The Novel as Total Organism | A Conversation with Betina González

Interviews

By Heather Cleary

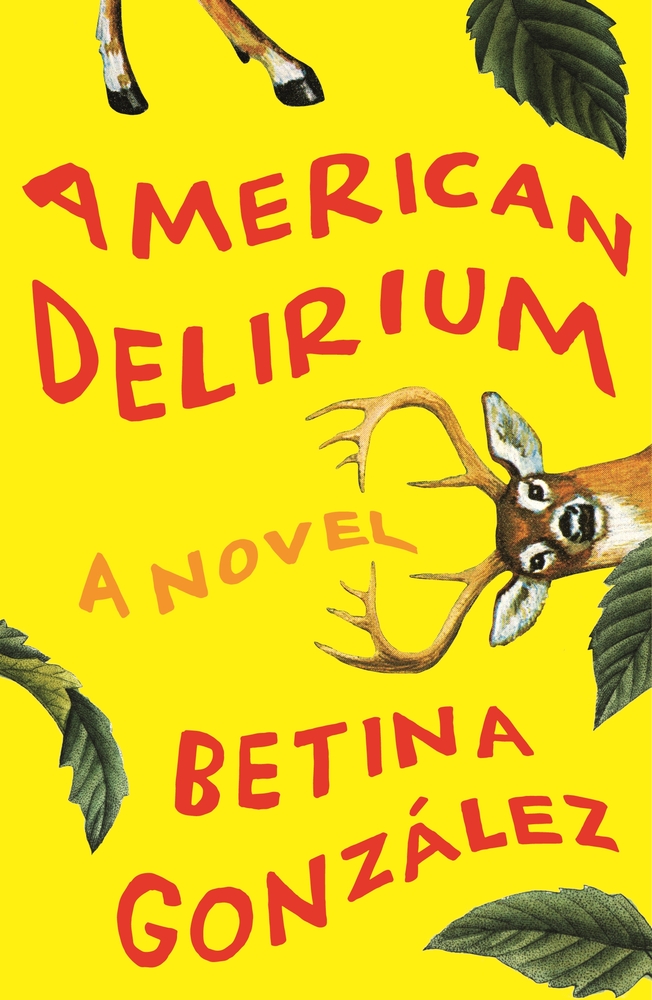

In an unnamed city somewhere in the United States, deer are leaving the woods and attacking people as they garden, shop, or jog. Meanwhile, people are leaving their homes, jobs, and children behind to go live off the grid as “dropouts.” The dystopian jolt that is Betina González’s American Delirium explores these events through three storylines, each with its own narrative voice.

The first of these storylines centers on Vik, a refugee from an island known as “the Pompeii of the Caribbean” who works as a taxidermist at the local museum of natural history. It turns out that, unbeknownst to him, a dropout has been living in his closet. Next comes Beryl, a former hippie with a turbulent past who is training local senior citizens to hunt so they can tackle the deer problem and prove that they “still have a light on upstairs.” The third storyline traces young Berenice’s quest to find an adult willing to claim her as a relative after her mother runs off; if she doesn’t, she’ll be ostracized by her classmates or sent to a government work farm for “left-behinds.” Underlying the generalized societal disintegration and connecting the lives of these three characters is a powerful hallucinogen derived from the rare albaria plant.

I’ve known Betina for more than a decade, and with every new text of hers that I read, I’m astonished all over again at her capacity for observation and—even more so—for distilling what she observes into novels, essays, and commentaries that are at once conceptually rich, emotionally resonant, and extraordinarily measured in their expression. It has been a true pleasure to work with her over these years, and a thrill to see this extraordinary novel begin to reach readers in English.

Heather Cleary: You describe some pretty wild situations in this book, but the world you create also manages to feel terribly familiar. Could you tell us a little bit about how American Delirium began to take shape in your mind?

Betina González: It is a book that had many beginnings for me. I had always been fascinated by the 60s and 70s in the USA. Those were decades of tremendous cultural change, marked by pacifism, the civil rights movement, sexual liberation, drugs, and rock and roll. I was especially fascinated with the idea of the commune and this unique era in which people thought they could create a human organization that transcended the patriarchal family. So, there was that. And then our present: how those ideals collapsed and were swallowed by capitalism. Even now, when it is so pressing to do something about global warming and to end this unsustainable greediness based on the absurd idea of constant economic growth, we see a revival of some of those ideals, but not in the same radical fashion. I have the feeling that our societies are unable to harness them into something that could be called “a movement.”

So I had this contrast, this fascination in my mind for some time until I moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. There I found a kind of atmosphere that shaped the fictional city in American Delirium. And one day I was watching the local news and saw a TV commercial for a senior home that showed a group of elders participating in different recreational activities. One of them was hunting. Being a stranger to American culture, it looked shocking to me—people at the end of their lives, who could barely walk or hold a rifle, acting as predators, going out to kill. And the idea that some of them could have been hippies in their youth crossed my mind and made me laugh because it is so often the case that when we get older we become the opposite of what we thought we were going to be. That thought gave me one of my characters, Miss Beryl. By then, I already had Vik and Berenice. That’s why I say the novel had many beginnings; it was like writing at least three novels at a time, one for each character. They lived with me for many years.

