When James W. Marshall found shiny metal that turned out to be gold in 1848 near Sacramento, he intended to keep it quiet, but his secret reached around the world and brought more than 300,000 people west. The California Gold Rush would last until 1859—long enough for some souls to follow in Marshall’s footsteps, and long enough that the majority of the rest would come up empty. And while that original pursuit would fade, the dream would survive. One hundred and seventy-five years later, we still go west to find our fortunes, to start new lives, and to escape from old ones. California indeed remains that shiny beacon of gold—that yellow-brick road that lures us to the dream factory—but instead of the Sacramento area, it’s the southern half of the state that calls to some when we become transfixed by the movies that reach us when we’re young.

If we still chase our dreams out west, we go southwest when we’re restless, when we have a greater sense of adventure, and when we can’t just sit idly by basking in the yellow-brick-road-hued sunlight. As peaceful as it is dangerous, the American Southwest is defined by intense duality. It’s as easy to get overwhelmed by the vast, open landscape as it is to find inspiration in its beauty. This universal feeling is a favorite of filmmakers, whether they’re shooting quirky indie films set in the present day or big-budget epics set in the distant past. There’s something about the Southwest that is perfectly suited to cinematic storytelling. Paris, Texas is Paris, Texas because we need the enigmatic, near-Biblical image of Harry Dean Stanton wandering through the desert in pursuit of something we haven’t yet deduced. As Martin Scorsese famously said, “John Ford made Westerns; I make street movies.” Mean Streets in Texas would be a Western, no matter when the picture was set, because the same DNA is there and the setting dictates all.

