He kept everything: I even found one of those paper napkins from a bar in Mexico;

how a paper like that from 1975 made it to Blanes in 2006 says it all.

—Carolina López

For there is a wind or ghost of a wind / in all books echoing the life / there . . .

—William Carlos Williams, Paterson

“Of all the mysteries of the universe, none is deeper than that of creation.” This is the opening sentence of a lecture given by Stefan Zweig in Buenos Aires in 1941, having been invited at the suggestion of Jorge Luis Borges. It also opened my first essay, written in 2012, on the work I’d been doing in Roberto Bolaño’s archive over several years. It seemed an appropriate place to begin, and perhaps even more so now that I’m writing this from Buenos Aires, in 2023. An archive offers a glimpse into the enigmatic process of a writer at work, in the quietude of his or her study, drawing creatures from the naught; or what Bolaño famously liked to call “the abyss.” Shuffling through his papers, I could still catch the faint whiff of tobacco every now and then as I turned a notebook page. It brought me back to an image I’d read on my first train up from Barcelona, in Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler: the smoke of a huffing locomotive breaks the novel’s surface, curling round and clouding the sentences. Calvino paints a small railway station, like the one where I was in Blanes, just before dark.

My first encounter with the archive was on June 22, 2008. Carolina López, Bolaño’s widow, had closed the writer’s studio and moved his extensive library and papers to her new home. In the time between his death in 2003 and my first visit to Blanes in 2008, Bolaño’s reputation had exploded internationally. 2666 won the National Book Critic’s Circle Award in March 2009, translation contracts were burgeoning, film deals were in the works, Alex Rigola’s theatrical adaptation of 2666 had been a smash success, and academic interest was growing exponentially in several countries. Yet behind the scenes, the atmosphere surrounding his work was growing ever more tense between the estate, the editors, and diverse circles of friends. Bolaño’s posthumous success brought a period of jockeying, mythmaking, and gainsaying . . . the question loomed: Who gets to set the narrative? During those years, I used a pseudonym, kept myself out of the fray and far removed from anything other than the work itself; rata-de-biblioteca.

![]()

In her book Spontaneous Particulars: The Telepathy of Archives, the poet Susan Howe offers the image of a tiny manuscript fragment written by Emily Dickinson probably in late 1885, which she also wrote in a letter to her sister-in-law Susan Gilbert Dickinson: “Emerging from the Abyss, and re-entering it, that is Life, is it not, Dear?” Nabokov’s famous opening line in Speak, Memory—“The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness”—expresses the same idea but with an unsettling image. It could also be the subtext of a doodle I came across in Bolaño’s archive; a closeup of the center of a diagram, which is the structure of 2666.

The word text comes from the medieval Latin textus, meaning “thing woven.” Quoting Gertrude Stein, Howe writes: “What is the difference between a sentence and a sewn. What is the difference between a sentence and a picture. [. . .] A sentence is drawers and drawers full of drawings.”

In Bolaño’s archive, there are drawers and drawers full of doodles and maps and stories and sewns. Howe’s book is an ode to the material of archives and research libraries, where “a thought may surprise itself at the instant of seeing. Where a thought may hear itself see.” I turn a page and there’s Bolaño joking to himself about Jimi Hendrix’s “Voodoo Child,” calling it “Vudu Chile.” Here, a list of the music he listened to while writing the night before—Lou Reed, Chick Corea, Barney Kessel; or books he’d read recently—Freud, Jacques Lacan, Hart Crane, William Burroughs, the troubadour Guiraut de Borneil; or notes for the war games he had played lately: Waterloo, Stalingrad, Third Reich. I find the drawing of a colander filled with spaghetti and it takes months before I realize it was a doodled allusion to Alfred Bester’s story, “The Men Who Murdered Mohammed,” from which he took the name and idea for the Unknown University: “A genius is someone who travels to truth by an unexpected path. [. . .] Nobody knows where the Unknown University is or what they teach there. It has a faculty of some two hundred eccentrics and a student body of two thousand misfits—the kind that remain anonymous until they win Nobel Prizes or become the first man on Mars.” We prepared a video for the exhibition of his papers, Archivo Bolaño, 1977–2003, with a playful rendering of a piece of spaghetti quoting a verse.[1] There was a list of lovers with nicknames.

