When I think about the realm that extends through The Wizard of Oz and into the films of David Lynch, I think of several childhoods: Lynch’s, my father’s, and Dorothy’s in the 1930s and ’40s; my own in the 1980s and ’90s, during Lynch’s cinematic heyday; and my one-year-old daughter’s now, as she awaits whatever images and ideas will impact her psyche in the way that Oz impacted Lynch’s and his work impacted mine.

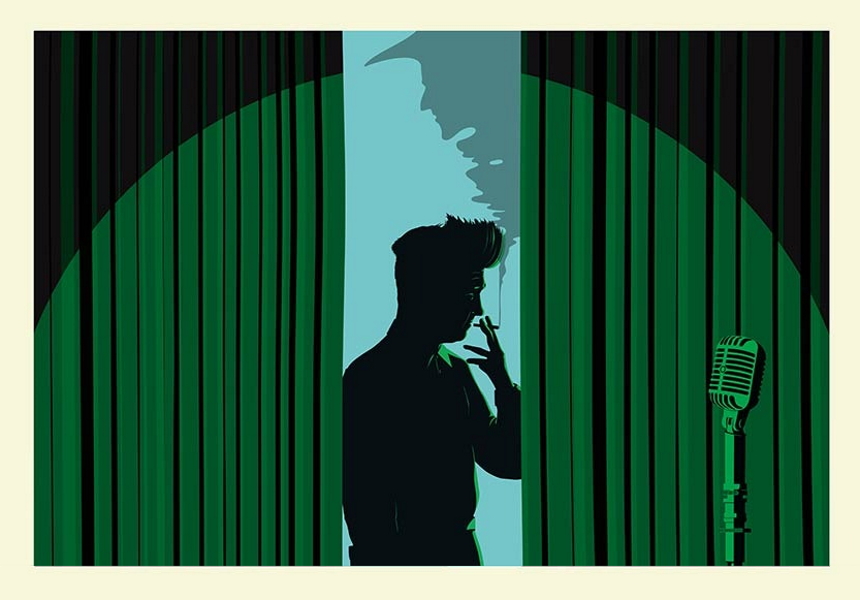

Alexandre O. Philippe’s 2022 documentary Lynch/Oz details the many points of connection between the two halves of its title, in the form of extended monologues by directors like John Waters, Rodney Ascher, David Lowery, and Karyn Kusama. Beneath these monologues, Philippe creates a seamless world of expertly chosen clips, weaving through red, blue, and green curtains to open a space in which Oz and Lynch’s filmography exist not as discrete works but as a unified field, our collective memory made manifest.

As I explored this mental space, I ended up back in the Pleasant St. Theater in downtown Northampton, Massachusetts, where I went to see Mulholland Dr. on the tiny basement screen with a friend on a Sunday afternoon in eighth grade. Two and a half hours later, we stumbled out shaken and changed, shocked in the best possible way, not just at what had occurred in the film’s world, but at what had occurred in our own—in what had been proven possible just as we were on the cusp of adolescence, itching to set out on the long road to maturity. We couldn’t believe how easy it was to step through a curtain, descend into the butter-smelling bowels of a rural art cinema of the type that hardly exists anymore, and enter a world as simultaneously alien and familiar as the one Lynch had prepared for us. How could a six-dollar ticket encompass an experience of that magnitude? We hadn’t thought such immersion possible after the permanent head trip of childhood faded—indeed, we’d thought that growing up meant renouncing this possibility—but as we climbed back up to the lobby, we realized we’d had it backwards: from that point on, adulthood came to mean doing whatever it took to find and cherish this kind of immersion, not as a means of denying the hard truths of growing up but as a means of accepting them and proceeding deeper into life’s mysteries from there.

The moment when the beaming ingenue played by Naomi Watts arrives to seek her fortune in Hollywood at the outset of that film mirrors the moment when Dorothy arrives in Oz, both of them excited but wary, seeking home while also desperate to leave home behind. The feeling of going to Mulholland Dr. that day, and then watching the rest of Lynch in short order—renting the tapes, one after another, from the video store attached to the theater, in whose window the movie posters would reappear a year later, when that title came out on video—felt the same. It combined the fear of leaving my comfortable early life with the excitement of stepping into a new one that, crucially, also existed within my town, which served as the site of departure, the land where the curtain hung, and also the land I departed back into when the show was over, vested with all I’d seen and challenged to do the work of equalizing the pressure between one reality and the other enough to live in both. That was therefore the moment I became a writer, determined to do all I could to expand the limits of the world I inhabit and to tease out and magnify the connections among all it contains and seems to conceal. Physically, the American frontier is long closed, but psychically, as Lynch taught me, we have barely begun to explore it.

