Two Places at Once | Talking Shop with Thomas Dollbaum

Interviews, music

By Ashleigh Bryant Phillips

For the sake of time, we’ll start this story in New Orleans. But this story’s not about New Orleans. It’s about how you can be two places at once. You’ll see. If you wanna know how it all began, read the next paragraph; otherwise, skip to paragraph three.

(It all began when a woman from a big family in Indiana met a man from a big family in New Jersey. They started a life in Tampa, named their first son Thomas. The man from New Jersey sold windows and the woman from Indiana encouraged Thomas to sing.)

Thomas is in New Orleans, screening in his porch. He’s waiting for a phone call. He prefers talking on the phone because it’s off-the-cuff. Don’t have to analyze or overthink. It’s quicker and he’s got work to do.

A screened porch. You can enjoy the breeze without the mosquitos. Thomas already got the screen from Lowe’s—he’s just got to fit it.

But the phone call.

A writer’s gonna call him for an interview. (She’s not me, she’s from Bryn Mawr. I’m from a town in North Carolina you’ve never heard of. You’ll see.)

Thomas has just released his debut album, Wellswood. Named after a neighborhood in Tampa, where he lived before he left town. Eight songs, written after he’d moved to New Orleans, homesick, nostalgic. Recorded in some old Delta hotel room. Mastered by someone in Memphis who worked with John Prine.

If you haven’t listened to Wellswood, you should listen to “Florida” and “Moon” right now before you read any further.

Back to the story.

Thomas is home from touring. He broke even. Sold merch with his dog’s face on it. (His dog is named Doody.) Hung out with locals after the shows. Went out for some beers, got invited to some BBQs, talked to everyone like he’d never known a stranger.

I saw him on his Asheville stop. Seemed like every local writer and musician I admired was there. All my friends were there too. Thomas played a Larrivee guitar. He was wearing worn-out loafers and ate a whole hamburger before telling us the inside was raw. He told good jokes. And he told us the van had hit three birds on the tour—he laughed it off but you could tell he was bothered by it too. He was raised Catholic.

There was an old woman who worked at a gas station. She said Thomas sounds like good old country music. Some dude said he sent a video of Thomas to his church choir director’s mama and she said Thomas has great harmony. “He can throw his voice high and sling it low,” someone said. “He can really sing.” Someone else said, “He’s taller than I imagined.” Multiple indie rock fans on multiple occasions said at first listen that Thomas sounds like Mark Kozelek, but Thomas has never really listened to him. He writes better songs than Mark Kozelek anyways.