There are objects that carry the author’s pneuma. There are pages where something may reveal itself at the surface of the visible; phrases Bolaño jotted on a page while overhearing a conversation at Estrella de Mar campground; words once carried on the wind, scattered, harnessed through a pen and fixed to the page. What were the shapes of the clouds that Funes the Memorious could remember on any given day? A mystery, he never described them. An archive carries you to a moment at the instant it alights, as it’s being pinned like a butterfly in a collection. Howe describes it as an almost mystical form of documentary telepathy. Time in an archive is specular; you read someone bearing witness as it unfolds, increment by increment, but you are outside of time. Capturing the writer in a spontaneous act, a thought on the cusp, a thought as it visits and is swathed in the new skin of language. An archive is physical, material. There is the smell of stale tobacco, the tea stains, the pen that is running out of ink, the pencil tip that has just broken or punctured a page in a moment of what? Passion? Anger? Excitement? Plenitude? It came so quickly, that idea, it could hardly be written out; or the second thoughts, a scratched-out word, the marginalia, a phone number, a name. And there’s the thought that was given volume, or spatialized into a doodle, given a geometric form, or that comes from an opposite direction, an enigmatic mathematical equation: Are they the numbers of words, of sentences, of pages?

“If you are lucky,” Howe writes in Spontaneous Particulars, “you may experience a moment before.” The metaphysics of an encounter with another person’s creative cosmos is where time lets loose and the past invades the present moment like a wave. Working in an archive feels at times like plucking tidbits from that abyss and dangling them over a newfound present. Diagrams of triangles, stars, hexagons, circles. What do they mean? What relationship holds them together? “Really, universally, relations stop nowhere,” Henry James wrote in his preface to Roderick Hudson, “and the exquisite problem of the artist is eternally but to draw, by a geometry of his own, the circle within which they shall happily appear to do so.” Bolaño once came to my office with Rodrigo Fresán when I was the editorial director at Emecé, to talk about a collection of John Cheever’s stories titled “The Geometry of Love.” He left with a full set of Borges’s Obras completas (Complete works). I found it in his library beside another full set on that first day of locomotives and tobacco.

Here’s an early clipping Bolaño carried with him all the way from Mexico. Back then, journalists still tended to misspell his name by adding an “s”: “Bolaños.” After it happened a few times, he finally decides to blotch the “s” out with ink.[2] How much is revealed in that simple gesture.

![]()

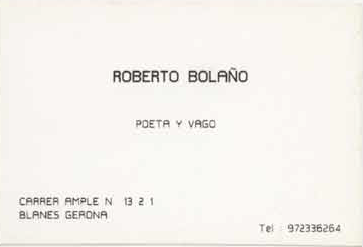

On that first visit to Blanes, López showed me several notebooks, papers, and personal objects. Octavio Paz’s work had occupied a privileged spot beside Bolaño’s writing desk. There was a keepsake he had brought all the way from Chile: a small vase decorated by his maternal grandfather using colored fragments of papier-mâché. López told me it had been one of his most prized belongings. I saw his war games, his postcard collection from which he plucked Jack Vettriano’s painting The Billy Boys for the cover of The Savage Detectives. His business card from 1988: “Poet and Sloth” it reads. The papers and objects had been stored in boxes in a small crawl space in the attic.

López had been instrumental in creating an environment for Bolaño to focus on writing. She brought economic and emotional stability, the framework of a family, grounding. They moved to Blanes together in 1986 because she landed a good job, and she encouraged him through the days when his manuscripts were being rejected by editors and agents alike. She spurred him on as he tried his luck on the local prize circuit; helped research guidelines and prepare and send the pieces out. “My children, Alexandra and Lautaro, are my only homeland,” Bolaño said in the last interview he ever gave, to Mónica Maristain.[3]

The sheer volume of notebooks, diaries, manuscripts, letters, drawings, and clippings, more than 14,600 pages, meant that organizing the archive would be no small task. The summer heat and coastal humidity of Blanes were not ideal conditions for the papers, and López decided it was time to go through it all, protect them and organize them into a researchable whole. She decided not to organize the papers chronologically or thematically, but instead to follow the order Bolaño had left them in when he died; some were in boxes, or grouped into folders, others had been on his desk (specifically, a series of folders with the materials of Woes of the True Policeman). Bolaño’s library, though, had been dismantled and moved into the new flat without respecting his original order. López later realized the mistake; he had been very meticulous, and would rearrange an entire unit of his library to accommodate a new addition precisely where it was meant to be.

