My mom’s boyfriend slithers up through the hole between the world downstairs and my bedroom in the attic. He’s grinning like he’s got a big, exciting secret. I can’t even begin to guess what it is and I don’t really care because I’m coming up on hour four of my first ever playthrough of Final Fantasy VII.

“I got something for you,” he says through a smug grin, like he’s thinking, I’m finally about to win you over. I figure it’s probably one of those Costco muffins he’s always eating—the chocolate chocolate chip kind that feels like you’re eating an entire cake condensed into the circumference of a muffin. What else could he even think he had to offer me? I’m thirteen or fourteen and he’s a contractor or a construction worker or something like that—I never really bothered with the details.

He hands me a brick. “I nabbed this today at work,” he says. “It’s a brick.”

“Yeah. A brick. I see that,” I say. In the background Cloud from Final Fantasy VII has his little block hands on his little polygon hips, waiting for my attention.

“It’s a brick from the greenhouse where Kurt Cobain shot himself. It might be worth something.”

I think about how greenhouses don’t have bricks.

“The house is going on the market and they’re doing some updates and when no one was looking I took the brick.”

I don’t know what to say, so I ask if there’s blood on it. I do not want there to be blood on it.

“I dunno,” he says. “Bricks are already kind of blood colored”—he says this like it’s some kind of trade secret—“but you love music, so I thought maybe you’d want it. To keep or sell.” It really seems like he wants me to make some money off this brick. Like he’s got a fantasy about us living large off this brick. He places it carefully next to the lone attic window and melts back down the ladder.

![]()

Monoculture is dead, I think? It’s sort of unclear, actually. When we speak about the current state of pop culture, it’s not uncommon to say that monoculture is dead. Usually, to back this up, someone will reference an antiquated event that they are absolutely sure could not happen today: All those people watching the Seinfeld finale in Times Square, the release of the first Star Wars movie transforming cinema, hundreds—thousands?—of teens screaming for NSYNC outside MTV’s all-glass Total Request Live studio at the end of the twentieth century . . . you get the idea. People got together in public to be really enthusiastic about something because it was, simply, how you tended to have shared experiences back then.

These moments exist in direct contrast to how we experience art now: we engage with it almost solely at our own convenience, usually while alone or by wearing headphones to make ourselves feel alone. When truly communal moments become infrequent, everything becomes more diffuse, made ephemeral by our human predilection for customization. If everything is easy to access and basically all of it is pretty good, it starts to feel like nothing—or almost nothing—can actually break through. This is not entirely true, especially when it comes to music. The democratization of recording equipment, the internet-abetted proliferation of hyper-geographic micro scenes . . . there’s never been a better time to make music where, when, and how you want to make it. There’s never been a worse time to be heard.

![]()

The kids on TV are crying because Kurt Cobain has killed himself. There’s a vigil at the Seattle Center near this domed fountain that shoots jets of water in every direction at once. It looks like a mad scientist’s thinning hair, sticking straight up and out like that. A few years after I see the vigil on TV, I am at the fountain. I watch a man climb to the top, slipping on the ceramic nubs he’s using for leverage. A jet of water launches him off just as he begins to hoist himself onto the very top; his body moves through the air in a long, slow arc before smacking against the pavement. I expect to see blood, but there is no blood, just a vibrating aura of pain and shock while we wait for the ambulance to come.

Right now, in the past, the kids are lighting candles and tossing flowers and crying. At day camp we try out adult sadness and tell the counselors that we are devastated about Kurt. My friend writes KURDT with the silent D on his jeans like people sometimes used to do. We don’t talk about how even a year ago we had no idea who he was, and often confused “Nirvana” with “Madonna.” We expect commiseration from these mature souls. Instead, one of them says, “Who cares. The Grateful Dead are better anyway.” A year later, Jerry Garcia is dead too.

![]()

“If a tree falls in the forest and nobody is around to hear it, does it make a sound?” is one of those infuriating thought experiments that, when you begin to really, truly think about it, yields only a vortex of logic problems and hypotheticals. It’s also a great way to describe the experience of listening to modern music. Only, it’s not that no one is listening, it’s that everyone is listening all the time, but no one is talking. So here’s my definitive answer: A tree falling in the forest does make a sound. Of course it makes a sound. But if no one is around to talk about it, how do we know it actually happened?

