Trust in the Whispers of the Universe and Persevere

Reviews

By Mila Jaroniec

For an artist, success doesn’t come without anxiety. There is the pure joy of creation in the dark, before anyone knows who you are, before you have a responsibility to the world. And there’s always a responsibility—if only to the version of yourself that people have seen.

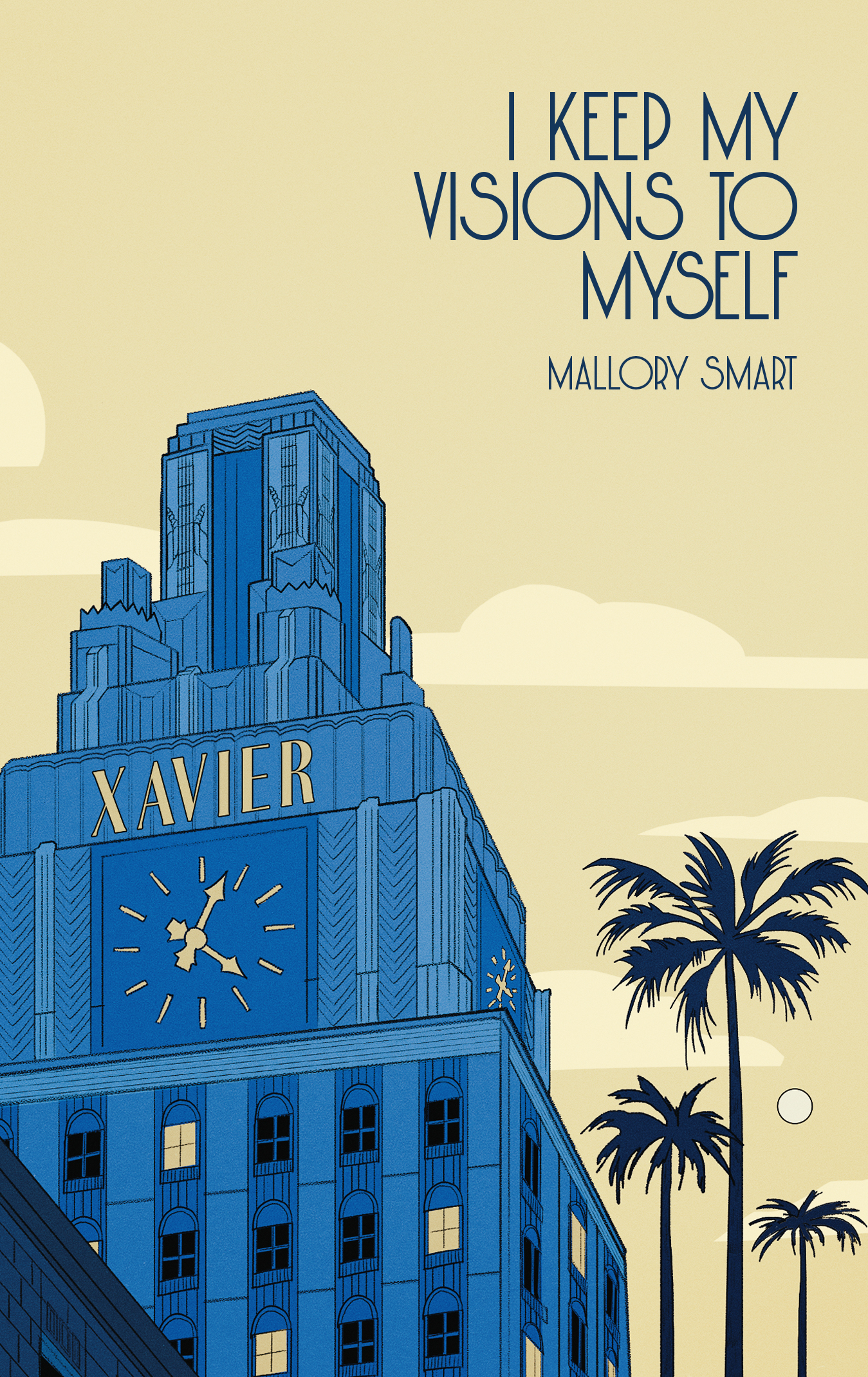

Mallory Smart’s I Keep My Visions to Myself (With an X, 2023), is a portrait of the artist at an impasse, a journey through the landscape of existential anxiety with an iPhone in your pocket, a drunken love letter to Lost Angeles, a cosmic imperative to find your roots and grab hold. It is universal truth in the form of a young artist’s story: “You need to start thinking of your life as something you chose and not something that was forced on you.”

Twenty-six-year-old Stevie, unsubtly named after Stevie Nicks by her alcoholic mother in an attempt to transplant her own unrealized dreams, is a musician on the brink of fame who finds herself at a stalemate when the opportunity to record a new album and go on tour with her band arises. On the one hand, it’s what anyone would want. On the other, there’s the consequence of fame—the risk of belonging, in some sense, to the audience and losing the vital, untethered part of yourself. Stevie grapples with this over the course of a few days in LA as she wanders around, hanging with friends, thinking, drinking, and leaving her band, who are waiting for an answer re: to tour or not to tour, on read.