![]()

At first, I worked remotely from Madrid. My first task was reading and evaluating a copy of the typescript The Third Reich. I still remember a blistering summer afternoon when I met with Javier Marías in his home library to work on a chapter of my book A Thousand Forests in One Acorn. I had been reading my typescript copy of The Third Reich in a café earlier in the morning, and had it in my satchel. I pulled it out and set it on the table beside me to shuffle around for my recording device. And then I looked up and it dawned on me . . . what are the odds? Bolaño’s war game novel (as yet unpublished) here on this table beside Marías’s collection of toy soldiers . . . I felt a little shiver, and put the manuscript back into my satchel as quietly as I could before turning on the recording device.

The second book I worked on, Woes of the True Policeman, was more complicated to edit because the materials were spread into a series of folders with an index. The novel is episodic, and Bolaño had been gathering and ordering episodes written earlier into final versions. I had to parse the latest versions of the episodes, some of which were on a hard drive and others still in typescript. Woes springs from a writing cycle that lasted several years, and in a way is to 2666 what Amulet is to The Savage Detectives. I had to do a fair amount of sleuthing, and López thanks my pseudonym in the acknowledgments.

Bolaño uses ekphrastic expression as a staple of his poetics; the idea of the “contraire”—plastic arts, sculpture, dance, film—figures in almost every one of his novels, and in Woes he focuses attention on the artist Larry Rivers. There is a great formal relationship between image and text, between the eye, point of view, how to see and not merely look, what is visible and invisible. His repeating iconography prompts a sense of extreme intuitiveness. The true, savage reader is clairvoyant, as Bolaño once said in a 2002 conversation with Rodrigo Fresán for Letras Libres: “It’s a matter of clairvoyance. I mean, on one hand it’s a lucid and exhaustive reading of the canonical tree and on the other it’s a time bomb. A testimony that explodes in the reader’s hands and projects into the future” (my translation).

![]()

Eventually, my work required spending time in the archive itself, in Blanes, sleeping over on weekends or holidays, reading through the papers one by one. I also began evaluating the three notebooks that contained The Spirit of Science Fiction, and many of the stories that are still unpublished, along with a poetry manuscript from Mexico titled “Un montón de estrellas fracasadas” (“A cluster of failed stars”).

At that time, López asked me to prepare a curated autobiography, a selection of quotes taken from these notebooks and papers. I gave it the working title Bolaño Dixit. I began searching for his comments and insights into his motivations, his influences, his methodology, his obsessions; all in his own words. But the behind-the-scenes tension surrounding Bolaño’s work had intensified: one Chilean writer even publicly claimed to have been approached by the widow to act as a ghostwriter. Others felt they knew Bolaño’s own wishes, channeled from the great beyond, as to whether or not he wanted his unpublished work to be released. Many failed to consider that Bolaño’s last novel ever published in his lifetime, Antwerp, had been written by hand in one of his diaries—“Diario de vida”—circa 1981. “The only novel that doesn’t embarrass me,” Bolaño said of it, which New Directions quoted on the back cover of their edition. Bolaño himself had begun going back to these very materials, his work written in the late 1970s and early ’80s, now that he had a stable publisher in Anagrama. His poetry collection, The Unknown University, also published posthumously, opens with a poem written in October 1990, “My Literary Career,” describing his despair over being left outside, in the publishing desert: “Rejections from Anagrama, Grijalbo, Planeta, certainly also from Alfaguara, / Mondadori. A no from Muchnik, Seix Barral, Destino . . . All / the publishers . . . All the readers / All the sales managers . . . / Under the bridge, while it rains, a golden opportunity / to take a look at myself: / like a snake in the North Pole, but writing. / Writing in the land of idiots. / Writing with my son on my knee. / Writing until night falls / with the thunder of a thousand demons. / The demons who will carry me to hell, / but writing.”[4]

The work on Bolaño Dixit is what eventually transformed into the kernel of the exhibition—Archivo Bolaño 1977–2003, Déjenlo todo nuevamente—which debuted in Barcelona in March 2013, and marked the ten-year anniversary of his death.