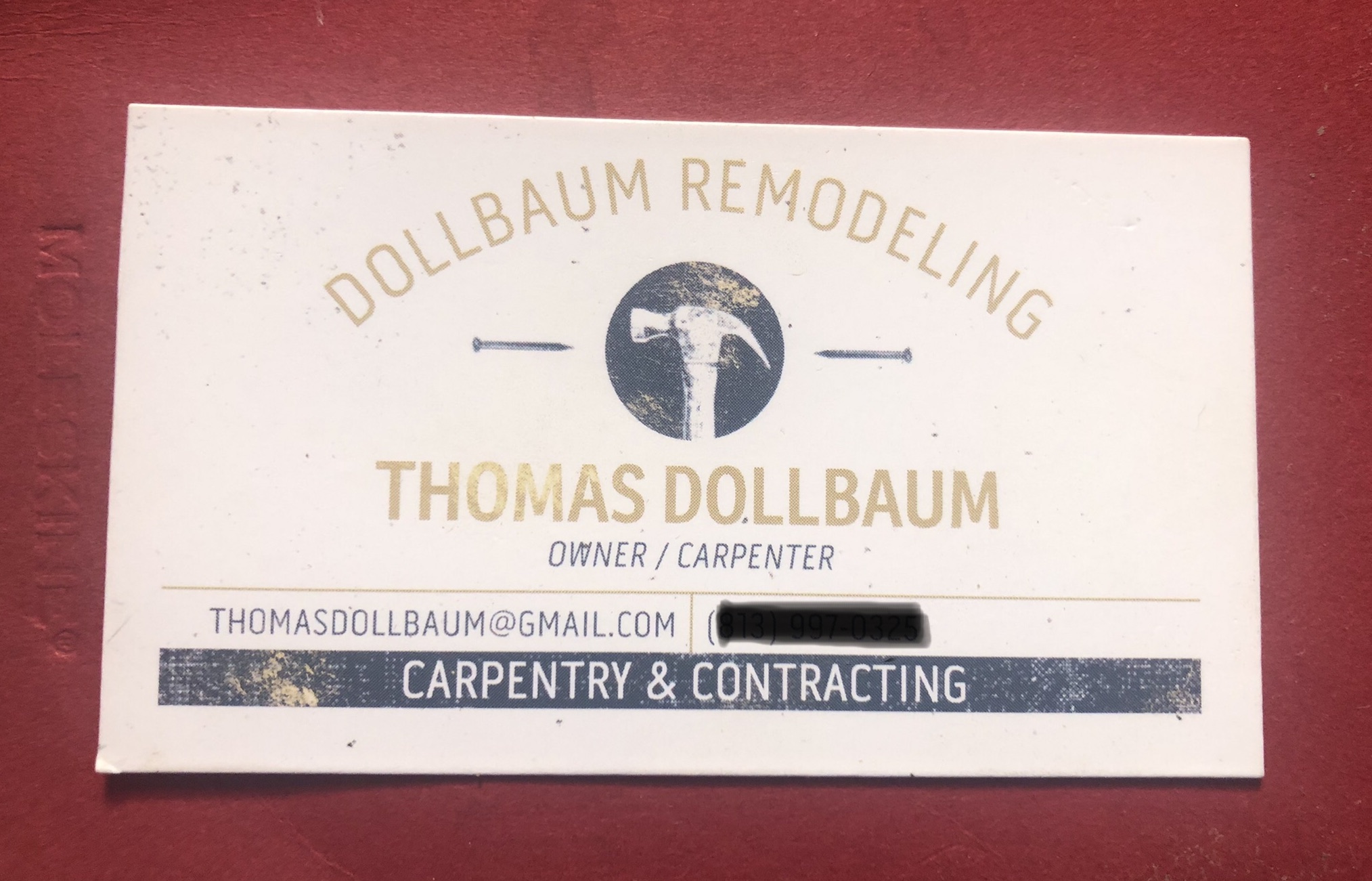

So far, in the press, all the writers have been romanticizing Thomas’s day job. He’s basically a handyman, putting in electrical, plumbing, baseboards, throwing up fences. The writers eat up that he’s got an MFA in poetry too. Even better, his lyrics talk about falling in love and huffing paint—some Florida shit. Calling him the working-class poet. The carpenter mystic. Grit-lit. Americana. Alligators. Methadone. Raymond Carver. The Allman Brothers Band.

Thomas just enjoys working with his hands, telling stories, and making them into songs. He’s thankful he’s got an album, thankful if you listen. He’s authentic and expects the same from you.

The writer calls. She’s been assigned to write an article.

“I don’t know anything about Florida,” she says. “One time while visiting my grandparents there, we went to buy catfish from these rednecks who had all these fish squirming in the bottom of a boat. The smell. Do you fish? You look like a fisherman on the cover of your album. Like American Mythology–like.”

“Sure, yeah I fish.” Thomas laughs. He goes inside his house. It’s too hot out.

“And from your lyrics, I just have to ask, are you an alcoholic?”

“No,” he says.

“You’ve never been anywhere to dry out—as they say?”

“No.” Thomas grabs a glass, fills it with ice and water. Sits at the kitchen table.

“There’s just so much addiction in your songs.” The writer pauses. “I did a little bit of research before I called. Did you know the overdose rate in Florida is 50 percent higher than the national average? And in Tampa Bay it’s 9 percent higher than the rest of the state? Nearly three people die every day in the Tampa Bay area from an opioid overdose.”

“I didn’t know that,” Thomas says, “but it doesn’t surprise me.”

“There’s also this stuff in your lyrics about arriving back and leaving again. Did you know the port of Tampa is the largest port in all of Florida?”

“Florida’s a transient place,” Thomas says. He leans back in the kitchen chair.

Thomas doesn’t know anyone who’s been in his hometown for generations and generations. Most everyone has moved there. It’s really flat, unassuming, pretty. The beach and the city. Thomas has always thought, Maybe like California, but just more poor. But he doesn’t say this.

“Breeding ground for people trafficking and hookers and addicts,” the writer lady says. “Did you know that Tampa has more strip clubs than any other city in America? It has more strip clubs than hospitals, high schools, and fire stations.”

“Seriously?” Thomas laughs. “Sounds like you really found some hard facts.” He shakes the ice in his glass, makes it ting.

He doesn’t tell her about the house on Rome Avenue, back in Wellswood. Grimy floors, linoleum, wood paneling. Right across the river from the Dutch Motel, where they say sex workers live. He doesn’t tell her about the hooker he met on the Greyhound from Atlanta. She sat beside him and told him everything. Like no one in the world had ever listened to her before. What color were her fingernails?

“I just want to know if you’ve ever known anyone to have these kinds of problems,” the writer says.

“Not personally,” Thomas says.

“You just write about these characters, these people, these situations, so intimately,” the writer says. “But let’s shift gears . . . when did you start playing music?”

“In high school I fronted a reggae band,” Thomas says.

“What? Really? This is amazing!”

“Yeah, I mean—when I was in high school, we smoked weed and sat around listening to Alton Ellis and old dancehall. But we listened to Sublime and Wu-tang too.”

“Did you play covers?”

“No. I wrote original songs. Just dumb and nothing special.”

“Did you grow dreads?”

“No.” Thomas sits up in the kitchen chair. “But we played all over town . . . We were just fucking around . . . Seems like our bassist was always on roxies.” He figures the writer won’t know what roxies are. He’s thankful she doesn’t ask.

But for those of you who don’t know what roxies (or blues) are: Roxicodone is one of the brand names for oxycodone, the highly addictive painkiller.

Back to the phone call.

