As soon as he saw his friends Anselmo Bris and Martica Ojos Bellos at his door, Mario Conde confirmed, once again, that his instincts were as inscrutable as they were infallible: this would not be an ordinary day.

He’d suspected it from the moment he woke up and saw the trees in the garden petrified by the heat, too blistering even for the imperturbable sparrows. Although it was still only April, a sticky, sweltering day surely lay ahead, one in which, at the very least, nothing good would happen. Did he dare to brave the streets, scouting for people desperate enough to sell their old books or anything else? He couldn’t shake the feeling that something strange was in store for him, and this intuition manifested, as always, as a throbbing pain on the left side of his chest, a burning sensation that was worrying but, up to now, had not yet managed to kill him. So before drinking his coffee and slipping into his pants, stiff with accumulated sweat, he ripped last year’s calendar off his bedroom wall. It had been hanging across from his bed for several months, still showing the month of October, as a way to torture himself with the numerical proof that the ninth of that month—circled several times—had come and gone, meaning he’d arrived at the advanced age of sixty and was now officially a shitty old man with few years left to live.

His finances were in such a sad state that he needed to go out and scrounge up some cash, as he’d done every day since leaving the police force, all those years ago. But considering the unseasonably warm weather, combined with his weighty premonition, Mario Conde decided it would be best to stay at home. He could practice one of his regular pastimes: sitting around lamenting his miserable life, the disastrous social-civil-economic situation of his neighborhood, his city, his country, his continent, and the world as a whole. Or, if he could muster the energy, he could sit at his typewriter and knock out another page (or more, with luck) of the sordid, disquieting tale of a man very similar to himself with a few (likable) friends and many fellow countrymen (many of them assholes) very similar to the people he knew.

But then the knock at the door pulled him out of his thoughts, and one look at Anselmo and Martica, his old high school classmates, widely considered to be an enduring and indestructible couple, confirmed his intuition.

“Did we wake you?” Anselmo asked, shaking Conde’s hand.

Martica, meanwhile, leaned in to plant a kiss on his cheek. “You need to shave,” she said. Her face showed her age, the same age as Conde, but her eyes, always so beautiful and expressive, were clouded with worry and sadness.

Conde’s detective instincts, still alive and well, had kicked in, so he neither responded nor objected to her comment. “What’s wrong?” were his words.

In the kitchen over cups of coffee, Conde learned the reason for his former classmates’ unexpected visit: Juan Miguel.

Juan Miguel was the couple’s only child and had been like a nephew to Conde, Carlos, Conejo, and Candito. Juanmi, as they called him, was beloved by all of Anselmo and Martica’s friends thanks to his natural charm: he was kind, clever, mischievous, cheeky without being spoiled or annoying, able to talk to his parents’ friends almost as an equal in the frequent gatherings around food and drinks during the period of relative bonanza they’d enjoyed. More than a child, he was an accomplice. Juanmi was intelligent, exuberant, and, on top of everything else, a beautiful boy: thin, with corkscrew curls and his mother’s eyes set in the face of an angel. He was constantly playing diabolical pranks that never altered the saintly expression on his face. His parents and adopted uncles predicted a bright future in which Juanmi would rule the world.

But things changed when Juanmi went out on his own. It was the 1990s, a time of devastating crisis, when everything was scarce and people had to fight for survival as the youth of Juanmi’s generation began to leave the country. In the boy’s case it manifested as a kind of bipolarity: He married his girlfriend and, swapping things from his grandparents’ family home, managed to set up a small apartment for himself in the La Víbora neighborhood. But at the same time, he abandoned his studies, believing that a university degree would do nothing to improve his life. That’s when he descended into the world of shady yet highly profitable business dealings, converted to Afro-Cuban Santeria, and became a babalawo priest. But his newfound faith didn’t fool anyone who knew him: Juanmi was pragmatic and had discovered mysticism as a way to collect money from unsuspecting believers seeking help from the beyond. He was called “godfather” by many Mexican and Spanish tourists who had fallen into his trap, bringing him gifts whenever they visited the island.

