of-consciousness style, in which interwoven threads of thought vie for narrative attention. Aphasia is far from easy reading, and American Abductions is at times even tougher. Where the earlier novel derives from one principal consciousness—Antonio’s—American Abductions has multiple characters at the helm, sometimes simultaneously. In moments where Eva and Ada listen to Antonio’s interview recordings and continue the project by recording conversations of their own, the reader must confront the tangled internal and external voices of Antonio, his subject, and his daughters all at once. Intruding into the novel’s multivocal cacophony are an AI generated from the works of Leonora Carrington and Doctor Sueño, a quasi-omniscient being who offers questions, retorts, and asides.

Also as in Aphasia, Cárdenas incorporates multiple references to and discussions of his artistic touchstones, such as the writer Roberto Bolaño and the composer Olivier Messiaen; these allusions speak to the foundations of the novel’s form. But the style of American Abductions is about more than simply shooting off modernist fireworks. Cárdenas is saying something important about how trauma is shared, and mediated, across generations. Reflecting on how she wants to describe her experience, Auxilio emphasizes the way her psyche has been warped by deportation:

I thought what I should attempt to describe for you is how my mind changed after they abducted my daughter and I was deported, and I remember I imagined being part of a collective mind, the mind of all of us who have been deported and whose family members have been abducted, a mind like a sea struck by a meteor, a sea that ceases to be blue or green as it overtakes the continents, the fish turning into lizards and the lizards into birds with gills, a sea that is no longer the sea but a carnival of destruction and a cemetery and a neighborhood.

For the characters in American Abductions, pain appears as a discordant clamor, a storm in which alternative realities contend with the ugly truth of what really happened. Cárdenas’s novel shows us that reckoning with the future is just as important as reckoning with the past. Indeed, both actions require impressive feats of imagination, empathy, and courage.

Wilson McBee lives in Highland Park, Illinois, and is currently at work on a novel.

More Reviews