On Saturdays Angela would arrive at her grandmother’s house with the groceries she’d requested (mostly candy and ice cream) and some sort of treat—scratch-off tickets or a CD audiobook or a box of kołaczki from the out-of-the-way Polish deli.

Angela put away the groceries, and her grandmother poured her a glass of chocolate milk on the last day of its life, which Angela pretended to drink as her grandmother got down to business.

“What does this say?” she asked, handing Angela a piece of cardstock.

Angela looked at the high-speed Wi-Fi flyer and said, “It’s trash, Tookie.”

“What is it though?” her grandmother insisted.

“An ad for the internet,” Angela yelled. Her grandmother’s hearing was nearly gone. She’d gotten hearing aids as a part of a senior support initiative close to a decade ago—she was entitled, she said—but hadn’t put them into her ears a single time. She’d gone through the steps to get a flip phone, too, but never turned it on. Tookie didn’t have a computer though, so the internet was useless.

“Well, that’s trash! Throw it away!” she said, ripping the card in half and putting it in the broken-lidded can beside her. “And this? I think it’s my property tax. Is it my property tax? How much?”

Angela looked over the bill. Her grandmother was right. She didn’t know how she could tell. Context clues, she guessed. Over the past decade, macular degeneration had slowly taken all but the very periphery of her grandmother’s sight. For the majority of her retirement until then, her grandmother had read a book a day. “Bring me that witch book,” she’d demanded of Angela when the Harry Potter books started making the news. And then, “I don’t get the fuss. Do you get it? Did you read it?” Angela had taught her grandmother to use a portable boom box, and then started checking out every audiobook in the library, five at a time, for her grandmother. If she brought a repeat, her grandmother blamed it on the authors. “All these books sound the same. Nothing surprises me.”

Angela shrugged and eyed the stack of tabloids her grandmother still received in the mail. Her grandmother read the headlines and circled the stories she wanted to know more about with a big black Sharpie. Angela hadn’t been able to visit the previous weekend, so the pile was larger than usual.

“Well, how much?” her grandmother asked.

Angela remembered the bill in her lap. “Two thousand, for six months,” Angela shouted.

“Highway robbery!” Tookie exclaimed. “Write the check.” She pushed her checkbook to Angela, who dutifully wrote the amount, pointed to the line where her grandmother should sign her uneven scrawl, and balanced the register. She dug through her grandmother’s pile of papers for a stamp.

“Tabloids?” Angela asked.

“Brad Pitt is up to something,” her grandmother said. “And I need to know about this cancer cure they’re making from bug stuff.”

Angela smiled and hunted through the pages for these two stories, none of it reliable. Her grandmother was sharp and practical, but she also had an insatiable appetite for gossip. Angela admired Tookie’s contradictions.

Her grandmother paused. “I have one more thing to ask you.”

“What?” Angela asked. These interactions, where her grandmother had a question to which she didn’t have an expectation of the answer, could get hairy sometimes. With standard conversational back-and-forth, her grandmother could anticipate. She could formulate her questions to receive yes or no answers, but when she needed a lengthy explanation, her lack of hearing made things especially difficult. No matter how clearly Angela explained herself, she’d have to repeat it several times, in different forms, to make sure Tookie understood. She could feel both of them steeling themselves for one of these complicated exchanges.

