Like many Americans, I have a terrible job. Week in, week out, I work with some of the stinkiest, most ignorant people on the planet: teenagers. I am a high school teacher. Every day, I lace up my boots, hike several miles through the snow, and bounce into class with a smile to lead my young charges to a deeper understanding of our modern world. They are unimpressed.

A few weeks ago, I was sitting in a corner of the classroom, my head in my hands, as my partner teacher began talking about the Rolling Stones. She was introducing an assignment that would require our ninth-grade students to evaluate the career of the band in critical terms, and explaining that quoting Wikipedia would not be allowed.

I saw my chance and I stood up. Sites like Wikipedia and Britannica.com strive to be neutral, I explained, but when you want to understand prolific performers like the Rolling Stones or Taylor Swift, you need a guide—a gatekeeper—to sort out their best songs from their clinkers. “Professor Geppert and I are talking about the importance of critical analysis,” I said.

That’s when a girl in the back row raised her hand and asked, “Okay, but it’s important to have a neutral source, right?”

In a world such as this, it’s not easy being a Butthole Surfers fan. The layperson hears the band’s name, chuckles, and moves on. Of course, the Texas group has its advocates—after all, The Simpsons’ creator Matt Groening included a Buttholes joke in a key episode of that greatest of all American television comedies. But even diehard disciples tend to rave about the band’s bacchanalian live performances and underplay their discography. The critical assessment of the Butthole Surfers’ music has been begrudging: in 1989, when the band was at the height of its powers, I recall loitering in the offices of Spin magazine, trying to convince two very eminent record critics that this was a great band. They were unimpressed.