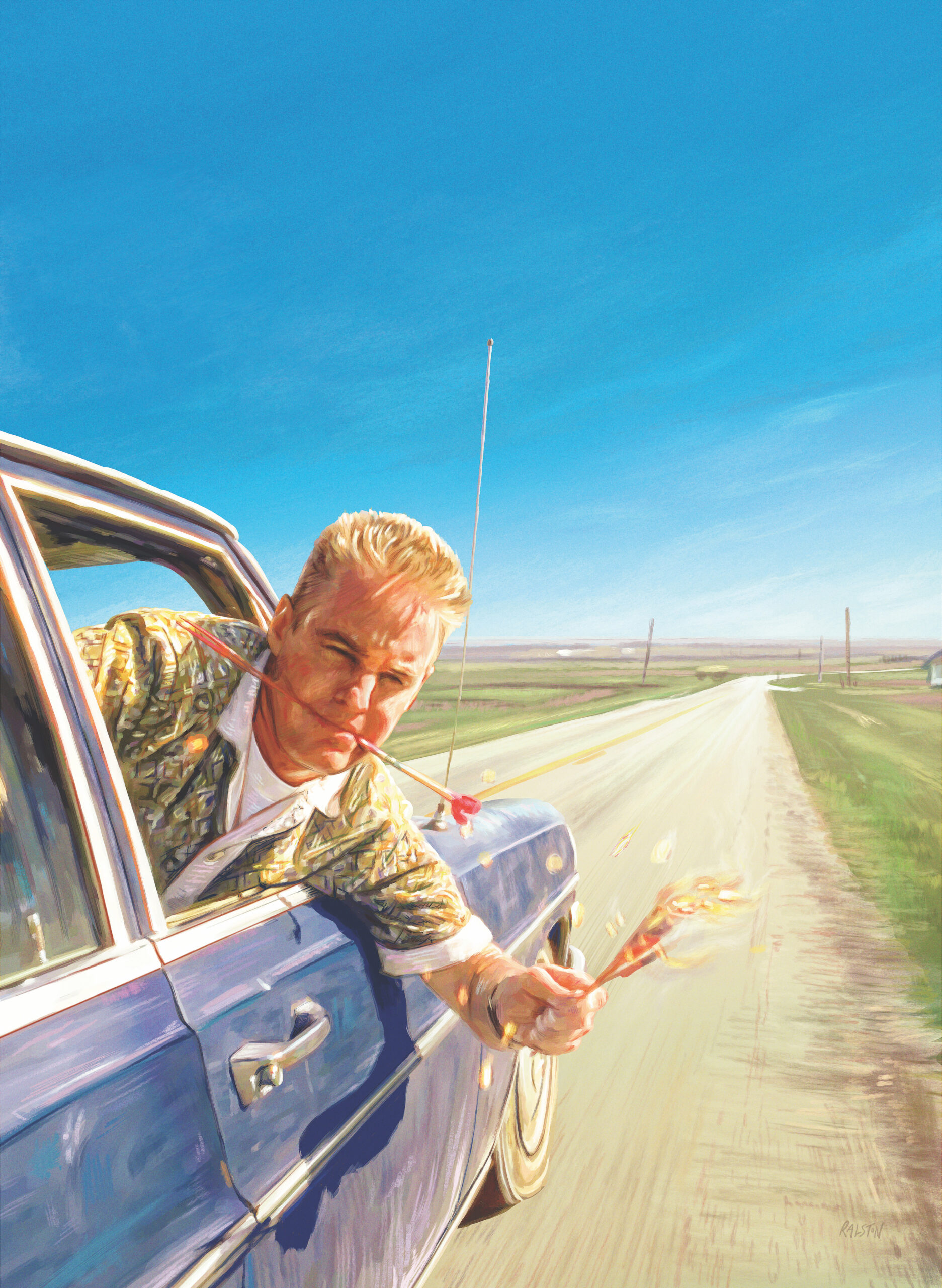

One of Scorsese’s ten favorite works of the 1990s, director Wes Anderson’s feature-film debut Bottle Rocket (1996) defies classification. Although Bottle Rocket wears its influences proudly in its frames, it does the film a disservice to simply call it a Western. Scripted by two former University of Texas at Austin roommates, Bottle Rocket was firmly rooted in ’70s existential crime fare in its earliest form. But as Anderson and his co-screenwriter, Owen Wilson, began to find their voice and pull from their own lives—including their friend and co-star Robert Musgrave, who helped set the tone—their lightning-in-a-bottle cinematic firework developed into something much more than a standard crime flick. There are casually tossed-off jokes that only sink in minutes later, and instead of laughing, we catch ourselves smiling because the film’s distinctive voice, its naivete, and indeed its earnest imperfections win us over. A hybrid genre work that mixes humor with pathos, Bottle Rocket is a coming-of-age crime dramedy romance with a southwestern spin all its own.

The film could’ve been a dark Western noir, had it been made without the humor and heart of the people who created it, but it has more faith in humanity and greater affection for the adventurous spirit of the Southwest than say, the masterful There Will Be Blood or No Country for Old Men, which were also set in Texas and released roughly a decade later. In a key line from the film, the irrepressible, ambitious character of Dignan—wonderfully played by Wilson—rallies a friend by the sheer fact that he’s “trying” to do so and always will, and that’s the beating heart of the Southwest. In a way, Bottle Rocket is the most unusual of Anderson’s early films because it feels the most improvised and the most organic. It has room to breathe, it meanders, it goes round in circles like Dignan’s dear friend Anthony when he’s running in the Arizona desert. Anderson and Wilson’s film feels like it was made by its characters because it was, although it was shepherded by terrific mentors like Kit Carson, Polly Platt, and James L. Brooks, who led to its getting made at Columbia Pictures, and was carefully planned out in notebooks similar to the way Dignan maps out his seventy-five-year plan to become a master criminal. Graduating with a degree in philosophy, Anderson had always dreamed of moving to the city of Scorsese. Although New York is the place where he would spend the majority of his adult life and craft his Salingeresque masterpiece The Royal Tenenbaums in 2001 with collaborator Wilson, the idea of setting a film about dreamers overwhelmed by adulthood in a landscape that can be overwhelming could not have been lost on him. It’s a restless work that’s as much an extension of the restlessness of the Southwest as it is of the restless creators that Platt affectionately nicknamed “the Bottle Rocket boys.”

