The Sense of Being a Boomerang

Reviews

By Caroline Tracey

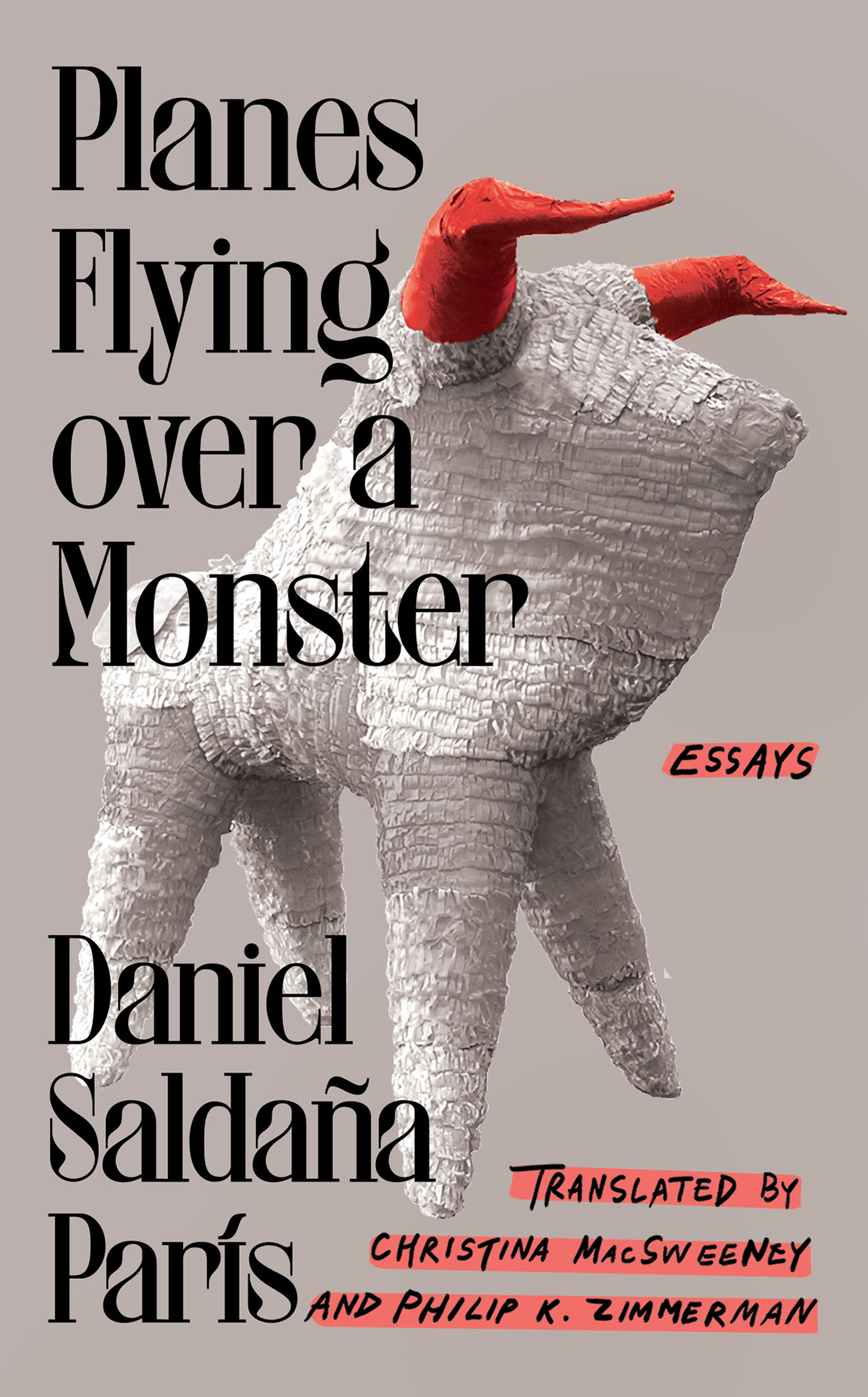

In Spanish, Daniel Saldaña París’s essay collection Aviones sobrevolando un monstruo (Anagrama, 2021)—newly translated by Christina MacSweeney and Philip K. Zimmerman as Planes Flying over a Monster (Catapult, 2024)—has two introductions. In the “Nota Preliminar,” the thirty-nine-year-old Saldaña París describes his start in the literary world: while writing reviews for the magazine where he was an intern during his undergraduate years in Spain, he developed a habit of inserting fictional elements that no one noticed. “I included a reference to a nonexistent neo-situationalist magazine that, according to my article, had recently been launched in the Madrid neighborhood of Malasaña. Later, in other reviews, I spread fresh rumors about that impassioned neo-situ splinter group.”