The anxiety runs wild.

Stevie is almost famous. She’s famous enough to get recognized when she goes out, but not famous enough to get pulled apart on Twitter or have her pores zoomed in on on Instagram. She isn’t being perceived that way yet, but she knows she will be if she takes the next step. In a way, however, that step has already been taken: “[The music] was no longer poetic or pure. Every word and idea was coming from a place of anxiety.” She is already writing songs with the audience in mind.

In On Writing and Failure, Stephen Marche posits that “success destroys what gives success.” He also quotes John Updike, who writes that celebrity “is an unhelpful exercise in self-consciousness…One can either see or be seen. Most of the best fiction is written out of early impressions, taken in before the writer became conscious of himself as a writer.” It’s the difference between Writer and Author. A writer writes. An author has written something on which they’re now an authority. The success, usually hard-won and deeply wanted, comes at a price. A brand to manage. A persona to inhabit. An incohesive, complex self to put away.

The audience informs everything artists do. We’re conscious of its presence, even when we’re trying not to be. It’s a consciousness baked into us from being overexposed—we filter, we curate, we self-edit, self-promote, self-censor. Articles, newsletters, podcasts all tell us: it’s not enough to write a book, produce a record. We have to post about it, show the process, show our cards, connect, engage, relate, bleed out more and more of ourselves to stay “relevant” at all costs, at the expense of what truly requires our energy. Even when we attempt to intentionally transgress, by posting semi-nude photos or problematic takes or by airing our dirty laundry, we do so self-consciously, with one hand on the pulse, one eye on our audience. And even if they don’t expect anything, even if it’s all in our heads—people, of course, don’t care as much as we think they do—we expect them to expect something, we expect them to care, and that’s enough to knock us off course.

Not only does this headspace get warped, it gets unbearably lonely.

At the center of Stevie’s narrative is the concept of “tribe”: the idea that some people are “fundamentally connected in a way that [goes] beyond consciousness,” who are “destined to come back and find each other,” made of the original universal atoms that over time keep “coming back together creating a bond that [is] beyond reason.” Impossible to prove; intrinsically makes sense. It’s hard to picture a world in which Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham do not find each other.

Stevie tries to find her people, find her place. She wanders around LA, to be alone, to take a breath, to find “the people who she could be with and not be on brand or be nice to.” Eventually, she ends up in the Cecil Lounge at the Hotel Xavier, a decadent ruin from a bygone era. She overhears the phone conversation of someone she takes to be an agent, who for some reason delivers the “Choose life” monologue from Trainspotting to whoever’s on the other end. She gets martini-drunk with Lily, a mysterious lounge pianist who recognizes her despite her best efforts. They talk about romance and the possible suicide in progress upstairs, the Hotel Xavier being exactly the type of place one would go to disappear. Stevie gets inordinately drunk and wakes up the next morning in one of the rooms, alone, unsure of how she got there, with a hazy recollection of the night’s events. She discovers that she has sent a bevy of drunk texts, including one to Alfie, her ex-boyfriend, making plans to get sushi and see a movie that night. He wants to see her, which is a good sign—she misses him. Things made more sense when he was around. She has to pull it together. Without paying or checking out of the hotel in any way, she leaves, calling her ride or die, Finn, to come rescue her.

Stevie has a choice: Go on tour with the band, release a studio album and promote it, step into the role of Musician, be public, make her mother happy, live up to her namesake. Or lay low and play music for fun, for the soul, without career ambition, any audience-facing nonsense. A problem, when all we want is for our art to connect, but all the world wants is something it can describe and digest, something it can adequately summarize in a fifteen-second TikTok. But it’s not the audience that trips us up, ultimately. It’s our self-conscious, self-effacing perception of it. The album she’s been writing, Stevie realizes, wasn’t working because it “was forced and full of ideas she thought people would like to hear.”

In the image-driven media machine, the very real threat of losing one’s true north can be mitigated by staying true to oneself, whatever that means. Sometimes we don’t know what that means, Visions suggests, because we can’t see ourselves. That’s where our true friends come in: to see us, to hold us, to guide us back to center. The ones whose atoms have connected across lifetimes. The ones who will remind us that when we create from a place of unfiltered truth, there’s no need to reach for our audience. Our audience, those who truly understand and connect, will always reach us.

Mila Jaroniec is the author of two novels, including Plastic Vodka Bottle Sleepover (Split Lip Press). Her work has appeared in Playgirl, Playboy, Joyland, Ninth Letter, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, PANK, Hobart, The Millions, NYLON and Teen Vogue, among others. She earned her MFA from The New School and teaches writing at Catapult.

More Reviews