The title of José Donoso’s The Obscene Bird of Night comes from a letter Henry James Sr. wrote to his sons Henry and William:

Every man who has reached even his intellectual teens begins to suspect that life is no farce; that it is not genteel comedy even; that it flowers and fructifies on the contrary out of the profoundest tragic depths of the essential dearth in which its subject’s roots are plunged. The natural inheritance of everyone who is capable of spiritual life is an unsubdued forest where the wolf howls and the obscene bird of night chatters.

This beautiful, baroque, vaguely terrifying passage offers an oblique map of the novel’s conceptual territory. As Donoso expands and explodes the legend of the imbunche—a Chilean folkloric monster—the dissolving figure of the protagonist, writer manqué Humberto Peñaloza, unleashes a phantasmagoric overlap of scenes, memories, fantasies, and dreams. The “genteel comedy” of aristocratic life exists on the remote estate of La Rinconada, one of the novel’s settings, but only as an alterity, a void around which Donoso constellates his kinetic fragments. The novel’s “unsubdued forest”—an extraordinary variance of narrative, tone, and psychedelic matter—overflows with ouroboric obsessions, unexpected exchanges, role reversals, inversions, intimations, false starts, decaying myths, unlikely rumors, and secrets that elude intelligibility. It is chillingly communal in its vision of the human capacity for monstrosity, vengeance, and cruelty—“the natural inheritance of everyone who is capable of spiritual life”—a madness transmitted by individuals, families, societies, and countries alike. And running beneath it all is a subterranean void—“the essential dearth”—circumscribing the possibility of health, peace, and reason: call it modernity, disenchantment, exploitation, or a curse brought on by the witch Peta Ponce. Such bottomlessness thrills and terrifies. It insists on the illusion of the perceived world, a nothingness dressed in the rags of appearance.

José Donoso was born into a family of doctors and lawyers—purveyors of arguments, cures, and (one presumes) no small amount of “genteel comedy”—in Santiago, Chile, in 1924. He studied English literature at the University of Santiago, eventually finding his way to Dickens, Faulkner, Woolf, and Sterne, Proust and Dinesen, Kafka and Sartre. Despite his voracious appetite for international literature, he maintained it was his parents and their servants who had the greatest influence upon him as a writer. It shows in the devoted, testing, mock-deferential language of his characters, often of different stations, an upstairs-downstairs dialectic of philosopher servants, assistants doubling as holy fools, and the lost or compromised rich, their shared idiom one of half-truth, tradition, misunderstanding, back talk, and humiliation. He maintained a peripatetic life, living and teaching in Buenos Aires, London, and Barcelona alongside frequent sojourns to the United States, including stints at the University of Iowa and Dartmouth. The author of eleven novels, he is best remembered today as a major figure of the Boom, the aesthetic and commercial flowering that turned Latin American writers like Julio Cortázar, Carlos Fuentes, and Gabriel García Márquez into household names. He died of liver cancer in 1996.

Myths have sprung up like mushrooms around his masterpiece, The Obscene Bird of Night (1970). The novel’s convoluted genesis trails it like sensational plumage. The mythologizing began with Donoso himself: “I didn’t write this novel,” he claimed, “the novel wrote me.” It was a difficult, even mortally perilous project. Donoso labored over the novel for nearly eight years across two continents. Though he set out to write something “very simple, very clear,” what emerged instead was gnarled, monstrous, dreamlike, obscene. Its composition nearly consumed him. Driven by financial need, he returned to the United States, to Fort Collins, Colorado, to teach for a semester. There he was beset by the bleeding ulcer that had plagued him for years. After an emergency surgery, he was given morphine, unaware he was allergic to it. “I had an incredible fit of madness, with hallucinations, paranoia, and above all a terror that was larger than life,” he said of the experience. “Every pain, every humiliation, every affront, exploded into something huge. It was schizophrenia. Politics, sex, buried racial prejudices, all those elements took on another life in those hallucinations . . . a larger life.” According to Donoso, the novel’s structure emerged from this narcotic fog. Utter derangement was a prerequisite for its completion.