Everything was going fine until Juan Miguel’s parallel lives began to converge and his loved ones seemed to resent it. Conde had heard that Lulú, Juan Miguel’s girlfriend of many years and now wife, disliked the young man’s lifestyle and that the marriage was in trouble. The breaking point came when Lulú, sent to Canada on a professional development course for her job as a geologist, left the university that was hosting her and crossed the border into the United States, seeking asylum. The news came as a heavy blow to Juanmi, who’d been unaware of his wife’s intentions. The happy-go-lucky huckster became focused on a single objective: finding his wife . . . But, as one of the most famous lines of Cuban poetry rightfully reminds us, we have “the cursed circumstance of water everywhere.”

![]()

Anselmo and Martica had last seen Juanmi a week ago and he’d phoned them five days prior.

“He called to tell me that he loved us very much and to say he was sorry,” Martica told Conde. “And when I asked why, he said I’d find out . . . That left me very worried, and that same night, almost by chance, I discovered that the jewelry box in my dresser was missing my grandmother’s engagement ring, Anselmo’s father’s gold chain, and a Patek Philippe watch that my dad found ages ago on the floor of the Payret Theater.”

“When things were at their worst,” Anselmo added, “we almost sold it all but ultimately decided not to. It was like selling off our family . . .”

“I remember,” Conde nodded. “How much did they offer you at the time?”

“Five thousand dollars,” Anselmo said, “but we knew we could’ve gotten more. Seven, eight thousand . . . Who knows . . .”

“He knows what that jewelry means to us! If he stole it, he plans to use the money to leave Cuba,” Martica declared. “And we’re sure that’s it because the day after he called us we went to his house and it was almost completely empty.”

“And you haven’t heard from him again?”

Anselmo and Martica shook their heads in unison, as if running on the same battery.

“And we’re scared to go to the police to see if they know anything,” Anselmo added. “He might still be in Cuba and it could cause trouble for him . . . But if he left by boat he should’ve sent some sign of life by now. We called Lulú again this morning and she claimed she hadn’t had any news from him either. But I thought she sounded very odd, like she was nervous . . .”

Martica let out a sob, and, mustering all his tenderness, Conde placed a hand on her shoulder: the woman feared the worst. Attempts to flee the island across the Straits of Florida all too often ended in tragedy, and traveling through Mexico to cross the US border was risky as well.

“And now you want . . . ?” Conde began.

“We want to know what happened,” Anselmo said, completing the thought. “And you know how to find someone, Conde.”

Mario Conde nodded. All he could do was nod, remembering Juanmi, who, at age four and thanks to him, was able to recite a string of thirty-two curse words without repeating a single one.

Juanmi’s spiritual godfather was one of the most well-known babalawos in the country. In addition to being a priest of the Yoruba rituals, he was a member of the secret Abakuá sect and an active Freemason. And Conde knew that no one initiated in the prophetic art of Ifá’s divination tray, not even Juanmi, would dare to take an important step without consulting that deity, who could see the future and predict destiny.

Lorenzo Antúnez was a mixed-race man with a solid build and a changeable personality: he could be loquacious when he wanted to be, or as closed as a padlock that had lost its key when he didn’t. He’d risen to prestige thanks to the seriousness with which he practiced his beliefs and his deep knowledge of the stories, rites, and functions of the religion.

Antúnez received Conde in his living room. If not friends, they were at least cordial acquaintances; Conde had visited on more than one occasion, offering books he thought might be of interest. Seeing that Antúnez was a true man of faith and not some scam artist trying to take advantage of people, Conde had always given the priest a more than reasonable price.

“Yes, Juan Miguel came to see me,” Antúnez said when the bookseller explained the reason for his visit.

“Do you remember when that was, Babalawo?” Although the man was only a few years older than Conde, he always addressed the priest in the most polite terms: something in Antúnez’s bearing seemed to command respect.