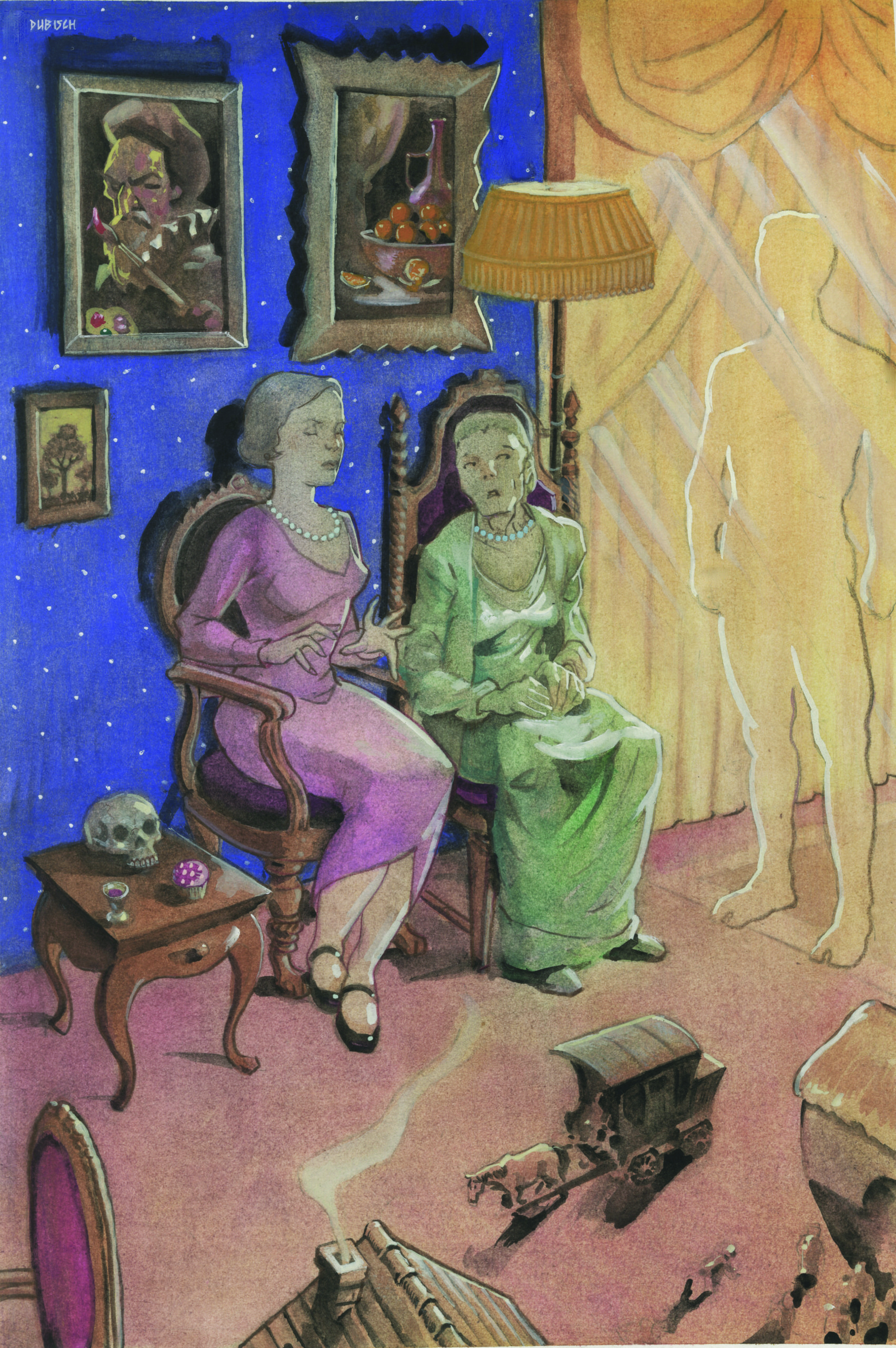

“Now listen carefully,” her grandmother said. “Someone is projecting pictures in here through the windows, like movies. I’ll shut my eyes for a little while, and then when I open them, I’ll see a naked man in the dining room. Totally naked. It’s disgusting. Or I’ll see a little country town, from above, and all of the people are down there running around with their horses and buggies. It looks just like a scene I remember from a movie.”

Angela’s stomach dropped. This was new territory for Tookie. Was this the beginning of dementia? Her grandmother refused to leave her house. She had pledged to die there at all costs, and Angela and her mother had tried to make it work as best they could between them, but if Tookie became a danger to herself or her neighbors, all of this would have to end.

“I know who must be doing it, too. It’s their son next door. He’s mad that I told him he couldn’t park his car in my garage anymore, so he’s getting back at me. But how do you think he does it?”

Angela couldn’t help but smile at the sensible way her grandmother approached what must be a hallucination. It gave Angela hope for Tookie’s sanity.

“I don’t know, Grandma,” Angela said. She wanted to stay calm. She wanted to affirm her grandmother, worried Tookie would get scared or agitated if she made light of what Tookie was claiming.

“Your boyfriend is a cameraman, right?” her grandmother asked. “Could he come here and figure it out? Maybe he’ll know how they do it.”

“I can ask him,” Angela replied. What she meant by that was that she would do some research about what might be happening to her grandmother and her mind. “I’m sorry, Grandma.”

