There were giants in the earth in those days; and also after that, when the sons of God came in unto the daughters of men, and they bare children to them, the same became mighty men which were of old, men of renown.

—Genesis 6:4

In our family there were two instruction manuals—the Old Testament and the stories of the Old West—and it was often difficult to tell what, if any, difference lay between the two. If we weren’t in church, we were watching Gunsmoke, and in the high heady days of my childhood, I came to believe that Christ likely bore a closer resemblance to Marshal Dillon than to a long-haired bestower of boons. After all, one might preach just as well with a pair of six-shot Colts as with the Gospels. Did not Christ declare that he came bearing a sword? And why wouldn’t a manifestation of God walk with an easy lolling shuffle and speak in a John Wayne baritone soft as saddle soap? These seemed facts beyond dispute.

Among my tutors at this early hour of life were not only Sunday school teachers, but also my grandfathers, both of whom had served during World War II. These were brusque, no-nonsense men of a sort now mostly vanished. Their values were hardscrabble, and they brooked very little foolishness, and it is to be counted among the Lord’s many blessings that they did not live to behold this most stupid of centuries. It is to be counted among the Lord’s many ironies that had they been a different sort of men, we might not even have this century at all, stupid or otherwise.

What wisdom they kept found its mythos in cinematic Westerns. My maternal grandfather, Guffie Morris, a booming US Navy veteran of the Pacific theater, loved in particular The Searchers, while my paternal grandfather, V. C. Taylor, who served in Europe, held a fondness for Zane Grey and A. B. Guthrie novels. These stories seemed to measure up to their own experiences somehow. It was not uncommon to hear them tell a war story and confuse it with something that had occurred in John Ford’s Monument Valley. The settings and scenarios might have differed, but the travail and epic scope were the same—how do good men bear up beneath the yoke laid upon them by a suffering world?