![]()

Some things that caught my eye during this first read through the archive: the extent of his obsession with war games, how much he liked to draw and doodle, and how broad his interest was in other forms of art: film, painting, installations, sculpture, photography. Enrique Vila-Matas, a close friend of Bolaño’s, wrote an essay for the exhibition catalog that discusses Bolaño’s “time of silence” when he was writing feverishly and in perfect anonymity. These papers bear witness to the nearly twenty years he spent as a complete outsider, writing and writing against the odds, in the faith that someday, somehow, someone, somewhere . . .

Since the papers and notebooks didn’t follow a chronological order, but were arranged according to how Bolaño had left them, the need imposed itself for some sort of instrument that could map out the dates of the unpublished stories, poems, and novels. I began to build a document ordering his work chronologically according to the date of creation, both the published and unpublished work all together. Meaning, I prioritized the date of creation over that of publication. I called it the “Cronología creativa” (creative chronology). What became clear is how Bolaño’s writing nestles into three very distinct periods, which coincide with geographical locations: Barcelona, Girona, Blanes. He was in Barcelona from 1977 to 1981, recently arrived from Mexico and teaching himself how to write his much-desired novel-poem, which we’ll discuss shortly. He lived in Girona from 1981 to 1985, a much darker time in his life, a period of isolation, of despair and penury. But it’s also when he found how to finally wrestle the material he’d been writing in Barcelona into a system of poetics. Here he began a life-saving correspondence with Enrique Lihn, and wrote his first novels. And finally, the period in Blanes, from 1986 to his death in 2003, where he settled into family life with Carolina López. This was his period of intense production, after finally breaking into trade publishing.

![]()

His early notebooks, just landed in Barcelona, are light-hearted, amusing. In 1978 they darken when he experiences heartbreak, his girlfriend leaves him, and the Jorobadito (a hunchback dwarf) appears. This was the original title for Amberes: El Jorobadito. The short pieces and poetry give a sense of how his method was taking shape; he would write a thought or see an image, capture a metaphor quickly, and then write it again a different way, in verse perhaps, add it to another poem or cut it up or turn one column into two or a poem back into prose, Queneau-style. He was reading Alain Robbe-Grillet at the time. He also wrote from visual prompts, paintings, sculptures, or photographs, even the dance of Martha Graham.

In the notebook “Literatura para enamorados 1,” we find a first mention of the Italian painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo: “Colorful capillary roots on the sky’s stomach detach and fall over us. Half-burnt notebooks in children’s hiding places. The pathetic prose of fat, sensual lips like Arcimboldo’s.” And in La Virgen de Barcelona: “I commend myself to Arcimboldo, the most disdainful of them all, Madam, I commend myself to Arcimboldo, I said, contemplating the cracks in his lips.” And in his Diario de Vida, poemas cortos II notebook (Life diary, short poems II), we find the last line of a poem dedicated to Gustave Moreau: “Feverish days in Barcelona with wrinkled clothes and cracked lips” (my translation).

![]()

His move to Girona in 1981 represents a sort of coming of age, a time when Bolaño isolated himself and found his bearings. The novel Monsieur Pain and the unpublished novels Diorama and D.F., La Paloma Tobruk were written during the early years in Girona, and he published a first novel, which he wrote with A. G. Porta, Advice from a Disciple of Morrison to a Fan of Joyce. In a typescript draft of a letter explaining his ideas on composition, he writes, “Caravaggio would call it the pretense of style. I think it’s a sense of the city, a fragmented sense of chaos, produced in parallel with the objective-subjective field” (my translation).