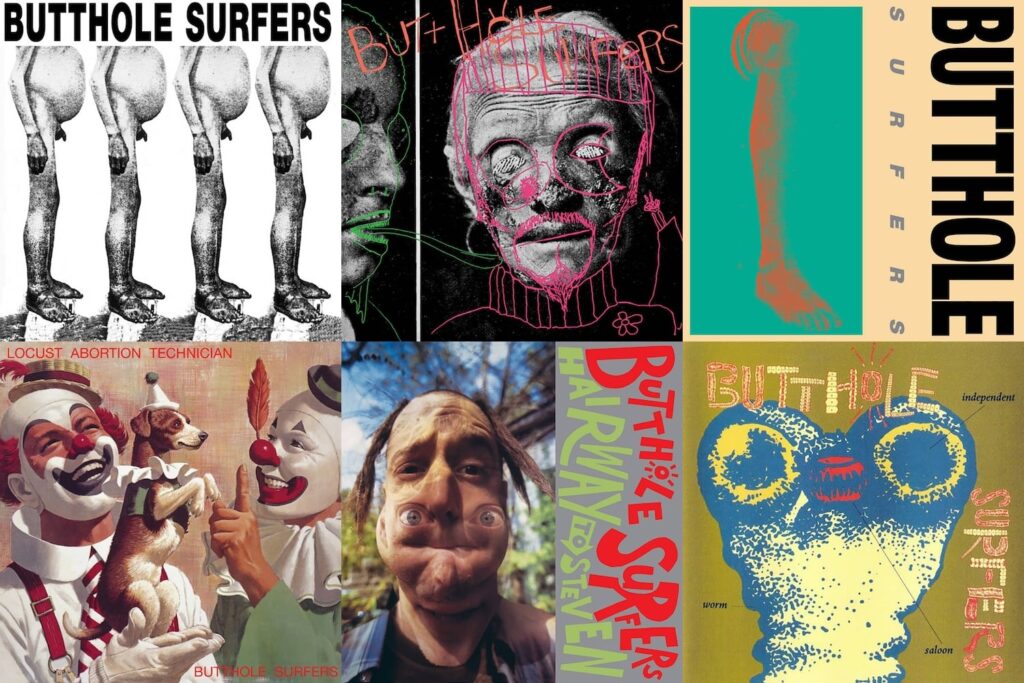

Against this backdrop, I offer you a principled and almost completely serious defense of the recorded works of the Butthole Surfers. For the uninitiated, the Butthole Surfers coagulated in San Antonio in 1981. The band—which has never officially disbanded—has been led by guitarist-singer Paul Leary and lead singer and multi-instrumentalist Gibby Haynes, and most famously accompanied by drummer Teresa Taylor (aka Teresa Nervosa, RIP), drummer Jeffrey “King” Coffey, and bassist JD Pinkus. They have released twelve albums and a handful of significant EPs: two of these I cannot listen to, one features a Top 40 hit, two are mid-period mistakes, four are excellent romper-stompers, and three are absolute classics of post-punk, post-whatever, independent, and utterly singular art rock. They are absurdist-savants, and would be seated at the same table as Captain Beefheart, Devo, and the Beastie Boys in a real Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, if we had one.

![]()

The Buttholes’ first record, officially untitled but sometimes referred to as Brown Reason to Live, was released in 1983 on Alternative Tentacles, a label founded by Jello Biafra, singer for the hardcore punk band the Dead Kennedys. That is the first of many layers of irony in the record—the in-jokes would be unbearable if they weren’t so funny and musically compelling. It begins with a squeal of feedback and the band’s most “hardcore” tune, “The Shah Sleeps in Lee Harvey’s Grave.” The song doesn’t have a chorus, but someone behind the amplifiers can be heard screaming, “No! No! No!” Full disclosure: at the time, Leary and Haynes were fed up, as were many Texas punks, with the strictures and regulations of US punk.

They follow this with “Hey,” probably the most perfect pop song the band would ever record. It’s almost winsome, and includes the rather too revealing lyric, “I’m not fit to fall in love.” It’s already clear that Leary is a virtuosic guitar player, although he prefers to play solos that sound like someone losing consciousness. The spooky “Something” is augmented by a majestic horn section, like a sort of oddball parade march. In effect, the band’s debut rejected punk-by-numbers and instead embraced a cobwebby attic full of all the other sounds punks could explore, if they dared.

Their next record, Psychic . . . Powerless . . . Another Man’s Sac, was their first full-length album and the first to feature the ritualistic double-drumming team of Taylor and Coffey. It was also their first record for Chicago-based Touch and Go Records, who would loyally support the band during this, their most golden period. “Cherub” is one “highlight” of Psychic . . . Powerless . . . and probably the first truly sinister moment in their oeuvre: it’s driven by a predatory bassline, whooshing electronics, and Haynes’s inscrutable invocations of an angel. As Leary has said of the album’s title, “Cherub” doesn’t make literal sense, but it sounds “kind of bad.”

More significantly, the Buttholes here begin to reveal a group persona that is demented, accomplished, and undeniably Texan. They drizzle their own theme song, “Butthole Surfer,” with a slightly Western melody. They pay tribute to an Austin punk legend (and major influence) in “Gary Floyd,” but turn the real-life singer for the Dicks into an amalgam of all the contradictions of Texan manhood, from heroism to vengeance, and top it all off with the kind of distorted blue guitar solo that animated tons of the psychedelic garage bands in Fort Worth and Austin in the 1960s, which was punk before punk. The biggest tell of the album is “Mexican Caravan,” which resembles a more melodic take on the avant noise that Sonic Youth was engineering at that very moment in New York City. Except that here, Haynes and Leary holler, “Take me, Mexican caravan / South of, south of the Rio Grande . . . Teach this white boy to be Mexican!” As someone who has eaten at Taco Cabana with the Butthole Surfers, I can certify that this was less cultural appropriation than an acute case of South Texas racial dysphoria.

