When I was a senior in high school, my biology teacher murdered his entire family and got away with it. I’m going to lie to you about it now, but first I need you to understand this much: he did it. He killed them all, and in the end they let him go.

I’ve been trying to tell this story ever since. Trying to find the right lies I need to tell the truth.

See me back then, on that Monday morning near the start of 1995. How I sat in my car in a strip mall parking lot down the street from my high school, waiting for the bell to ring. My hair long on the top, shaved on the sides. Four earrings in my left ear and three in my right. Wearing flannel and Doc Martens. Tapes scattered on the floor, band names like Ween and the Butthole Surfers and Nine Inch Nails and My Life with the Thrill Kill Kult and the Dead Milkmen and the Flaming Lips and Suicidal Tendencies and Ministry and Black Flag. Under the driver’s seat hid a sawed-off shotgun that I carried in my car that whole crazy savage year. We’ll talk about the shotgun later.

See the dirty cotton sky. An Ozarks winter storm clicked sleet against the windows. I sat in the cold, ate a sausage biscuit from the McDonalds drive-in, watched my classmates heading to class across the street. The school parking lot full of old beaters and a few rich-kid Mustangs and SUVs. Neil Young was on the tape deck, telling me that I was like a hurricane. I did not think I was like a hurricane. I thought I was like an iceberg floating deep in a black ocean, with just the tip breaking the water. Like a lot of teenage thoughts, this one was overwrought and dramatic and also true.

The last of the students filed into the school. I turned down the music so I could hear the tardy bell ring. I turned the music back up. This dread at the heart of me—not some premonition, nothing like that, just the deep dread that high school plants in you, especially if you have ever been one of the picked-last, the weirdos. The fear that this is all life is or can be, that all the doors marked EXIT only open onto brick walls.

My parents and my teachers always told me I wasn’t living up to my potential. My biggest fear was that maybe I was.

I fished out the second sausage biscuit. I chewed without tasting and looked out blindly into the ice.

That is how I missed the announcement of the murders.

Before the novels or the TV shows, before even my early-twenties stint as a music journalist, the first thing I ever got paid to write was in my hometown newspaper. The year before the murders, I’d written a column for the school paper about why I hated my hometown. The opinion-section editor of the local paper called my journalism teacher, Mrs. Ray, and offered to pay me to print the article on their opinion page. I had written about the blandness, the whiteness. The protests outside the movie theater when they showed The Last Temptation of Christ. The people angry over teaching evolution in the schools, who called the whole idea from goo to you, via the zoo.

I talked about the boring surface. I didn’t talk about the things that boiled underneath. I didn’t talk about the Nazi skinheads who lurked in the city square, or the people sizzling their insides with meth like they were cauterizing some wound inside them. I didn’t talk about the way the town gnawed on anything different, tried to chew it off you.

I wrote that even though it was bland it was my home, and that even though I’d leave as soon as I could, I’d come back someday.

That last part was bullshit. All I ever wanted to do was leave.

The school was cave-warm against the winter storm when I came inside an hour later. Kids clotted the hall. The bell had rung; they should have been rushing to their next class. But they didn’t. Every eye wide open. The babble of their voices had a strange new note to it. Gooseflesh bloomed on my arms, the way they say it does just before a lightning strike. I heard the words all dead. I heard the words just a baby.

Something is happening. Something is wrong.

I passed Amy C. standing in the center of a ring of girls, weeping so that her friends had to hold her up. Her legs buckled, this great hand of grief pressing down on her.

A freshman in her cheerleader uniform came moving through the halls like a deer running from wildfire. I kept moving down the hall, faster now. My blood like shook soda in my veins.

Something is happening. Something is wrong.

I headed toward the journalism classroom at the T intersection at the center of the school, passing by the principal’s office. Mrs. Davis stood with a man in a yellow sports coat, a ruff of fat above his collar. I had seen him before, talking on the news when that banker murdered his wife and got away with it the year before.

I walked into journalism class, the desks askew as always, the yearbook girls and the newspaper kids all clumped together, Mrs. Ray at the center of it, everyone whispering. And they all looked at me at once, and I guess they could see by my face that I didn’t know, and the circle opened to let me in, and I kept my face from smiling as I joined it, as they told me what the principal had said. My hands tingled, my skin slid against my flesh, like sitting by the fire at the end of a cold day.

Something is happening, something is wrong.

Finally.

Every school has a Mr. Simmons—I mean, the way we all thought of him before the killings. An animal perfectly suited to his environment of the science classroom. He was a teacher you liked, who talked to the kids like they were people. He was goofy looking. He was funny. He wore his weirdness comfortably. To us, all the teachers were weird, but most of them didn’t know it. He knew it. He wasn’t a poser, he wasn’t pretending he was something he wasn’t. That’s what we thought about him.