![]()

The Cronología creativa was the instrument that allowed me to begin mapping out the interlacing elements in his fictional world. For example, he had been correcting a printed copy of the Third Reich typescript by hand when he died. The novel was written in Girona in the early eighties, long before The Savage Detectives (1998, written in Blanes). But in 2002 or 2003, he changed the name of the protagonist to Udo Berger, and was adjusting the point of view from the first person to the third, so it would no longer be a first-person diary. But the decision was made to keep to the first person for publication, since he had only gotten partially through the manuscript, and to change the whole thing would have required too many editorial intrusions without the author’s ability to approve or disapprove them.

Udo Berger is the adult version of a child who appears in the “Mary Watson” section in the second part of The Savage Detectives. The character of Mary Watson is based on a British girl named Voirrey, whom Bolaño met in 1979 while he was a night watchman at the Estrella de Mar campground.[5] She was helping him translate some of Jack Kerouac’s cantos from Mexico City Blues for a poetry anthology Bolaño wanted to compile. In the novel, Mary narrates the road trip she took from Paris to Barcelona with a group of strangers in a van that belonged to Hans, a German traveling along the Costa Brava with his French wife Monique and their young son, Udo, to pick oranges in Valencia. By naming the protagonist Udo Berger in The Third Reich, it became the story of that boy’s return as an adult to the place where he’d spent time as narrated in The Savage Detectives. The novel holds many connections with other novels and stories, among them Distant Star, The Skating Rink, and Telephone Calls. Despite being written several years before, The Third Reich is diegetically posterior to The Savage Detectives. Wouldn’t it seem arguable that he meant for the novel to be published?

The chronology shows clearly why there is such a rich afterlife of unpublished work, and his methodology of cycle and recycle. It permitted me to locate the origin of some of Bolaño’s obsessions with certain images or metaphors, and to follow their evolution. It helped me understand which novels or stories or poetry collections he wrote in parallel with other projects, and for how long, and how they interact with each other and with what he was reading at the time, what he was seeing, the music he was listening to, all within the context of what was happening in his life and the world.[6]

![]()

Clippings, playbills, and other keepsakes are valuable materials too, since they give a sense of what sparked a writer’s curiosity or were in some way meaningful enough to be salted away. Especially in the case of Bolaño, who led an iterant life. Examples of these are movie playbills like The American Friend by Wim Wenders, which dates from 1978–1979 and coincides with the writing cycle he called “La Virgen de Barcelona.” Or a Solaris flyer from Cine Maldà, which he saw on January 18, 1979. Or Godard’s Alphaville, whose date is not specified, though Bolaño writes, “I am Lemmy Caution,” on a postcard sent to Enrique Lihn on April 8, 1983. He kept photocopies of papers teaching how to focus a film camera and the vocabulary of perspective, or an obituary written by Julio Cortázar on the death of Antonin Artaud, torn from a book and probably among the papers that Bolaño brought with him from Mexico with his marginalia and underlined sentences. There are the notes for the introduction to an anthology he was compiling that included a selection of his own translations of Kerouac’s cantos in Mexico City Blues. Or the real ending of La pista de hielo, which he may have removed as a result of reading Hemingway’s iceberg theory in Death in the Afternoon.

His notebooks tell us that Bolaño had every intention of becoming a novelist from the moment he arrived in Spain, in 1977, and clearly contradict the idea of only writing narrative in order to provide for his family. He was exploring narrative fiction as an extension of the poetic act, drawing on the techniques and spirit of poetry as applied to a longer work of prose. Bolaño often wrote to himself as he worked, and in a brown spiral notebook dated 1978 and written while hitchhiking to Portugal with a Spanish girlfriend, Lola Paniagua, we find: “I want to write a novel but it’s so hard to get started.” And again, “Less young every day, fortune for some, poverty for others: I write verse, I dream of writing a novel.” And in another notebook also dated 1978, “I want to write a novel; I no longer have the patience for a long poem. How to do it, Lord? That’s how Cavafy’s hero moaned from his rathole in Barcelona, with a book on laser rays in his left hand and Franz Leiber in the right.” (All translations mine.) One form—poetry—served as a stimulant to the other—narrative—coexisting and cross-fertilizing. We can see this hybrid approach to poem-novels early on, as early as 1976 in his correspondence with Bruno Montané, which is now housed in the National Library in Madrid. Montané was in Barcelona and Bolaño still in Mexico.