“He came to see me often after his wife stayed in the United States . . . He was very upset and needed to talk . . . Then he didn’t come around for a while, but he turned up about ten days ago asking for a spiritual consultation.”

“And did you consult for him, Babalawo?”

“Of course . . . Juan Miguel is a madman, but he’s one of my godsons.”

“And could you tell me what Ifá said?”

Antúnez smiled, his gold tooth lighting up the small room decorated with African and Catholic religious symbols, along with diplomas for merits within the Freemasonry system.

“That is personal and—”

“Antúnez, you know who I am and what Juan Miguel means to me. He might have gotten himself into some sticky situation . . . or the worst could’ve happened. He’s out looking for money and . . .”

The man nodded, his gaze fixed somewhere above Conde’s head, weighing esoteric loyalties against earthly necessities. Finally, a sense of responsibility to his disciple seemed to win out. “Ifá told him that it’s not always a good idea to go chasing after a skirt . . .” he began.

“His wife,” Conde translated and the babalawo nodded.

“He also reminded him that the sea is beautiful, but that its beauty hides a treacherous nature.”

“Because he asked about leaving by sea?”

“Yes . . . but Ifá also told him that man is even more treacherous than the sea . . .”

Conde nodded. “And did Juan Miguel tell you, Babalawo, what he was planning to do after hearing Ifá’s warnings?”

The priest nodded. “He said that even though things had been rough for a while, he couldn’t live without his wife . . . Some men are like that, my friend.”

![]()

Conde ordered a double rum at the Bar de los Desperados and went to sip the infamous spirit in the shade of an almond tree on a low wall far from the other drinkers. He needed to decide which of the two paths that had opened before him would lead more directly to a clue about Juan Miguel’s whereabouts. He could either follow the trail of the jewelry, or delve down into the darker world of migrant smuggling. But what if the jewelry, along with the money from the sale of his belongings, was a direct payment for a spot on a boat destined for Mexico or Florida? Conde knew that the trip cost about ten thousand dollars and that, with the jewelry he’d taken from his parents, Juanmi could’ve easily obtained that amount, possibly more.

As he smoked and drank, the fiery liquid intensifying the dogged midday heat, Conde thought about all the factors that shape a person’s destiny. Juan Miguel, with his supportive family and innate intelligence, should’ve had a good life. Anyone, even Ifá, perhaps, would’ve predicted that he’d complete his engineering degree and begin to earn an honest living. But the country’s painful economic collapse marked a different course for Juanmi, and the young man chose a more lucrative life in the margins over near starvation as a respectable engineer, like his father, trapped in a career that provided barely enough to survive. Only his love for Lulú had spared him a more drastic descent. But Lulú had been unwilling to accept his incursion into the world of dishonest dealings. And now, it seemed, Juanmi had gone in search of that lost love. His many years’ experience with criminality could perhaps spell his salvation: Juanmi had learned to swim in rough, dangerous waters where large sums of money changed hands, where loyalty and honor were nonexistent.

Conde, ill-informed and disconnected from the depths of the Havanan underworld, felt incapable of finding his way to any of the doors Juan Miguel might’ve knocked on or even walked through. His best option, as always, was Yoyi Palomo, his partner in the secondhand book trade, skilled at swapping whatever was necessary to go on living, drinking, even eating.

Yoyi was only a few years older than Juanmi, and, in every sense, a perfect example of that pragmatic younger generation. When Conde explained the search he wanted to undertake, and why, Yoyi immediately halted his commercial activities and placed himself at his friend and colleague’s disposal.

“We should start with the jewelry,” said Yoyi as they approached his powerful, elegant 1957 Chevrolet Bel Air. “A Patek Philippe from the fifties has a very specific set of buyers in Cuba. And I know all of them . . .”

The first stop Conde and Yoyi made was at the home of Tata La Manta, a watch dealer. All the most exquisite examples of Swiss watchmaking had passed through his seasoned hands. The old mansion in El Cerro where La Manta lived, restored from top to bottom, looked to Conde like a monument to the bad taste of the new rich born from crisis and poverty: walls hung with tapestries depicting pastoral scenes, polished tile floors, furniture upholstered in gleaming vinyl, a bar with baroque aspirations in one corner of the main room built from ornately carved wood.