It has awaited its global moment for decades, slowly accreting readers, reviews, rumors, and, more recently, galley brags and breathless tweets. A veritable who’s who of contemporary Latin American literary stars have stamped Donoso and his work with their imprimatur. There is Roberto Bolaño: “To say he’s the best Chilean novelist of the century is to insult him. I don’t think Donoso had such paltry ambitions.” (He also called The Obscene Bird of Night “ambitious and uneven,” a charge sometimes levied against his own baggy, energetic masterpieces.) Or Fernanda Melchor: “José Donoso is my favorite author of the Latin American boom (better than Gabriel García Márquez).” Or Alejandro Zambra: “The magisterial and meticulous and excessive representation of failure is, of course, the most radical triumph, the novel’s greatest triumph.” Neither a purveyor of magical realism nor a spun-floss formalist, Donoso represents a darker, more mysterious dimension of Latin American fiction, a writer of metaphysically gothic novels marbled with philosophy, oral history, class consciousness, and psychological horror.

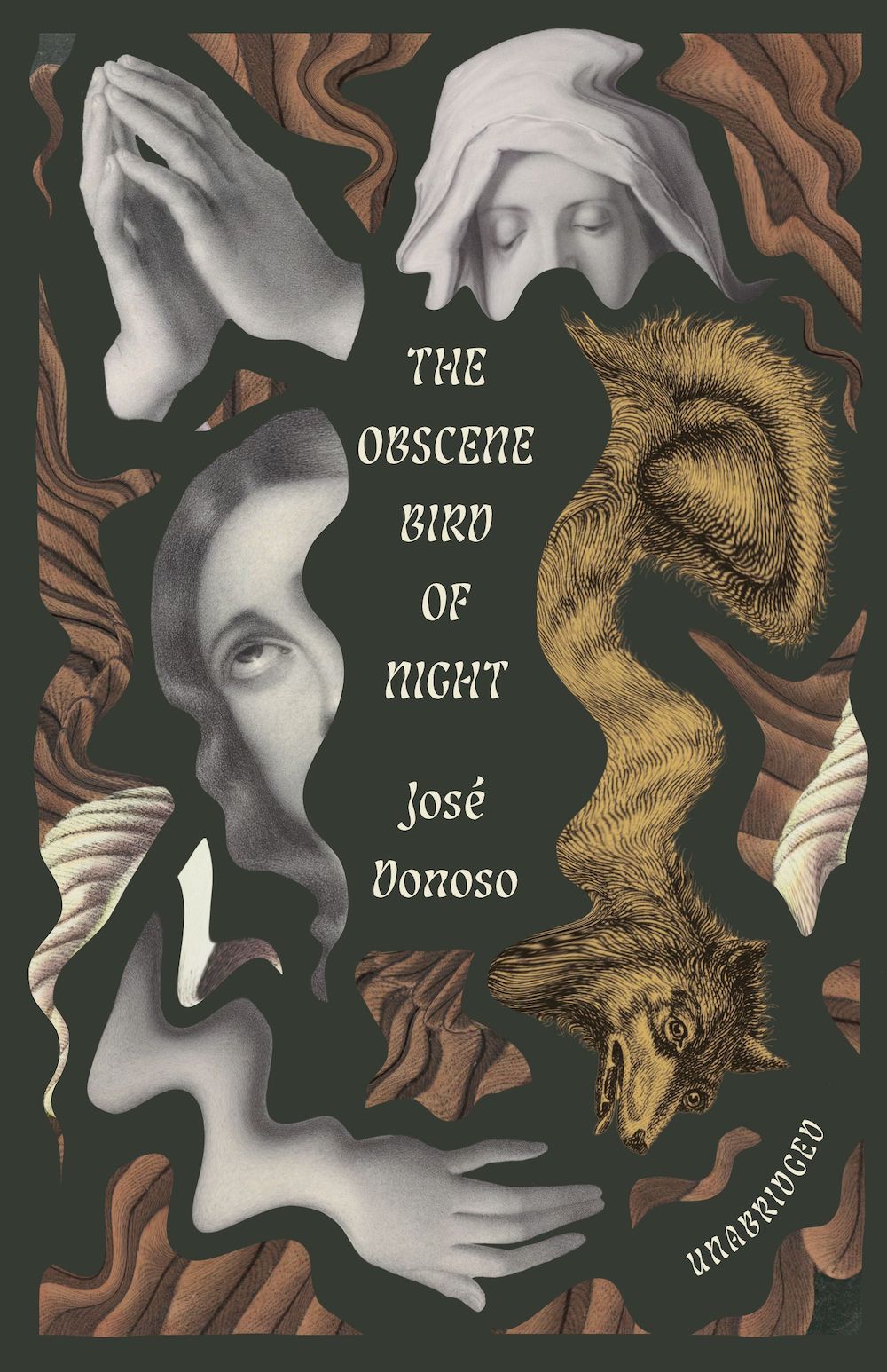

It seems a ripe moment, then, for The Obscene Bird of Night to graduate from its cult classic status. (It is, after all, a work born to absorb, hibernate, and rematerialize elsewhere.) New Directions has published a new, unabridged edition in a revised translation from Megan McDowell, including nearly twenty pages of previously omitted material. (McDowell worked from an earlier translation by Hardie St. Martin and Leonard Mades.) The novel’s introduction, written by Zambra, takes inventory of its themes: “Abnormality, sterility, illness, deformity, inheritance, exploitation, obsession, senescence, madness, paranoia, paternalism, parochialism, isolation.” It is a fine list, and accurate as far as it goes, but what is most remarkable about the novel is its ability to evade the snares of description and summation alike, to remain a cloudy plasma beneath its nightmarish carapace. Orienting categories slide from its surface. Personal, political, or cultural uses are summarily rejected. It will not serve as a tool of education, nor will it provide anything like moral instruction. It is far too large, too strange, too catastrophically different to be rendered useful in any sense. After spending weeks with this teeming, magnificent novel—one of the great reading experiences of my life—I can only repeat what one of its characters says of the plausibly infinite Casa, that it is “a photographic negative . . . of the whole world.”