That’s how good he was.

Later on, after the charges were filed, my mom heard a story from one of her friends who taught English at a different school, a story about being out at a bar with other women teachers, and my mom’s friend had wanted to call it an early night. The other women said no, you have to wait for Jim Simmons. She told my mom how the other teachers had been giggling and laughing and trading secret glances. And my mom’s friend ordered another drink and waited, expecting Brad Pitt to walk through the door. But it was just this pasty guy with a gut and glasses and a Beatles mop top. She glued on a smile and tried to finish her drink quick and bail. Five minutes later she was blushing and touching his forearm and ordering another round.

That’s how good he was.

You couldn’t help but notice, in the papers and news reports after the killings, that Cindy Simmons was beautiful. I’m not telling you that to make the death seem more tragic or anything. Maybe you had to look at her in those pictures because to look at their four-year-old son and their baby daughter was just too much to bear. And when I tell you that in the photos in the paper and the news you couldn’t help but notice her breasts, so high and outsized on her body so that even modest flower dresses couldn’t hide it, I’m not saying it just to be lurid. I promise you it will matter later.

You’ll see. You won’t like it, but you’ll see.

The teachers taught us the best they could over those next few days, even though we were all electrified, all of us together in this storm cloud of mystery and fear and something else, something that we wouldn’t dare name. I remember Mrs. Capistrano the math teacher, who was married to Mr. Capistrano the other math teacher, trying to teach us algebra, x and y and the quadratic equation. But nobody could hear her over the sounds of our own blood. The lub-dub of our heartbeats chanting all-dead all-dead all-dead.

We put the story together like dinosaur bones:

Mr. Simmons had been at a teachers’ conference up at the lake, ninety miles north of town. Sunday morning one of Cindy’s friends was supposed to ride with Cindy to church. She called and called, got nervous when she never heard from her, and drove over to the Simmons house to check on them. Maybe she was scared, or maybe just annoyed in a way that must have ate at her later. She saw how the garage door hung open, with Cindy’s car parked inside. She let herself in the house through the garage.

She must have called out as she walked into the house. How loud her voice must have seemed to her. In the right kind of quiet your skull becomes a megaphone. She saw a footprint on the living room carpet in dried paint. The words DIE BITCH and SATAN painted on the walls.

What was there in the back of her brain as she walked through the silence? The things I want to know about her are things she probably doesn’t know about herself.

She went into the master bedroom and saw the red-black spatter on the wall above the bed, saw the unmoving lump of Cindy Simmons underneath it. She ran for help before even checking on the children, and she is lucky for that. It was the police who found their four-year-old son and infant daughter in their own beds, with their own spatter.

I don’t know much about that friend, but I am sure that sometimes she blinks and the corpse is still there behind her eyes. That’s how it works; I know that now. Some things you see burn so hot they brand themselves into your eyelids. Some things don’t leave until you do.

It’s so hard to write about this. I’ve been trying for decades. I’ve tried twice to write it as a novel, first before I got my first novel published, and the second time a few years later. That version ended up mutating into a whole other book about teenage criminals in the desert. So I tried to sell this story as a TV show last year. The first line of my pitch was the same as the first line of this story. The executives liked it but then the network decided they didn’t want to do a crime story with teenagers in the lead. So now I’m trying it like this, to get the story out hard and fast. But it does not want to come.

Maybe it’s because it feels wrong to lie about these things. To change the names but keep the corpses. I’ve never been interested in telling the story as true crime, even though maybe you’d like that version better. Maybe you want to feel it in your bones that this is the way it happened. You want to see the killer’s face. You want a rope of reality between you and the crimes. It makes you feel alive, doesn’t it?

So maybe the lies are just for me.

That Friday night after the murders, the crew—me and Matt and Chael and Zach and Joe—drove up into the hills. The air acrid with bad weed smoke. Higher than giraffe pussy, Matt always said. On old roads in the Ozark hills, up and down so fast that when we crested the hills the wheels lifted off the shocks and I felt in my belly what the birds must feel, just for a second before crashing down. It would knock loose the shotgun so that I had to kick it back under the seat.

We might as well talk about the shotgun.

The shotgun was real, it’s not one of the lies I’m telling you. Matt had gotten it in trade for a car stereo he’d stolen from a neighbor’s car. The barrels had been sawed-off a half-inch past the stock, poorly, so the mouths of the barrels wore jagged teeth of twisted metal. It looked as evil as it was. It was loaded. I know it was crazy that I drove around with it under my seat for so long. If you’d asked me why it was there, I would have said something like where else would it be? Like it was all a joke. Most of the time I even forgot it was there, at least with the front of my mind.