After Yoyi introduced Conde as his business associate and someone who could be fully trusted, the exchange between the younger man and La Manta was quick and tense, reminding Conde of scenes from a nature documentary in which a tiger and a lion fight over a gazelle: both were fierce businessmen and Conde accepted his role as a fly on the wall.

“A Patek Philippe from the forties or fifties, with a crocodile-skin band, possibly original,” said Yoyi, kicking things off.

“I haven’t seen a Patek in a couple months. The well seems to have dried up. That’ll happen if you take and take and never replenish the supply . . .”

“If it wasn’t you, who could’ve bought it?”

“Who knows,” La Manta said and shrugged his shoulders. “Millán the Madman or Ramón, from La Lisa maybe . . . Just about anyone would buy a Patek Philippe. The trick is to find a good buyer . . . but that depends on how eager you are to get rid of it. Was it stolen?”

“Yes and no.”

“How does that work?”

“Someone stole it from their parents, but the parents haven’t reported anything.”

“And what did he want it for? Drugs? Gambling debts? Cash? To get out?”

“It seems like it was to get out. By boat. Direct to Miami, preferably,” Yoyi added.

“That’s not my scene. I deal with diplomats, businesspeople here in Cuba, or regular buyers who fly in every few months to pick things up.”

“But you know everything that happens in Havana, down to which dogs have ticks,” Yoyi said. “This isn’t a business deal, Tata. It’s . . . a family matter.”

Tata La Manta’s reddish eyes stood out from his dark face. His many years of successful business dealings had sharpened his ancestral instincts, acquired over generations of survival through hardships and horrors, hunger and persecution. “Gabriel Quintana,” he said, looking to Conde. “Gabito. I don’t know where he lives but he runs his business in La Güinera. He’s a dangerous guy. And I know a dangerous guy when I see one.”

![]()

La Güinera slum had sprung up many years prior and had seen little improvement since then despite concerted efforts to combat the evils of poverty and marginality. Conde remembered that in his childhood, mentioning La Güinera was like mentioning hell: a place no one would willingly enter.

Conde trotted out his most convincing arguments and persuaded Yoyi to stay behind as he descended into the depths of the city. He still knew how to look out for himself, and, going alone, he’d have better chances of an encounter with Gabito. Yoyi grudgingly agreed, on the condition that he would remain on hand as backup, parking his Bel Air at the top of the road leading down into the slum.

Conde walked the shantytown’s main artery, surprised at the number of people of all ages, races, and appearances crowding the streets or gathering on the corners to buy, sell, or offer whatever service they could in exchange for a quick buck. Did anyone here have a steady job? Their opportunities for earning an honest living, thought Conde, couldn’t be very promising.

Conde stopped several people to ask if they knew Gabito and where he lived, but everyone said that they’d never heard of such a person and so obviously had no idea where to find him. So Conde took out a cigarette and sat on a boulder in the shade of an old laurel tree to wait for Gabito. The message had surely been relayed.

Twenty minutes later he saw three men approaching. One was mixed race, one was Black, and the other White. Several paces from Conde, who remained seated, the White man stepped forward and asked: “Why are you looking for me?”

Gabito was a tall, corpulent man in his thirties. If a face can reflect a person’s character, his was an open book: the dark scar across his chin and the fierce intensity in his eyes showed his violent relationship to humanity.

“I was hoping you could shed some light on something,” Conde responded, still sitting, drawing lines in the dust with a stick.

“I’m no lighthouse. Who are you?”

“I’m Juan Miguel’s uncle. I’m trying to find out where he is. And I think you might know.”

Gabito smiled. Conde was surprised by the gleaming perfection of his teeth.

“I don’t know any Juan Miguel . . . Or do you mean Juan Gabriel, the singer?”

Now it was Conde’s turn to smile and shake his head as he finally stood. He threw a glance at Gabito’s acolytes, tense as coiled springs.

