Transmissions from Another World

music

By Stephen Thomas Erlewine

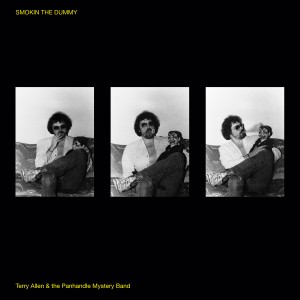

Terry Allen is such a singular artist that it’s easy to picture him forging his art in isolation, working without the assistance of collaborators. This notion can persist even in the face of the fact that, ever since releasing Smokin’ the Dummy back in 1980, Allen has shared billing with the Panhandle Mystery Band, a shifting collective who help bring his surreal country fantasias to life.

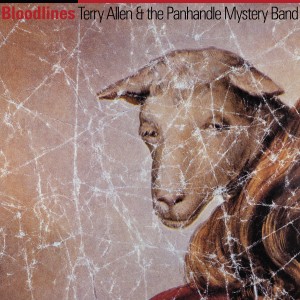

Smokin’ the Dummy and its 1983 successor Bloodlines were recently reissued by Paradise of Bachelors, the boutique record label who have been in the business of persevering Terry Allen’s recorded legacy. They’ve been at this task since 2016, when they reissued Juarez, Allen’s 1975 debut, along with Lubbock (on everything), the 1979 double album that cemented his reputation among a certain class of country music and art aficionados.

Creativity tends not to follow a straight line. Plenty of musicians create visual art; other artists dabble in music. It’s all part of a continuum. The striking thing about Terry Allen is how his visual art, his theater pieces, and his music all emanate from the same, peculiar source. All seem like transmissions from another world—a Southern-fried outpost existing in the middle of nowhere.

That outpost is Lubbock, a storied city residing in the Texas Panhandle. Allen grew up in Buddy Holly’s hometown, leaving at the age of seventeen to attend the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles after high school, moving with his then-girlfriend—now lifelong wife—Jo Harvey. The pair stuck it out in LA for quite a while, working as starving artists while Terry dabbled with music on the side. Occasionally, Allen wandered into the mainstream—there’s a thoroughly wild and weird clip of him performing “Red Bird” on Shindig in 1965, blowing kazoo to the thrill of a simulated crowd—but he gravitated toward the weirdos on the fringes of the Southern Californian scene, befriending the shaggy rockers in Little Feat, whose leader Lowell George spent some time in Frank Zappa’s Mothers of Invention.

As it happens, Terry Allen stumbled into his recording career. Juarez wasn’t designed as an album per se; it was an accompanying soundtrack to an art installation that encompassed lithographs and film. Not so much an afterthought as a piece of a bigger puzzle, Juarez was skeletal and almost misshapen, a record that required some concentration to parse. Nevertheless, the album gave Allen some juice—not enough for the big leagues, but enough for him to reside on the periphery of the outlaw country movement. Bobby Bare, a country maverick who couldn’t quite be called an outlaw, cut “Amarillo Highway,” while Little Feat recorded “New Delhi Freight Train” on their 1977 album Time Loves A Hero, raising Allen’s profile while also giving him some much-needed songwriting royalties.

All this activity inspired Allen to embark on an ambitious album where he cut full-blooded renditions of the songs he had written since Juarez. Initially, he intended to explicitly marry the two sides of his personality by having Lowell George produce one side of the record while his art-world friend Laurie Anderson helmed the other. Such a project was too precarious to come to fruition, so Allen headed back to his hometown to make Lubbock (on everything), working with the cream of the town’s music scene, including producer Lloyd Maines and Joe Ely’s backing band.

Released on Allen’s own tiny imprint Fate Records, Lubbock (on everything) could in no way be called a hit. But its off-kilter sprawl resonated among certain audiences. Nominally country and thoroughly Texan, Allen walked the fine line separating Americana myths and satire; he was invested in the sounds and sights of the Southwest, which is why he didn’t take all of its pageantries particularly seriously. Robert Christgau, the chief critic at the Village Voice, summarized the album by saying, “This time he sings like Kinky Friedman with a sense of humor,” nailing the ribald spirit that underpinned the tunes. But Wilco’s frontman Jeff Tweedy captured Allen’s appeal better: “Those records have a real life. They find the people that need ‘em.”

Lubbock (on everything) found enough people to give Allen momentum—an illusionary force that still pushed him forward, even if it was without much direction. Yet Allen didn’t jump to a bigger label. He stayed on his independent Fate and delivered Smokin’ The Dummy, his version of a down and dirty outlaw record. This wasn’t a solo album; this was the work of the Panhandle Band, which amounted to Lloyd Maines playing guitar, his brothers Kenny and Donnie on bass and drums respectively, with guitarist Jesse Taylor and utility player Richard Bowden rounding out the lineup. It was a group that knew each other’s strengths and weaknesses, and a group that could be trusted to wade through the ephemera of Allen’s back pages, which is what the record effectively was.