The second introduction is the titular essay, which in the Spanish edition follows the preliminary note. In it, Saldaña París returns to Mexico City after one of his many stints abroad, ready to lay claim to the metropolis as his home turf, even as his relationship to it remains tense: it drives him to madness, constantly pushing him away. “In the Monstrous City there always seem to be more important things to do—anything but write a book!” he decries.

Between these two calling cards, Saldaña París readies his readers geographically and stylistically for what’s to come in the collection: something like Sergio Pitol meets Daniil Kharms. While the preliminary note sets a charming, absurdist tone that signals we are going to enjoy ourselves here, “Planes Flying over a Monster” grounds the reader in the life trajectory that has inculcated in Saldaña París such creative cynicism.

The book’s essays capture moments in the life of a literary knight-errant who has traveled the world seeking the moments of absurdity in the real, and has then sutured them into meaning through writing. Quixotic in more ways than one, it’s a pleasurable journey to follow. Saldaña París sees the world from an oblique perspective, picking out its unusual, even supernatural, details. The collection mines the origins of this impulse, but also delights in the ways it enriches the world, including by occasioning misadventures.

One of the essays that best displays these efforts is “Return to Havana,” in which Saldaña París travels to Cuba, where he was conceived by young, radical parents there on a solidarity tour. (It’s only a “return” in that sense; otherwise, it’s his first time in the country.) His portrait of his parents is tender, but what’s most interesting about the essay is the unusual turn it takes toward the end, when Saldaña París turns to a completely different memory. When he was nineteen or twenty—the age at which his parents were attending meetings of leftist organizers—Saldaña París became obsessed with the Cocos Islands in the Indian Ocean and convinced a friend “to found an artistic avant-garde” headquartered there. They begin to mail quotidian objects to an address they’ve found, believing they are building an “impossible archive.”

Of course, the movement fails: the objects are returned to sender. But in the context of the essay, the two seemingly unrelated stories illuminate one another. By straying geographically and temporally, Saldaña París finds answers conceptually, understanding how the political commitments of one generation evolve in the next into another kind of vanguard, one that is quirky and artistic but equally daring in its conjuring of a different world.

He continues trying to find his avant-garde as a college student in “The Madrid Orgy,” an essay that takes the form of a relato, or tale. Saldaña París and his girlfriend were obsessed with the French theorist Georges Bataille and his book Erotism, which claims that the “potency” of the orgy is not found in its dignified aspects but in its “ill-omened” ones, “bringing frenzy in its wake and a vertiginous loss of consciousness.” (In Spanish—like the original French—the opposition between the two ideas is clearer: fasta and nefasta.) The couple decide to bring the theory to life, and offer their guests two piñatas: one fasta, one nefasta. One is filled with candy; the other, offal. When the latter breaks open, animal blood covers the apartment; the guests rush out, horrified. Saldaña París finds his girlfriend fulfilling their orgy plan by having sex with a stranger, and he flees, crushed, to a nearby gay bathhouse to give his first blowjob and find comfort with “two magical bears.”

It’s a twice-told tale, perhaps told too many times before being written down. (The tale is so well known in certain circles in Mexico City that I’ve heard people relate stories of Saldaña París telling the story.) “I won’t linger on the details here because this is a story I’ve already told too many times, egged on . . . by friends who have heard it before, and I no longer have the urge to gloat over it all,” he writes, leaving those of us who never heard it in its oral glory to use our imaginations. But the essay form offers something that the forward motion of party anecdotes can’t: writing the story down allows Saldaña París to dwell on the ways that literature and theory insert themselves into one’s life and, through doing so, to “return to a scene from the past and suddenly be able to observe it with the eyes of an onlooker.”

Another essay in which Saldaña París works his alchemy of life and literature is “Malcolm Lowry in the Supermarket,” about his childhood in the city of Cuernavaca—the setting of Lowry’s novel Under the Volcano—and the shadow of the city’s lost literary history. “I like to think of cities,” he writes, “as territories existing on a variety of planes: the historical, the real, the political, but also the fictional; to find points of coincidence between a physical topos and another, lighter, more seamless one that is not real in the same sense, but also exists.” Saldaña París’s personal and literary geography of Cuernavaca leads readers from the site of the first scene in Lowry’s novel, now bulldozed for “the meat section of Costco,” to a church whose monks, once upon a time, developed a progressive interpretation of Roman Catholicism influenced by psychoanalysis, to the iguanas of an A-list celebrity of the 1940s. Though not the flashiest essay in the book, it has one of the most intriguing mixes of setting, personal narrative, and literature, a mix that should send readers on their own quests to understand the layers that compose their own psychogeographies.