Steeped in Wilson’s and Anderson’s love of crime movies and Westerns from days gone by, Bottle Rocket is filled with nods to the masculine allure of the outlaw. The setup is blissfully simple. It centers on three Dallas friends in their mid-twenties who decide to become petty criminals and apprentice under Thief star James Caan’s veteran thief, just to have something to do and to give their lives what they perceive is a jolt of excitement. Caan’s character, given the deceptively meek name of Mr. Henry, runs a landscaping company as a front dubbed the Lawn Wranglers. And as we soon discover, Wilson’s misguided yet good-natured schemer Dignan—the least economically advantaged member of the trio—worked for Mr. Henry before being unceremoniously fired . . . because it turns out that someone still needs to do some actual landscaping now and then.

At the start of the film, Dignan reunites with Anthony (played by Owen’s equally charismatic brother Luke Wilson), whom we first meet while he’s pretending to escape from a voluntary stay at a psychiatric hospital in Arizona, where he checked himself in for exhaustion despite, as his much younger sister Grace (Shea Fowler) chides him, never having worked a day in his life. Endlessly on repeat, it’s the loyalty of these friends—even when they’re doing something as pointless, childish, and delusional as robbing Anthony’s house in a practice run for their first big score—that boosts the morale of this unlikely gang when they’re feeling overwhelmed. As the two make their faux getaway on a bus back to Texas, Dignan pulls out his notebook of carefully constructed, overly ambitious plans for the next seventy-five years and creates a myth for their future as famous outlaws.

Dignan, more than any other charcter in the film, embodies the spirit of the Southwest. He gets up each day and tries to fight the elements, pushing that rock up the hill the hardest way possible without asking why and knowing that more often than not, it’s going to tumble back down. Similar to the way that people are lured to the Southwest by the promise of adventure—reinventing themselves along the way with new backstories in order to position themselves for greatness—Dignan’s childlike desire to embellish the simplest of robberies with flourishes like pole vaulting and explosives gives him a mythic status, if only in his mind. Spinning elaborate yarns, drawing intricate diagrams, mapping out the future, Dignan lays out his schemes like he and Anthony are preparing to pull off a great train robbery with Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Like the heroes of George Roy Hill’s film, who similarly create their own imagined future in Bolivia, Dignan and Anthony seek some new mythic destination where adventure awaits around every corner.

Back in their old stomping ground in Texas, Anthony finds himself depressed by Grace’s disapproval, especially when he learns that his younger sister has told her grade-school friends that her brother is a jet pilot. (Anderson and Wilson know that even a young girl in the Southwest is drawn to adventure.) Trying to build Anthony up like he’s James Caan leveling with Tuesday Weld, in a hilarious homage to Thief that’s also one of the most quotable lines of the film, Dignan asks Anthony what his kid sister has ever done with her life that’s so special. It’s a wry observation that, in what would soon become Anderson’s signature style à la Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums, and Moonrise Kingdom, proves the clear-eyed kids are far more intuitive and honest about life than the adults who fill his meticulously balanced frames. When Anthony admits that the fiction of working for Mr. Henry as a thief isn’t really doing it for him right now, Dignan earnestly asks, “Does the fact that I’m trying to do it, do it for you?”

And of course, it does. They will always try to do “it,” and that’s enough to keep them going because they care. It’s a thing that set the film apart from so many other movies in the early ’90s genre heyday of Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez. Bottle Rocket is easily the warmest, wittiest, least cynical crime movie made after the legendary Sundance class of ’92 changed everything with films like Reservoir Dogs and El Mariachi. Dignan and Anthony are dreamers. They need their myths, their stories, and they’re fully aware of Western lore when they shoot guns in the desert like John Wayne and Lee Marvin in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, even though the character they have the most in common with is the bungling Ransom Stoddard. Sacrificing the truth of a selflessly heroic act turns James Stewart’s character into a legend. And it leads to that film’s most famous quote: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” As a narrator of his own myths, Dignan echoes that sentiment, like a child rewriting his own bedtime story night after night to make himself the main character.

Put more bluntly, the protagonists in Bottle Rocket are “fuckin’ innocent,” as Dignan states near the end of the movie after the gang unsuccessfully robs a cold storage facility. When he says this, he doesn’t yet know they’ve been set up by James Caan, who, in his small yet significant supporting role, is the first in a long line of flawed father figures who will fill out Anderson’s filmography. Repeatedly in Anderson’s films, introspective young males with daddy issues seek out the approval and guidance of more overtly macho, manipulative men—John Waynes to their James Stewarts—brought to life by James Caan, Bill Murray, and Gene Hackman in Bottle Rocket, Rushmore, and The Royal Tenenbaums respectively. Curiously, we never see the parents of the main characters in Bottle Rocket, as we would in future Anderson films, perhaps because they would put a stop to the mythic quest for adventure with a much-needed reality check.