I admit that when you extend the thought experiment into the realm of music, this whole thing becomes an attractive overstatement. People are talking about all sorts of great music constantly, it’s just that we’ve reached such a high level of oversaturation without bifurcation—in other words, every song, every album, is presented as a lumpy mass of vibes that could theoretically soundtrack the life you may or may not be living—that it’s hard for conversation to rise above the noise, because there is so much noise. The question then becomes, “Is this a problem?” Maybe this decentralization is good, everyone is in their own corner talking about something different, ideas bubbling and humming just under the surface of mass popular culture.

Except mass popular culture—aka the top 1 percent of things the larger public cares about—is the stuff that ends up defining history. When we look at popular culture as a lens through which to understand a period of time, only a small fraction of art or artists get the opportunity to leave their mark. It’s a simplification of how it actually was. A shorthand. But it does become the understood narrative.

In the introduction to his book Major Labels: A History of Popular Music in Seven Genres, Kelefa Sanneh concisely tracks this divide: “Many people have a vague idea that in the old days, popular music was popular, and that somehow popular music got increasingly fragmented and obscure. We put on our headphones and escape from the world into our own curated soundtracks. But at the same time, many fans have kept faith with the idea that music brings people together, assembling audiences that cross boundaries. The truth, of course, is that both of these ideas are important and true. Popular songs or styles or performers can erase boundaries, but they can also erect new ones.”

This is all true. When pop music “succeeds,” it becomes something increasingly rare: a mass unifying cultural moment. The problem now is that the metric for success—for something to get the kind of traction that actually generates this sort of “where were you when . . .” experience—has gotten harder to hit. And the number of artists who can hit it—and then keep hitting it—is dwindling. Now, musical boundaries are not erected between genre purists opposed to each other. Instead, the wall is between the tiny fraction of the industry able to consistently hold people’s attention and literally everyone else.

![]()

First, we are all fascinated with chess. We are not even out of elementary school and the whole class is debating the merits of a knight vs. a rook. When the bell rings, we congregate in a room lit bright yellow. Mac LC II computers line the wall. On different days we are in there exploding drawings in Kid Pix or attempting to ford the river weighed down by too many supplies in Oregon Trail. But these afternoons it’s chess. All chess. We put on our headphones and take tapes out of our backpacks. Everyone is listening to Nirvana’s Nevermind, like we’d all just exited a meeting where they gave us copies and told us why it was important. We retreat into our fantasy worlds, each hearing something different in the same set of notes.

![]()

The first time I meet Lil B, he is not yet the architect of the term “based.” He has not yet released approximately 4536395290 songs. He has not yet written a book or played a show at NYU that saw a young, pre-fame Timothée Chalamet get on stage and bow down to his cult of greatness. Instead, he is part of a Bay Area rap group called the Pack, who are coasting off their megahit “Vans,” which features the lyric “Got my Vans on but they look like sneakers.” It’s a catchy phrase, but sort of mind-boggling in the same way “If a tree falls in the forest . . .” is. Aren’t Vans already sneakers? Is it worth mentioning that Vans look like sneakers if we already know they are sneakers? Does the Pack think that Vans are not sneakers? If so, what are Vans?

The Pack have come to New York to play a show in a small bar. There’s no stage. All the members are underage and they’re moving with a tentative nervousness, like they’re not supposed to be there. My roommate gets kicked out of the bar for dancing on a couch. It’s impossible to imagine that in a couple years, Lil B will be known for making, basically, outsider ambient rap music. Dropping stream-of-consciousness meditations on life and healing, engaging in a kind of inspiring artistic naivete that would be cutesy and annoying if it didn’t feel so necessary.

When Lil B achieves this, it is hard to figure out how to engage with it. He releases music so aggressively for no money at all. He’s cut himself free from the commerce part of making art, but lost none of the intention. In fact, he’s gained some. The problem—as the problem always ends up being—is in the way we remember and archive. Much of Lil B’s music is unavailable on streaming services like Spotify and Apple Music, which therefore means it no longer exists. If old MP3s are sitting on a dusty external hard drive in a drawer, do they still count? If evidence of Lil B’s influence over the term “based” has disappeared down to page sixty-five million of a Google search, did it ever happen? How do we tell the story of the years we lived when the evidence is so hard to hold on to?

Even indelible memories disappear eventually.

