For Francisco Olmeda, Halloween was the gateway to a life spent studying spooky things. He was seven when he asked his mom about the story behind the mummy costume she got him at Goodwill. His mom, Eloiza, didn’t know much about mummies, so she mumbled something in Spanish about the Egyptians and then told her son she’d take him to the library that coming Saturday. Eloiza worked at a restaurant and Francisco’s father, also named Francisco, was a mechanic. They called the older Francisco “Paco” to differentiate father and son. Eloiza and Paco hadn’t gone to college, but they eagerly pushed books on their son and had taken him to get a library card the previous year. The books worked. They made Francisco curious about everything, and his thirst for knowledge often backfired and put his parents in a weird spot where they were forced to make a decision: lie or accept that they had no idea. Whenever that happened, they went to the library.

Back then, Francisco thought librarians were geniuses that were given jobs at the library because they knew everything, or at least knew which book had answers to your questions. The pre-Halloween trip to the library was short, but Francisco went home with three books about mummification. Learning that his costume was based on something real blew his mind. If mummies were real and his grandma back in Puerto Rico was, according to his father, a real witch—“a bruja, but not like the ones in the movies”—then what was the story behind things like werewolves, zombies, vampires, ghosts, and demons?

Francisco wore his mummy costume for an event at school that week and then again on Halloween night, which fell on a Friday. He went trick-or-treating with his three best friends, David, Sebastian, and Abe, and told them about how Egyptians placed major organs in canopic jars to preserve them but thought the brain was useless, so they used a hook to pull it out of the skull and then got rid of it. They talked about cutting bodies open and using different tools to yank out a brain through a corpse’s nose as they ate an unhealthy amount of candy. The next day, Halloween was over, but for Francisco, it never ended.

As the boys got older, they developed unique interests, but they stayed friends and had enough interests in common to become brothers. David excelled at sports and his parents hoped he’d go to college on a tennis scholarship. Sebastian got into cars and wanted to become a mechanic. Abe loved comic books and got into video games, which meant that for two years all they did was stay in his room playing Street Fighter II: Special Champion Edition on his Sega Genesis and eating pizza. Francisco studied spooky things. He read true crime, books about haunted places, and horror novels like they were going out of style. Once he discovered the internet, he spent time reading about the paranormal and studying videos of ghosts and strange creatures caught on camera with the same passion other kids showed for the kinds of websites their parents didn’t want them to visit. He was always looking for answers to the weird, the creepy, the mysterious. He constantly pursued the feeling he’d gotten from learning mummies were real.

The first thing Francisco learned is that there is usually a truth behind every horror story, every urban legend, every old wives’ tale, every spooky thing whispered among kids to scare each other to death while roasting marshmallows around a camp fire. He spent a lot of time looking into the horror stories everyone knew in Madrigales, his hometown. With enough time online and in the library, where Becky, the main librarian, happily got him as many interlibrary loans as he needed, Francisco carefully dismantled every supernatural narrative and every urban legend he came across until he got to the nugget of truth at its core. For example, people said the I-83 tunnel out of town was haunted by the ghosts of children. It wasn’t. The story came from a school bus that crashed there in 1962 while taking kids on a field trip. There were a lot of injuries, but no casualties. Francisco found it all in the microfiches of the Madrigales Gazette, the local newspaper. One of the kids, Alberto Davidson, worked at the post office and was on friendly terms with Paco.

Folks also claimed that at night a dark figure roamed the old Madrigales Cemetery, which took up a lot of space on the east side of town; it had been seen by many residents. That was true. An Italian immigrant named Luca had worked as the caretaker there for almost five decades, until his heart exploded while he was digging a grave. He slept during the day and walked around taking care of business at night because he claimed the sun hurt his skin. It was a creepy story about an eerie place, but not a haunting.

While Abe, David, and Sebastian never read the same books or shared Francisco’s passion for unnerving yarns and urban legends, they enjoyed learning about them. They also loved telling Francisco about any new scary tales they heard because he always knew the story behind them or would spend weeks looking into it and then would share whatever he’d learned. In all their years doing it, they had found two stories that were real, or at least appeared to be. The first one was the Crying Girl, a disembodied voice that could be heard around Johnston Street, where a somewhat recent row of houses stood against the back of the local grocery store. Construction workers talked about how they always got out of there before the sun went down because as soon as it got dark, they could hear it—the sound of a young girl crying. After the houses were finished and they went on the market, the stories proliferated, and the folks who moved into those new abodes corroborated them. There were plenty of videos about the Crying Girl on YouTube, as well as a thousand theories on as many websites, and a TV show had once come to town to spend a night recording the crying and looking for its source. They got a lot of great audio, but couldn’t solve the mystery. The ghost of a sad girl really walked around Johnston Street at night, and that was enough to keep Francisco looking, digging, and reading.