Serving as a foil to these fuckin’ innocents, Andrew Wilson (Luke and Owen’s older brother) co-stars in the movie as Future Man, the responsible older brother who says memorably sardonic things like “Just because you’re a fuckup, it doesn’t mean you’re not my brother.” Future Man is the older brother of Bob (played by Robert Musgrave), the wealthiest of the three leads whom Dignan constantly dresses down with dry, cutting remarks. Future Man’s sense of superiority leads to a showdown with Mr. Henry, albeit one that is considerably more low-key than the shootout in a traditional Western. Instead of bullets flying in the street outside a saloon, this battle of wits plays out in high-key lighting inside the dining area of a Dallas country club, where Mr. Henry puts bully Future Man in his place for being rude to Bob. The reason it works so well is because, before we fully realize that Mr. Henry is in fact a con man, Future Man is presented as the film’s villain. The scene illustrates why Mr. Henry is such a hero to Dignan—he’s awed by his macho toughness, as is Bob. Like the character in a Western who is manipulated into betraying his friends, Bob is as easily swayed as the others in his allegiance to Mr. Henry, partly because he fuels their sense of danger and adventure.

The outlaws in Bottle Rocket are hungry for adventure because they see it in pop culture. And the film culls from pop culture in ways that feel far more natural than Tarantino’s impressive yet overly stylized and self-referential Reservoir Dogs. For example, one of the film’s most oft-quoted lines, “On the run from Johnny Law; it ain’t no trip to Cleveland,” was taken from an old episode of Miami Vice. And in the shorter, black-and-white version of Bottle Rocket, which Anderson and Wilson made first and would propel them to Sundance and Hollywood, Dignan and Anthony discuss Huggy Bear from Starsky and Hutch while planning a burglery. Which just goes to show that when reality isn’t exciting enough, they turn to fiction.

Pulling off a heist puts them at the center of a larger-than-life story, even if the stakes are so low that the only real conflict comes from Dignan’s excessive planning. Everything in Bottle Rocket is low stakes—from the way the guys rob a bookstore for a few hundred dollars to the nonchalant way Anthony flips through a book on World War II planes during the concluding heist—because the reality of a robbery is far less exciting than the Butch Cassidy–worthy myth they’ve created in their minds. In keeping with these minor stakes, they decide to hide their identities by going on the lam, although we seriously doubt anyone is really looking for them. While needlessly on the run, Dignan, Anthony, and Bob shoot off fireworks that are an exciting yet fleeting diversion, which is something that James Caan saw as a titular metaphor for where the characters are in their lives. It’s also around this time that the film works in the quintessential Hollywood style note, namely that one of the characters must fall in love.

Luke Wilson’s Anthony is a different mode of man and one that Dignan hasn’t quite grasped can be appealing to women who are tired of the macho bluster of cowboys and outlaws. Just as the more sensitive persona of James Stewart opposes the John Wayne ideal of manhood in Liberty Valance, Anthony is the opposite of everything Mr. Henry stands for. He’s honest, polite, and vulnerable. In the opening sequence when Dignan is kindly led by Anthony to believe he’s helping him bust out of the mental health clinic, we notice that the beautiful female patients are the first to say goodbye to Anthony and thank him for his help. And in another early scene, Dignan, obviously uncomfortable with talking about what he calls “emotional disturbances,” tries to get Anthony to downplay his past when another attractive girl arrives at Bob’s house with Future Man. Yet much to Dignan’s bewilderment, she is immediately drawn to Anthony, and seemingly more intrigued by him when he explains that his existential crisis was triggered by being asked one too many questions about water sports with his rich friends.