Donoso conjures a flexible, fluid narrator to navigate the vastness of his novel, a figure at home among aristocrats and servants, dreams and realities, pasts and presents, witches and saints, perfections and monstrosities. Humberto Peñaloza, also known as Mudito or “little mute,” revels in this ambiguity, a savvy tactician from the seat of his own marginality. He inhabits the endless courtyards, rooms, hallways, chambers, and attics of La Casa de Ejercicios Espirituales de Encarnación, a foreclosed, decaying convent in a nameless Latin American city that acts as a kind of philanthropic retreat house for old women and a handful of orphans, a place “that breeds time, time that does not flow but stagnates among adobe walls that will never fully fall.” He is no less at home at La Rinconada, the estate of the senator Jerónimo de Azcoitía, for whom Mudito acts as secretary and valet. A hero of multiplicity, Mudito developed his elastic aptitude in response to the challenges of a complex, layered world: “Today I’m myself and tomorrow no one can find me, not even I myself, because you’re what you are only for as long as the disguise lasts.” He pities those like Mother Benita, the head nun, who are held “prisoner in a single identity.” For Mudito, unity is illness, or weakness, even as he descends into a kind of time-psychosis, a persistent overlapping of discarded selves.

His sole mission is to preserve a way of life suddenly under threat. At the novel’s outset, the convent faces demolition, its chapel set to be deconsecrated. Its only champion is Inés, the disgruntled wife of Jerónimo de Azcoitía, who has absconded to Europe to petition the Vatican. House Azcoitía faces its own kind of destruction, Inés having produced no heir. (Her crone of a handmaiden, Peta Ponce, may have altered her womb. Witches are everywhere in the novel, procurers of poisons, voracious sex addicts, animal skinwalkers, masters of fate.) Mudito boards up windows and walls off passageways, ostensibly to prepare for the convent’s leveling, though in truth to prepare hidden places where he and the others may yet live on, unaccounted for, in the labyrinthine courtyards of the Casa.

Mudito’s masterplan centers on Iris, a half-witted orphan who resides in the Casa and spends her days performing provocative dances for the local boys and “playing yumyum” with the Giant, her lazy, scheming, and much older boyfriend. The Giant wears a massive papier-mâché head while handing out fliers for a mattress store, a lurid costume that seems to drive Iris wild. Mudito strikes a bargain for the prop, which he uses to disguise himself and impregnate the oblivious Iris in an abandoned car. He then rents the head out to various boys, businessmen, and politicians in the city, including his master, the sexually luckless Jerónimo de Azcoitía. “I won’t have trouble persuading Don Jerónimo that my son, who will be born of Iris Mateluna’s womb, is his, the last Azcoitía,” Mudito says. “He’ll become the owner of the Casa. He’ll keep it from being destroyed and it will go on as now, a labyrinth of solitary, decaying walls within which I’ll be able to remain forever.” The nuns deem Iris’s pregnancy a miraculous conception and await the child’s birth for the remainder of the novel, pinning their hopes on the infant that will surely save the convent from destruction.

