“I wonder if I haven’t simply explored and brought together in [this] text the twofold fascination I’ve always had with photography and the material traces of presence. A fascination, now more than ever, with time.”

—Annie Ernaux, The Use of Photography

I went to see Annie Ernaux at her home in Cergy at the end of April 2024. The travel time is just over an hour by RER suburban train (Réseau Express Régional) from where I live in Paris. Cergy-Pontoise is one of the “new towns” planned and created in the 1960s on the outskirts of Paris to relieve urban congestion. Ernaux has lived in Cergy since 1975, and most of her books have been written in her house there. The streets of the new town, the small businesses, the shopping center, and the public transport system, especially the RER, figure prominently in her books. This is especially the case with the “journaux extimes,” diaries of the outside world (Exteriors; Things Seen; Look at the Lights, My Love), as defined in opposition to the private, inward-turned “journal intime.” In the past decade, I have rarely traveled on the RER without bringing pages of translation to correct from Ernaux’s books. And in these pages, it sometimes happens that the narrator is herself traveling on the RER, observing, listening, and reading, though presumably not pages from a translation.

Annie Ernaux lives in a house built in the fifties on a great sweep of green, sloping land. On the side of the house in which her writing room is located, looking up, at the top of the hill and the road, there is a stand of fir trees. There are many different kinds of trees on the lot. I know this from the books but even more from my email correspondence with the author. There is a plum tree, a japonica, a magnolia, and when I visited at the end of April, the last of the lilac blossoms were scattering. During the pandemic, at the most restrictive period of lockdown, when I wrote to Ernaux with translation-related questions about Getting Lost, she very kindly sent me photos of whatever tree was blooming at the time. For May 1, it was an image of a branch of lily of the valley from her garden.

To return to our visit in April: we settled across from each other at the dining table in the double room whose French windows and a balcony look out on more leafy expanses, with a blue rim of hillside in the distance and a plunging view of the Oise Valley. We spoke for about two hours, in French. I came equipped with questions, soon abandoned, apart from a cheat sheet of notes and quotes. Our conversation took its own course, digressing and then backtracking in order to retrieve the dropped threads.

Annie Ernaux is a very engaging and vibrant conversationalist. She has a wonderful laugh. We started by discussing the books I’ve been translating, The Use of Photography (for release in fall 2024) as well as The Other Girl (2025). I was eager to inquire how these books came to be, for whenever I translate a book by Ernaux, I search for its roots in the oeuvre, the life, the project notebooks, and in the oeuvre again. We did move on to the subject, but talked of many other things too, such as Exteriors, the photo exhibition curated by Lou Stoppard and inspired by one of Ernaux’s journaux extimes, showing at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris. In the exhibition, excerpts from the book—originally Journal du dehors (1993), translated by Tanya Leslie (1996)—are displayed among the works of photographers, including Claude Dityvon, Daido Moriyama, Garry Winogrand, Dolorès Marat, Janine Niépce, and Ursula Schulz-Dornburg (to name only a few), from the MEP collection. (It is a wonderful exhibition, which I visited again after my afternoon in Cergy, this time with the catalogue in English that Ernaux gave me just as I was leaving.)

Photography is a fixture in the work of Ernaux, whose writing style has often been described as photographic, objective, neutral, even “flat” (her term, from A Man’s Place). Photos—in written form—are present in a number of Ernaux’s works, in which they play an essential role (“freeze frames on memories” is one way she describes them). Yet I don’t believe there is another work by Ernaux in which photography is so much the stuff of the book as it is in The Use of Photography. “It comes from a very specific project,” she said. “It came as a total surprise to me. I never thought I’d write it.”

Originally titled L’usage de la photo (Gallimard, 2005), the book was co-authored by Annie Ernaux and the photographer Marc Marie, who was her lover at the time. It evolved out of several months of photo taking by Ernaux and Marie over the year of 2003. For most of that time, Ernaux was undergoing treatments for breast cancer. Many of the photos they took are tableaux of clothing that have been shed and scattered before sex. Undertaken as a means of heading off loss and forgetting, the project would later include writing, on Ernaux’s suggestion. From among the forty-odd photos they had taken, together they chose fourteen to serve as their subjects.