![]()

The band’s next record, a four-song EP called Cream Corn from the Socket of Davis, really stood out from the army of R.E.M. clones who were starting to ring across the airwaves in 1985, at least on American college radio stations. The highlight of Cream Corn is “Moving to Florida,” a heavy swamp stomp that somehow reinvents Led Zeppelin for the 1980s, with Haynes ranting like a stand-up comedian at the edge of the fifth dimension. “I’m gonna build me the atomic bomb,” he gibbers. “I’m gonna hold time hostage down in Florida, child!”

By 1986, the band was touring the USA almost nonstop and living like animals in the back of a U-Haul trailer. But that’s not why Rembrandt Pussyhorse orbits away from punk rock so far that it’s unrecognizable as such. The backwards violins heard in “Creep in the Cellar” were discovered accidentally by the group when they reused an old reel of tape in the studio; the track could be mistaken for a home-recorded oddity from 1972. The band’s love for schlocky arena rock surfaces in their cover of the Guess Who’s “American Woman,” but it sounds more like a warped response to the arch, synthetic big beats of English new wave groups like Art of Noise or even Frankie Goes to Hollywood. They had foregone authenticity (the fatal flaw of many underground bands of the time) and were now locked in a passionate embrace of artificiality and the brightly colored garbage of American culture.

Other freethinkers around the USA were listening keenly. Bruce Pavitt, the man who would later launch Sub Pop Records and a band called Nirvana, reviewed Rembrandt Pussyhorse for Seattle alternative weekly The Rocket. “The coolest record ever made,” he wrote, before continuing, “This unbridled, surreal burst of imagination is enough to erase years of indoctrination by schools and television viewing. It’s finally OK to do whatever the fuck you want. We can only go up from here.”

In New York City, former Electra Records executive Terry Tolkin was confused when he heard the band. “I played their first EP, and I thought it was a compilation record by various artists,” Tolkin said. If he hadn’t become an ardent fan and co-conspirator with the Buttholes, he would have been even more disoriented by their next album, Locust Abortion Technician, which is often regarded as the group’s hallucinogenic masterpiece. It begins with a hilarious skit and a glue-sniffing reanimation of Black Sabbath, then things get strange. “Pittsburg to Lebanon” turns Texas blues inside out and adds spooky-ooky vocals. I would claim that the monolithic riffs and grunts of “The O-Men” is a nod to black metal, except that the genre did not yet exist. And “Graveyard” is simply a bad acid trip, a woozy, wobbly blast. Why take drugs when you can listen to the Butthole Surfers play the sound of them?

Yet this is exactly the mistake that casual listeners make—dismissing Buttholemusik as incoherent LSD jams is a bit like dismissing free jazz as random noise. The Locust track that vaporizes this argument is the unsubtly entitled “Kuntz,” a warped reprocessing of a Thai luk thung song. In 1987, in the middle of a Butthole Surfers record, “Kuntz” seemed like just another trippy interlude to some. I hear it as the secret of this album. At exactly the moment when American post-punk was diversifying and seeking out new inspiration like tendrils of ivy climbing a wall, the Buttholes were engaging with everything—and finding weirdness everywhere. They were stupendous listeners.

For me, it all comes to a head with 1988’s Hairway to Steven. The songs on this exquisitely strange and Day-Glo record don’t even have names, just scatological runes. The first track is malevolent and nightmarish from the jump. If a song can be understood as a narrative adventure, the narrator here is a cartoon monster, taunting the listener from atop a wall of screaming, scraping electric guitar. There are traces of sixties distortion and seventies prog rock as the number morphs into a psychedelic gale force, barely anchored to earth by two or ten incantatory floor toms. Alvin and the Chipmunks cackle and scream from a hellscape of sheering metal. It would be super creepy if it wasn’t so comic, but this is the crux of the group. Horror? Comedy? What’s the difference?

Hairway to Steven contains other songs, but honestly it all blurs together into one long, synapse-shredding trip. If Jordan Peele remade Walt Disney’s Fantasia, bled all the colors and figures of the original together, then tried to get every rock band ever to record the soundtrack but couldn’t, he might use Hairway to Steven instead. At the time Hairway was recorded, both David Lynch and David Cronenberg were exploring the dark side of the American dream. The Butthole Surfers belong in this company. Their music writhes below the worms and poisonous millipedes teeming beneath the stones under our everyday feet. It’s always there—insinuating something unspeakable, and making fart jokes.