![]()

Lynch’s protagonists invariably lose the fixity of their prior worldviews by immersing themselves in this exploration, plumbing a darkness that part of them seeks to escape, while another part wriggles deeper in, refusing to resurface no matter what they find. In this way, his films tell loss-of-innocence stories that are also about gaining a new kind of innocence, not the kind that comes from childish ignorance, but the kind that comes from the very adult resolution to look into the abyss and live on anyway, without bitterness or despair. As I understand it, this is the root of mental freedom, which comes from transcending the fear of not knowing, and not wanting to know, who you really are. It’s also the distinction between the childish, which is a failure to grow up, and the childlike, which is a quality that, as adults, artists must retain the ability and courage to access.

It’s a truism about Lynch’s work and personality that he sees light within the darkness, and of course he’s famous for maintaining an almost dopey good cheer in public, grinning like a big kid surrounded by toys, but his love of milkshakes and his awareness of evil are never at odds with one another. His refusal to look away from darkness is inextricable from his refusal to succumb to it. This is why so many of us cherish his films as psychic safety blankets, despite their violence and agony. Unlike the work of, say, Edward Hopper and Alfred Hitchcock—both major influences on Lynch—where the world is cold and desolate and where interpersonal relations, to the degree they occur at all, are based on tricks and transactions, Lynch’s work exudes warmth even at its most grotesque. His films are full of smiles and sunshine, hugs and handshakes, and the moments of torment are always juxtaposed with romance, friendship, and people sincerely communicating their appreciation of being alive. When Kyle MacLachlan muses, “It’s a strange world,” in Blue Velvet, his tone makes it clear that he means this across the full spectrum of experience, from agony to bliss.

![]()

Lynch’s films have been such defining touchstones for my generation (let’s say those born between 1975 and 1995) that I’ve been hesitant to write about them directly, sensing that I could achieve more by working away from their influence. No other artist, in any medium, compares—Lynch is truly the North Star for every American writer and artist I know. There’s something seismic in his work, some way in which he articulates the beauty, horror, humor, longing, and dread of the America we grew up in that is absolutely unavoidable. David Foster Wallace said as much in several essays (seeing Blue Velvet during his MFA years was clearly his own Oz experience, one he describes in the language of religious conversion), and the import of this work has only grown since. If the past few decades have been starved for genuine ideas and meaningful images, stretching on and on into a time of radically fractured ideologies lacking a meaningful center, a world where the old seems denatured even as the new has yet to arrive or even to indicate that it can arrive, Lynch’s work is one of the few places where something eternal and nourishing has cropped up anyway—and, crucially, not despite these conditions but because of them.

Unlike DFW, whose search for sincerity hit a terrible dead end, Lynch found a way to transcend postmodernism and rescue true, even overwhelming, meaning from the ways in which popular culture devolved into commercial shlock as the ’60s moved into the ’80s, and then into disaffection and totalizing irony as the ’80s moved into the ’90s. In My Dinner with André, André Gregory warns that the ’60s represented the last gasp of the true human being, and that as the ’80s got underway, only scattered outposts of humanity would remain, atomized within a brain-dead mainstream. If so, Lynch’s films are foremost among them, miraculously refusing to fight the tide of inauthenticity while also refusing to drown in it.

These films belong to the tiny category of aesthetic experiences—whether of art, drugs, dreams, or pure imagination—that take their place in permanent memory as part of one’s life, inseparable from the core of what makes us who we are. The vast majority of artworks either reflect the world as it already appears to be or present a critical alternative to it; only a handful in a lifetime genuinely become part of it, palpably and permanently altering reality the same way that historical events do. If a writer’s complete body of work amounts to their “inner autobiography,” then the artworks that most influenced that writer are part of this inner autobiography as well: films and books and paintings that I haven’t merely read or seen but that I’ve lived within as much as I’ve lived anywhere else. As my father said while reflecting on the influence Oz had on him, “It not only changed what was in my mind; it changed what I thought of as my mind.”

The joy of Lynch/Oz is understanding how Oz’s influence lives in Lynch in this same way, as that film joins all of his on the underside of American culture, the country within the country, from which meaning sometimes bubbles up to the surface.

The Town within the Town

Blue Velvet, which debuted commercially on September 19, 1986, three days before I was born, remained for years one of the only films that my father forbade me from seeing (“That movie with the wild man in the gas mask and the woman dancing on the car”). When I finally did see it, after all that buildup, it changed my relation to my hometown, and thus to how I’d attempt to render that town in my novels and stories, which have all sought to locate “the town within the town” as their fundamental power source.