Alison L. Strayer: In the beginning of The Use of Photography, you wrote a short chapter to introduce the project and how it evolved. I’ll start with an excerpt from the back cover text:

Often, from the start of our relationship, on getting up in the morning, I would gaze in fascination at the dinner table, from which the dishes had not been cleared, at the chairs out of place, our tangled clothes that had been thrown all over the floor the night before, while we were making love. It was a different landscape every time. . . . I wondered why the idea of taking photos of it did not occur to me before.

Annie Ernaux: Well, and then the idea did occur to me, not right away but quite soon. The Use of Photography developed from a very specific project, as did the other book you’re working on, The Other Girl. It emerged from a practice of photography. I checked in my diary—we started taking them in January or February 2003.

ALS: The meeting with Marc—“M.” in the book—was in January 2003.

AE: That’s right. We started taking photos very soon after, but in reality the writing project didn’t start until November 2003.

ALS: If you’ll forgive another quote, this one is from your journal of projects, published as l’Atelier noir. I looked up the year 2003, for which there are hardly any entries. On Saturday, July 12, you wrote:

Breast cancer, haven’t written anything since about the twentieth of January. I’m going to get back to it. This morning, wrote about “the year of cancer,” but that’s facile.

AE: I didn’t want to write about the year of cancer on its own. First of all, I didn’t know whether I was going to get better. There’s that, after all. It weighed on the writing. It is hard even now for me to imagine that just because the treatment stops and I’m told, “Well, there you go, done!” that right away I would feel saved.

It’s true that cancer is part of The Use of Photography and part of that whole year. I was supposed to be cured in July—in other words, the treatment stopped in July.

ALS: You wrote, “For months my body was a theater of violent operations.”

AE: When we started writing, our subject was the photos alone. But soon we realized we couldn’t do it without talking about cancer.

ALS: “The other scene,” which was absent from the photos.

AE: Yes, that’s right. Of course, that “other scene” had a great impact on the whole period. It gave it its intensity, I think. It was love against death. There’s no other way of saying it.

And it was certainly a book that shocked the journalists who wrote about it. For example, Josyane Savigneau from Le Monde, who always did very good articles about what I write, was very cold, really very distant with this text. In the Nouvel Observateur, it was also reviewed by a woman. Her approach was ironic. The title was “Ernaux se déshabille.”

ALS: “Ernaux takes her clothes off.”

AE: The review in Télérama I don’t recall now . . . Yes, it wasn’t pretty. I think you’d have to look hard to find a positive review. And there were two TV interviews. Their tone was “Well, we really don’t have anything special to say, but since we’re here . . .” and so on.

The word I’d use is “disapproval.” People disapproved. Of the photos, first of all. They’re unusual, they’re not what anyone expects. No nudity—you don’t see bodies, you see clothes. Things then weren’t the way they are now, with people taking photos everywhere with their phones. This was 2003. We were taking photos with a camera, an analogue camera that took very beautiful photos—it was Marc’s camera, not mine. I don’t know . . . They disapproved because it hadn’t been done before. Certainly not by a woman with breast cancer.

ALS: Did you have a sense that people considered it irreverent?

AE: Yes, well, when you have cancer, pleasure is not allowed. End of story. You do your chemo and you don’t bother other people with all that. The less they see you, the better it is for everyone. Because there’s that, too: people don’t talk. They don’t know how to be around someone who has cancer.

ALS: You wrote that you met with that reaction quite a lot.

AE: For them, you’re already dead. That’s how they see you. It’s as if you had something contagious. Or as if you were already on the outside, outside of life, and so on. That’s why I hid it as much as possible. Completely. Only my children knew. I told Marc because he’d made a date to see me, but I didn’t want him to . . . Well, it was a sort of a test of truth, you know, to say to him, “I’ve got cancer. Now what are you going to do?”

ALS: Early in the book, when you’re at the clinic—

AE: Not a clinic but the Institut Curie. Marc Marie was very present.

ALS: The relationship was already very close.

AE: It really started there. I had the operation quite soon after we met. And because—well, you know, it’s all in the text. It was a happy time.