![]()

And so we enter again that hallowed space where the creative act takes place, the hovering presence of a medium bringing something into being through a physical act, pen to paper. Here we follow the recurring patterns as they transubstantiate, and draw themselves out of the mystery of consciousness and into the being of fixed language, sentences setting like fingers of frost on a winter window. Look, here emerges that motif, image, metaphor for the first time, see how he plays with it again over here, see how it mutates in this novel, in that story.

What caught my attention was a sentence repeated randomly in his notebooks, here and there: “I’m immensely happy!” He wrote it to himself almost like a hiccup, caught in the very the act of feeling, of bliss. What a paradox, I thought. Reading through other expressions of despair, loneliness, indigence, suddenly I realized that this writer who lived “exposed to the elements and undocumented like others live in a castle,” both in Mexico and Spain, a “trapeze artist without a trapeze,” whose explorations of violence and evil probe the darkest recesses of the human psyche, experienced plenitude, immense joy when he was writing. He suffered in life, but not while writing. It was his survival mechanism; a state of blessedness, of grace, and inviolability.

María José Rucio, director of the manuscripts and incunabula section of Spain’s National Library, said upon the acquisition of some of Bolaño’s letters: “What an author writes in that private moment, the choice of paper, how the text is arranged, the color of the ink, a note in the margin, presents us with the writer divested of artifice, it’s the true image stripped bare of the person, instead of the legend.” One can follow how Bolaño’s handwriting gets smaller and tighter as he gets older, it becomes impeccable.

![]()

People have asked if reading through someone’s private papers when they are no longer with us isn’t in some way a violation of their privacy. I believe that this “immensely happy” writer, the Bolaño alone in his studio at night wrestling language, monsters, and imagination, expected someone to read his papers, someone from a future into which he projected his writing so often. Bolaño used the topos of the found book or notebooks full of clues throughout his work: García Madero finds Cesarea Tinajero’s notebooks in The Savage Detectives; Hans Reiter finds Ansky’s half-burnt notebooks hidden in the fireplace in 2666 (and here we go back to his metaphor written all the way back in Barcelona of half-burnt notebooks in children’s hiding places to see how long a metaphor takes to make its way to the surface); and there’s Pedro Huachofeo’s book, The Paradoxical History of Latin America, in The Spirit of Science Fiction: “The coded messages are in abundance, you’ll see [. . .] I’m telling you all this because the soul of the dead author [is] present in this book [. . .] along with other ghosts.” Or the book of geometry that mysteriously appears in Amalfitano’s suitcase in 2666, hung on a clothesline and made to survive the elements.

![]()

One evening in Blanes when I sat down to read at my desk in the archive, I checked to see if the pigeon was still hiding in a doorway in the alley below. I had passed it earlier in the day when I arrived, and figured it was likely sick and looking for somewhere to convalesce. Or die. I pulled an archive folder from the shelf and slipped the notebook and some papers out of their plastic sheaths. I started reading a clean handwritten draft of D.F., La Paloma Tobruk, one of Bolaño’s incomplete early novels. I read exactly this (my translation):

She opens a drawer of the book case. It’s full of manuscripts. She picks one up at random: “At times I’m immensely happy!” The handwriting is small. She takes a sip of beer and continues reading other notes (it’s beside the point to bring this up right now, but she doesn’t feel she’s violating something by reading through these sorts of notes, diarios de vida, or whatever). What matters, I mean what really matters, is that the beer is getting warm, and the moon is visible above the little alleyway for a few seconds . . .

![]()

“What is the difference between a sentence and a sewn. What is the difference between a sentence and a picture. [. . .] A sentence is drawers and drawers full of drawings.”

![]()

Bolaño was interested in the work of a relatively obscure French philosopher named Jean-Marie Guyau. Friedrich Nietzsche was inspired by his writing and also Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin, who considered him an “Anarchist without his knowing it.” Guyau’s gravestone reads: “Ce qui a vraiment vécu un fois revivira” (He who truly lived once, will live again).