“Well, don’t be sorry!” Tookie said, exasperated. “Just help me figure it out.” She laughed like it was no big deal. “Now come with me and tell me if you want any of this stuff.” Their visits always ended with Angela’s grandmother showing her a pile of items she no longer wanted, and Angela taking as much of it home as she could. She rarely kept any of it, but she understood that it made her grandmother feel good to help Angela and to slowly empty out her cluttered bungalow. Angela accepted a tiered gold cookie plate she actually liked, an industrial-size stack of Styrofoam cups, polyester sheets still in their packaging from the 1970s, a baggie of orphaned earrings, and a cardboard box of her deceased grandfather’s old dress shirts. Angela would deposit some of this in the can in the alley on her way to her car, and the rest she’d drop off at the Goodwill before getting back on the highway.

![]()

Angela avoided the topic of the visions with her grandmother for the next few weeks; she assumed maybe the pictures had stopped. Angela had filled her mom in, and they’d decided not to panic. They remembered the time when her grandmother swore that the upstairs tenant had been playing his guitar at all hours of the night, when the tenant crossed his heart that he didn’t have a guitar or even a radio. That period had passed and they hoped this one would, too.

![]()

One Saturday in late June, the first really hot day of the year, Angela arrived to find Tookie’s house shut up tight. “Grandma! Grandma!” she called. Angela had her own key to the back door, but she never wanted to startle her grandmother. The doorbell was too quiet for her to hear, so the best Angela could do was to begin shouting as soon as she opened the door.

Angela made it all the way to the living room without a response; it was darker than she’d expected considering the midday sun. All the shades were drawn, and her grandmother sat in her chair, eyes open, staring, but totally unaware of Angela’s presence, even when Angela waved in front of her face. Only when she gently squeezed her grandmother’s arm did Tookie give a little jump.

“Angela?”

“Hi, Grandma! Why don’t we open a window? It’s so hot in here!” she yelled.

“Sit down,” her grandmother commanded. “The boy next door is doing that thing again with his projector. I saw that naked man again. I shut all the windows and closed all the blinds, but the pictures are still getting in here. Did you talk to Ben about it?”

Angela had told her boyfriend about what was going on, but he’d of course agreed that the idea of a holographic projection was a tough sell. “He said he doesn’t think it could be a projection, Grandma, but he’ll come here to try and figure it out if that would help.” Angela had weighed the pros and cons of what she said next. “You don’t think maybe it’s just a daydream?”

“I’m not seeing things, Angela. I know you think I’m old and batty, but I’m not hallucinating.”

“I don’t think you’re batty!” Angela shouted. “I just think your eyes might be playing tricks on you!”

Her grandmother shrugged. “I see what I see. I’m not afraid of the man. I know he’s not real, but I am afraid of what that boy next door might do. I’m definitely not letting him rent the garage again, but how is he getting around the shades and the curtains with his movies? I don’t like it.”

“We’ll try and figure it out,” Angela said. “I brought you chocolate-covered strawberries. Let’s eat them before they melt. And I’ll carve up this cantaloupe for you, too. It’s perfect. You should try to eat it fast before it turns.”

Her grandmother hoisted herself out of her chair and followed Angela with her walker, decorated with plastic Aldi’s bags full of tissues and her wallet and whatever else she needed to cart from the living room to the kitchen.

Angela talked her grandmother into cracking a window, and they ate the strawberries and sliced melon while Angela wrote checks and organized the discs from last week’s stack of audiobooks.

“Bring Ben next week,” Tookie said. “He’ll know what to do.”

Angela smiled at the way her tough-as-nails grandmother still thought technological know-how was a skill held only by men.

![]()

Ben had met Angela’s grandmother before, but Angela still reminded him about the need for clear and concise explanations.

Her grandmother described what she saw again. “This week it was the village scene, but I haven’t opened the curtains all week. It’s been so hot that it’s good to keep the sun out, but I need to know how he does it if the curtains are closed.”

Ben walked around the house, looked at every window and mirror, and then sat down close to Angela’s grandmother. “I don’t think it’s a projection. You’d need a very strong light and a background. There is an illusion called Pepper’s Ghost—”

Angela shook her head. If he explained Pepper’s Ghost to Tookie, she’d become convinced that that’s what the neighbor was doing, but there was still no way. The windows were blocked. Her grandmother’s home hadn’t been fitted with angled panes of glass. The less her grandmother knew the better.

Tookie scowled. “I’m not asking you if I’m seeing what I’m seeing. I’m asking you how.”

Angela broke in and took her grandmother’s hand.

“My arthritis!” Tookie cried, and Angela loosened her grip.

“Grandma, I’ve been doing some reading. I read about something called Charles Bonnet syndrome. Your eyesight is going, but you still see things where they used to be sometimes. Kind of like if you lose a limb, but have phantom pain. You see things where there’s nothing, or you see blurs and your brain tries to understand them as something more coherent.”