Smokin’ the Dummy is a classic sequel. It’s a patchwork of older songs, tied together by newer material that gives it character and shape. Allen excavated “Red Bird,” the song he played on Shindig during another lifetime, then fleshes out the jape “Cocaine Cowboy,” which he auditioned for NYC art collector Earl McGrath at some point in the past (that version can be heard on Earl’s Closet: The Lost Archive of Earl McGrath, 1970-1980, a new compilation from Light in the Attic). The album’s touchstone piece is “The Heart of California,” a swampy rocker written in tribute to Lowell George, who died in 1979. It’s an unusually sentimental gesture but it also speaks to how Smokin’ The Dummy feels like the work of a Southern-fried rock & roll band—of redneck hippies attempting to toe the line. Allen cracks doper jokes on “Cocaine Cowboy” and reworks Chuck Berry on “Whatever Happened to Jesus (and Maybelline),” but this album doesn’t linger on the byways so much as it attempts to adhere to the straight and narrow. “Cajun Roll” may be decorated with fiddles but what resonates is its heavy-footed thump, a juke-joint groove that can also be heard on “Texas Tears” and “Roll Truck Roll.” The latter has nothing to do with the Red Simpson song of the same name—Simpson was the king of the truck-driving country coming out of Bakersfield—but would easily sound at home in the cab of an 18-wheeler. The spare, quiet moments and poetic sketches are muscled aside by this raucous rock & roll, a trade Allen never would make again.

Such an emphasis on backbeat and cacophony means that if any Terry Allen album could be called conventional, it’s Smokin’ the Dummy. So maybe it’s not a surprise that it found fans in more conventional quarters. It raised enough of a ruckus to earn a positive nod from Easyriders, a motorcycle magazine distinguished by its half-nude female cover models. But Allen never was quite so vulgar as the bikers that constituted Easyriders’ readership. Although he may have been blasphemous, he wasn’t callous. He was comfortable in the assumption that his audience would follow his allusions and detours, connecting seemingly disparate dots. While he buried that aesthetic on Smokin’ the Dummy, he pushes it to the forefront on Bloodlines, an album where his melancholy streak tussled with his earthier tendencies.

Bloodlines took a long time to complete. The first sessions were held in August 1982, the last in 1983, and the album itself only trickled into the marketplace later that year. It eventually cultivated an audience large enough to attract the attention of David Byrne, who later hired Allen as a collaborator on his outsider art paean True Stories (released in 1986). Byrne and Allen remained friends and occasional collaborators for decades. In fact, this past May, Byrne joined the Panhandle Mystery Band at Wilco’s Solid Sound festival to play on a cover of his “Buck Naked.” While the association was fruitful, it also closed the door on the period when Allen could be considered some kind of country artist. He may have been well-versed in every Western style from woozy Tex-Mex mariachi bands to backwoods gospel—styles that surface as “Cantina Carlotta” and “Oh Hally Lou” on Bloodlines—but he fashioned his familiarity into art that challenges, not comforts. Allen’s aesthetic instincts are a key reason why he remains a quintessential cult artist: the kind of musician whose audience stumbles upon his music, not one who eases strangers into their circle.

Perhaps Bloodlines is proof that, as the LA Herald Examiner observed in 1984, Allen was “making the most unique art-pop of our time,” a notion underscored by his friend Dave Hickey. After hearing the record, the art critic told the singer/songwriter, “I’ve never heard such a consistent assortment of unpopular styles.” Hickey’s assessment of Bloodlines may be on the money, but the record is also one where Allen articulates his idiosyncrasies with remarkable depth and soul. Where Lubbock (on everything) benefitted from its shoestring eccentricities and hazy sprawl—qualities that make the double album feel suspended in time—Bloodlines is concentrated. Consequently, the melancholy underpinning the secular gospel of “Bloodlines” becomes overwhelming in its emotion, even as its sentiment is immediately undercut by the riotous “Gimme a Ride to Heaven Boy,” wherein the son of God carjacks a drunk driver, claiming “the Lord moves in mysterious ways and tonight I’m gonna use your car.”