“Gabito . . . I was once a police officer, years ago, now I’m a nobody . . . just a shitty old man. But I don’t like to be reminded of it. I don’t care about whatever business you’re involved in, although I could make things difficult for you if I wanted to because I still know plenty of officers who could write a doctoral thesis on you.”

“Are you threatening me?”

“No, because I know that you and those two bulldogs behind you could get rid of me in under a minute and no one would have seen a thing. I’m simply explaining that I have no intention of butting into your business, even if I don’t like it very much. I just want to know what happened to Juan Miguel. It’s a family matter,” said Conde, and, seeing that Gabito looked away, pensive, he decided to press further. “Lorenzo Antúnez is looking for him too. Juan Miguel visited his godfather a few days ago and he received a bad omen: Ifá told him to watch out for the sea and I know what Juanmi was thinking . . . Aren’t you one of Antúnez’s godsons too?”

Gabito looked away again. Conde knew that he was dealing with an intelligent man, more intelligent than most of the people around him, who owed his success to his cleverness. But intelligence doesn’t always come with sensitivity. The man was making calculations, weighing odds, taking stock, and Mario Conde could only hope he’d pressed the right button.

“No, Antúnez isn’t my godfather . . . Juan Miguel is my godfather.”

The afternoon sun hung over the calm sea, bathing it in a blinding patina of gold. Conde and Yoyi stood in an empty bend of the coastline, several miles beyond the Santa Fe beach. They were beginning to think that Gabito had wasted their time when the outline of a man appeared against the setting sun, dodging reefs and rocks. As his image came into view, Conde sighed with relief.

“It’s him.”

“I’ll wait in the car,” said Yoyi Palomo, placing a hand on Conde’s shoulder before moving away along the shore. His part of the mission was now complete and what was left was a family matter.

![]()

It had been many months since Conde had seen Juanmi, who looked thinner through his long-sleeved shirt but also more mature, maybe because the young man now wore a thick black beard that somehow managed to highlight the beautiful eyes he’d inherited from his mother.

“How many curse words are there?” Conde shouted as soon as he thought Juanmi was close enough to hear him.

The young man’s mustache twitched into a smile. “Thirty-two, officially. Would you like me to recite them?”

Conde took a few steps toward Juan Miguel and hugged him. The young man smelled bad.

“How are you, Juanmi?” he asked, without releasing him.

“Good, Conde . . . And how are my parents?”

“Worried . . . That’s why I’m here.”

Juan Miguel nodded. “Do you have a cigarette?” he asked. Conde handed his pack to the young man, who took one and lit it. Conde did the same, taking a long drag. “Can we sit?”

Even under that intense sun, it was cooler on the beach than in the city center. And Conde loved the smell of the sea. He’d once dreamed of having a house, small and modest but right on the water. That dream had faded many years ago but he still loved the salty scent of the ocean.

“What are you going to do, Juanmi?”

“I’m leaving. Someone’s coming to get me . . . Tonight.”

Conde shook his head. “Why didn’t you tell your parents?”

“I couldn’t talk about it with anyone. Much less them.”

“And what if they turned you in for stealing the jewelry? Or reported you missing?”

Juan Miguel smiled and threw his cigarette toward the sea but the wind lobbed it back onto the rocks at Conde’s feet.

“The police aren’t going to bother looking for me . . . And if they did, they wouldn’t find me. You know good and well, Conde: unless you’re a politician or a murderer, no one will find you here.”

“I found you . . .”

“You’re different. You can track me down by smell.”

“That’s true . . . but it was easy. You smell terrible.”

“I haven’t been able to bathe for four days.” Juanmi smiled again. Then he stretched out a leg and put a hand in his pocket. He opened his fist to show Conde the engagement ring crowned with little diamonds and the gold chain: the inheritance from his grandparents.

“Give these back to my mom and dad. I didn’t need to sell them,” he said, handing the jewelry to Conde.

“What about the watch?”