The idea that a “real mystery,” as Kyle MacLachlan puts it to Laura Dern, at once too awful to contemplate and too seductive to resist, could take root not only in the dark alleys of Paris and New York but also in my own little backwater, right next door even, was so overpowering that I never thought about myself or where I was from in the same way again. This film proves that we don’t need rarefied materials to touch on the sublime. Much to the contrary, we need to see what’s around us more clearly in order to absorb and reciprocate the signals it’s sending, gleaning something of our own inmost nature in the process. As Rodney Ascher points out in his segment of Lynch/Oz, Blue Velvet’s Lumberton contains both Oz and Kansas, separated by a single street.

This combination of incommensurate elements is part of the great decentralization of America, the Protestant conviction that the most important thing could be anywhere, and that transformation, as William James argues in The Varieties of Religious Experience, perhaps the most American theory of religion ever put forward, occurs unpredictably and unrepeatably, for one person alone. The tornado strikes only when and where it strikes. In other words, nothing has its own place and nothing is neatly sorted—in this country, there are vast wastelands that contain nothing at all and dense points that contain everything at once. In America’s conception of its own mystic potential, the middle of nowhere can be ground zero for historic events—the angel Moroni can appear not in Rome or Jerusalem but in upstate New York—and cosmic reckonings can occur today or tomorrow, not in some hazy revelation hundreds of generations away. In a nation that serves as a new, provisional home for millions who nevertheless still feel estranged in their core, agitated by a sense of having left home never to quite find it again, this decentralization is a crucial aspect of the adventures that Lynch’s protagonists (and viewers) go on, all patterned on Dorothy’s flight away from and then back to Kansas.

![]()

The concept of home as ambiguously situated inside and outside of the self, representing both the need for and the source of shocking transformation, has always been important to my understanding of where art and literature come from, and what they can do. Seen in this way, home is linked to adventure, which may be the only way to find a viable self in the world—“You have to leave to come back home,” as Lynch’s character Jack Dahl advises Louis C.K. on that comedian’s eponymous show, and as MacLachlan learns upon his return to Lumberton at the outset of Blue Velvet. When Dorothy first lands in Oz, she has no clear self and is thus not yet ready to take her place as the protagonist of her own life. Throughout her journey in that otherworld, following the yellow-brick road with the friends she makes, she tries to get home, which is another way of saying she tries to come into her own. To find out who she is, just as, when I write, I hunker down in my room and in my mind in hopes of getting as far from both as I can, so as to thereby understand, upon my return, where I went and what that means about who I am.

Dorothy’s story follows the rules of the adventure genre, wherein the central character is less well defined than the side characters who make up their adventure—think of Alice juxtaposed with the denizens of Wonderland, or Tintin’s blank face compared with everyone else he shares panels with, or Odysseus compared with the monsters he meets, or MacLachlan’s naive cipher compared with the lurid night people played by Dennis Hopper and Isabella Rossellini—because she needs to attain selfhood through that adventure. Side characters like the Tin Man and the Cowardly Lion thus embody the traits that Dorothy has not yet discovered in herself. All she can know beforehand is that she needs to heed the call; she can’t know who she’ll become until after she does. The central thrill of watching Lynch/Oz is to imagine Lynch himself in this state, as a child susceptible to the influence of a movie he’d never seen before, vested with potential he had yet to recognize.

![]()

Oz is “not Kansas anymore,” but it leads to a more meaningful and consequential phase of a life that will have to play out there, as the return home is also key to the adventure. The ambiguity of the phrase “There’s no place like home,” which can mean either that “home” is the best and realest place on earth or that it doesn’t exist anywhere, is central to the film’s function as a rite of passage for so many children just beginning to conceive of themselves as free and multifaceted beings in a dynamic world. The dark but empowering lesson of Oz and Lynch is that you strengthen your ability to live in such a world—to be happy, even, to overcome longing and hauntedness—the more you understand the complexity of otherworlds and non-worlds that surround and infuse whatever you call home, defining its fundamental nature with a core of unknowability that rewards exploration even as it never reveals its secrets. In this apprehension of reality, irreducible strangeness is the crucial component that makes a house, a town, or a nation into a home, one that is worth living in for reasons entirely other than its being safe or comfortable.

Whatever scale we use to define “home,” this uncanny quality of definition through acceptance of the unknowable pertains with equal power. Oz is a place in America, a psychic state you fall into by falling out of the drab open landscape you’d inhabited before, while also falling deeper in, into an inner chamber that’s also a pure elsewhere, not the inside of anything, like the Red Room in Twin Peaks, a place that, even in its extreme artificiality, doesn’t seem to have evolved or even to have been built, but one that’s always been waiting, perhaps for Agent Cooper alone.