ALS: It’s one of the parts that I like best. The snow, the rooftops, the quiet corridor sounds. Marc bringing you books.

AE: At the same time, it was against a backdrop of war, that of the United States against Iraq, in which the French weren’t taking part, but that didn’t stop people from coming out for huge demonstrations. When I was at the Institut Curie, there was one on the street just below. I could hear it all.

ALS: On the Boulevard Saint-Michel.

AE: Right, on the Boulevard Saint-Michel, all those young people marching. War was very present, people were waiting—we still didn’t know when the United States would descend on Iraq. It was all a huge lie that led to a pointless attack. In reality there was no reason for it. The war was looming until March. It was declared in March. And ended quite quickly because Iraq would be completely destroyed, Baghdad was destroyed.

After I came home, after the operation to remove my tumor (I didn’t know yet whether I would need more surgery), we started taking photos. We continued through October. Even up until Christmas, or New Year’s.

ALS: Yes, there’s a photo from Christmas morning.

AE: So it was right up until then. When the project was decided, we’d been taking photos for a while. By then it was November. The writing was something else entirely. It was my idea. I came up with the device, saying, well, this is what we’re going to do: together, we’ll choose fourteen photos—that was just a random number, there’s no particular meaning to fourteen—and then we’ll each write about the photos on our own. So we had the duplicates made, and so on.

ALS: So you didn’t show each other anything you wrote until the end?

AE: The texts were only put together just before I took it all to the publisher, in October 2004.

And I really don’t remember now how we thought about the photos, on their own, you know? Before the writing. I mean, I know that every time they came back from the developer, we looked at them with great, great . . . We found them very interesting. Quite weird too, some of them.

ALS: From the way that some of your writing about the photos is phrased (and I was very conscious of this, in translating), I almost felt as if the objects themselves, especially the scattered clothes, had decided where and how they were going to land. As if they’d done their own mises en scène.

AE: Yes, in a way they have a life of their own, in our stead. At the time, I received letters from readers who wrote, “Oh, I do the very same thing, I take pictures of what we eat in restaurants, the food on the table—”

ALS: The way we photograph so many things now with our phones.

AE: We photograph so many things with our phones now, yes. But with the photos Marc and I were taking, there really was an intention. For us, the scattered clothes were scenes, like paintings, still lifes, and they refer to the sexual scene. Because the scene of sex cannot be represented. X-rated films are something else, they have nothing to do with it. They say nothing about what beings are driven by, what’s inside them. Here, we have a form, that of the “other scene,” as people say in psychoanalysis, another scene.

ALS: Have you read the text by Virginia Woolf called “On Being Ill”?

AE: Maybe. I’m not sure.

ALS: It’s a great essay! At the beginning, in a very, very long sentence, she says something like “It’s surprising, given how common illness is, that it is not to be found among the great themes of literature.” She develops the idea that we have to find another way of evoking illness and other things that can’t be told in a head-on way. You can’t have a list of symptoms or descriptions of actions and gestures—something more oblique is needed.

AE: Yes. That’s it, yes.

ALS: The essay ends with an image of a velvet curtain that has been crushed together in one place where a woman has seized it in great suffering. She’s not there anymore, but the mark of her hand remains.

That’s what the photo is, here, in a sense. An imprint, a mark that resonates.

AE: Yes, it’s the trace that challenges, that makes us ask questions. And the trace, here, is a photographic print.

What can seem surprising is that for months we did these photos for no reason but to have them. And the photos could have served as the basis of an exhibition. You see? But it was another use that I thought of. I suggested it to Marc Marie one evening over dinner and that’s the form it took. We started writing right away, and we respected the rules. I was the one to draw up the rules.

ALS: We see a clear progression from the “hallway composition,” that first photo with the scattered clothes, through to the last one, which Marc says is “too beautiful.”

AE: With the dress that looks like a rock.

ALS: “The sand rose.”

AE: There is no feeling of flesh in that photo, there’s no body in it, none. It really struck me when I started to write about it, around Christmas 2003 or New Year’s Day, I can’t remember.

ALS: One feels it’s the end of something.