The second real story was the one Francisco obsessed about the most, and it was the one they wanted to figure out before life pushed them closer to adulthood than they wanted to be and college became a thing between them instead of a communal dream. The second story was about the entity rumored to inhabit the woods to the south of Madrigales, an area the locals called “the woods” and maps claimed was officially called the Westcave Nature Preserve.

According to a book Becky had gotten Francisco—and thirteen articles of varying length published between 1981 and 2009 in the Madrigales Gazette—six government workers, three Madrigales families, and the nine kids and two adults that made up Boy Scout Troop 413 had gone missing in those woods. The Boy Scouts story went national. According to experts, the Westcave Nature Preserve wasn’t big enough for people to get lost in it forever, so conspiracy theories grew up around it like mushrooms after three days of rain. A cabal of Satanists operating in or near Madrigales had kidnapped everyone in order to sacrifice them to the Devil. An international ring of sex traffickers had beaten the Satanists to the punch and the kids were now in basements and dungeons in “evil” countries like Russia and Saudi Arabia. Aliens had abducted them and taken them to some faraway planet to conduct experiments on their bodies. A serial killer lived in those woods, hiding in a tiny cabin no one had seen. The list went on and on. The truth was this: none of those people were ever found.

Francisco had a few ideas, and none of them made him comfortable. You could blame a disappearing family on a killer, but the nine boys and the construction workers were a different story. According to the articles he read on microfiche, weird things started going on when the government decided to slash into a corner of the woods to make the construction of I-83 easier. Equipment malfunctioned regularly, things were moved around, and tools went missing during the night. They placed a cyclone fence around the machines and placed a guard in a little wooden shack outside the entrance. The guard went missing the first night he was there. After the second guard suffered the same fate, they couldn’t find people to work that gig. Because they wanted to beat the heat, workers on the site started so early it was still dark. At the end of the second week, a worker vanished on his way to a bathroom break. Three more followed, with one vanishing from his tractor while operating it, which caused a lot of mayhem and made the news. As quietly as they’d come, the workers left, and I-83 now skirted around the east side of Madrigales like it was trying not to touch it.

Francisco had been collecting books, articles, and videos about the Westcave Nature Preserve for almost a decade. He could find no explanation that satisfied his curiosity, and now that August and his move to Austin to go to college felt like something barreling at him at top speed, he wanted to spend a night there.

The thing about the woods is that Madrigales residents seemed to think that not talking about what happened would make it go away. Francisco knew things didn’t work like that. But he also understood that most people had an aversion to the kinds of things he was naturally drawn to. In a way, he knew he was the weird one, not the other way around. Bringing the story up with his parents never led to anything positive. The same happened to Abe, David, and Sebastian when they asked their parents about it. For years they had talked about walking a couple miles into the woods and camping there for the night. They never asked for permission to do it and knew that lying and trying was too risky. Now they would be away from each other for the first time since they met at school, and they understood it was now or never. They had all graduated high school, so vanishing for one night wasn’t as hard. Sebastian and Abe had cars. They could pull it off.

Eloiza and Paco were in Francisco’s head as they all shouldered their backpacks and began to walk into the depths of the Westcave Nature Preserve. He could hear his parents, could feel their disappointment if something happened to any of them. The woods were bad and you didn’t go there at night. It was easy to understand that, an easy rule to follow.

“Never asked you, man,” said Abe. “Why the hell do they call this Westcave? Is there a cave in here?”

“Nah,” said Francisco, happy to be distracted. “One of the theories says there is a cave around here and that a creature lives in it. They claim that’s what came out and ate or . . . you know, did whatever to make all those people disappear.”

“And how do we know there’s no damn cave?” asked David.

“We know because the government had to check for them before they started trying to construct a chunk of interstate here. They used radar that goes into the ground and shows if there’s a hole in there. They didn’t—”

“Okay, so here’s the question: What do you think is here?” asked Sebastian. For that, Francisco didn’t have an answer.

Abe and Sebastian stopped walking, their eyes on their horror-loving friend.

“You don’t have a clue? Are you for real?”

Francisco looked at Abe. The knot in Abe’s brow spoke volumes. Francisco knew they expected more. They were here on an adventure, but he knew that in their heads, the adventure wasn’t dangerous because Francisco always knew the truth about things, and if he brought them here, that meant there wasn’t anything truly horrible out there.