The front of my mind was focused on the murders. Death had never been so close to me before. I read everything I could about the killings. I watched the evening news. I talked about it until I worried that people could see the dark thrill at the heart of me. In those early weeks, though, everyone wanted to talk about it. In those first weeks the killings still felt like a mystery. Who would kill Mr. Simmons’s family?

That night in the hills, Matt said it first. “Shit, ain’t no mystery. Who kills women? Men do. Who kills wives? Husbands do.”

We might as well talk about Matt.

We’d been friends since second grade, when I learned about the boy who couldn’t have candy and had to give himself shots every day. I guess nowadays he’d have an insulin pump. He was a wonder to me, this boy who jabbed himself every day, who would let the hypodermic needle dangle loose from his side just to make the girls scream.

Matt’s mom worked third shift at the GE plant. She was shaped like she lived on Jupiter, like the gravity of this planet was heavier for her than everybody else. Matt had her genes. He was short in a way that made it hard for him with girls, which is why he clung to Donella so fiercely. A girl from the Holler with cutoff jeans and sky-blue eyes who covered her acne with foundation that made her cheeks look like stucco. The two of them matched well together because for both of them love was a knife fight. They would laugh and curse and fuck and cut each other up real good for a little while, until the bleeding got to be too much for one of them. And then they’d quit for a while and then they’d run the cycle again.

Matt was short in a way that surprised the men of the Holler when Matt came for them for hitting on Donella, came for them with his fists or a bat or a fold-out knife. With a violence behind the eyes that he came to honestly.

Our senior year, as the rest of us made our college plans or other escape routes, Matt split his time between us and Curtis. Curtis was this white trash Frankenstein’s Monster sewn together with prison ink and homebrew chemicals. He’d seen something in Matt that he could use, shape toward his own ends. Curtis scared me. Later on, I used his name in the book about teenage criminals. I made him a more honorable outlaw than the real one ever was. He’s dead now anyway.

I met Matt’s dad only once, by accident. We were at a restaurant and a man and a woman walked by on their way out the door. The man said “Hello, Matt,” and Matt said “Hi, Dad.” The man didn’t even break his stride. So I understood why Matt went out to Curtis’s place, the way you understand shipwrecked people turning to cannibalism.

The stealing was something else. Matt stole everything from everyone. He stole every lighter that was ever handed to him, and his mom’s prized Camaro, and I think he stole my car stereo once. He sat at Curtis’s feet, and Curtis shaped him—but the clay was already there for him to mold. In those days after the murder, Matt was stealing more, dealing more, fighting more. I can see now how for Matt high school was a plank he was walking, that once he reached the end of it there was nothing left but the fall and the splash.

Anyway, that’s what I try to tell myself.

“Men are funny,” Aurora said to me when I told her what Matt had said about Mr. Simmons. “I don’t mean ha-ha funny.”

I met her in a mosh pit. The most beautiful girl I’d ever seen, holding on to the front of the stage at a punk show while the big mooks slam-danced behind us. She had the same haircut I had, long on the top and shaved on the sides. She was funny and weird and she didn’t belong and didn’t want to. She was a first-generation Filipina American in the whitest city in America. She was a piano prodigy who sang in a punk band. We talked about everything except how she was going off to Yale next fall and I wasn’t.