![]()

Like the Red Room, Oz combines the natural (or at least the emergent) with the extremely artificial—everything there looks handmade, yet it also feels like it’s always been what it is, a landscape as complete unto itself as any other.

By building a world composed of such spaces, Lynch showed my generation a way through postmodernism and into a new outlook that’s no longer concerned with sorting the real from the fake, the event from the representation, the sincere from the ironic, or even the cause from the effect. Working in a vein that transcends satire without returning to earnestness, Lynch fuses both modes into a single rich plane of possibility, redefining what it means for events to “happen” through a much more sophisticated, and ancient, understanding of dreams and imagination as arenas for real occurrences, not as a reprieve from or representation of them. Our waking life is built upon our dreams just as much as our dreams reflect our waking life, and in neither case is interpretation the key—rather, in both, the key is total openness to whatever actually exists.

In Lynch’s world, the most common substances—coffee, cherry pie, PBR—become totemic versions of themselves without losing their endearing banality. They don’t stand for something more important, as they might in the work of a doctrinaire surrealist; rather, Lynch reveals the importance they’ve always had, something intrinsic to their nature rather than extrapolated from it, just as he takes his own greatest influence from Oz, one of America’s best-known artifacts, not from rarefied sources known only to trained artists. Object and metaphor are inseparable for him because, as in a dream, the depth of meaning that everything contains is laid bare on the surface, which is why attempts to explicate his films always fail—his films are experiences to enjoy, not messages to decode. As DFW put it, comparing Reservoir Dogs to Blue Velvet, “Quentin Tarantino is interested in watching someone’s ear getting cut off. David Lynch is interested in the ear.” An ear, I would add, that is both rich in association with the subterranean, insect-infested world MacLachlan descends into in order to become a man—a descent into the town within the town—and also, truly, just an ear.

American Carnival and Bottomlessness

This method of drawing meaning out of common objects without overlooking their commonness also emanates from Oz, a land whose strangeness grows out of what is already true about Dorothy’s life, adding nothing to it but revealing a dimension she’d previously been unable to see, just as the onscreen spectacle coheres into something otherworldly even while emerging from the pedestrian materials of 1930s studio stagecraft and the economics that made it possible. No stranger to the mythos of the carnival—after all, he made his own debut into the studio system with 1980’s The Elephant Man—Lynch understands better than most how the questions of surface vs. depth and mask vs. face are not unique to the postmodernism of his time. Indeed, as the circus and carnival demonstrate, the authentic American mythology has always been that of the inauthentic—the Wizard isn’t really a wizard, but the moment of his unmasking is an authentically mythic moment, as canonical and moving as any we have. Well before the twentieth century, P. T. Barnum built a circus empire on the knowledge that Americans sincerely enjoy participating in their own deception.

America is at its most psychologically invigorating when it embraces this apparent contradiction, admitting its own nature as a land of geographic and psycho-geographic uncertainty, of weird troughs and caverns you can fall into alone, with no one to tell you if you’ve left America or found it at last. As so many of us have, or claim to have, gone on these journeys here, we’ve established a culture of hucksters, big talkers, and charlatans—that which Charles Portis evokes so richly—built on scams, boasts, and fishy religious visions. This comes at a price, as the flipside is a legacy of predation, subjugation, and disappointment, but the feeling of narrative churn, of the weird, the beautiful, the comic, and the freakish constantly arising from an open wound, and of there being no master narrative to stanch it except that of an “American dream” whose dreaminess is absolute, still imbues the culture with the unique capacity to produce what we now understand as the Lynchian.

Oz is one such emanation from the wound. It’s sui generis, not part of any tradition—there’s no preexisting relation between this place and the culture it underlies; Dorothy has never heard of it, nor has anyone in the micro-society she inhabits. She is in this sense a kind of American saint, one who has a vision that bolsters her from within rather than bolstering the edifice of any preexisting religion. Oz either comes into being at the exact moment her house lands there, or else it’s older than known history, eternal even, revealing how flimsy the foundations of her life in Kansas had been, as they were for all the homesteaders who set out for that part of the country in the nineteenth century. This is unlike the Black Forest in a Grimm tale or the shores of the Mediterranean, real locations suffused with thousands of years of mythology building upon itself into a durable edifice. The lack of any such edifice, or the feeling that it exists without anyone’s knowledge, is the essence of the American imaginary. Unlike Europe, which is old in a measurable sense, America is both brand new and ancient, as in a Western, where the landscape is prehistoric yet the events occurring upon it are contemporary, as potent as the Greek epics or Norse sagas but occurring in real time, before the eyes of whoever happens to be there and then again in the stories they choose to tell.