“Gimme a Ride to Heaven Boy” is deeply funky and weird, the kind of song that seems to crystallize the spirit of 1976, when the outlaws Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings were itching to carve out their own path, one that lead far away from Nashville. Meanwhile, Terry Allen was so unconcerned with being part of the zeitgeist that he wound up delivering his outlaw records years and years after the attitude was marketable, a stance that underscores his utter indifference to the winds of popular culture. He’ll absorb it, sometimes sample from its wares, learning enough to send it up but never really participating in it. This outsider stance personifies the deep, inherent weirdness of Texas better than such straight arrows as George Strait. Allen had no inclination or patience for honky-tonk revivals. Rather, he built off the shared language of the Lone Star State, burrowing into its funk, sadness, and defiance, accentuating the weirdness so heavily he wound up making records that are perhaps better appreciated decades after their release than they were at the time. All the product affectations of the period—usually apparent in the percolating roadhouse rhythms and thick shards of guitar—suggest an era, not a specific place in time, capturing the weird, wooly days of the late twentieth century, when egregiously talented oddballs like Terry Allen had the opportunity to chase his muse with the assistance of a white-hot band in a good local studio. They don’t make records like these in the 2020s—but, then again, nobody but Terry Allen made records like this back in the day, either.

Stephen Thomas Erlewine is a Senior Editor at Xperi, whose database of music information is licensed throughout the internet and can be easily accessed at Allmusic.com. Over the past three decades, Erlewine has written thousands of record reviews and biographies. He’s also contributed to Rolling Stone, Spin, Pitchfork, Billboard, and the Los Angeles Times and has written liner notes for Vinyl Me Please, Craft Records, and Sony Legacy.

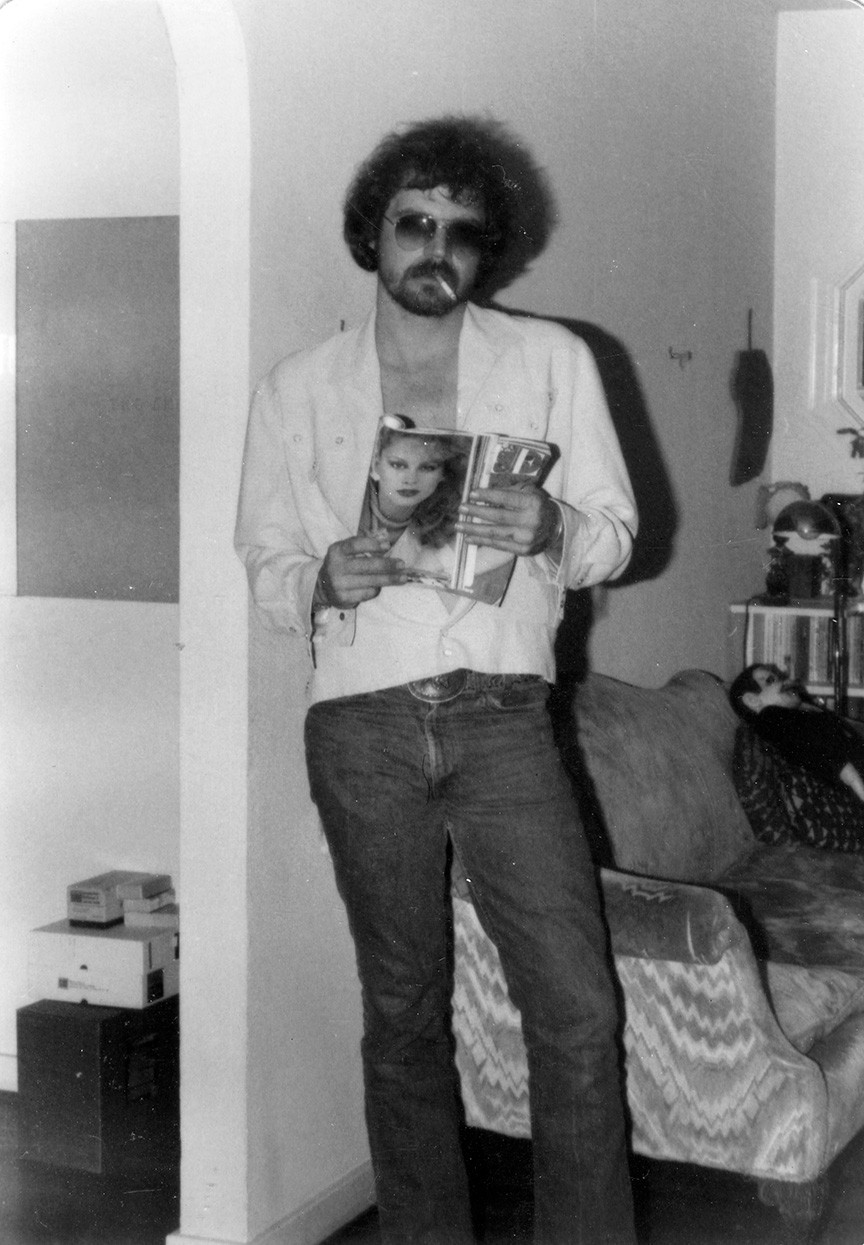

Photo: Jo Harvey Allen

More music