Unsafe, Unthinkable You

Reviews

By Joe Koch

The title is a threat.

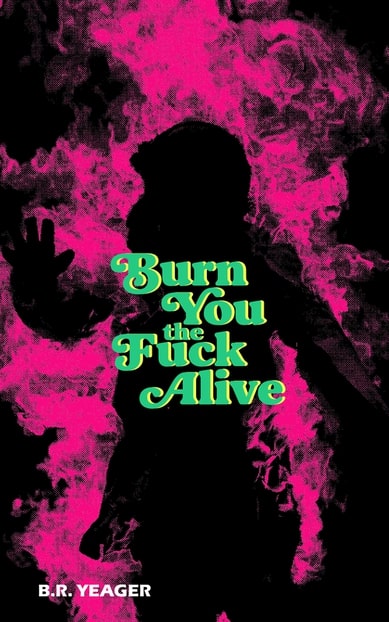

I’m three stories in before I realize I’m the target. That’s when author B. R. Yeager, who is also credited as Art Director, reveals his book’s title page and table of contents. I’ve just read about arsonists, and as I turn the page, the words Burn You the Fuck Alive blast me in the eyes.

The juxtaposition shocks. After being lulled into the dreamy violence of the story “Where We Breathe,” mirror images of the cover art and this inscription emphasize that we readers are not exempt or safe. The You of the title is us.

But this book isn’t content to make threats. It means to interrogate who You are beyond being a reader. Who are You right now in the twenty-first century, in this age of pandemic deaths and right versus left? Who are You privately, in relation to power, especially when you feel powerless? These are questions this book—although it’s not so much a book as it is an aesthetic object, and perhaps it’s less an object than an act of aesthetic terrorism—asks. It imposes a relationship with the speaker embedded in the text through frequent use of second person, the most accusing literary voice.

The title story manifests like an interruption after the table of contents, which I had to check in order to identify it. Briefly insidious lines and phrases take up several full pages. “You’ve dreamed about me. A face you thought was your own invention. But it was really me. I was there, and I saw you too.” Before we reach anything as reassuring as a story, more illustrations appear: grainy, newspaper-like images in black and white that obscure as much as they elucidate, like an old mirror too foxed to be trusted.

Then come words and images like graffiti, crime scene photos, or the entries in a school shooter’s diary: “I ended the world just to get to you.” Hints at stunted longing and some other voice that is not quite you, me, or the author, but the thing behind the mirror we don’t see or own: the hidden You.

Turn another page. One image is rendered twice on both the front and back, inviting You behind the mirror. These two-sided mirrors introduce most of the stories, and I’m thinking as I read how a reflection creates an inverted image. Horror fiction also does this: it reflects an opposite or shadow-self we strive to keep hidden from ourselves as much as others. Ideas of splitting, or perhaps unity within duality, seem contained in these mirrored illustrations. Through the action of turning the page, You may glimpse the other side of the mirror, but only as it disappears.

The first three stories work as a pandemic grouping, suffused with isolation, paranoia (“I can sometimes hear the neighbors thinking”), and lives mediated through internet connections, if they are connected at all. I don’t know if they were written during lockdown, but they seem to take place there. (You remember lockdown, don’t you? That major historical, life-changing event that we’re trying to forget.) The people in them turn away from life and each other until they reawaken through violence. I wonder if that’s happening right now in America—if our unspoken pandemic grief is fueling an awakening that expresses itself as fascism.

For instance, in “The Young People,” a couple becomes isolated, disassociated, and emotionally immobile while working from home. Yet their lack of desire explodes into sadism. Their necrotized sex life rekindles through shared violence. The male partner’s adamant justification (using unreliable online resources) of his rightness, and the female partner’s uncertainty and inability to openly question him or dissent, feels intimately plausible despite the extreme horror.

The horror is magnified by how very normal the characters seem. Yeager expertly grounds his weird fiction in the familiar while simultaneously revealing a horrid emptiness and violence lurking in interstitial spaces. The inertia of repetition roots many of his characters in the mundane: working, not working, smoking, scrolling, masturbating, getting high, not being able to get it up, killing time, enacting gestures that look like life, functioning or barely functioning within the parameters of societal relatedness and expectation. Everyday life is full of small disassociations, like thinking about dinner instead of paying attention to where you’re driving. In Yeager’s fiction, these empty gestures enlarge, perpetuate, and perpetually empty out meaning. Holes develop, perforating reality. An alternate, heightened reality breaks through, opening the characters to violence. The ordinary calls forth the unthinkable.

Unseen worlds surround and permeate quotidian reality, but not the reality of hustle culture, nuclear families, and bootstrap psychology. Yeager’s fiction is embedded in the subculture. If you’re a weirdo or artist like me, Burn You the Fuck Alive is as charming and funny as it is horrific. Humor lends veracity. We know these characters. We are them, at least outside of our day jobs. Yeager really shines at using minimal description to invoke an immediate, immersive state of identification. He disappears as an author and lets his characters speak and act out. Their instantly recognizable humanity and depth disarms us and complicates the title’s threat.

Because if it’s You on both sides of the mirror, how will You ever be safe?