The beauty of America is thus that the source code is open—it’s no coincidence that the internet originated here—but the horror, by the same logic, is that there’s no solid bottom to land on. You can plunge right into the myth layer but also collapse through it, into nothingness. There’s no congealed tradition at the very bottom to stand on if you fall too far, no safety net, not just financially but spiritually as well. You might see aliens or Bigfoot in your backyard—or Munchkins and talking scarecrows—and you might find others who claim to have seen the same thing, and others still who deny that it’s possible, but at the end of the day, in this country, everyone faces the unknowable alone.

This is a level of horror that Lynch accesses often—picture Bill Pullman’s shrieking face at the end of Lost Highway, which Greil Marcus terms “the American Berserk,” or the raw presence of Bob in Twin Peaks—and also a level of boundless possibility, a manifestation of the “ocean of pure, vibrant consciousness” that, from his perch as a meditation spokesman, Lynch extols as the truth of all interiority (as well as “the source of all matter”). It’s a space beneath archetypes, deeper than Jung’s collective unconscious, one that infuses Oz with its enduring power—the degree to which it doesn’t make sense and can’t be “solved,” forcing Dorothy to metabolize her own experience, integrating it imperfectly into whatever life she goes on to lead.

In the process of writing a paper on Vertigo, Persona, and Lost Highway in college, I came across an essay on Lynch that made a crucial point about the role of fantasy in his work. It argued that fantasy can never solve problems within reality, but it can clarify their hidden nature, as in Lost Highway where at first Pullman fears his wife is cheating on him and then he breaks through to another realm where he and she both become different people, engaged in an affair that is both betrayal and reunion at once. In the fantasy realm, you aren’t vaguely divided unto yourself—you’re literally two different people. The problem remains, and perhaps even intensifies, but it’s impossible to remain confused or in denial about it. Lynch’s insight into the nature of this mechanism surely also comes from Oz, where all the people in Dorothy’s Kansas life are reincarnated in hyper-clear form: for example, the mean woman who wants to kill Toto becomes the Wicked Witch, while Professor Marvel, the shabby psychic Dorothy meets in a circus wagon outside of town, becomes the Wizard. This doesn’t solve her problems, but it lets her see them with the clarity that only pageants and rituals can achieve, just as masks serve both to hide a person’s face and to display their otherwise-hidden essence. Clown paint obscures our individuality just as our apparent individuality obscures our inner clown.

This is the source of the strange beauty that still emanates from this country. It’s a beauty whose nature never becomes explicit, with origins that can’t be traced, a just there quality to towns, bars, and vistas—and their carnivalesque inhabitants—that’s both familiar and unrecognizable, a blend of the solipsism of a young culture still trying to get its story straight and the fascination and fear of a country so large and decentralized that there’s never any knowing who else is out there, and what they believe and intend, a country of cults, conspiracies, and secret compounds that may have no common culture at all. The possibility of stumbling into Oz, with all its wonder and horror, is barely metaphorical—it’s a barely heightened version of what might await anyone taking an unfamiliar exit off any lost highway in any state.

Rolling into any such place, everything could have been there forever or set up yesterday, and it could all be gone tomorrow. Where did Blue Velvet’s Frank Booth come from? (For that matter, where did Dennis Hopper come from?) Why is he in town? What about his friends, like the guy who sings so tenderly into the lightbulb in the middle of the night? They’re just there, waiting for Jeffrey to meet them, to show him something about adulthood, about sex, drugs, and violence, about the spaces you can wander into, always nearer than you imagine, when you leave what used to be your home or mature to the point where you realize it never was.

![]()

The idea of a midnight show—the essential space in all of Lynch’s work, one he returns to in nearly every project—that you stumble into by accident and yet come to feel was put on for you alone also stems from Oz. Dorothy is a stranger in this meticulously crafted land where everyone is playing what seem like eternal roles, and yet for whose sake if not hers are they playing them? Here, the essential oneiric nature of cinema is made manifest, the dissolution of barrier between the position of being a voyeur of a spectacle you’re not supposed to see (Jeffrey peering through the closet while Frank Booth assaults Dorothy Vallens) and the knowledge that there would be no spectacle if you hadn’t paid to see it.

This is the feeling the women experience in Mulholland Dr. when they enter the Silencio nightclub, and that my friend and I experienced when we entered Mulholland Dr., a memory I now gladly conflate with this scene in the movie, which has become the core Lynchian image, his midnight show of shows, as emblematic of his aesthetic as Nighthawks is of Hopper’s. Watts and Harring are complete strangers at this show, and yet here, too, it seems to be just for them. Indeed, it seems as though they’re part of it, playing their roles along with the figures onstage. This is obviously true on the level of the film itself insofar as everyone onscreen is performing for the viewer, but it also feels true in the film, like the women know they’re performing in a makeshift carnival even as they’re having a transformative experience as visitors to it. This is the American duality, the feeling that we are at once making it up as we go, trying to find purchase in a place where we don’t belong, while also falling into a pattern, perhaps one etched by forces from another dimension.