“Well, how did you transition from reggae to what you’re doing now?” the writer asks.

“I discovered songs that told stories like John Prine, Molina, Townes. I’ve always liked hearing good stories. And then I went to college and found out about poetry.”

“Were you the first one in your family to go to college?”

“Yes.” Thomas says. “But anyways, my professors showed me poets like James Tate, and I just didn’t know poetry could be like that.”

“Like what?”

“Absurd and profound and playful and devastating all at the same time.”

“I bet you majored in English.”

“Oh yeah,” Thomas laughs.

“And I bet your professors encouraged you to get an MFA.”

“That’s exactly right. But I mean, if I had stayed in Tampa, I’d be selling windows with my dad. And I’d just always lived there. I was ready to see something else.”

What did that hooker woman on the Greyhound say? Grew up in my hometown and it was shit, got me a new town and it’s shit too. There’s gotta be something better than this. Her knees were knobby. They were trembling. Not out of fear though, but pent-up power, energy. Ready to explode.

“What were you writing about in the poems that got you into your MFA program?” the writer asks.

“Nothing worth mentioning,” Thomas says. “They didn’t give me any funding, so I guess I was fool enough to take out loans.”

He shakes the ice in his drink again.

And the writer just won’t quit.

“You just sound so convincing,” the writer says, “singing your songs like you’ve lived them. But you’re telling me you didn’t. It’s like you’re doing something similar to Johnny Cash, or let’s say Breece D’J Pancake or Larry Brown.”

“Those last two names you said, are they writers?”

“Oh yeah,” she says. “Surprising you’ve never heard of them.”

Maybe he had. When Thomas got to New Orleans for his MFA, he got nervous sometimes. How his peers talked about what they were reading. All theory and examination. He wanted to be throwing up fences instead. A fence is a fence, a baseboard is a baseboard. Always. And he missed Tampa. There everything is what it is—even with all its fucked-up-ness. Even when folks called from home to say so-and-so had overdosed.

He wanted to go back to the beginning.

One of Thomas’s professors had said: “In the Beginning was not the Word. In the Word was the Beginning.”

Now let’s stop right here and go listen to the first words on Wellswood. Track one is “Florida,” and it goes:

Well, look out Florida you’ve got a hooker

in your back, she’s riding high with some trick

on Sligh Street, she’s in the corner store of the

Sonoco trying to buy cigarettes, she says it’s her

birthday, God help her.

You’re Florida. I’m Florida too. Laying up in the Dutch Motel all day. Riding in the Crown Vic. Huffing paint on Hillsborough Avenue. Bragging, limping. Staying up all night to watch the sun burst through the room. Sorry. Still here, still hard to love. Come back to me come back to me come back to me it’s alright. I don’t care. Aileen, loneliness can’t reach us. I’m the hooker, the dog, you are too. Well, look out Florida. Look out. Nothing good comes from Florida—including you.

“Look,” Thomas says to the writer. “The songs I write have a lot of me in them, with the stories I hear, like putting myself in someone else’s shoes. And it gets hard to tell which is real and which is made up.”

“I see,” the writer says.

Thomas throws back the last bit of water that’s in his glass.

“What about New Orleans?” the writer says. “We haven’t talked about that. It was surprising to see no bayou or gumbo in your songs. Or the Mississippi river.”

Of course, this writer doesn’t get it. What place is. Place is memory. Memory is experience.

Thomas asks the woman where she’s calling from.

“I live in Fishtown, in Philadelphia,” she says.

“But where are you from?”

“I’m from Montgomery County, outside of Philadelphia.”

“Never heard of it.”

“Well actually I’m from Bryn Mawr,” she says.

Thomas gets up from the kitchen table, puts his glass in the sink.

“I love New Orleans though,” she continues. “It’s unlike anywhere else in the world.”

“New Orleans is amazing,” Thomas says, “but Florida will always be my home.”

Thomas looks out his storm door to the porch. Doody is laying out there, sunning.

“I’ve got one more question for you,” the writer says. “So if lots of people from Tampa are having it hard now, with all sorts of addictions, don’t you feel guilty a little? You were able to leave. What about the people who got stuck there?”

Place is memory. Memory is experience. But memory is also imagination.

As a kid, Thomas counted rosary. Like I said earlier, on tour, the van killed three birds. In Tampa there were night herons. Sonocos. Gold teeth. The brothers in Robles Park dance all day. C’mon, honey.

“Tampa’s not all that bad,” Thomas says. “I’d live there again if I could. It’s just getting expensive. Maybe one day I’ll move back, but not right now.”

“But don’t you ever wish you’d been born somewhere else?”

“There’s nowhere else I could have been from.” Thomas says, “Now if you excuse me, I’ve got to get back to screening in my porch.”

Thomas hasn’t finished the porch yet. But he will soon enough. It’ll be a good place for writing and maybe singing. Going back and into the future all at once.

Ashleigh Bryant Phillips is from Woodland, North Carolina. Her collection, Sleepovers, won the C. Michael Curtis Short Story Prize. Her work appears in The Paris Review, The Oxford American, and others.

More Interviews, music