HC: I see why you include Joan Didion among the writers who shaped this project! In your answer here, and in the novel as a whole, there’s a remarkable balance between keen observation and sensitivity to the details of a vivid and visceral humanity. You also make a powerful motif out of two interrelated desires that you touch on above: reimagining the future and rewriting the past. What place do you feel these desires have in the world of this novel and in the world we currently inhabit? Did your feelings change as you wrote?

BG: First, I must say that Slouching Towards Bethlehem is among the most important readings that shaped this novel. It is a book that captures those decades, the exhilarating feeling of those liberation movements and, at the same time, their possible ephemerality. It is curious how reading shapes our writing; one never knows which book is going to be THE book that takes you to your own. Anyway, I think there is no writer like Didion. She really captures all the nuances in a story, and she’s been writing America and its contradictions for decades. She is the writer I always think about when somebody here in Argentina asks me about the USA—about what the country is really like.

As for change and desires, I belong to a generation of Latin Americans that grew up in the years of state terrorism, surrounded by the violence, the torture, and the killings that these dictatorships undertook as a massive plan to wipe out the whole previous generation. Because of that we, as youths during the 90s, felt that change or collective movements were not available to us. It was hard for us to believe in any kind of utopia. (Fortunately, we see that reborn in our younger generations. I see it in my students and it is inspiring). It took me years to realize that cynicism and irony sometimes work in favor of those oppressive regimes and of capitalism itself. To convince us that no change is possible, that there are no alternatives to the system, is the highest achievement of that ideology and of that terror. As a writer I can’t help but write about that, to address those issues.

It is true that in American Delirium there are characters who want to change the past as a way of imagining themselves as others, maybe as a way of imagining what could have been different, what kind of future may still be available in that past as “a road not taken,” but also as a way of not taking responsibility. I like to play with that idea. It is a perfect idea for speculative fiction; it’s like thinking about your life as if it were a novel. On the other hand, that idea of changing the past is disquieting in itself. It has a kind of reverse nostalgia—a nostalgia for that which never happened—that could be very dangerous. Reverse nostalgia is good for a novel, not so good for life. Or for history.

HC: This is a novel written in three voices. How would you describe each of them, and how did you go about creating these different subjectivities through the language they use?

BG: It’s hard for me to describe the voices of each story. It’s a little bit like describing music. I think so much of a narrative is in the voice, in its emotional tones and rhythms. I may have a story in my head but I don’t start writing it unless I hear the voice telling it. In this novel, there is something of the tone of the classic fairy tale in Berenice’s story, a play with variations on irony in Vik’s, and a lot of anger and humor in Beryl’s. But I would say that all these tones are encompassed in the language of the novel, which I think of as a total organism. That particular language is made up of the sound of certain English phrases I hear in my head and of my readings of American and British literature. At the same time, it is also made up of many “Spanishes”—the one I used for many years as a teacher; the one I learned in Texas; my Rioplatense; the colloquialisms and tones I acquired from friends from different Latin American countries; etc.

Your question makes me think about your work and the many exchanges we had throughout the translation process. I remember you being very meticulous about capturing that particular language. So I guess now that it’s over, I can ask you, what was the hardest thing about translating this novel for you? (Aside from my neurosis, of course.)

HC: Ha! There was no neurosis at all. Honestly, it’s been an absolute joy to work with you—on this and every text we’ve done together. I said somewhere, at some point, that the hardest translation isn’t the most experimental or the most research-intensive text, but rather when you can’t fully trust the author. When you can’t be sure if the unusual formulation (or name change, or revival from the dead) that you’re seeing on the page is an error or a deliberate choice. There was none of that confusion here—you’re so precise with your language and imagery—so instead of difficulties, what I encountered were exciting challenges. (I’m lying: there were a few difficult things, like figuring out what to call that damned turkey-adjacent bird that pops up in Lund’s 19th-century travelogue.)

One example of these good challenges was how to create the textures of the different voices while still maintaining the cohesiveness that the novel has in Spanish, what you refer to when you describe the language of the novel as “a total organism.” I remember our conversations about these inflections early on—I wanted to make sure what I was hearing in each one was aligned with your intention. Beryl’s voice is clearly differentiated from the other two, because it’s in the first person and because she’s pretty frontal in her worldview. What an absolute joy it was to step into her brashness and her vulnerability. On the other hand, Vik’s and Berenice’s narratives are written in the third person and the difference in tone between them is subtle, but it’s definitely there. Berenice’s storyline, as you say, is a bit like a fairy tale; whereas Vik’s simmers with bitterness and disillusion. His voice took me the longest to enter, because . . . well, he’s not easy to like. But there are so many layers to his character, and by the end I was finding wicked delight in inhabiting his misanthropy. (I hope I’ve regained some of my faith in humanity since then.)

Betina González is the bestselling author of several novels and short story collections, for which she has won several awards, including the prestigious Premio Tusquets. American Delirium is her first book to be published in English. González earned her MFA in bilingual creative writing at the University of Texas at El Paso and her PhD from the University of Pittsburgh. She lives in Buenos Aires and teaches at the University of Buenos Aires and New York University Buenos Aires.

Heather Cleary’s translations include Betina González’s American Delirium, Roque Larraquy’s Comemadre (nominee, National Book Award 2018), and Sergio Chejfec’s The Planets (finalist, BTBA 2013) and The Dark (nominee, National Translation Award 2014). A member of the Cedilla & Co. translation collective and a founding editor of the digital, bilingual Buenos Aires Review, she teaches at Sarah Lawrence College.

More Interviews