Ours is a wildly individualistic culture, one in which everyone is the hero of their own perilous journey and God of their own improvised religion—a dream in which the dreamer is equally the subject and the environment the subject moves through—and yet, in the well-worn grooves of this narrative, we all play our part, acting out individuality in a perversely collective manner, just as both women are shocked by the spectacle they witness at Silencio even though they appear to have roles within it, and just as Watts’s attempt to become a star in Hollywood is both her own intimate vision quest and the oldest story in the book.

![]()

Now that Americans have traced these patterns for several centuries, an undercurrent of boredom, even ridiculousness, flows through the narrative of heroic self-determination. The carnivalesque here has become increasingly juxtaposed against the crushing sameness of daily life, the exhausted quality of the twenty-first century so far, that of a frontier culture struggling to adapt to a post-frontier reality. One theory of Oz that Lynch/Oz explores is that the film is a piece of anti-frontier messaging, telling Americans even in the 1930s to tamp down their pioneering spirit and learn to be happy staying put. It is, one could argue, an advertisement for vacation (and of course for cinema) as the new mode of transformative travel.

Whether or not you see the film in this light, Lynch and Oz both clearly play with the delicate balance between the desire to forsake the normalizing comforts of home and the desire to cling to them, to see the normal as normal and never question it, either because you know the horrors that lie beneath, or, even more disturbingly, because you know that nothing does. This is another fundamental American anxiety: Did we flee the Old World in order to invent something radically new, or only to recreate it in degraded fashion because we grew afraid that nothing else was real? Dorothy embodies the can-do American spirit of accepting that Oz is nowhere she’s ever been before and thus must be navigated solely through common sense and self-reliance, but she’s unable to remain there for longer than it takes to get home.

After the Silencio show, when the women break into real tears upon being told there is no band and watching a woman lip-sync a Spanish song whose main lyric is “I’m crying,” they return to their drab Hollywood bungalow and engage in a sex scene that is at once an overwhelming, ecstatic communion and also a humdrum piece of softcore porn, no more unique than the TV detective beats that inform so much of Twin Peaks.

When the circus comes to town, its meaning derives from this clash between the heightened and the banal, the unique and the cliched. If the town had already actualized its own bizarreness, rather than smothered it in denial, the circus—and the movies—would not be necessary. At the same time, if the circus allowed itself to grow so bizarre that it failed to function as a business—if it couldn’t commit to the banal realities of running a show—then it would be unable to turn up at all. So these two forces are always entwined, both in the practical realities of show business and in the stories that Oz and Lynch choose to tell. In my own hometown, the experience of seeing Mulholland Dr. that afternoon derived its power from a combination of geographical seamlessness—the theater was right there, across from the Chinese restaurant and the nail salon, not in some derelict outskirt we’d never seen before—and tonal disjunct—nothing we’d ever experienced hit the notes that movie did, and yet somehow the town contained it with ease. We could reemerge at dusk and go home to dinner and pack our binders for school in the morning and . . . get on with our lives, despite having been changed to a degree that rendered this continuity absurd.

The Kansas-California Axis

When I picture how cinematic images reach and help define our homes, I picture the American imagination rolling like a tumbleweed across the plains and desert until it ends up on the West Coast, at which point it has no choice but to turn back east and filter all it has seen into a dream. Economically as well as imaginatively, Kansas and California are locked in symbiosis, as the dreams are put on film in California but only turn a profit if they play in Kansas, if by “Kansas” we mean both the specific state and the whole vast interior of the country, whose geographical center is indeed embedded in the Kansan plains and where much of my fiction over the past ten years has been set (my in-laws are deeply rooted there).

The Kansas-California axis also characterizes Lynch’s personality and life project, both within stories like Mulholland Dr., where the small-town girl goes to the City of Angels to seek her fortune, and Twin Peaks, where the big-city agent goes to the small town to discover what lurks beneath the logs of the rural psyche, and in the origin story of Lynch himself, that of a genuine midwestern outsider who took his dreams to Hollywood and, instead of being crushed by the machine, staked out a durable place within it, doubling down on his kinks and quirks even as he became a global celebrity. As a public figure, Lynch therefore embodies two of our most definitive archetypes—the sincere, plainspoken, hard-working homesteader (he grew up in Idaho and Montana, but much of the accent and affect, which he clearly plays up, is similar to what you find in Kansas, or in the Minnesota of Judy Garland’s birth), coupled with the urbane, ambitious, half-sincere and half-duplicitous seekers who flock to California to become larger than life. I can think of no other public figure who is both so unreachably famous and so doggedly down-home, and in whom those two aspects do not clash, as they did in the figure of Judy Garland.