In an ironic touch given his history with water, Anthony—who, in his own words, is “incredibly unhappy”—is in the swimming pool at a roadside motel when he first spots employee Inez (Like Water for Chocolate’s Lumi Cavazos) pushing a housekeeping cart. An adorable mutual attraction plays out between the pair as Anthony starts joining Inez on her rounds cleaning the motel. Although she’s from Paraguay and speaks very little English—and he has no understanding of Spanish—their chemistry is palpable. Anthony’s openness and ease quickly lead to a physical relationship, that in a decidedly unmacho move, he boldly and sweetly calls love.

In Inez, we see another side of the Southwest. She’s an immigrant who has traveled to Texas in search of a better life, yet someone who isn’t in desperate need to create a mythic adventure narrative for herself. She also has responsibilities to her younger sister, as we learn in a surprisingly tender scene with Anthony looking at a photo in Inez’s locket and assuming it’s a picture of her, only to discover it’s her sister, then asking to keep it anyway because she looks like Inez.

The contrast between the two—the way that Inez is practical about the future and hardworking, both in terms of her responsibilities at the motel and in learning English—helps Anthony wise up and grow up. Eventually he takes a cue from Inez and begins working for the first time in his life. Back in Dallas, Anthony picks up three jobs while staying with Bob. Despite the fact that Bob—whose globe-trotting parents own a home designed by Frank Lloyd Wright—is better off than Anthony, together they burn the candle at both ends delivering newspapers (a childlike job for a “fuckin’ innocent”), working construction (where their peanut butter and jelly sandwiches are stolen by burly coworkers), and serving as valets.

Things take a turn when our posse of wannabe outlaws bands together to rob a cold storage plant, for no other reason than Dignan, with the blessing of Mr. Henry, gets to plan the logistics of the heist himself. While we never feel like they’re in any real danger, Anderson and Wilson’s script does introduce a note of pathos. The adult world can be blunt, violent, with real bullets being fired instead of the fake ones depicted in a movie. We first see this tendency toward melancholy when Dignan discovers that he unknowingly gave all the money from the bookstore robbery to Inez in an envelope before they left the motel. He’s hurt enough that when he doesn’t feel better after throwing a boulder at a beat-up old car, which is something his misguided hero Mr. Henry might do, he slices Anthony’s nose with a screwdriver and draws blood. We witness this tonal shift once again, at the end of the film, after Dignan ventures back into Hinkley Cold Storage, where he is inevitably captured by the police and the officers deliver a series of brutal gut punches as penance for making them run. Better than a gunfight at the O.K. Corral, his takedown by the cops nonetheless jars Dignan into realizing—however temporarily—that there are real-life consequences to the myths he’s made up in his mind.

After learning Bob’s house has been leisurely emptied by Mr. Henry, who was planning his own robbery during the trio’s decoy heist, Dignan lands in jail. Their attempt to pull off a legendary score ends almost as soon as it began, as Dignan, a little more subdued than before, says goodbye to Anthony and Bob. In a final nod to the Western genre, Dignan passes along the belt buckles he’d made for Mr. Henry and the gang. Still, he remains innocent enough that he tells Anthony (who’s reunited with Inez) and Bob (who’s reunited with Future Man) that he has no hard feelings about his father figure’s betrayal. Then we see one last flicker of the aspiring outlaw we met at the beginning with the seventy-five-year plan that didn’t last more than seventy-five days. The film ends with Dignan staging a mock escape, as his friends’ eyes flash in a panic about what to do, and only then do we realize that, like Anthony’s runs in the desert, Bottle Rocket is cyclical. “Isn’t it funny how you used to be in the nuthouse and now I’m in jail?” Dignan asks before he salutes Anthony farewell. And just as Anthony has grown up by the end, we know Dignan the fuckin’ innocent never will. ![]()

Jen Johans is a three-time national award-winning writer, film historian, critic, essayist, lecturer, and creator and host of one of Vulture’s favorite cinema podcasts, Watch with Jen. As a journalist and critic, she has written for and worked with such outlets as FilmIntuition.com, the DVD Netflix blog, IndieWire, Slate, the Phoenix Film Festival, the Scottsdale International Film Festival, Film Movement, Scottsdale Public Library, Hardboiled Wonderland, Flixster, and Blogcritics. She is based in Phoenix, Arizona.

Illustration: Tom Ralston