An earlier iteration of the German Benno von Archimboldi in 2666 was the French J. M. G Arcimboldi, who figures in The Savage Detectives. They are both authors of a novel with a perfectly Borgesian title, The Endless Rose. And I think of the Second Infrarealist Manifesto, “Fractures of Reality,”[7] written by Bolaño in Barcelona in 1977, worried about his Infra poets and colleagues left in Mexico to contend with the ever-hostile establishment. He signed “in Barcelona, Rose of Fire,” the city’s nickname on the international anarchist circuit. In By Night in Chile we read: “He returned with the Italian countess or the duchess or the princess through the series of salons opening one on to another like the mystical rose that opens its petals to reveal a mystical rose that opens its petals to reveal another mystical rose and so on until the end of time, speaking in Dante’s Italian . . .”[8]

His handwritten notebooks demonstrate perfectionism and attention to detail, debunking the suggestions that his magnetic prose is the result of freestyle or automatic writing. Though he did use those techniques to gather material, a deep dive into his subconscious fishing for natural symbols. But once these symbols emerged, he worked and reworked and polished and ordered. The sheer readability of his narrative style may feel like happy improvisation, but he was persnickety and sculpted his structures with painstaking care. Even his correspondence was first written by hand and perfected before writing or typing the final letter or postcard to be sent. As the saying goes, improvisation is hard work disguised as fun.

Bolaño saved certain texts or poems or prose pieces for years, polishing and correcting to the point where metaphors would be partially erased yet remain like palimpsests, ghostly presences lying below the text, a lingering sotobosque or forest of symbols that look out at the reader “with familiar eyes”; correspondences reframed, turned inside out, upside down, reverse and obverse. Eyes, statues, windows, bones, knives, lips, the wind in the trees, the number three.

The more familiar one is with Bolaño’s writing, the more you begin to notice these codified presences, these patterns, this iconographic alphabet in the style of Joan Miró, and a sense of complicity with the author coalesces into an experience of life in the poetic mode. “I’m condemned, fortunately, to having a small but faithful readership,” Bolaño says in Andrés Braithwaite’s compilation Bolaño por sí mismo: entrevistas escogidas. “They’re readers who want to enter this metaliterary game and the game that is my entire body of work. It’s fine for someone to read one of my books, but to understand it you have to read them all, because they all refer to each other” (my translation).

Back in Barcelona now, I continue to ponder Howe’s telepathy, Borges’s sphere, Calvino’s locomotive, and Bolaño’s tobacco, and intone the notion that of all the mysteries of life, none is deeper than observing the act of creation at the surface of the visible. ![]()

NOTES

[1] “What is this called? I asked. Ocean. A long and slow university.”—VM. See https://www.cccb.org/es/multimedia/videos/reportaje-exposicion-archivo-bolano-1977-2003/238105.

[2] Orlando Guillen, El Nacional, “El Amor También es Clandestino,” n.d., clipping from the folder “Correspondencia Infra,” AHRB, Archivador 14.

[3] From the Playboy interview with Mónica Maristain in Between Parentheses (New Directions, 2011; Entre paréntesis, Anagrama, 2006).

[4] Bolaño, The Unknown University, trans. Laura Healy (New Directions, 2013), vii.

[5] See the Soledad Bianchi archive of letters: “Acerca de mi (Sagrada) familia,” Documento RB-D021, written in November 1979, http://culturadigital.udp.cl/index.php/documento/acerca-de-mi-sagrada-familia/. There are also a few unpublished poems, such as “Voirrey’s Story,” Documento RB-D016.

[6] Here I use only the version that was given a graphic component for the catalog of the Archivo Bolaño 1977–2003 exhibition at the CCCB, which organized the structure of the exhibition and opened the show, see Catálogo Archivo Bolaño (CCCB, 2013), 29.

[7] Published in Granta en español 13, which is dedicated to Mexico.

[8] Bolaño, By Night in Chile, trans. Chris Andrews (New Directions, 2003), 28.

Valerie Miles, an editor, writer, and translator, cofounded Granta en español in 2003. She established the NYRB Classics series in Spanish, curated the exhibition dedicated to Roberto Bolaño’s archival papers, and edited Bolaño’s posthumous work. She teaches translation and creative writing at Pompeu Fabra University, has written for the New York Times, the New Yorker, El País, and the Paris Review, and is the author of A Thousand Forests in One Acorn. She lives in Barcelona, Spain.

Illustration: Barry Gifford