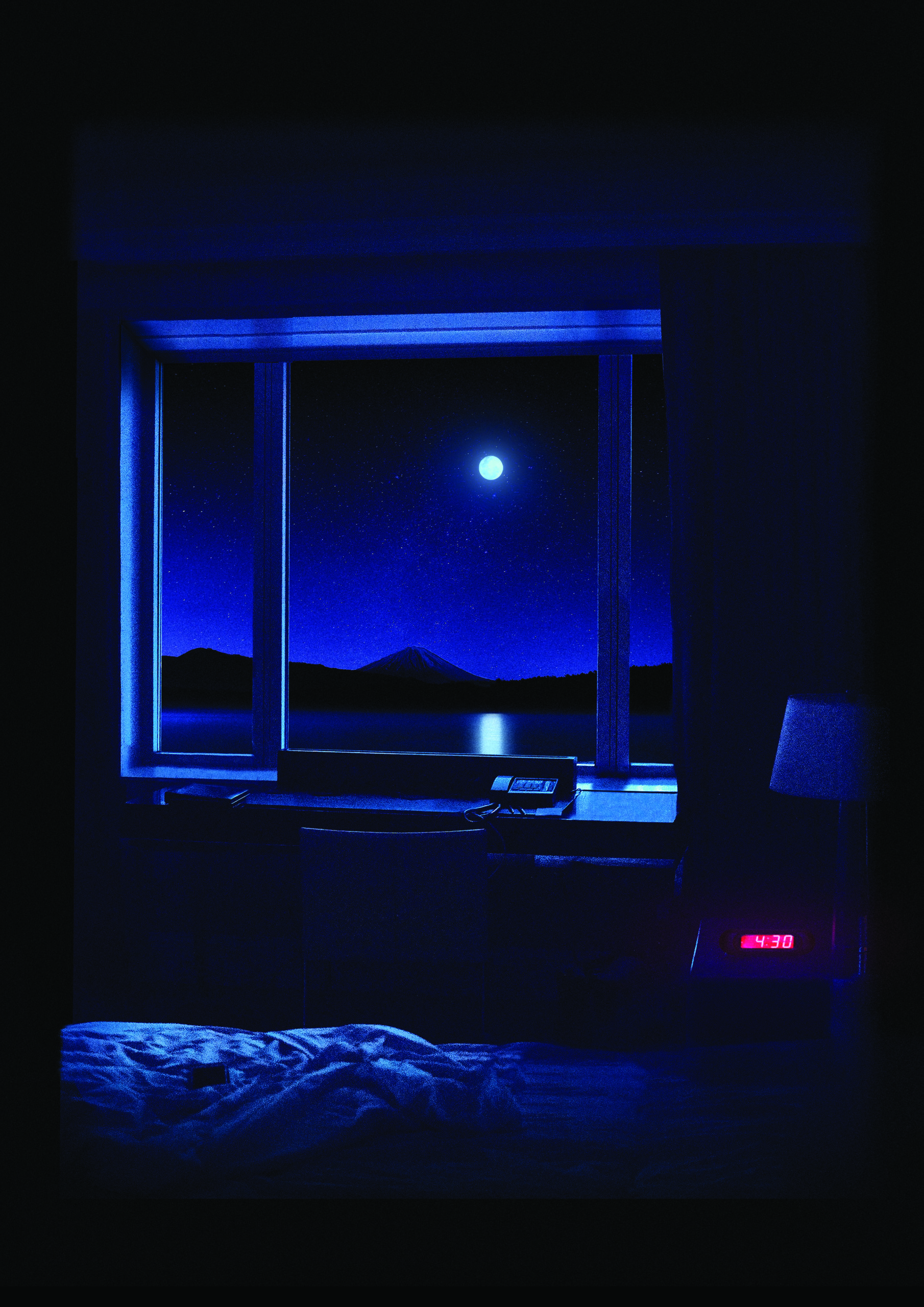

Her father was the city medical examiner. I know that sounds like something I’d make up for the story, but it’s true. So we knew things about the killings that the other kids never knew. She and I talked about the murders late into the night, on the phone in the dark. Or in backseats of cars or in our bedrooms when our parents were away, sweat-damp. Her little hands always cold against my neck. We loved each other enough to show each other the worst of us. To let each other see how much the killings thrilled us.

One long Saturday night we talked it out step by step. If it was him, how would he have done it? How would he have driven back from the lake in the middle of the night, the ninety miles on the highway? Did he play the radio? Did some song come on that chilled him, caught him by surprise, made him laugh with the irony of it all? We sat there and imagined him; we talked it through in real time. How he would not park in front of the house. Three a.m., that evil hour, nobody stirring, a dog or two barking as he walked down the street. How he would walk up to his front door quickly, that one moment of pure risk when a nosy neighbor could see him.

“Maybe he hesitated just inside the door,” Aurora said, a catch in her throat, fear and shame and something electric. Her eyes closed. She talked faster. “Maybe he stood there in the dark, like when I sneak out at night, trying to stay quiet, how the dark has a texture, how air in your lungs feels ticklish, and maybe he stood there, hearing his heart in his throat, blood-thump in his ears. And maybe he stood there like that and it felt like forever.”

Her eyes opened and they were wet.

“And maybe he thought ‘I could turn around now.’ But he didn’t.”

And we talked through the killing, step by step. He’d go to Cindy first. The only one who could fight back. Maybe she’d woken up, murmured his name in sleep-talk at the familiar sound of his steps. And then he’d brought the hammer down. And then he moved to the next bedroom. And the next.

“But why?” I asked her. “Why would he kill his whole family?”

She smiled through the tears.

“Men are funny,” she said again. “I don’t mean ha-ha funny.”

We sat in a thick silence.

“My dad has the photos in his office,” she said. “The crime scene and the autopsy.”

Maybe she wanted me to say no, to be the one who turned away. Or maybe she needed someone else there with her, to see these things that no one should see.

“I’ll look,” I said. “I’ll look with you.”

Even though the photos felt unreal, the blood too dark, the skin too white, everything grainy and lurid in the flashbulb pop of a police photographer, they were also the realest thing I’d ever seen. Too real to be believed.