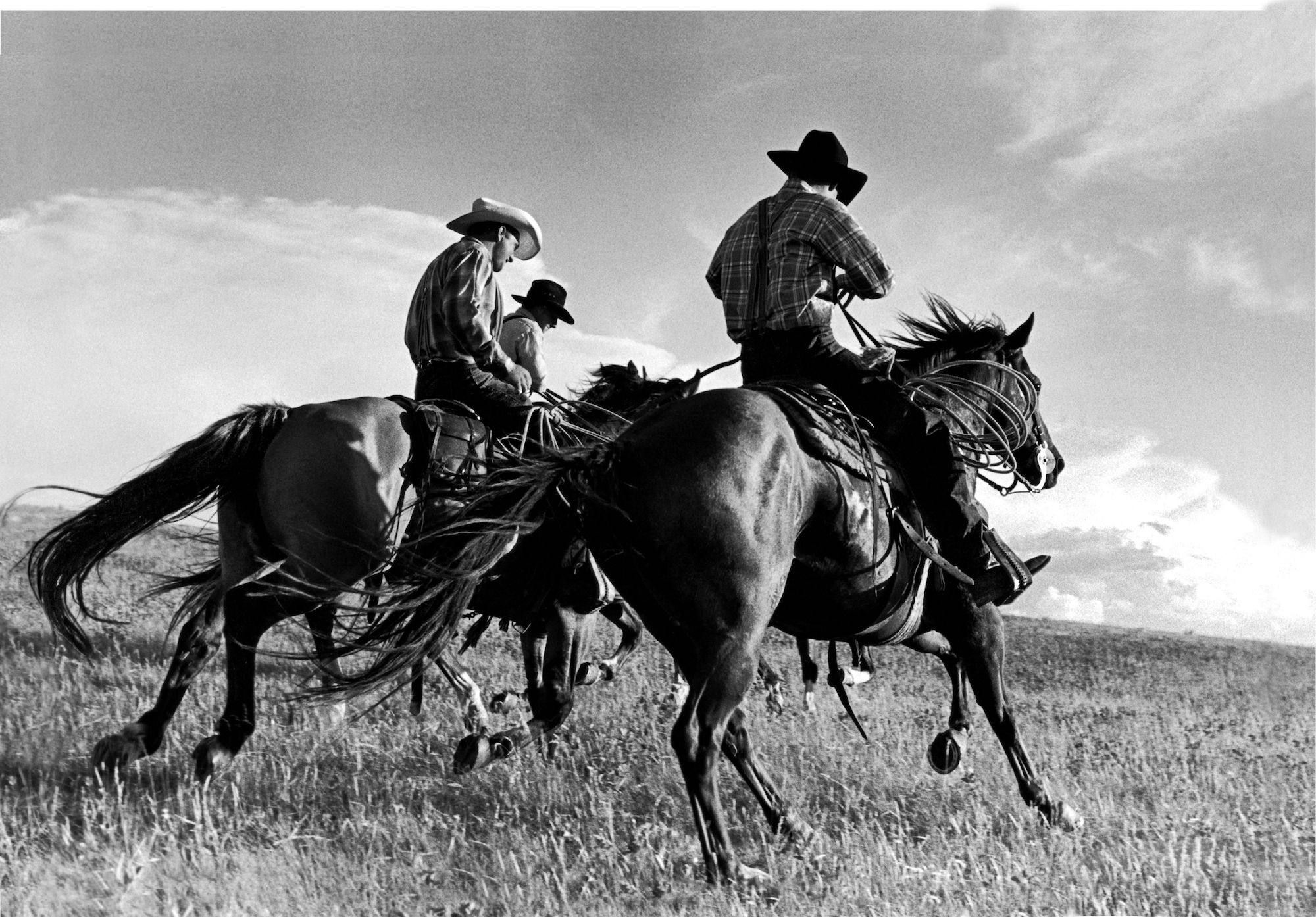

For them, the West as it was wrought in the piebald dapplings of a sepia sunset seemed rightly grim, and if they were given to brazen, boyish hooting at the sight of John Wayne riding across the screen, it was because the stories of the West redeemed all the tragic horrors of the twentieth and most woebegone century. To see horses unfurling at manifest speed across the wide, yellow plains seemed to set them once again at peace, for they had seen the hand of God and knew its quick and terrifying penmanship.

Among the Westerns that most captured their reverence was Lonesome Dove.

In 1989 the dramatization of Larry McMurtry’s eponymous novel ran on CBS over the course of four nights. Both my grandfathers loved it. So did the rest of my family, but I recall watching it with these two old men and feeling little different than I did when I sat next to them on a church pew. Something close to prayer seemed to be happening between us as we watched Gus and Call drive a thousand steers from Texas to Montana, and when the final frame faded, I expected someone to say “Amen.” Perhaps they did, if only in their hearts.

Once Lonesome Dove ended, it became something of a talisman in our household, referenced at moments of both pathos and high brio. At the funeral of my great-uncle Ulysses (called Useless by those who knew him best), I heard more quotes from the miniseries than I did from Psalm 23. My grandfather Guffie would spit lines from the show at the dinner table or after church. Knuckling my towheaded scalp, he’d recite the choicest snippets of a story he considered holy. “I god, Woodrow, in twenty years we’ll be the outlaws,” he’d say. Or, if my grandmother was in a particularly vexing mood, he might pipe in with “My wife is in hell where I sent her. She made good biscuits, but her behavior was terrible.”

As with all things, my paternal grandfather V. C. was less forthcoming with praise for Lonesome Dove, though he did love it. Like Guffie, he’d been involved in the great World War II, enduring some of the fiercest fighting in the Ardennes Forest during the Battle of the Bulge, and there are in my possession, along with his Bronze Star, several faded Nazi armbands to prove it. The experiences of the war left him taciturn, at times morose, at other times capable of legendary rages, and I have seen him snatch a pump gun off the mantle and then rush out into the moonlit barnyard to send a chicken-thieving fox into eternity.

In retrospect, it seems to me these two men were approximations of the sort embodied in Augustus McCrae and Woodrow Call. One was a boisterous man who loved to joke and sometimes pulled a cork, while the other was dark-eyed and brooding. Both grew up in poor circumstances difficult for a generation of digital natives to imagine, much less admire. They feared little other than God, though they were often baffled by their wives. They were unashamed of blood, but felt sex was something best not discussed. They were flawed, but not tragically so, and they had helped save a world that had turned its back on their values.

It’s little wonder that they saw something familiar, if only dimly, in the characters of Gus and Call. Like McMurtry’s fictional cowboys, they had gone out on their own adventures. They had seen the world and its troubles and knew that a great deal of them could only be solved by a bloodletting. They knew that evil was a real presence in our world, and that it was sometimes brought to heel through forces larger than any individual, or through the intervention of fate and happenstance.

Perhaps the best literature always gives us back our lives. We lose so much of ourselves in the threshing and winnowing that scant memories remain to give us ballast. So it is that we come to live more inside a story than in this world of glassy glances.

As they neared the sunset of their lives, this certainly held true for my grandfathers. Often, I would catch them watching the far distance, and I knew they were somewhere else, out riding fences and chasing the horses of their youth, singing in their bones the tales of a forgotten time as their blood raised a toast to the “sunny slopes of long ago.” One of the stories that seemed to stand up taller than the others was Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove. It returned to these old men something they thought had been lost in the moral desuetude of peacetime—namely, the thrill of adventure.