AE: Yes. I think throughout the book you feel the development of a relationship. Or rather the decline.

ALS: Is there a photo of Venice? I ask because that was another peaceful time for the lovers, similar to the days at the Institut Curie.

AE: We write about Venice, but there isn’t a photo.

ALS: I retain the “written photos” so much more than the prints in the book.

AE: The Venice text is where I talk about throwing my bra over the balustrade, isn’t it?

ALS: But it doesn’t really fall.

AE: It hovers.

ALS: It drifts over the garden of the cloister.

AE: San Giorgio. Yes.

ALS: And the elevator operator is a monk.

AE: I’ve been back to Venice since. We both went back. I don’t think the monk runs the elevator anymore.

ALS: He took people up to the bell tower and back while praying.

AE: Yes, yes! He sat on a little bench inside, reading psalms.

ALS: I was struck by how much travel you did. You went to Venice in what seems a very short time between appointments.

AE: Yes, the Venice trip was complicated from that point of view. Radiation therapy was every weekday. There was also a system of chemotherapy that I wore, a sort of flask hooked around my waist. The liquid came up through a catheter planted under my skin.

ALS: You describe it in detail. The pack at your waist with the bottle of chemicals, the harness system.

AE: Which I think was quite traumatic for people because it doesn’t exist anymore. They’ve made progress. They’re still making a lot of progress in oncology. They’re getting there. Well, the chemotherapy treatments aren’t as cumbersome.

I didn’t have more treatment after July because my cancer wasn’t, as they say, hormone-dependent. But it was a very high-grade cancer. The previous autumn I wasn’t sure at all whether I was going to live.

I can’t go back and read about it. You find out that you can die, just like that, from one day to the next! And you do find out like that, from one day to the next.

I had other reasons to feel dismayed—well, that’s an understatement. I had a cyst that—I know from my journal—was already there two years earlier, but when I told the gynecologist, he said it was nothing. Even in July 2002, three months before the diagnosis, when it was really showing up on my blood tests, I told him, you know, it hurts. The cyst was painful. He told me, cancer never hurts, which is the worst kind of stupidity.

ALS: That’s awful.

AE: Obviously I stopped seeing him after. It was a very hard time.

But perhaps what The Use of Photography shows very clearly is that in my relationship with Marc, and even through those photos and the writing, I found a way of living above life, in a sense.

ALS: Yes, I understand.

AE: And therefore above death. And I can’t be sure but sometimes I think that if I recovered, that is why. They say that the state of morale counts for a lot, and keeping my morale up meant ignoring the cancer and thinking about something else completely.

ALS: You were both very matter-of-fact about your cancer and carrying on regardless.

AE: Because when we met, we did not dramatize it at all.

ALS: Where did the book’s title come from?

AE: That was my choice, again. I don’t think it was a good title, I admit that. Because to begin with, what use can you make of photography? Well, I suppose you could say that this was one use. It’s a use and a practice of writing, a practice of life in the same way that writing is.

Did you know that the booksellers at first classified it as a technical book on photography?!

ALS: You write: “In the old missals there was a special prayer for asking what the proper use of illness was. As I think back now, it seems to me that I have made the best possible use of cancer.” And it was a good use of life, as you say elsewhere in the book.

AE: Yes, it was. In effect, it had to do with ignoring the illness in a certain way, even though I knew it was there. Just because I had cancer—breast cancer, moreover—didn’t mean that I had to refuse what was almost a miracle, of love. It was a miracle.

ALS: I’d like to talk about translating descriptions of photos, which were an important part of this book. And photography plays a big role in other books of yours too, such as The Years, or even A Girl’s Story, and certainly The Other Girl, too, which I’m now working on. I’m referring to the “written photos” as you call them—there are no photo reproductions in most of the books. I apply a lot of effort to translating these descriptions, and I tell myself each time that it shouldn’t be so complicated: it should be straightforward because they are so precise. There are shapes and angles, and you say where things are positioned in relation to each other (“perpendicular to,” etc.). The photos in your books are meticulously described.

AE: There’s nothing harder than describing things from reality. These aren’t made-up descriptions.

In The Use of Photography what was very, very difficult is that I was starting from an impression, not just what you see.