“I don’t have a clue,” said Francisco. “But listen, I’m going away in two weeks and David is heading up to NYC in a few days because practice starts before his classes do, so this is the last chance we have to get in here together until god knows when.”

With that, they walked on.

As they made their way deeper and deeper into the woods, Francisco’s mood changed. His nerves subsided and his love for his friends took over. They were ride or die friends before they even knew that was a thing. You picked on one of them, you had to deal with all of them. They loved each other the way only people who grow up together can love each other. He was happy about moving to Austin and starting his journalism classes . . . and the anthropology classes he’d managed to work in there after explaining to his advisor that he planned on pursuing anthropology once he was done with his BA. But he was going to miss these guys. He was going to miss them a lot.

Over the years, Abe’s love for video games and pizza had caught up to him. His body filled out, and then it kept expanding. When he stopped, sweat plastering his light brown hair to his forehead, they all stopped.

Setting up didn’t take long. A hundred nights camping in each other’s backyards and with their parents by the river on fishing trips meant they were very familiar with the process.

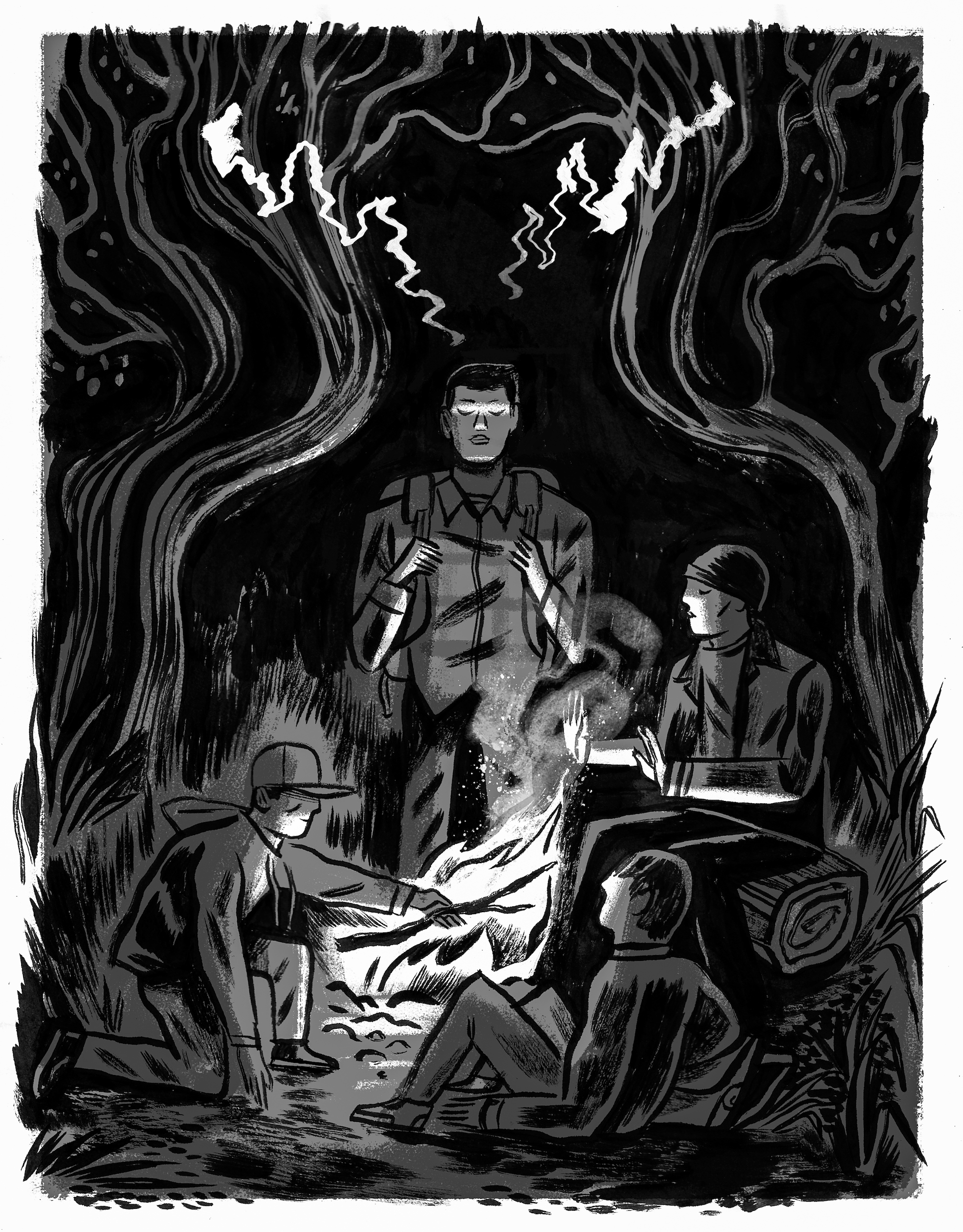

An hour later, the sun had gone down, and the darkness around them, which the fire they’d gotten going struggled to push back, had come alive with the sounds of insects and small things scurrying around.