I looked at those photos for only a few minutes. I’ll never stop seeing them. Aurora’s face was in her hands, peeking through her fingers. And I realized I was doing the same thing. Something ancient at the base of my brain said there is death here, look away. But there was another part of me that needed to see. That needed to know. To see the shining red divots on a woman’s head, a head that had been shaved to make the wounds easier to see. To see how death takes everything from you. It takes your pulse, your heat, and it takes the million thoughts and illusions that make up a human being.

I can tell you these things, but I cannot make you see them. I can’t make you see the blankness of the eyes, the purple stains on skin where the cold blood pooled. The children, and the horror that was done to them. I can say those autopsy words to you, contusions and exsanguination and blunt force trauma. These are just the facts. Facts are dry.

But the truth is wet.

I drove for hours that night, my eyes coated with what I’d seen. Shapes from the crime-scene photos recreated themselves in the shadows, in the shape of snow drifts. I got lost, let the stranger inside me steer. I turned onto Glen Oaks Street without even knowing it. But of course, that’s where I was heading the entire time. The address from the police files we’d just read. The place of the murders. I pulled to a stop across the street from the house.

Fingers of gray light flickered from between the blinds of a front window in what had been the Simmons house.

Someone was home. It couldn’t be Mr. Simmons. There was no way he’d live in the house where his family died. Even a killer wouldn’t do that.

Would he?

I opened the door.

I crept to the window. The venetian blinds were half closed. Through the gaps I could see slices of a woman, nude. The video was homemade, the image brined with static. I saw a mouth, a cock. I heard a distorted moan.

Something shifted on the other side of the glass. A man’s head on the other side of the glass, inches from me. That familiar Beatles mop top gently bobbing against the couch. I realized what he was doing, doing in the house where his family died, where specks of death still floated.

I moved away from the window, slipped, fell into the sharp coldness of frozen grass. The sky dead above me. Something radioactive at the core of me, invisible and sickening and hotter than the sun.

I was pitching a TV show once, a supernatural crime story about a drug that is also an alien that takes over a town in the California high desert, and an executive at a studio asked me what the difference is between terror and horror.

“Terror’s what you feel when you’re running from the wolf,” I told her. “Horror’s what you feel while you watch the wolf feeding on your guts. Showing you what you’re really made of.”

I didn’t sell the show.

As winter turned to spring, after the snow but before the thunderstorms, my friend Zach and I went to an all-night house party. We pulled the old sleepover trick, telling our parents that I was spending the night at his place and he was spending the night at mine. Our old friend Courtney’s parents were out of town. We had been closer with her in junior high, before the great sorting had put us in one camp and her in another. So the party was mostly the pretty people, the soccer guys and cheerleaders. Some older brother had bought the party kiddie booze, Boone’s Farm and peach schnapps and watery beer.

I never drank—although I’d put any other chemical inside my body that I could get hold of, alcoholism ran in my family and I feared booze like a lycanthrope fears a full moon. So I watched the others get sloppy and wild.

Amy C., queen of the dance squad, was there, drunk as I’d ever seen anyone to that point. She got sick, and after she emptied herself in the bathroom, Zach and I helped Courtney get her to Courtney’s bedroom so she could lie down. But she didn’t want to, and she fell on the floor laughing. She peeled off her shirt and used it to wipe her face. She sat on the carpet in her bra and jean shorts. Her laughs turned to sobs. Her eyes muddy with smeared mascara, her eyes alive and weeping. I turned away, trying not to look at her, half-hard in my pants and ashamed of it. Zach, whose face looked like mine felt, tried to give her his shirt but she slapped it away.

“I’m so worried about him,” she said. “He must be so sad, he must be so scared.”

“Amy—” Courtney said, real fear in her voice.

“Who are you worried about?” Zach asked.

“Jim. Poor Jimmy.”

Some deeper part of me put it together before I did. It coughed up the memory of the day of the murder, Amy keening in the hallway after the news broke.

“Is she . . . ?” I asked Courtney.

“She’s talking about Mr. Simmons,” Courtney said.

“He’s so sweet,” Amy sobbed. “So sweet.”

“Why the hell is she calling him Jimmy?” Zach asked.

“They’re in love,” Courtney said.

“Her and Mr. Simmons?”

“You can’t say anything,” Courtney said. “Promise you won’t.”

And I didn’t. But somebody else did. Amy’s parents sent her away. They took her out of school and sent her to an aunt in Waterloo, Iowa. And she never came back and she never said out loud what had been between her and Mr. Simmons.

Turns out it didn’t matter. Turns out the thing Mr. Simmons had was lots and lots of love.

Secrets have an inertia all their own. Once a few get free, others follow. Faster and faster.

The detective in the yellow sports coat set up shop again in the principal’s office, where we could see the girls coming in from across the hall in journalism class.

We saw Becky Polk go in and come out crying. We saw Sarah Gelson go in and come out crying. So many others. Too many to name.

