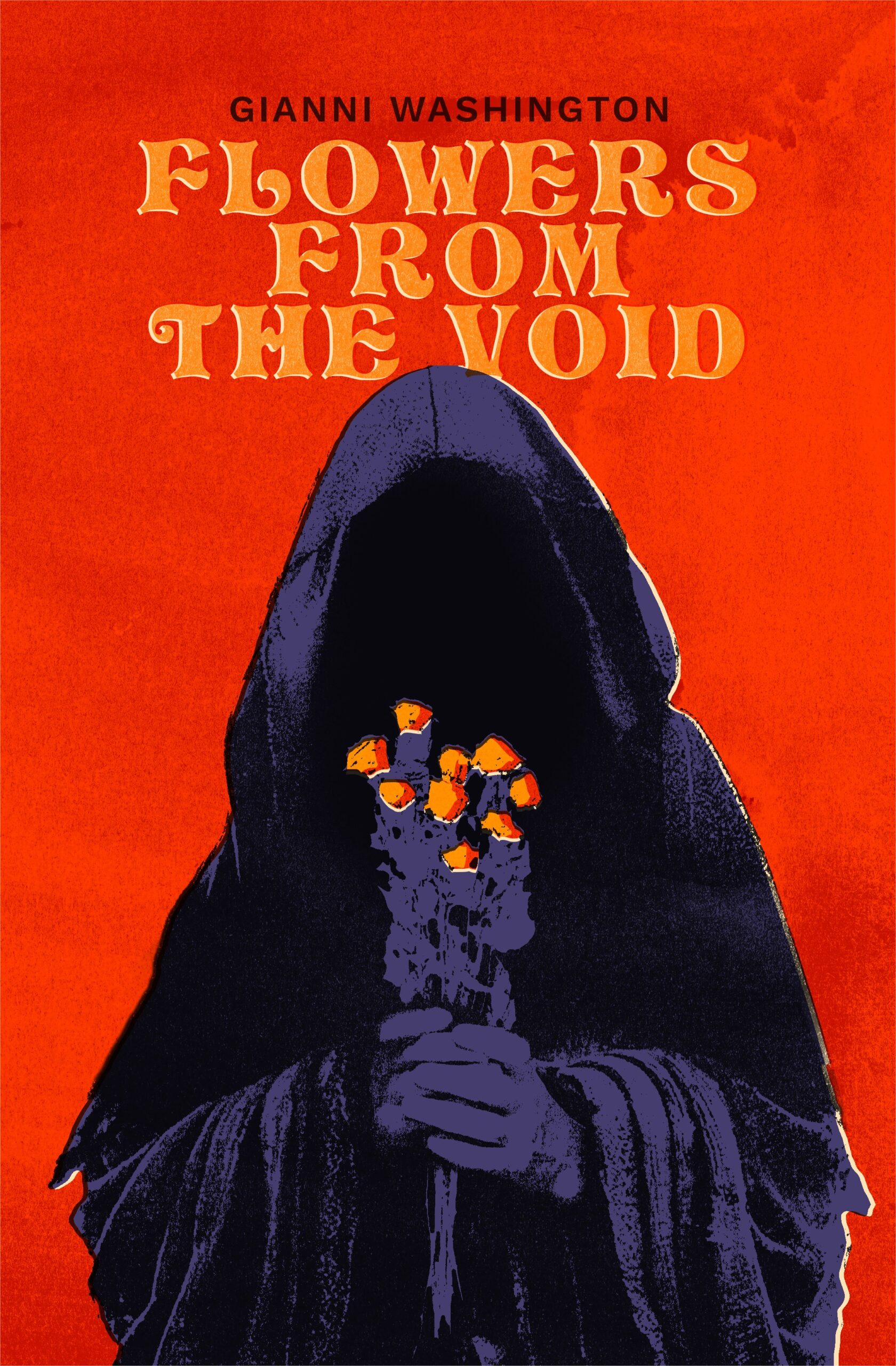

The Sweetest Flowers from the Void | Gianni Washington’s Flowers from the Void

Black experiences are not monolithic. This sentiment is often forgotten, as it sits in opposition to offerings from publishers, content creators, and movies that present stereotypical depictions of sameness, centered on the comfort or acceptability of such messages by dominant audiences. Thankfully, Clash Books has partnered with author Gianni Washington for Flowers from the Void, a short story collection that brings much-needed variety to the horror genre.

The unyielding empty space indicating a void is a useful metaphor for Blackness, as many members of the African diaspora feel isolated from the broader community through erasure and the invalidation of Black experiences. Victims of systemic racism understand how this void morphs into a type of bondage, frightening in its ability to also encompass a duality of monstrosity: Blackness labeled as monstrous and the truly monstrous treatment of Black people.

Yet within the darkness of the void, there also exist bursts of joy and color. Experiences of loving and being loved. Growth despite the barrenness of nothing. Flowers.