Turn another page. A story that is not a story: a zine made up of xerox-quality images, perverse game cards, and ripped up snatches of text. “In the Shadow of Penis House” is both a deliberately stupid title and a nod to H.P. Lovecraft. Our cosmic horror daddy often used epistolary devices to place the reader a few steps outside of the narrative, a tactic that can fail miserably. But when it works, it makes the reader all the more eager to get in. Maybe I’ve just made some sort of complicated phallic joke, but rather than analyzing or correcting that, what really interests me about “In the Shadow of Penis House” is how it looks like a ratty DIY version of an RPG-style card game. It looks out of place in a book, yet it so effectively lures the reader inside the narrative’s crumbling recesses, surpassing a traditional story.

Using second person, “Penis House” places You at the center of some rotting mansion as both victim and heir, or perhaps neither. Nothing is certain in Yeager’s fiction. Perhaps you’re just a farm animal facing slaughter, or perhaps even less than that, no more than “a goddamn pile of hooves!”

Formally experimental, this piece treats the reader as ghost, You reduced to an uncertainty, haunting the fragments of an incomprehensible but—if the title is to be trusted—fundamentally patriarchal structure. Self-creating You takes us in and out of mirrors, in and out of (penis) shadows, and immerses us further in a task made of broken architecture or an anti-coming of age game. But this game offers no key to its symbols, no rules of play. How are we supposed to navigate if not by participating in the game’s abuses and acceding to its hierarchy?

In this and in another (possible) (nothing is certain in Yeager’s worlds) game story, “Arcade,” the protagonist seems to be trained to assault or be assaulted through an inconsistent system of punishment and reward that exacerbates his aggression. It’s recreational, all for fun, and again told in second person. You murder and assault indiscriminately. You awaken from the game world certain, in a twist on Zhuangzi’s butterfly paradox, that your recent rampage of slaughter and mayhem is “the truest thing you’ve ever known.” Your body feels it, and there’s a satisfaction and sense of rightness in the wording.

You seems to be primarily masculine, although “Poison Nurse” and “Puppy Milk” feature female protagonists. The use of second person in “Poison Nurse,” however, pushes me out of the narrative. It lacks the demanding force of You elsewhere in the book. Interspersed with first-person sections, it reads (in my opinion, which is purely subjective) like a cheap solution to the problem of switching between past and present; it’s more distraction then enrichment. A minor complaint. A bigger one is the glaring lack of queerness. Glaring because, in his previous novel Negative Space, Yeager wrote queer and transgender characters with deftness and confidence. I know he can do it. I want him to do it. And, nearing the end of Burn You the Fuck Alive, I am longing, I am begging, I am screaming for some relief from the oppressive, nonstop heterosexuality.

What I get is more oppression. Fair enough, since good horror has unflinching realism at its heart. The single piece that mentions queerness literally stomps the suspected homosexual into pulp. The title contains a military reference, retrospectively conjuring uniformed gangs and jackboots by the story’s end. Much like a ritual sacrifice, even the victim seems to posthumously approve and accept the inevitability of a group apotheosis of violence.

As in “He Just Takes It,” “The Buried Man,” and (maybe) (nothing in Yeager is certain) several other more ambiguous stories in Burn You the Fuck Alive, death will not end the suffering or the narrative. When you die, when you burn, these fascists really are going to Burn You the Fuck Alive.

And it might be worse. You might be one of them.

Can a book be an action instead of a text? Can the goddamn thing come alive in my hands? Will it catch fire when I turn the next page? This object or action called Burn You the Fuck Alive pushes at the confines of being a book through its experimental tactics and inflammatory design. The visual aspects are intentional, not clever, not inserted to camouflage bad writing or pad an impoverished page count. The threat of the title is exciting, the stories are wild, and yet the emoition I’m ultimately left with the is grief.

I want to end on a high note so you’ll read this book. I’m also not going to lie to you: when I read Yeager, I’m overwhelmed. I have to walk away—and I mean physically get up, go outside, find a lake or a copse, and reorient myself in the here and now— to process his work because it stirs memories and associations I thought I’d put far behind me.

Except I don’t really believe that. I think our grief becomes part of who we are, and we come back to it cyclically. Like seasons or tides or symphonies, grief goes through recognizable movements while altering subtly over time as long as we deal with it. Right now in America, we’re sitting on a mountain of pandemic grief, except the mountain is a volcano, and we’re pretending the volcano isn’t there.

Burn You the Fuck Alive is a moving and truthful book, despite its violence, because of its violence, because America is a land of violence. If you’re ripe for an unsafe text to stir You from your stupor or complacency, I recommend spending time letting the visuals sink into your subconscious and, if possible, reading the physical edition to savor the threat to its full extent.

Joe Koch writes literary horror and surrealist trash. Their books include The Wingspan of Severed Hands, Convulsive, and The Couvade, which received a Shirley Jackson Award nomination in 2019. His short fiction appears in publications such as Vastarien, Southwest Review, PseudoPod, Children of the New Flesh, and The Queer Book of Saints. Joe also co-edited the art horror anthology Stories of the Eye.

More Reviews