Mudito’s strategic gambit is the novel’s engine. Donoso uses it as a digressive invitation, an unfurling of the novel’s pocket histories, obstructions, demurrals, and legends. Each tale—a journey into the interior of a self, an era, or an aberration—is deeply connected to the life of the Casa, the Azcoitías, or Mudito himself. The result is a calamitous palimpsest. We discover, for instance, the origin of the Casa in a story shared by one of the old women housed within the convent. It seems Inés de Azcoitía—ancestor of the present-day Jerónimo’s wife—practiced witchcraft alongside her decrepit nursemaid. (Their supposed crimes ranged from inflicting famine to animal shapeshifting.) The girl’s father, a wealthy farmer, has the young woman cloistered in a labyrinthine convent specially built for her. Thus is the Casa born from duplicitousness and confusion, a consequence of occult transgression—unless it was all simply a misunderstanding. For as it happens, a different legend also holds sway at the convent, that the girl was not in fact a witch, but rather a saint who once heroically held up the walls of the Casa during a great earthquake. The orphans never tire of hearing these stories, as if “waiting for the final synthesis” of the two conflicting tales. Mudito, aware of how lies metastasize into legends, is unconvinced by either version: “I’m sure something very simple happened,” he reasons.

Donoso, too, seems to be working toward some grand, ravishing “final synthesis” over the course of the novel. That the young woman—witch or saint, or possibly both—has the same name as the contemporary Inés is suggestive of the book’s habit of juxtaposing twinned persons or events, warring inversions that rub against one another, throwing off sparks. As these uncanny doubles and contradictory scenes proliferate, we have the growing sense of a secret shadow world, one rife with doppelgängers and alternate histories. The reader becomes attuned to these pairings over time, locating linkages with paranoiac glee. There is the original (unnamed) handmaiden-crone of the girl-saint and the contemporary witch-servant of Inés, Peta Ponce; Iris Mateluna is impregnated by Mudito, or Jerónimo de Azcoitía, or neither; Mudito is either a deaf-mute who has always lived at the Casa or he is a writer, Humberto Peñaloza, with a unique and verifiable history; servants shapeshift into “the yellow bitch” to stalk the land, while Inés later chooses “the yellow bitch” to gamble with the convent women in a dog race parlor game; the present-day Inés gives birth to a monster, Boy, who remains hidden away in La Rinconada, just as Iris eventually gives birth to a child, also named Boy, who remains cloistered at the Casa. And so on (and on and on). Reality is described, pulled inside out, and described again, the events hanging from the same armature but inverted, reversed, or otherwise askew. Revelations pitted against one another become rival actualities, two versions of one event trembling in the tension of a dialectic.

Monstrosity, perhaps Donoso’s great subject, is part and parcel of this mirrorlike formalism. He is the laureate of grotesque paradigms: everything freakish, everything hideous, everything gruesome, everything sterile, everything cold or clammy, fishlike or harelipped, too large or too small finds its way into the novel. He uses the dreadful power of the monstrous to mock and make filthy the world of the beautiful aristocrats, the Jerónimos and the Inéses, whose own lives are marred by the unredeemable monstrosity they discover within and without. Grotesquerie is here its own kind of nobility, at odds with the status conferred by family or wealth, a physical stamp that enables a perfect—and perfectly wretched—freedom. “Ugliness is one thing,” Mudito believes. “But monstrosity is something else again, something of a significance that was equal but antithetical to the significance of beauty.”

Nowhere is this paean to the “sick, deformed, laughable, and erroneous” more forcefully depicted than in the monster menagerie of La Rinconada, where grotesquerie is “exacerbated to the sublime.” When Jerónimo de Azcoitía sees the son Inés has finally given him—a monstrous boy with a humped back and twisted legs, the possible issue of a darkly farcical sex trap enacted upon Mudito by Peta Ponce—he decides to spare his son a life of torment by turning the estate into a private society populated entirely by freaks and monsters, such that “the normal world would be relegated to the faraway and eventually disappear.” The child, who goes by Boy, is given a life of ease and plenty, with access to the estate’s rolling grounds, swimming pools, and putting greens, as well as any female monster he desires. He knows nothing of the outside world and has no conception of death, disease, or deformity. The private society is administered by Mudito, as Humberto Peñaloza, and Emperatriz, an ambitious dwarf and possible cousin of Jerónimo.

The grotesque paradise, though, cannot last. Power struggles, overcrowding, administrative incompetence, and desertion erode the utopian dream. Over time the monsters stratify into classes—“first-class monsters” being those afflicted by the most hideous defects, the “second-class monsters” possessing only slightly less egregious deformities, and so on—inverting and mirroring the social hierarchies of “normal” society. The last straw occurs when Boy escapes as a teenager, his eyes opened to the knowledge of his own monstrosity, of his perceived inferiority, and of the reality of pain and death. A slanted Eden, the Garden of Monsters, too, is destroyed by catastrophic knowledge. In Donoso’s twisted reenactment of the Fall, there is a yearning for lost wholeness, that recurring dream of the Western mind. That some final reconciliation might yet destroy the categories that demean and exclude humanity from itself remains both tantalizingly close and the punchline of an enormous cosmic joke. The novel’s contentions refuse to resolve; the monsters will have their revenge.