Whenever Francisco, Abe, David, and Sebastian got together, their conversations became a living thing that constantly shifted around and went from sad to hilarious to insulting to dirty to profound. Francisco knew this time it was all that, like always, but it was also special. It was special because they were all hurtling toward different futures in different places. He knew this magic was about to end, and the thought was strong enough to fill his eyes with tears. Luckily, the smoke occasionally flew his way, which gave him an excuse to pull his shirt up and wipe his face.

David was saying something about roasting hot dogs over the fire when they heard a twig snap. The sound was loud enough to soar above the rest of the night noises surrounding them. They all went quiet and looked around before searching for reassurance in each other’s eyes.

Abe opened his mouth to say something, but a sound akin to the hiss of a city bus’s breaks interrupted him. Unlike the snapped twig, this sound came from a specific spot in the darkness, and they all looked in that direction—right behind Sebastian. In the darkness caused by the night and the dancing shadows of the trees, something darker moved, something long and tall. Francisco thought about pulling big catfish from the bottom of the muddy river, their bodies a black smudge emerging from the coffee-colored water, a thick, solid dark within more darkness.

Fear was something Francisco had read a lot about. He also knew fear because he had felt it before. He’d been afraid of getting caught, afraid of the dark, afraid of bad grades. This, however, was a different kind of fear; this was fear of the unknown, and it felt like a strong person was squeezing the back of his neck.

The four friends watched as the shadow in the darkness came together and coalesced into something undeniably physical, something they knew they could touch. Then the thing in the shadows moved into the space illuminated by their fire; an impossible column of ink-black darkness that stood about fifteen feet tall. With another hiss, a hole lined with teeth emerged from where the thing’s head should have been, and tendrils of what looked like thick smoke erupted from its sides and writhed in the air like electrocuted worms.

Sebastian screamed. The sound pierced through the air and shook them all to the core. They jumped to their feet in unison.

The thing in the shadows moved again, descending on Sebastian with a quickness that belonged to something much smaller. The thing’s movement made Francisco think of liquid running down a window. Abe, David, and Francisco watched, frozen in fear, as the thing that had emerged from the woods’ shadows stretched the hole lined with teeth and swallowed their friend whole.

The one thing Francisco had never read about is how fear can scramble your thoughts. They all ran, scattering in different directions like cockroaches under a bright light. They had no plan, but in that moment, being away from that unholy column of death was enough.

Francisco stumbled and fell twice, but the adrenaline pumping through his veins made him jump to his feet and keep running. He wondered if he was running toward a road or a house, some kind of civilization that could translate into salvation. He was gulping air and blood was pounding in his ears, but he knew stopping was not an option. Somewhere to his left, a scream cut through the darkness. It was a panicked, desperate sound. It was the sound of terror clashing against a real monster.

A rock or a root grabbed Francisco’s left foot and pulled him down to the ground. Fire flared in his ankle. He tried to stand up, but the pain was too much. From behind him, the hissing sound came again, and it sounded as close as it had when they were all around the fire.

Francisco turned to the noise and something else tripped him up and landed him on his ass. The towering darkness was there, not ten feet away. The fear he’d been feeling suddenly vanished like Sebastian had; there one second, gone the next. In its place, a heavy sadness flooded Francisco. Time didn’t slow down, but his thoughts traveled at the speed of light. He knew the sadness came from lives cut short way too early. It came from shattered futures that would never be. It came from his friends no longer being with him.

The hole lined with teeth expanded and a choke escaped from Francisco’s throat. Here was his answer, the last one he’d ever get. A second before the thing descended on him, Francisco realized the worst part of looking for answers is that sometimes you get them, and that sometimes it’s better to let creepy stories just be what they are. ![]()

Gabino Iglesias is a writer, professor, editor, and book reviewer living in Austin. His most recent novel, Coyote Songs, was nominated for both the Bram Stoker Award and the Locus Award, and won the Wonderland Book Award for Best Novel in 2018. His nonfiction and book reviews have appeared in the New York Times, NPR, the San Francisco Chronicle, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and other venues.

Illustration: Mike Reddy