“I’m keeping the Patek Philippe. Remind my mom that my grandfather gave it to me when I started at the university. And I want to have it with me,” the young man said, pushing back the left sleeve of his shirt to show Conde the small watch, glimmering in the fading sun.

“And you’re not going to say goodbye to Anselmo and Martica?” Conde asked as he put the jewelry away.

“No. I can’t . . . I can’t look back, Conde. You understand, don’t you?”

Conde gazed out at the sea and nodded. “And where did you get the money to get out?”

Juan Miguel turned serious. “I’m not going to tell you that. Not because you used to be a cop, but because you’ve always been such a puritan . . . And I don’t want you to think badly of me.”

Conde nodded. “I couldn’t think badly of you, Juanmi.”

“And you’re not going to the police to report an illegal transport tonight?”

“I should. Migrant smuggling is illegal and—”

“And what if it’s my wife coming to get me because she realized we’re still in love in spite of everything?”

Conde looked at the young man. Then to the sun, slowly sinking into the sea and the horizon.

“I didn’t need the money because Lulú paid for everything. But I wanted the jewelry and some money because you never know how these things are going to turn out, or when they’ll happen.”

Conde nodded and took out another cigarette. He lit it and handed the pack to his nephew.

“No, I don’t smoke . . . That cigarette I bummed from you was my last. I wanted to smoke it with you because, if you recall, you’re the one who gave me the first one I ever smoked.”

Conde stared at the burning tip of his cigarette. “No, I didn’t remember that.”

The two men fell silent. The last rays of day were fading into an evening that would soon be night.

“I have to go,” said Juan Miguel, but he didn’t stand up.

“And what about the advice the saints gave you? About the skirts and the treachery of the sea?” Conde wanted to know.

“Those saints spent their lives taking crazy risks. Why wouldn’t I take my own? . . . Have you ever fallen in love, Conde?”

Conde smiled. “A thousand times, you know that . . .”

“Well, I’ve only fallen in love once. Almost twenty years ago. With the woman who’s coming to pick me up today.”

Then he stood up and it seemed to Conde that the boy had grown taller. The former policeman stood as well, with the slight difficulty that came with age.

“Any message for your parents?” Conde asked.

“Yes . . . that I love them. But that I love—”

“Don’t say it, don’t say it,” Conde interrupted. He took Juan Miguel by the forearm and pulled him into a hug. He definitely smelled bad. But he felt sturdy, like a man. “Have a safe journey . . . and take care of that watch. I hope you’ll be happy. That’s what matters.”

“Thank you, Conde,” said Juan Miguel and he hugged him.

“Can I tell your parents that I saw you?”

“Of course, tell them . . . but give me a few days. If everything turns out all right I’ll be able to speak to them first.”

“Okay . . . Well, go on, you don’t want to miss the boat,” Conde said and he clapped the boy on the shoulder. He began walking to where Yoyi stood waiting for him, but after a few paces he stopped and turned around. “Juanmi, what was curse word number thirty-two?” he shouted.

“Resipinga,” said the other man, without stopping.

“Where did you get that one?”

“You made it up, Conde!”

Conde smiled and waved goodbye to the silhouette disappearing into the growing darkness. And then he couldn’t hold it in any longer: tears fell from his eyes. How the hell could he not cry when the whole situation was so damn resipinga! ![]()

Leonardo Padura (Havana, 1955) is a novelist and screenwriter. He has authored fourteen novels, several of which feature detective Mario Conde as the main character. His books have been translated into thirty languages. He has been awarded, among many other prizes, the Cuban National Prize for Literature (2012) and the Princess of Asturias Prize for Literature (2015).