Her grandmother’s face showed confusion, but she waved Angela closer and leaned in to listen again.

Angela explained three more times until, eventually, Tookie flapped her hands and pushed back in her chair. “You think I’m off my rocker.”

Angela didn’t. She felt sadness for her grandmother, for how real the visions must seem and how frightening that must be, and respect for Tookie’s attempt to rationalize what she saw.

“You’re no help at all,” Tookie said. “If it happens again, I’m calling the police.”

“Grandma, don’t do that. If they think you’re unwell, they might not want you to live here alone.”

“But maybe they can tell me what’s going on, or at least go talk to the boy next door and tell him to stop bothering me.”

Angela pulled up pictures on her phone. “Grandma, look at the quilt I’m working on.” She changed the subject and hoped Tookie wouldn’t call the cops, but there was no way to stop her.

![]()

The police called Angela’s mother that week, after responding to a call from Tookie. They’d knocked on the house next door, but the boy next door hadn’t even been in town the week prior. None of the windows lined up, and the space between the houses was too narrow. They reassured Tookie as best they could. Tookie had put on her best act, behaving respectfully and pretending like she understood the officers and agreed with their assessment. The police mentioned sending social workers for welfare checks, but Angela’s mom assured them that that was unnecessary. She and Angela would try to help Tookie understand.

![]()

Angela had trouble sleeping that week. Every time the phone rang, she wondered if it would be the police, summoning her to come calm Tookie down. But what Angela couldn’t stop thinking about was how her grandmother was alone for so many hours of the week. Angela couldn’t imagine the loneliness of it, and then, on top of that, the isolation of no one believing Tookie when she told them what she saw with her own eyes. Angela had offered to bring Tookie to live with her countless times before, but her grandmother valued what little independence she had left. Angela tried to conceive of a life in which she’d want to be alone and quiet for the majority of her time, unable to watch or listen to anything, just feeling and sensing the little bit still available to her in the noiseless dark of her own future. It wasn’t the choice Angela would make for herself, but that didn’t mean that it wasn’t meaningful to Tookie. Angela thought of the internet flyers that her grandmother would scoff at. “Who needs all that information right this second?” Tookie had asked once. “We don’t understand what we already know.”

![]()

The following weekend, Angela’s phone rang with Tookie’s number. “Are you on your way?” she whispered.

Angela said she’d be there in five minutes. “Why? Do you need something else?”

“No, but the man is here now. He’s in the dining room, just standing there. He has an armful of oranges this time. I’m not scared because I know he’s not real, but if you hurry, maybe you’ll see him, too.”

Angela drove as quickly as she could. She looked up at the sky, clear blue, wondering if a change in cloud cover could shift the light in the house and erase the image. She parked in front and glanced at the house next door, but there was no light coming from the side windows. Their shades were drawn just as tightly as her grandmother’s.

Inside, Tookie’s house was dark. Angela’s eyes adjusted and she found her grandmother in the dining room. “Angela, do you see him?”

Angela looked where her grandmother was pointing. She squinted, trying to see what was in Tookie’s mind. Her eyes tried to turn the light and shadow into a male figure, but all she saw was the arched entrance to the living room.

“There?” Tookie asked.

Angela paused. “I think I do,” she said. “I think I know what you’re talking about.”

“Yes, it’s fading,” her grandmother said. “When the sun is bright, it’s harder to see. You didn’t believe me. You all thought I was a crazy old woman.” Angela saw Tookie breathe a sigh of relief and turn to her granddaughter. “What do you have for me this week?”

Angela held up the net bag. “Sumo Citrus,” Angela said, and her grandmother gasped.

“Let’s share one now. I want to save one to give to the cleaning lady and maybe a couple as a peace offering to the neighbors. Kill ’em with kindness, right, Angela?”

Angela glanced back toward the living room as her grandmother pushed into the kitchen. She saw the stack of this week’s tabloid stories on the ottoman. She saw the pile of mail they’d sort through shortly, deciding what was worth their attention and what wasn’t. And then, for a moment, the light shifted, and Angela saw a pale figure in the archway, arms empty—maybe just a ghost of what her grandmother had seen. ![]()

Jac Jemc’s novel Empty Theatre will be published by MCD x FSG Books in February 2023. She is also the author of The Grip of It, False Bingo, My Only Wife, and A Different Bed Every Time. She teaches creative writing at the University of California San Diego and serves as faculty director of the Clarion Writers’ Workshop.

Illustration: Mike Dubisch