Donoso’s masterpiece is one of the great novels of retribution in world literature, a tale of little people pushed beyond the limit of endurance, a collection of losers achieving a terrible, pristine vengeance. The moral authority of the servant, the witch, the monster, and the mute precisely parallels the depth of their humiliation. Long submission has necessitated the stealthy accumulation of power and potency. Information, cunning, gossip, black magic, “their employers’ fingernails, snot, rags, vomit, and blood-stained sanitary napkins,” the whole of it achieves here the furious momentum of a downtrodden continent:

Keep in mind the power of miserable creatures, the hatred of witnesses, it may be buried under admiration and love but it’s there, don’t forget the envy of the insignificant and the ugly and the weak and the lowly, don’t forget the talismans they keep stored under their beds or in their mattresses, the vengeance of those who’ve expiated your guilt.

Neither the rich, nor the powerful, nor the noble, nor the pure can survive the novel’s terrible symmetries. Peta Ponce takes over the body of the present-day Inés and ends up in a psychiatric hospital; Jerónimo de Azcoitía is robbed of a son and a wife; Don Clemente, Jerónimo’s father, is manipulated by María Benítez, his cook, “who was frequently caricatured in an insolent political lampoon as the embodiment of the oligarchy, a lady using a huge spoon to stir a cauldron labeled with the country’s name”; and the old women inherit the Casa under the new legend of Blessed Inés and her holy child, putting an end to the profitable development of the land.

In these reversible tales of domination and submission, it is Humberto Peñaloza whose fate best exemplifies the dark brand of justice at the heart of the novel. Following a breakdown at La Rinconada while overseeing the estate’s population of monsters, Peñaloza is operated upon by the nefarious Dr. Azula, who harvests his organs and limbs along with his identity:

Azula cut out the eighty percent of me that included Humberto Peñaloza the writer, Humberto Peñaloza the great man’s secretary, the Humberto Peñaloza in cape and slouch hat who recites poems in bars, Humberto Peñaloza the son of the grade-school teacher who was the grandson of the engineer on a toy train that belched so much smoke that it’s impossible to see beyond him. Yes, Dr. Azula robbed me of that modest background, leaving me converted into this pitiful twenty percent.

His body parts are grafted onto Jerónimo de Azcoitía, so that he might yet produce a viable heir. But even in this shocking transgression, the former writer steals a kind of victory from the jaws of defeat: his penis having replaced Jerónimo’s impotent member, it is Humberto Peñaloza who now commands the Azcoitía bloodline. It is a revenge that costs him everything—organs, legs, voice, history—but a revenge nonetheless, the “privilege of misery,” as he has it.

This is how we discover the genesis of Mudito, the voiceless, disabled, scheming skulk confined to the Casa, a man formerly known as Humberto Peñaloza, now a floating, hyper-intelligent awareness trapped in the twisted body of the neo-imbunche. That folkloric creature encircles and binds the novel, a kind of ordering principle. As it is told in one of the Casa tales, the imbunche is a kidnapped child whose orifices are sewn shut by a coven of witches before its bones are broken and its head turned around so that it is forced to walk backwards. Many kinds of imbunches inhabit the novel, stacked one upon the other: the landowner’s daughter, cloistered in the Casa, deprived of magic and experience; Boy, trapped in his crumbling, synthetic utopia; the Casa itself, its windows boarded, its rooms walled off; and Mudito, the broken, vengeful writer. His final transformation—he assumes the role of Iris Mateluna’s divine infant, his chest and genitals shaved, his immobile body consigned to a throne—completes and perfects the myth. “I want to be an imbunche stuck into the sack of his own skin, stripped of the capacity to move and desire and hear and read and write, or remember,” Mudito says. It is Emperatriz, the dwarf administrator, who sees Mudito’s project for what it is: “It’s as if he’d lost himself forever in the labyrinth he invented as he went along.” The same might be said for José Donoso, whose miraculous novel is a sealed world from which, once encountered, one can never escape. ![]()

Dustin Illingworth is a writer based in Northern California. He has written for the New York Review of Books, the New York Times, and the New Yorker.