The tragedy of Garland’s offscreen life is part of the fascination that’s traveled through time attached to her performance in The Wizard of Oz, itself a product of California’s attempt to, as it were, present Kansas back to itself. As Lynch/Oz explores in depth, the fact of Garland as a tormented cultural icon bound for disaster is inextricable from Dorothy’s rugged innocence and unflappability. By the time she took her best-known role, Garland had already seen the depravity of Hollywood and yet she sublimated it into a character whom no darkness could overwhelm. Knowing that Garland would succumb to the demons that Dorothy vanquishes imbues her performance with a gravity that is impossible to overlook.

From the point of view of Kansas, “somewhere over the rainbow” is California, but from the point of view of California, where Garland is actually singing it, bursting with the longing to escape, it’s . . . what? Another, deeper, truer California? Where? I’ve always felt squirrely in that state, especially in Los Angeles, which gives me a crawling-up-the-walls feeling that I think comes from there being nowhere left to go, no frontier left to explore, no further reinvention to avail yourself of. The rest of the country has California in its back pocket, an inbuilt Plan B, a last chance for a fresh start, but in California itself, there is only fantasy, whether one accesses it through film, money, cults, technology, or psychedelic drugs—the major, and not mutually exclusive, Californian cultural vectors of the last century.

Indeed, the connection between Oz, the psychedelic movement, and Lynch is tied to the mythos of that state at the point where its status as the end of the frontier meets its unstoppable search for new ones. The evergreen stoner game of watching Oz while playing Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon is surely the most famous point at which that film intersects with psychedelia, but the intrigue doesn’t end there. In Lynch/Oz, David Lowery (director of the astounding A Ghost Story) discusses his teenage obsession with the legends surrounding the film’s production, from the Munchkin actors’ debauched behavior in the hotel they were staying at, to the rumor that a dead body could be seen in the background of one shot, and much more. What’s clear is that Lynch isn’t alone in perceiving something unique emanating from this film, not only from the story it tells or from the images it presents, but from the object itself and the facts of its production (how could Victor Fleming, hardly a household name, have directed this and Gone with the Wind in the same year?).

This aspect of Lynch/Oz speaks to a fluidity between on-set and onscreen reality that recurs in many Lynch films and that pervades the entire mythos of Hollywood, where the camera exists in a fraught, multidimensional space, not as a clear demarcation point between the real and the pretend. Oz may not be a real place (or a real wizard), but The Wizard of Oz is a real thing, and not just as a children’s movie—there’s something about it that both emerges from and extends into our world to infect all who behold it, like the cursed titular tape in DFW’s Infinite Jest.

The occult involutions of the filmmaking process also play major roles in Mulholland Dr. and Inland Empire, and a more subtle role in Lost Highway (think of the Mystery Man with the camcorder to his eye in the burning desert cabin near the end). Epitomized by the image of the tiny director in his ominous command center in Mulholland Dr. (surely a reference to the Wizard at his console), this is another facet of Lynch’s influence on my generation, since we’ve seen the relationship between what a piece of media is, what it claims to represent, and how it came into being grow ever more complex, heading toward a point of derangement that may have already come and gone.

![]()

Along with Thomas Pynchon and Bob Dylan, both of whom also spent formative time in California, Lynch is one of the few artists working today who salvaged something genuinely useful from the ’60s counterculture and kept it alive throughout the ’80s, when so much of hippiedom was decaying into yuppiedom. For me—born in that ’80s aftermath, with the ’60s as a beautiful dream dimming in the eyes of the adults around me—the doors of perception opened as a teenager with a combination of psychedelics and Philip K. Dick, Hunter S. Thompson, and Robert Anton Wilson books, but what resonated most was Lynch’s ability to draw wonder and horror together with the idea that neither could spoil or redeem the other. It wasn’t that a good trip had turned bad, or that another good trip could save us from the bad one that had returned in the Cold War’s eerie aftermath, but rather that a place beyond conventional morality—a place like Oz or the California that serves as America’s ultimate fantasy of itself, a place you both long to escape to and escape from—existed, and that the real morality of the artist is to visit this place as often as possible, disavowing any maps that don’t include it.