Washington chronicles the descent into darkness with the wrapper stories “Prelude: The Glass Terminal,” “Intermission,” and “Epilogue: And Now, Back to Your Regularly Scheduled . . . ,” about two young women enacting bell hooks’s theory of the oppositional gaze. In “Prelude”, one confesses, “When I’m alone, I do my best to avoid reflective surfaces because I know, with an itching certainty, that if I look long enough, I’ll see something I don’t want to.” Washington’s main point resonates as the two become ensconced in the void of a genre that does not often reflect their experiences, navigating their own increasing participation: the horrors of Blackness, while varied, also exist in tandem with the horrors of humanity.

One such horror is that of invisibility or liminality. “Under Your Skin” renders Phillip’s struggles to be seen and understood as a plight often experienced by people who are biracial or questioning their sexuality. A lonely teenager, he struggles to navigate an adolescence of invisibility. He is ignored by his peers and his teachers, while he is simultaneously hypervisible to his mother, who wishes to protect him from the world—to the point of suffocation. He is surprised, and titillated, when Martin, a smart and popular classmate, takes notice of him. Martin’s interest is apparent: “Martin brought his own face closer until their noses touched. His breath made Phillip’s chapped lips a desert. He didn’t know, couldn’t decide, if he minded.” His arousal, which runs parallel to shame and pain due to the violence Martin regularly inflicts upon him, gives him pause. Phillip does not initially understand that Martin finds kinship in Phillip’s isolation. Martin chooses Phillip as the target of his violent affections as a way to solve the issue of his own lack of companionship. Martin speaks for them both when he states, “Of course you do [want this], Phillip. Everyone does. To feel known—truly known—by another human being. People search their whole lives for that. A soulmate . . . and you’re mine.”

“Redemption Express” offers nuance to the invisibility of Black people. The narrator chooses to present as a Black woman, a persona they often use, knowing that visage will provide them with invisibility in the wider community. They muse, “Wearing this little number electrifies me, like I’m tiptoeing across a taut cord between buildings, five hundred stories up.” The image speaks to the power of being unseen. The only person who can, or will, see them is a little Black girl, drawn to the sight of another who looks like her. The task the narrator must complete is helped along by this choice, as anonymity and invisibility are beneficial to doling out supernatural justice. Conversely, visibility to the little girl gives the child confirmation that Black women are a part of society, working and living alongside everyone else.

“Go, It Is the Sending” explores the perception that Black women’s greatest value resides in their service to their loved ones and their community. The reader follows a nameless “She” who struggles with meeting the initiation requirements of the coven she wishes to join. Her overwhelming grief over her dead lover further inhibits her: “There was pain, yes, but it did not matter. She could feel no greater misery than had already eaten clean a space for itself within Her. The Mothers could not promise Agnes’s return.” In failing her final attempt at casting spells, She evolves from a nameless woman seeking validation into Mbweha, a powerful practitioner who does not require the fellowship of the coven to follow her path and discover her own strength.

The stories showing movement from erasure and invisibility toward agency and acceptance are where Washington’s lyrical storytelling is most illuminating. In “Hold Still” she introduces Mama Oak, who refuses to adhere to societal expectations that older women outside childbearing years have no value beyond caring for grandchildren. Mama Oak still has much to say and many desires; however, she cannot exist as she wishes, even at home helping her daughter and son-in-law in the wake of the latter’s accident. In a shared moment between Mama Oak and her son-in-law, he acknowledges her desire for something more, as he states, “Together, our individual longings emanating from us, Mama Oak and I watch the outlines of our offspring blaze with light borrowed from the setting sun.” He later finds Mama Oak has carved a space for an alternate existence where she is free to simply be and invite whomever she wants inside.

Ultimately, Washington ties the void of Blackness to the horrors of humanity in the poignant “When I Cry, It’s Somebody Else’s Blood.” The creature at the center of this story examines humankind through the eyes of various townspeople, developing an obsession with the orbs of flesh. Upon being introduced to human eyes, it explains, “The loveliness of this human’s orbs was unlike anything the creature had encountered in its celestial wanderings. It decided it must have one for its own.” Further examination teaches it that memories are created partially through sight. It then reaches this conclusion: “Humanity was so captivating. Every person whose memories the creature viewed had been wounded, and wounded others in return. But causing pain was a form of closeness; it was how they shared themselves with one another.” The creature eventually discovers that humans often hurt one another and that doing so allows a kinship of the human experience.

This kinship is the root of the flowers that bloom within the void of Washington’s collection. Vivid imagery, lyrical language, and complex characters are tools wielded expertly in this examination of Black experiences. A fitting summation from the epilogue:

The devouring eyes slurped up every scene, and at the end of each story we starred in, we were forced to dip our heads in acknowledgment of their adoration. It is their chosen purpose, to watch until they grow bored enough of cosmic births and deaths to switch the whole thing off. I wonder if I should feel grateful to have received their roses—ardently tossed at my feet as we took our final bow—despite my inability to choose whether or not to try and earn them. Maybe it’s being chosen that I’m meant to feel grateful for.

Blackness can be lonely, painful, and binding. It can also be a catalyst for growth and agency. The beauty of Flowers from the Void is that it presents no artifice about the darkness humanity can wreak on other humans. It also makes no assumptions that this darkness is all that can, or should, exist.

R. J. Joseph is the author of Hell Hath No Sorrow like a Woman Haunted.

More Reviews