Frances Riddle has translated many Spanish-language authors, including Isabel Allende, Claudia Piñeiro, Leila Guerriero, and Sara Gallardo. Her translation of Claudia Piñeiro’s Elena Knows was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize and the Queen Sofía Translation Prize in 2022, and her translation of Theatre of War by Andrea Jeftanovic was granted an English PEN Award in 2020. Originally from Houston, Texas, she lives in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

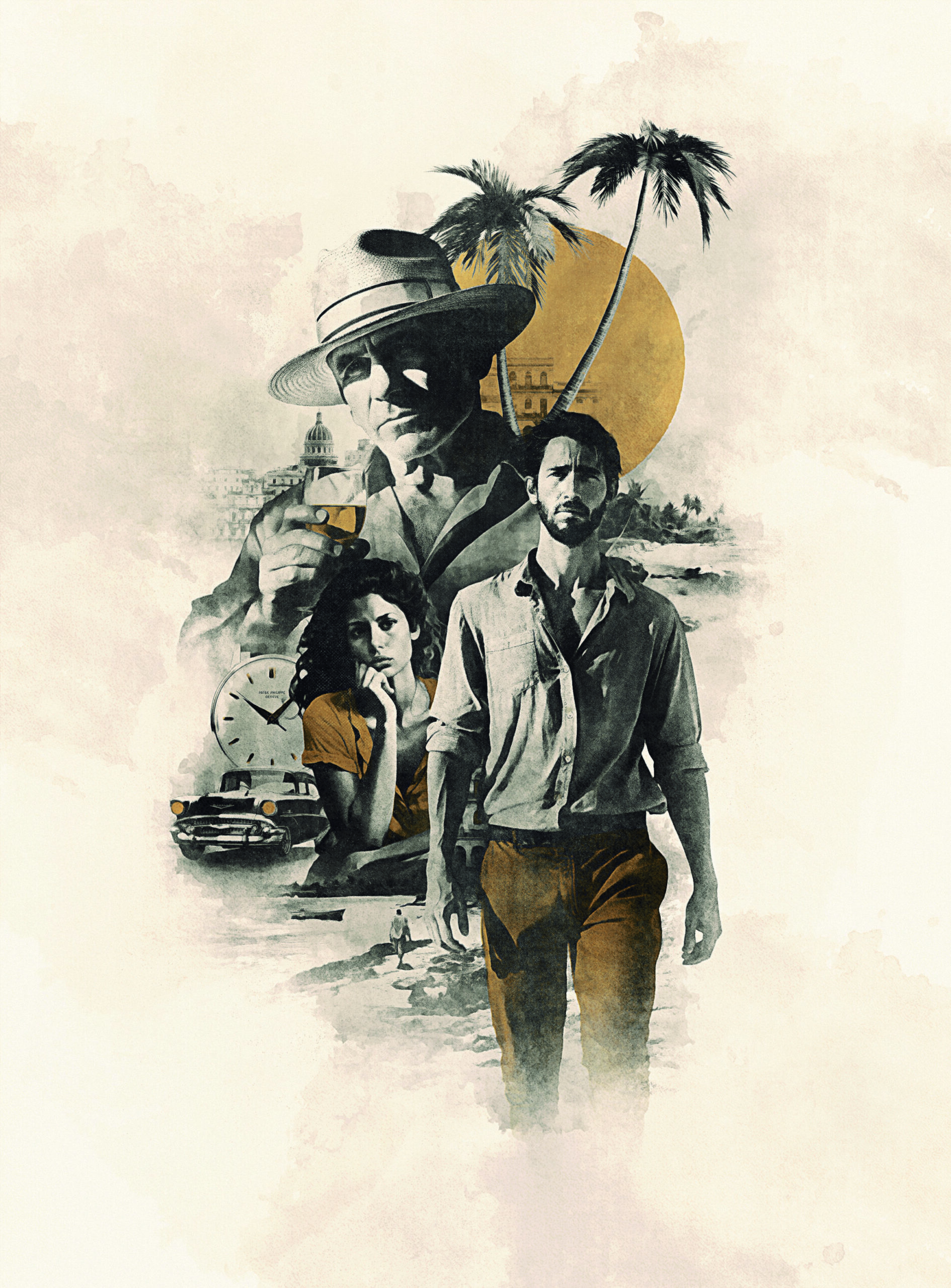

Illustration: Olivier Courbet