Looking back from today’s vantage point on the Boomers—America’s largest and in many ways luckiest generation, and now its most popularly reviled, who made the ’60s what it was—the question seems to be whether they were living a dream that turned into a nightmare, their idyllic Blue Velvet townscapes ruined by ravening madmen in the night, or if what was already the case, festering underground, simply refused to yield. Roy Orbison’s voice, one of the bedrocks of Lynch’s sonic world, evokes this feeling of the ’50s persisting into the ’60s and beyond as well as anything can. There was a loss of innocence for that generation—Manson and all the assassinations and Vietnam and Watergate, etc.—that my generation was born into, a given from square one. This is another part of why coming of age with Lynch was so important, as he filtered this American fall from grace through a lens that felt generative of new ideas, not only purgative of old ones. There was no sugarcoating the nation’s rotten essence, but neither was there any despair in confronting it.

Both Sides of the Curtain

The Wizard of Oz was released in 1939, on the eve of the war that would claim more lives than any before it and birth the era in which, over the course of Lynch’s life, America became the supreme world superpower, rising to dominance and falling from grace. Today, that rise and fall arc feels quaint. It feels like we’re beyond that rainbow for good. Perhaps this is not the true end of America, or even the end of its world hegemony, but it’s definitely the end of a certain mood, and the beginning of an inversion, one in which the underside has come out on top. America today is not the hokey Kansas-by-way-of-California that Dorothy starts out in, or the blinding green lawns, red roses, and white fences that open Blue Velvet, but rather the freak show that all of Lynch’s characters end up in once they peel back the curtain. The wild man with the gas mask and the woman dancing on the car are not dead-of-night phenomena anymore: they’re all around us, rampaging in broad daylight.

If there is no longer any innocence to fall from, what remains of America is the pure crystallization of this carnival, the creature behind Winkie’s diner sitting one booth over from the rest of us, stirring sugar packets into cups of coffee, such that there are no more curtains or tornadoes or other interventions necessary to mediate between home and away, or any Pleasant St. Theater to duck into on a Sunday afternoon. This marks the onset of a new age, one that Lynch has prepared us for but that we must explore further alone. When I told my father, in many ways a personal surrogate for Lynch—both were born in the ’40s and went to art school in Philadelphia in the ’70s, both are sculptors, among other occupations, both have unruly gray hair, and, most importantly, both are animated by a sage-like eccentricity that balances a deep awareness of the rot lurking in the human soul with an iron-clad commitment to living in wonderment nonetheless—that I was working on this piece, he said, “I’ve been scared of those monkeys all my life.” A moment later, he added, “And I’ve been running from them all my life.” Maybe we all have. If so, then the question is where have we run to? What is the fate of the American imagination, if, as I hope, we haven’t reached the end of its yellow-brick road?

When Dorothy returns from her adventure, she’s been changed by Oz and by the knowledge that home exists on both its near and its far side. The familiar is in a continuum with the bizarre, the cozy and the harrowing nearly indistinguishable from one another—this is the knowledge that Oz leaves her with. The film ends here (a discussion of the many traumas of 1985’s Return to Oz will have to wait), depositing her on the cusp of maturity, just as I emerged from Mulholland Dr. having undergone a profound growth experience, the seeds of all the stories I would go on to write already stirring inside me, and my understanding of the potential within the pedestrian materials of this world—ink, paper, makeup, costumes, music, celluloid, towns—wildly expanded. The greatest art does this: it dissolves the opposition between one side of the curtain and the other by proving that both sides exist in the same world and that exploring both at once is the artist’s supreme task, one that can make an entire lifetime worthwhile.

This is the experience I most want for my daughter, when the time is right. It probably won’t be Mulholland Dr. that does it—for the sake of art’s future, I hope it’s something that doesn’t exist yet—but, one way or another, that illumination, the feeling that life isn’t boring, or that even the boring is fantastical and strange, that one’s days and years aren’t a holding pattern from which to seek reprieve, is the gift of a genuinely visionary experience because it redeems all moments, suffusing them all with possibility, not only those rare occasions when the circus comes to town. Today, the wound in America remains open, spitting up freaks and weirdos at an accelerating rate. There may be suffering attached to this fact, but Lynch’s legacy is to show that there is unbounded joy as well. The American dream of finding a stable, safe, sane home in this land may be a vicious delusion, but the American dream as dream has never been more charged with potential. It’s easy to look back and mourn what’s ended, or what never was, but the path of adventure is to plunge onward anyway, willing to be broken down and remade by whatever lurks in the places we have still failed to explore. If ever you sense a midnight show is starting up in a theater you can just barely imagine, you owe it to yourself to go there and take a seat in the dark. ![]()

David Leo Rice is the author of several novels, including The New House, Angel House, the Dodge City trilogy, and The Berlin Wall, forthcoming in 2024, as well as the story collection Drifter, named one of the “10 Must-Read Books of 2021” by Southwest Review. His next collection, The Squimbop Condition, will also be out in 2024.