I read Cormac McCarthy’s All the Pretty Horses (1992) back when I was twenty-one. In broad and irresponsible terms, it is a road novel with detours onto dirt tracks and camping out in the open countryside. It’s also a rite-of-passage novel: two youths, John Grady and Lacey Rawlins, travel into the wild side—neither American nor Mexican—of the Coahuila border territory and on their way experience love, violence, and death.

The book mesmerized me. It had me turning somersaults. It was a home run, out of the park. It made me see my home landscape—the Coahuila desert—differently. For the first time, I was able to perceive my surroundings in a literary way.

Shortly afterward, I read Daniel Sada’s Albedrío (1989), which reinforced that lesson: what you see every day can be your source material. The novel—Daniel once told me that it is the most personal of his works—tells the story of Chuyito, a child living in Castaños, who runs away with some Romani Mexicans who come to town to put on their show: the projection, with the minimum of equipment, of an incomplete movie. Another rite-of-passage road story. And a story of love and boundaries.

I can sum up the teaching that filtered through into my novice-writer, young poet’s brain in these fundamental lessons: Don’t go out searching for your subject. You have to look at, enter into, what is around you and come to terms with it.

Years later, when the time was ripe, I started out on that journey toward oneself which involves returning to the home that, given fresh meaning on the road, is not only a point of departure but also a landing strip. Central Power Battery of Oa.

From my reading of McCarthy, I have a memory that I like to recount. There’s a passage in Pretty Horses in which one of the boys arrives in Monclova. The scene opens as he comes out of a pharmacy on a corner of the main square. He crosses the street and the square and sits on a bench facing the church. He looks at the bell towers, one on either side of the door, and listens to the call to Mass. He starts walking again and comes across a newspaper the wind has blown down the street. He picks it up, reads it, then starts walking again and reaches the main avenue that farther off becomes the highway to Saltillo, 120 miles south.

Reading that passage blew my mind. The events were happening at that very moment—well, the timeless time of the reader—in my own city, not far from where I was. I left my home on the border between Monclova and Ciudad Frontera, walked to the avenue, boarded a bus, got off minutes later in the center of the city that many people still call the Steel Capital, and retraced the footsteps marked out in the novel. I guess a couple of hours passed between leaving home and returning. I was happy. There was a secret joy in knowing that Cormac McCarthy must have walked those very streets, that a few decades before he must have breathed the same air, and that the city in which I’d been born and grown up would have seemed to him a good place to set a couple of scenes in his novel.

Yes, I noticed some discrepancies and compared the information in the novel with the terrain: the church has only one bell tower. Almost all the rest fit: the long street along which the character walked was Calle de la Fuente, which connects with Bulevar Harold R. Pape and, farther along, becomes Federal Highway 57.

While I was thinking about how to write this, I wondered if I should quote the exact passage; which part to transcribe, which to paraphrase. I quickly flicked through my copy of the book. The first time I read the novel, I’d borrowed it from someone and so couldn’t underline anything. I’m one of those old-fashioned readers who return borrowed books. Or at least I was then. My own copy, bought many years later, is hardly underlined at all. For a time, I refused to do this to the books I felt would accompany me through life, thinking that it made no sense to mark the whole text. So, as I’ve never been completely sure just where those pages are, I started looking for them.

But I gave up the search. I was afraid that my memory was faulty, and that the passage wasn’t the same, was less impressive than I remembered, or that I’d quite simply made it up.

In any case, exactly what had happened almost twenty years before? Did I really rush out of my house to retrace the route taken by the character? (John Grady, to the best of my recollection.) Why is my memory of that quest so vivid?