ALS: That’s a distinction that I’m not sure I grasp. Though I’m working on it!

I noticed—and it’s interesting to see—how you and Marc started each text from a different angle. I mean, you each chose a different starting point in the photo, or it chose you, and after that, too, the text developed quite differently. Though there were similarities.

AE: But it’s not the same thing at all with The Years. When I talk about a photo in The Years, I describe what she is thinking about, her memory, and how she sees the future, and how she feels in the present. But there’s none of that in The Use of Photography. What we had before us and had to describe were more like paintings. Really like paintings. To describe an inanimate object and to describe a living being are not at all the same thing. That’s precisely what we were up against. These photos are still lifes. It’s presence that we had to describe. ![]()

Alison L. Strayer is a Canadian writer and translator. She won the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation, and her work has been shortlisted for the Governor General’s Award for Literature and for Translation, the Grand Prix du livre de Montreal, the Prix littéraire France-Québec, and the Man Booker International Prize. She lives in Paris.

Annie Ernaux, the author of some twenty works of fiction and memoir, is considered by many to be France’s most important writer. In 2022, she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. She has also won the Prix Renaudot for A Man’s Place and the Marguerite Yourcenar Prize for her body of work. More recently she received the International Strega Prize, the Prix Formentor, the French-American Translation Prize, and the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation for The Years, which was also shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize. Her other works include Exteriors, A Girl’s Story, A Woman’s Story, The Possession, Simple Passion, Happening, I Remain in Darkness, Shame, A Frozen Woman, A Man’s Place, and The Young Man.

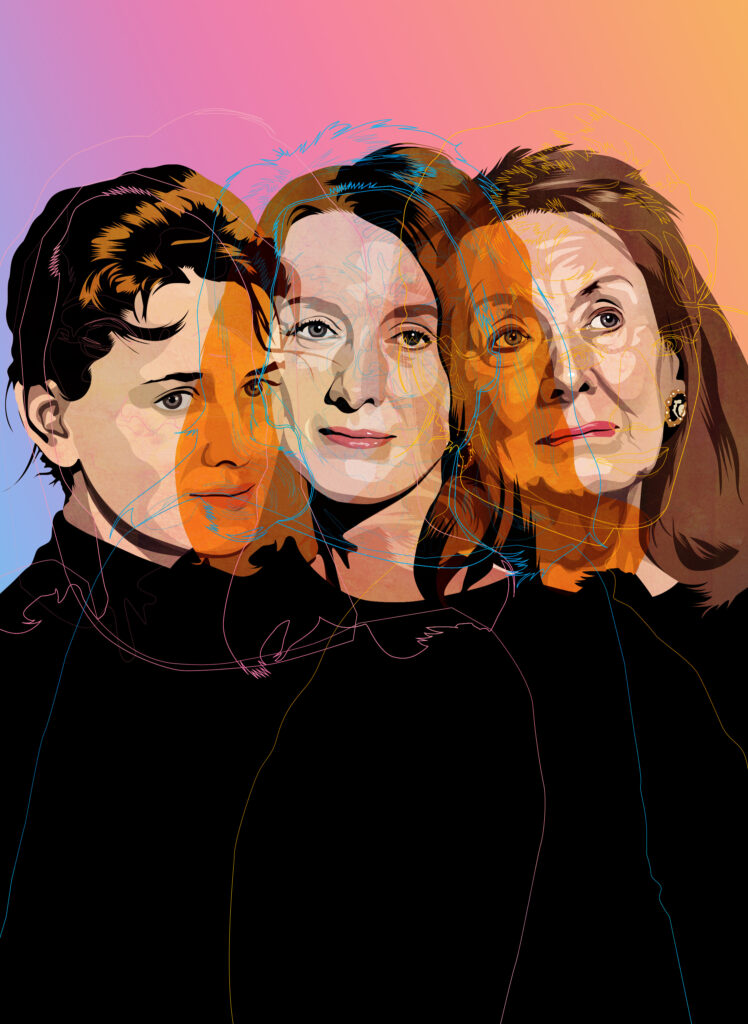

Illustration: Alvaro Tapia Hidalgo.