Paradoxically, as a writer, McMurtry was no adventurous stylist. In interviews he claimed to write between six and ten pages a day. These aren’t the habits of a man weighing each word, and to read a McMurtry novel is to forget that simile and metaphor even exist. In his weaker books—The Berrybender Narratives are an embarrassment—he seems to speed through his sentences as though running his finger down a shelf of nonperishables. The prose is stilted, canned, and bereft of music. His diction can often be repetitive and tedious, and he was far too prolific, publishing over forty books and scads of screenplays.

Even so, one can’t dismiss Larry McMurtry as a mere genre writer. He doesn’t belong on the ash heap of nigh unreadables such as Stephen King or Tom Clancy or Jim Thompson. His best books—Lonesome Dove being among them—are as fine a rendering of human frailty as anything penned by Chekhov. Who doesn’t weep during the death scene of Emma in Terms of Endearment? And who isn’t torn to their core when Gus and Call are forced to hang their old companion Jake Spoon? These are moments when the reader is given back, with startling clarity, their own life.

Of course, McMurtry is more Hank Williams than he is Russian master. Anyone who has stood alone in a moonlit field in Texas and heard the wind go singing through the barbwire and the sage grass understands something about “The Lovesick Blues,” that heartache is given special emphasis in our lives so that we may be startled by love and perhaps awake to its promise, or grieve its absence. They also understand a great deal about the lonesome world of Larry McMurtry. In novels such as The Last Picture Show and Horseman, Pass By, he renders, perhaps better than anyone, the yearning of youth and love’s lingering failure, but in notes drifty as the skies above Archer City. If Chekhov found a metaphor in the cherry blossoms of Melikhovo, McMurtry found one in the flinty light of the Texas panhandle, a light that seems to make everything, even the people, hard and thin as tintypes.

The soil made McMurtry’s oeuvre, and he never forgot it. Even when accepting an Oscar in 2006, he wore Wranglers and boots and a bolo necktie onstage. There’s a bit of the defiant Jim Bowie in such a gesture, and we should applaud it. McMurtry cared deeply about where he was from, and he wanted us to care as well.

In a frivolous age, place counts for naught. We live in blips and blinks, scattering from one nameless exit to the next, never deigning to know our towns. Why look at the mountain or the oak when one has the blessed Tubes of You? If everything is disposable, why not also discard one’s roots? Better yet, pluck them up from the dirt and cast them like tares onto the fires of repudiation. And there are considerable social rewards for such destruction, at least among the literati. It is lauded as bravery and a sign of sophistication. But this is a fantasy. Soon, its sweetness turns to gravel in one’s mouth. The deracinated man finds himself adrift, unmoored from any coherent ethos. He harbors no sense of obligation toward the future, nor can he take comfort in the bequest of his ancestors, who, by today’s pious standards, were all benighted ogres.

The late philosopher Roger Scruton coined the term oikophobia to describe this phenomenon, oikos being the Greek word for home. If, so the logic goes, we repudiate our homes, then whatever sins might have occurred there cannot be laid upon our souls, and in signaling our own escape from the demands of a place, we believe, foolishly, that we will be granted entry into the elect kingdom of Nowhere. But, as Scruton points out, this leaves us in a spiritual desert.

The greatest writers are all writers of somewhere. The longer the shadow place has cast in a writer’s heart, be it Flaubert or Flannery O’Connor, the more enduring their creations, and part of their artistry lies in the fact that the place is remade in their image. Who can watch a Mississippi sunset and not think of Faulkner? Would we even notice it without Light in August?

For all the personal—and even artistic—ambivalence McMurtry might have felt toward the Lone Star State, it was the place he chose to set most of his work. It was also where he chose to live and to die, perhaps because he had helped to shape not only our understanding of Texas, but also our fantasies about it. Perhaps we wouldn’t even conceive of Texas at all without Larry McMurtry.

The writer Susan Sontag once quipped, regarding Archer City, that McMurtry lived in his own personal theme park. Steeped in the McMurtry mythos—the residue of Hollywood lingers in the air in a haze of brittle, deep-fried tinsel—the town, with its many McMurtry-owned bookstores, seems more like Thalia, the fictional hamlet of The Last Picture Show, than it does itself. There’s a bit too much self-ogling, and a bit too much hamming it up—all of it based on the success of Larry McMurtry—but this seems to be the way of literary towns.