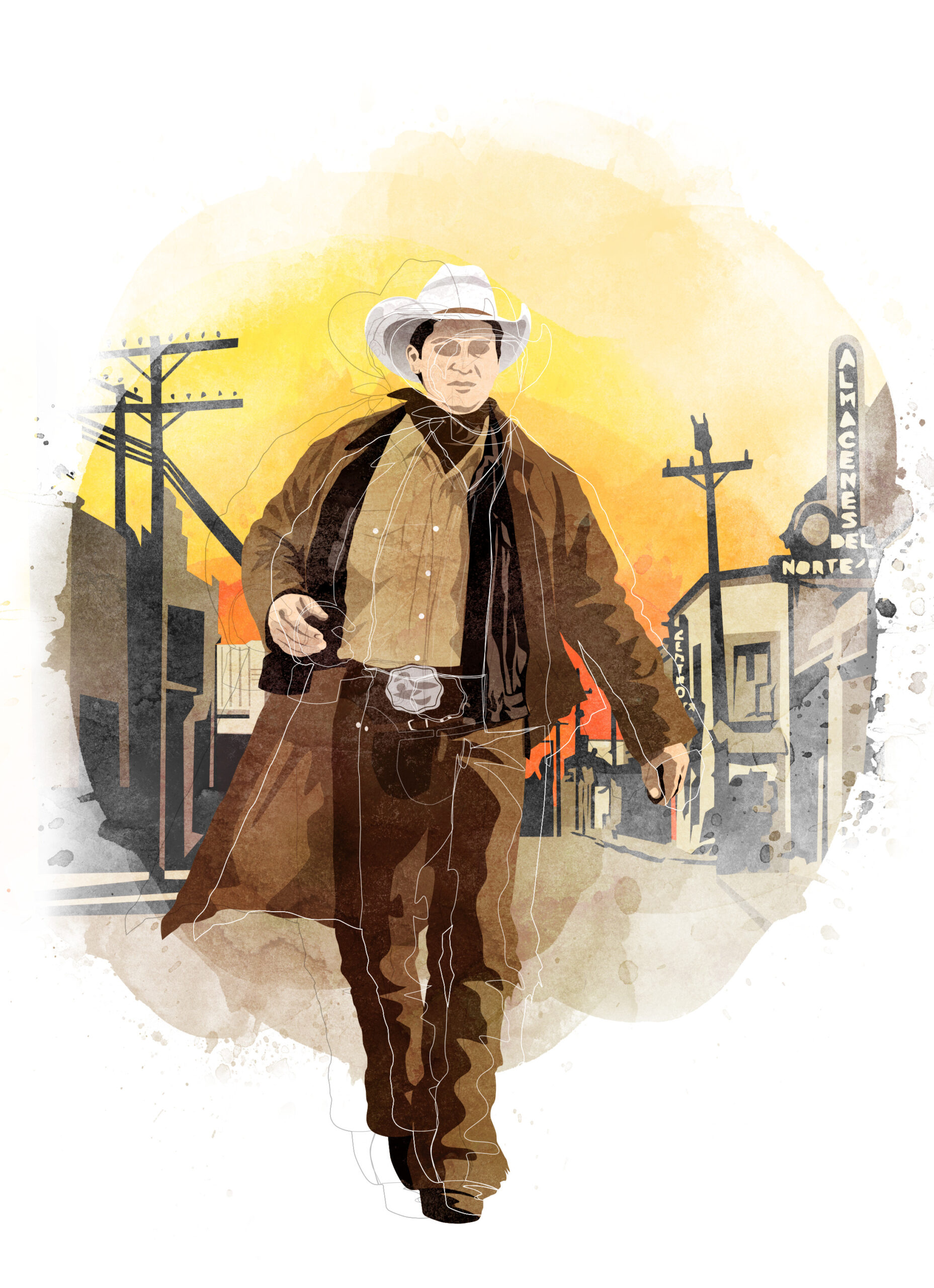

I always said I wanted a photo of myself coming out of the pharmacy. Boots, hat, black-and-white filter, the whole kit and caboodle.

One day, walking around the downtown, as I neared the location of the store, my desire to take that photo grew stronger, but then I understood it wasn’t going to be possible.

I was too late. The pharmacy had been demolished.

Five or six years have passed since then. Strangely enough, no other building in downtown Monclova has suffered the same fate. Now there’s only a flat rectangle between the stores and houses, a little rubble, the occasional patch of mosaic floor tiles.

I can’t remember the name of the establishment and don’t intend to check it out.

In my head, it has a name that says more to me than San Pablo, Guadalajara, Del Ahorro, or any of the numerous franchises in every Mexican city that today promise relief for pain and sorrow at affordable prices. McCarthy’s Pharmacy was a loner, a local business invisible to the rest of the world; a place where I sometimes bought magazines and pills, and where time passed unhurriedly over the eye-catching objects that had nothing to do with its course; objects displayed in the window but unavailable inside: toys, souvenirs, ornaments.

Every time I see that desolate patch of urban Monclova on which nothing has, at the time of writing (February 7, 2018), been built, my heart sinks a little. Reality allowed a beloved fictional scene to be snatched from me. Convergences like that don’t happen to me every day, and then a front loader comes along and snatches them away. “Who will buy me an orange in consolation?”

I closed my copy of the novel and let the search lie. A few days later, I began writing in free fall.

Demolishing a building is one thing. Demolishing one of your own memories is something very different. All the better. Nothing grows again, nothing can spring up where memory has failed or collapsed.

Let anyone who dares carry reality to their home keep it. I opt for the trinkets of handmade nostalgias: those slight souvenirs of the memory. A plastic plant, an oriental scene in a glass box, a ball with faded colors. Everything covered in dust. Brilliant objects behind the windowpane of memories. Preserved in their delicate fullness beneath the light of longing. ![]()

Luis Jorge Boone (Monclova, Mexico, 1977) is the author of more than twenty books, including the poetry collection Bisonte mantra, the short story collection Suelten a los perros, the novel Toda la soledad del centro de la Tierra, and the book of essays Cámaras secretas: Sobre la enfermedad, el dolor y el cuerpo en la literatura. He is a member of the SNCA of Mexico. He has received the Inés Arredondo Short Story, Elías Nandino Young Poetry, Ramón López Velarde Poetry, Gilberto Owen Literature, and Agustín Yáñez Short Story awards.

Christina MacSweeney is an award-winning translator who has worked with such authors as Valeria Luiselli, Daniel Saldaña París, Elvira Navarro, Verónica Gerber Bicecci, Julián Herbert, Jazmina Barrera, and Karla Suárez. She has also contributed to many anthologies of Latin American literature and has published shorter translations, articles, and interviews on a wide variety of platforms.

Illustration: Alvaro Tapia Hidalgo