The English translation closes with “Assistants of the Sun,” about a cult that Saldaña París and his father joined during the author’s childhood. More recent than the other essays and not included in the Spanish edition, the essay feels like the book’s natural culmination, further exploring how Saldaña París’s past shaped his unusual orientation to the world and reflecting on the ways he has concluded that he hopes to see the world. “The basic idea,” he describes of one ritualistic exercise, “was to leave behind a version of ourselves that we would like to shed, and, in exchange, ask a question of the earth.” What else but that does an essayist do?

While I found this addition of the final essay admirable, I was surprised to discover that the other essays had been completely reordered for the English edition. The collection now starts off with “A Winter Underground,” which is set in Montreal as Saldaña París’s ex-wife starts a doctorate. The essay is among the book’s most memorable, following Saldaña París’s experience with opioid use and recovery, ambulating through the Narcotics Anonymous groups hidden across Montreal.

Yet for me, it is an odd choice as an opener. Starting the book with the author giving himself an enema so that he can better absorb his wife’s prescription pills via his anus feels in line with one of the unwritten rules of US publishing: start off with a bang. But Planes Flying over a Monster isn’t the kind of essay collection that derives its interest from recounting a series of increasingly shocking life events. It’s reflective and allusive; its essays don’t follow the action-based narrative structure of rising tension, climax, and resolution, but rather invest in lush exposition, meander through their events, break the fourth wall with reflections on writing, and have long tails thinking through the role of books in daily life. Even “A Winter Underground” ends not with the triumph of sobriety but with a discussion of the novels of Réjean Ducharme, “a cult idol of Quebec literature.”

In the book’s new arrangement, when we see Saldaña París as an addict, we haven’t yet heard about his childhood in Cuernavaca, his divorced leftist parents, or his decision to become a writer. It’s not even clear how we’re supposed to know that he is from Mexico (rather than, say, the Spain of the preliminary note)—unless we’ve been expected to read the encomium of the front matter. Perhaps this is an intentional change to the emotional geography that underlies the book—a shift toward cosmopolitanism in place of the sense of being a boomerang to and from Mexico City. But to me, the attempt to start off with fireworks didn’t quite work.

While the intensive intervention in the order of the book’s contents puzzled me, the lack of intervention in its sentences occasionally irked me. The stems and syntax of the original Spanish often remain in a way that makes the sentences sound more convoluted than they do in Spanish, and in turn lose some of their muscle. One moment in the preliminary note reads: “The essays in this collection are the product of an analogous process to that first review. Some were originally commissioned pieces or written to earn a more or less derisive sum, but in the multiple rewritings and rounds of corrections, they have taken on new meanings.”

To my ear, “analogous” and “derisory” feel overly Romantic; “similar” and “laughable” are right there, and they’re the words a writer working in English would have been more likely to use. Similarly, the editor in me felt an instinctive need to simplify the spliced clauses of the second sentence to “but took on new meanings during multiple rounds of revision and rewriting.” In making readers wind their way through tortuous sentences and uncommon vocabulary, I felt the translation lost more than it gained in letting them see through to the Latinate roots of the original. To me, it feels more important to match the writing’s tone and clarity.

This is, however, an aesthetic preference rather than a problem to be solved: translation is always a set of decisions about how to render a text using a foreign set of tools. Readers in the United States are fortunate to receive so much contemporary Mexican literature in translation—far more than we receive from many other countries. The relato style of many of the essays in Planes Flying over a Monster recalls Fernanda Melchor’s This Is Not Miami, while the book’s decidedly Mexico City brand of cosmopolitanism and erudition echoes Valeria Luiselli’s essay collection Sidewalks.

Though Saldaña París’s novels have previously appeared in English, Planes Flying over a Monster feels like his coming-out before Anglophone audiences, announcing a major voice in the lettered world. In its off-kilter originality, the book invites its readers to perceive the absurd and literary in their own surroundings. For those who take Saldaña París up on the challenge, it promises to enrich both the lives and writing that follow. As he writes in “Assistants of the Sun”: “The world is a place magnetized by meaning.”

Caroline Tracey is a writer whose work focuses on the US Southwest, Mexico, and their borderlands. Her first book, Salt Lakes, is forthcoming from W.W. Norton.

More Reviews