Yet beyond this schlock searches the brisk and quickening wind. When we hear it sawing through the chaparral, we think of Duane and poor Deets, Lorie and Clara, Newt and Pea Eye. They never existed, yet they stand taller than a noontime shadow in the dusty dun-colored day. Though McMurtry expressed antipathy toward the cowboy mythos, it was larger than his own personal vanity. It endures. It stands up, sturdy and true, helped along by the novels written by a son of the Texas soil. How else to explain the way my grandfathers—two men who’d gone to war—loved McMurtry’s books? These weren’t disillusioned soldiers, but the sort who still believed in the old verities, rough-hewn as they were. It is more than a passing irony that some of McMurtry’s most ardent readers were just this sort—cowboys of the twentieth century—whose ethos he admitted in interviews to finding a bit hollow. The more one ponders on this, the more one is reminded that writers and poets know little to nothing about the hoi polloi—and that there is indeed a divinity that shapes our ways, and more in heaven and earth than in all our philosophy.

For all his reputation as a writer of gun sagas and adventure, McMurtry must, at the final reckoning, be deemed a man who did not destroy the myth of the West—writers are never so important as they think—but one who composed its epitaph. The small towns of McMurtry’s youth were already dying by the time he grew to manhood, and the cattle drives he heard yarns about were at least three quarters of a century gone. Even so, in the sifting, sandy winds, he must have caught the lingering air of a larger, more noble time, and perhaps heard singing, each to each, the shadows of heroes, their voices growing fainter with every passing year. And he must have loved those times and those people. Why else devote his life to their study, and to telling the truth about them?

Read in its entirety, McMurtry’s corpus seems a chiseled remembrance of the West as it was, ought to have been, and will be no more. Seen in this light, novels such as Lonesome Dove and Streets of Laredo don’t demythologize the West, either as reality or genre, but sing its funeral dirge. They offer both praise and pity for the men and women who settled the North American continent during the 1800s, an era of brutality and racial animus, to be sure, but also one when dignity and grit, gumption and heroism were not only common traits but ideals to which people aspired without irony.

Of course, it must be said that the song heard at eventide in the West is a plaintive one. For McMurtry, the West was as much about dreams that didn’t turn out as it was about manifest destiny. If a thousand men made their fortunes under the big sky, how many sundry others fell into the ditch of absolute failure, killed by a Comanche’s lance or scalped by the Sioux just west of St. Louis? As the West was settled, a flux of unimaginable savagery washed over the land, drowning out many of the native cultures who had lived on the continent for millennia, who in turn visited vengeance upon many innocent European immigrants.

Such grand upheavals plow up fertile soil for burgeoning myth, but also for pathos, and McMurtry, for all his humor, never tired of reminding us of the fleeting nature of life. Our years pass as a vapor and man is born to trouble as the sparks fly upward. Even so, there is a sweetness to loss that only the truly bereft know. As Gus reminds Newt in Lonesome Dove, the earth is mainly just a boneyard, but pretty in the sunlight.

This sentiment is too easily derided as nostalgia. But what is nostalgia but praise for what one has loved, and loving it with all the more vigor because it has been lost. It is the same sentiment intimated by Basho in the seventeenth century when he wrote, “Even in Kyoto / Hearing the cuckoo’s cry / I long for Kyoto.” It is echoed in Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, wherein the life of man is described as the flight of a sparrow through a mead-hall. And we find it in the works of Larry McMurtry. From dark to dark and winter to winter, the bird of time ever darts away, and to read McMurtry’s finest books is to hear the old sorrows wing down the ages and know how they have brought the hoarfrost of wisdom to the brows of sages and seers.

Is it too much to suggest that McMurtry ultimately perpetuated the old myths he sought to destroy? I don’t believe so. In fact, one can say that this was his greatest, if accidental, accomplishment.

Larry McMurtry, for all his grousing about the West and cowboys, for all his pretensions, wrote books my grandfathers spoke of with the same fondness they accorded to their oldest and truest friends. I believe he helped these men die a little better than they might have otherwise. And he helped those of us left behind remember our own losses so that we might grieve.

In remarking on McMurtry’s death, I am reminded of one of the most poignant scenes in Lonesome Dove. During the fording of a river, one of the cowboys, a callow Irishman, is killed when he swims his horse through a nest of water moccasins. As the rest of the Hat Creek gang buries the poor boy in a narrow grave by the riverside, Augustus doffs his hat and offers a eulogy. “This was a good, brave boy,” he says. “He had a fine tenor voice, and we’ll all miss that. . . . Let’s the rest of us ride on to Montana.”

We will all miss McMurtry’s voice. But there are trails yet to ride, and I’d like to think McMurtry would admire those who will blaze them. Adventure, after all, is still a noble and dignified tradition, one worthy of our praise and our efforts to uphold its practice. ![]()

Alex Taylor is the author of three books: the story collection The Name of the Nearest River, and the novels The Marble Orchard and Le sang ne suffit pas. A recipient of the Chaffin Award for Appalachian Literature, he teaches at Morehead State University and lives in Grayson, Kentucky, with his wife and daughter.

Photo: Laura Wilson