As the girls talked to the police, word spread all over. It was the same week the rains came, came hard and like thunder, like they do every spring in the Ozarks.

I heard he bought Jennifer beer.

I heard Rachel and Annette went out with him and his friends to the Coral Courts Motel.

I heard there’s a house on Lone Pine, a house that’s just for partying. A fuck pad.

I heard it’s the house with the overgrown shrubs. The one with the brick chimney.

I found the house. I couldn’t have been the only one who looked. I drove to it late one night. Wind gusts creaking the trees. Flashes of faraway lightning.

The only dark house on the block.

The house stank of a million cigarettes, smoke baked deep into the walls and carpet. The air was ticklish against my skin. There were couches and beanbags everywhere. The sort of posters college kids hang on the walls. A TV set and a VCR. And there were rows of video tapes, all of them blank, a few of them labeled with tape and marker across the top. No names, just dates. I grabbed one and fed it into the VCR. It swallowed it down with whirring noises. The TV came alive with a loud blast of static. I killed the volume and taught myself how to breathe again.

The image bent and distorted, like the tape had been played many times. The colors were lurid and too real, like the murder-scene photos. Bodies in the night, darkness behind them. Mrs. Capistrano the math teacher, who was married to Mr. Capistrano the math teacher, naked on her hands and knees in a pontoon boat down on some lake. Men with their swimsuits pooled at their feet, one in front of her and one behind. The camera swayed, bands of light and static bent across the screen. My face warm in the gray light. I turned the volume up just enough to hear the splash of water, the grunts.

“Fill her up,” the cameraman’s voice said. “Open her up and fill her.”

The voice sounded choked, like his throat was swollen shut by desire. But I still knew Mr. Simmons’s voice when I heard it. The video bent and the images flecked with static, the way tapes got when you watched them too many times.

I almost didn’t hear the footsteps on the front walk. I killed the TV and ran back through the house, feet shushing against shag carpet, static sparks dancing, purple ghost lights blinding me in the dark. And I ran out into the night. Summer lightning flashed. The crash came a breath later. The storm so close.

They burned the house down that night. Maybe they saw me or heard me as I ran. But I don’t think so. I think whoever did it, Mr. Simmons or one of his friends, did it because too many people were talking, too many secrets were bleeding out.

I drove by it the next day to see. The house in the daylight, the front windows broken by the firemen. Water from fire hoses had shattered the front windows on either side of the front door, so the smoke poured out and left dark stains, like the smeared mascara of a crying woman.

Police tape across the door. Cops carrying out boxes of tapes, melted and black.

They arrested Mr. Simmons the next day.

He hired the same lawyer who got off the banker who killed his wife the year before. The lawyer called Mr. Simmons the fourth victim of a killer on the loose. A lot of people believed him. A lot of people still do.

Rumors swirled. They came from the adults now. About men trading wives, about men and young girls. About how it wasn’t just teachers.

People talked. About how Mr. Simmons had talked Cindy into getting breast implants, and how she hated them. How he’d talked a lot of other women into doing things, things they wanted to do and things they weren’t sure about.

The murders themselves began to fade, even for me. Mr. Simmons had been arrested, and for all my punk rock posing I still believed back then that the cops were there to do their job and that job was getting murderers off the street.

Sometimes time gushes like blood from a wound. Days passed in spurts. We graduated high school. I started making plans for going up to the big state school. Joe was going to be my roommate. Chael was looking at the army, and Zach was looking to move to San Francisco. Aurora was planning her move east. All we talked about was what was about to begin. We didn’t talk about what was ending.

We didn’t talk about Matt, and what was happening to him.

One evening that summer, the two of us drove around, smoking ditch-weed joints on country roads, the double yellow line chipped on old Route 66. The way the light smeared in the dusk. Those ancient hills.

Angry guitars on the stereo. Matt’s knuckles were scraped, one eye clotted with blood. He caught me looking at it. He said, “Curtis has got these problems, some guy fresh out of jail who thinks he runs the Holler. And we’re showing him the hard facts of things.”

A patrol car came up behind us at speed on the old country road. Fear chemicals filled me up. I was stoned hard on a country road with a cop car right behind us, headlights in the rearview. I gripped the steering wheel to hide how my hands shook. Matt’s eyes were flat in the dark as he looked me over.

“Do you have the shotgun?” he asked me. Not like he was scared the cops would find it. Like he wanted me to get it out.

I said, “Fuck that.” But he could hear the tremble in my voice.

“Get ready,” he said.

The cop’s cherries switched on in my rearview. Cold air came in through cracked windows to flush the pot smell. The sawed-off shotgun under the driver’s seat. Those moments when your life balances on the edge of something, two whole and completely different lives you could have lived depending on which way the coin tumbled. All I could think about was getting out. How close escape was for me. Maybe not for Matt, but for me.