![]()

But then the band stumbled. In the next five years, the Butthole Surfers changed labels twice, lost drummer Teresa Taylor, and released several inessential records. The Widowermaker EP and Piouhgd album aren’t bad, but they sound like rehashes. The latter includes a cover of Donovan’s “The Hurdy Gurdy Man,” which is sort of funny. As the Jackofficers (geddit?), Haynes and Pinkus recorded a technoid dance music record, Digital Dump, that was brave but lifeless.

Yet the world was changing under their feet. The art-metal band Jane’s Addiction started selling more records and playing arenas, and then Nirvana surprised everyone with a post-post-punk hit that was almost immediately branded “grunge.” Both groups were Butthole Surfers fans, and the Texas band’s fate took a bounce. Their first break seemed reasonable: Jane’s Addiction singer Perry Farrell asked the Buttholes to join his hotly anticipated festival tour, Lollapalooza. Their second break was unbelievable: in 1992, the Buttholes signed to the Capitol label, which had once been home to the Beatles and, even more importantly for Leary, Grand Funk Railroad.

John Paul Jones, bassist for Led Zeppelin, produced the Buttholes’ major-label debut, Independent Worm Saloon, and it’s a scorcher. The opener, “Who Was in My Room Last Night?,” is schizoid and metallic, but not heavy metal. Thick black hairs and melody sprout up out of nowhere. On both “Goofy’s Concern” and “Some Dispute over T-shirt Sales,” the band uses ever-escalating riffs and drag-strip time changes to fuse seventies hard rock with a post-punk slice and dice; their new mutation is muscular, but still pretty dang weird. The Chipmunks from Hairway to Steven have returned, but now they’re headbangers. Elsewhere, the group takes on British folk rock and even returns to its hobby of creating new genres with the acid bluegrass of “The Ballad of Naked Man.” It seemed like the first salvo of a gnarly new phase.

Instead, the next step was the last and most fantastic twist in the tale of the Butthole Surfers. The first sound we hear on Electriclarryland, the band’s second major-label record, is Haynes cackling and asking, “Alright, what are we doing here?” Good question. “Birds” isn’t terrible, but it sounds like an outtake from Independent Worm Saloon. The chorus of “Cough Syrup” is a Xerox of a Hairway track. Elsewhere, the Buttholes devolve into self-parody and hillbilly shtick, particularly with the crap country of “TV Star.” The band had spent years terrifying audiences and offending parents, but the most shocking thing about the single “Pepper” was that it was the first Butthole Surfers song that sounded like someone else. The second most shocking thing was that it became a Top 40 hit.

Against all odds, a band who had chosen the most hilariously uncommercial name ever became a mainstream success story. I believe that had something to do with their brilliant, compelling albums of the 1980s. At their pinnacle, the Butthole Surfers created a psychedelic howl that was entirely their own yet also plugged directly into an inheritance of Texas rock and blues that stretched back through ZZ Top and the Thirteenth Floor Elevators to Blind Lemon Jefferson. Their last records—including an almost unrecognizable thing called Weird Revolution—do not diminish their achievement.

In 2015, a journalist interviewed Gibby Haynes and suggested that the Butthole Surfers had sold out. The singer’s reaction was instructive: “Yeah, but who cares?”

Indeed. Long may they rave. ![]()

Pat Blashill was born and raised in Austin, Texas. He has written for Rolling Stone, Wired, GQ, and the Süddeutsche Zeitung of Munich, Germany. He is currently working on an oral history of Texas punk for publication by the University of Texas Press. He lives in Vienna, Austria, where he frequently tries to get his family to listen to the Butthole Surfers.