I pulled the car over. Matt unbuckled his seat belt.

The cop car slid past us up the country road, roaring as it accelerated.

“You know what your fucking problem is?” Matt asked me, but his voice had deepened, gotten more of a Holler twang, so I knew that Curtis had asked him this same question in this same way. “Your problem is you think you’ve got something to lose.”

I came home that night still stoned, still scared, and I could hear my parents watching the news in the living room, calling to me. I didn’t want to go to them because I didn’t want them to see my bloodshot eyes, and I didn’t want them to see the fear. But they called to me again, like it was important, so I went into the living room, ready to be caught. My parents barely glanced at me. Their eyes were on the television. The local news. A floating chyron with the words CHARGES DROPPED. A photo of Mr. Simmons’s face.

It fell apart so quickly.

Mr. Simmons’s lawyer had noticed that the autopsy photos, the ones Aurora and I had seen, were numbered out of order. That there were photos missing. And so he hunted down the negatives, or somebody did, and they found the missing photos. Mrs. Simmons on the autopsy table, naked, with the detective in the yellow sports coat with his hands on her body, on her breasts. Later he’d say he’d never seen fake breasts before. That he didn’t mean anything by cupping them. He couldn’t explain why the junior medical examiner needed to take photos. Why they’d hidden them from Aurora’s dad. Why he’d had a smile on his face.

The lawyer took the photos to the prosecutors, who talked to whoever it was who could make those kinds of decisions. And they decided to keep it quiet. Which meant dropping the charges. Which meant keeping it quiet about Mr. Simmons and all those women, and all those girls, and they kept it quiet about all those other men who were a part of it too, whoever they were.

And maybe it really was the lawyer who figured it all out on his own, but I wonder about that. I wonder if maybe somebody didn’t give him a nudge. Either way the charges were dropped; the secrets were safe. A few had leaked out, sure, but that always happens. It wasn’t enough to hurt anybody or change anything. Just a little bit floating inside us, not doing anything. Like the lead in our blood.

Aurora sobbed on her bed. It was a week before she was leaving for Yale. Her suitcases were already on the floor, waiting to be filled. She sobbed for Cindy Simmons. For what they did to her. I reached out for her, and she pulled away from me. Like I was poison.

“It’s never enough for you men, is it? We’re never enough. It doesn’t even stop when we die. Our deaths aren’t enough for you. Nothing is ever enough.”

And I wanted to say not me and I wanted to say I’m different but I was at least smart enough to shut up. And anyway, I wasn’t so sure how different I really was. And so I sat there and I watched her cry, and when she stopped I watched her breathe. After a while I got up and I said goodbye to her. I said I was sorry, and even if I don’t know what I was apologizing for, I know that I meant it.

I sat parked on Glen Oaks Street. It was dusk and the light was beautiful. Summer had come. My escape was at hand.

The shotgun sat on my lap. I pressed my thumb into the splinters, wanting the pain of it, letting it crawl up my shoulder, pressing harder, like maybe I could get the pain of it all the way into my heart, lance it, let it bleed out the bad things that filled me. I pressed until blood wept.

Mr. Simmons pulled into his driveway. He got out of his car and walked up the drive with a bag of hamburgers and fries.

He walked to the door. I thought about what he deserved.

Our deaths aren’t enough for you, she’d told me. Nothing is ever enough.

I could see him torn in half there on the driveway. I knew it would only be justice.

I want to lie to you just a little more now, tell you I put my hand on the door handle, tell you that I almost got out of the car. But I didn’t. I sat there and I watched him walk into the house. After a while the sun set. I sat in the dark. I started the car and I drove home.

I thought about that life I could see just outside my grasp. The one where I would be free and whole and away from there. The one where I reached my potential. I thought that maybe I did have something to lose.

But I thought about other things, too.

The next day Matt and I got a pizza and some grape soda to play Street Fighter on my Nintendo.

While we were bringing the pizza into the house, I grabbed the shotgun from under the seat, stuffed it under my shirt.

“I’m tired of driving around with it,” I told him. “Like what the fuck, right? We could have got busted the other night. Not like I’m looking to shoot anyone.”

“Yeah, that’s a good move,” Matt said, “what with you being a pussy and all.”

When we got to my room I put the shotgun in my closet, under a pile of clothes. I did it with the door open, where Matt could see me. We played for a while. The pizza roiled in my guts. I liked to play Blanka, the monster from Brazil. Matt played Ryu, the hero. I lost more than usual. I tried to find the right moment.

I paused the game. I told him I had something to tell him. I could feel my pulse in my eyeballs.

“I saw Donella coming out of the principal’s office. When the cops were there. I didn’t want to tell anybody.”

I wouldn’t have used her name if she wasn’t on a float trip with her family down in Arkansas. I wouldn’t have done it this way if she had been in town. I swear.

“Bullshit.”

“I saw the list,” I told him. “I saw the list, from Aurora’s dad. Of all the girls Mr. Simmons had been with. Donella’s name was on it, Matt.”

Matt looked into my eyes to see if I was lying. I held that gaze. I let him see something true inside me, even if it wasn’t what he thought it was. He broke off the stare. He unpaused the game. We sat there in this storm of silence. I beat him three rounds in a row. Matt studied his fingers, watched them turn into fists. He got up and went into my closet. Maybe he muttered an excuse. I pretended I didn’t hear him rustling in the back. I pretended I didn’t see the lump under his shirt, clamping something down with his armpit as he mumbled his goodbyes.

After he left, I went downstairs and tuned the TV to a local station. Some endless car auction. I sat and I watched, waiting for the interruption I knew was coming. When they cut away to the newsroom I knew what they were going to say before they said it. I knew they’d throw up a picture of Mr. Simmons’s face. And then they did. And now I look back and I wonder what I was feeling, and maybe I’ve forgotten. But what I worry is, I wasn’t feeling anything at all.

I drove to Aurora’s place that night, late, after the story of Mr. Simmons’s death and Matt’s arrest had played itself out on television and in phone calls. You can see it, can’t you? How Matt had parked right where I had parked the day before, with the same shotgun in his lap. Waiting the way I had waited. But of course Matt got out of the car when he saw Mr. Simmons. He knew from Curtis how to get close, how to get that shotgun right up against Mr. Simmons’s back and pull the trigger.

I told myself that Matt was still a minor, and I wasn’t. I told myself that I didn’t make him do anything, that he made his choice. I told myself that even if Matt didn’t know it, everyone else could see the thing building in him, that it was going to come out, and all I had done was make sure it was pointed in a direction that did the world some good.

Isn’t it crazy how you don’t need to believe a lie for it to have power?

I drove to Aurora’s house that night. Sometimes when you sit on a dark street where no one is awake it feels like a cage. Sometimes it feels like you could do anything at all. I walked through the dark. I thought about Matt someplace in a cell. I could smell honeysuckle on the air and summer thunder coming. I went around the side of the house to Aurora’s bedroom window. I knocked on the glass, softly, our secret knock. She sat up in her bed. First scared and then smiling. I tried to look at that smile, burn it into my mind forever like all the terrible things I had seen, but mostly what I saw was my own reflection looking back at me. I wondered what she saw. If she could see me at all. If anyone ever had.

I told you I would lie to you, and I did. And now I will tell you the truth.

The story about the breast implants and the detective violating the corpse of a murdered woman really did happen, but it was in the case of the banker who killed his wife and got away with it the year before Mr. Simmons killed his wife and got away with it. Mr. Simmons got set free because of a witness who maybe lied or maybe got confused. It’s not as good a story. So I used the terrible detail, scavenged it from the dead. Because that is what I do.

Aurora and I tried to stay together, but of course it fell apart that first semester of college. But listen: everything ends, every fruit fly and every blue whale and every diamond and every star, and if it all falls then nothing does.

Curtis really is dead. He died in a hotel-room meth-lab shootout with the cops. Like something I’d write in one of my books. I’ve tried to use his death in a few different stories, but it hasn’t quite worked yet. Someday.

Matt is dead too. He died in his thirties of complications brought on by neglected diabetes and heavy drinking. Donella, who watched over him in those last days when he didn’t have anyone left to stand for him, called me the day before he died. She told me he wanted to talk to me. And I didn’t call him, even though I knew it was the last day. Maybe I was angry, maybe I was scared, but either way he tried to end with us in peace and I didn’t call him back. And I have to live with that.

You get older and the thing between you and the world gets thicker, stained, harder to see through. But there’s plenty I can still see. I can see I was right about a lot of things back then when I was an angry punk kid who wanted to burn the world down because adults are selfish and cruel and scared. And the fact that I’m one of them now only proves the point.

I left, and I never moved back. I took my love of the darkness and I shaped it into something I could live off of, something I could sell. Like I’m doing right now. Because that’s the best thing I can figure to do in this world we’ve made.

I don’t know if I ever reached my potential, or if maybe I’d already reached it back in that savage year. What I do know is, the thing I left my hometown to find, I never found, and the thing I left to run away from has stuck to me the entire time. The only peace I have found is to see that it will never leave me, and learn to live with that, and that helps me.

Sometimes. ![]()

Jordan Harper is the Edgar Award–winning author of the novels She Rides Shotgun, The Last King of California, and Everybody Knows, and the story collection Love and Other Wounds. He lives in Los Angeles, where he works as a writer and producer for television. He was born and educated in Missouri.

Illustration: David O.