![]()

The rapper Lazer Dim 700 is from Cordele, Georgia. He sounds nothing like Lil B, but he could not be doing what he is doing without the existence of Lil B, whether he knows it or not. Lil B cracked something open the same way that Daniel Johnston cracked something open the same way that Bikini Kill and My Bloody Valentine and Animal Collective and Beat Happening and Velvet Underground and Timbaland and Missy Elliott cracked something open. They all reminded us about other pathways to creation within the realm of the recognizable.

Lazer Dim 700 releases a lot of music. Most of it sounds unmixed, his vocals gnawing through blown-out microphones. His music videos usually feature him alone in a house or an Airbnb, or somewhere else nondescript and lonely. He raps like he is trying to outrun every beat. On “Tony Dim” he’s rapping over what sounds like a malfunctioning Transformer, like we’re hearing every machine ever made die at once. It’s an acquired taste. As of this writing, it has two million views. Listening to him is exciting because you can hear all the rules fall away. It feels like a more accurate depiction of America in 2024—unsettled, nervous, confident, and lonely—than all of the big pop music that will retroactively go on to define what it means to live right now.

![]()

2023: When Taylor Swift plays in Seattle, so many people are moving in unison that they collectively cause a 2.3 magnitude earthquake.

1993: Kurt Cobain and the rest of Nirvana are taping their MTV Unplugged performance, half a year before Cobain kills himself. They end the set with a cover of Lead Belly’s “Where Did You Sleep Last Night.” There’s a part, just before Kurt lets out a bloodcurdling moan of devastation, where he breathes in and his eyes open wide, radiating pure pain. It’s so brief that you might miss it if you blink at the wrong time.

2001: The underground rapper Sage Francis is performing his song “Makeshift Patriot,” which is touching and a little ham-fisted and about the heartbreaking sadness of jingoism in the immediate aftermath of 9/11. While he’s rapping it, some guys behind me lock arms and start rapping—not along with Sage Francis, just to the same beat. They’re inspired by what he has to say but can’t wait to start saying what they want to say. All I can hear are voices drowned out by other voices.

2024: The outsider artist named Jandek performs in a cave. He acts like it’s no big deal that he is in the cave. He stands up there in his hat, rail thin, the cave lit by a couple of living room lights, like the cave is his regular home. He mutters, intones, almost chants. The cave feels like a structural embodiment of Jandek himself—at once ageless and ancient, unnerving in the wrong light, always there. I watch it and try to imagine explaining it to someone else. Maybe I’d say something about the acoustics and environment of a cave, or I’d talk about how, by making people come to some cave to hear his music, he’s taking the concept of outsider art as far as it can go, creating a blurry outline of a recognizable form in a space that is only in the vaguest sense a “space.” Maybe I’d say nothing at all.

![]()

Is there a difference between the experience of being around so many people that your collective movement causes an actual seismic effect and sitting quietly in a dim cave, watching a man coax lost spirits from an unsettled environment?

Is there a difference between hearing an underground rapper proselytize on a small stage in front of dedicated fans and Kurt Cobain feeling alone up there on that MTV stage, grappling with demons, his performance broadcast to millions of people?

Is all of this just an expression of art made in the margins, finding its way to people through a process that is equal parts label maneuvering, randomness, and cult of personality mysticism?

Is one thing more valid than the other?

![]()

“I had this weird upbringing of, like, thinking that I was the blood of the person who killed Jesus.” The musician and artist Ryan LoPilato tells me this over the phone. It’s the first time we’ve ever spoken, but I’ve followed his music career closely for nearly fifteen years. We’re talking about how he started making the music he now makes under a variety of aliases, including Haunted Houses, Credit Electric, and, most recently, LoPi. When LoPilato was a kid in Oakland, New Jersey, his grandfather told him he was a descendant of Pontius Pilate, the prefect who ordered Jesus to be crucified. LoPilato’s response to the claim was not to authenticate its veracity—how could he possibly do that? Instead, he dove deep into research of other religions and philosophies and started reading Nietzsche in an attempt to wrap his head around the weirdness he felt, even if he could never be sure that what his grandfather claimed was true. It’s an interesting story. Imagine being a lonely teenager and being told something like that. Your place in the world would be impossible to fathom. So much of our teenage years involves being told we have plenty of potential, while being treated like we have none at all.

Except even if his grandfather had never dropped that bomb, LoPilato probably would have been doing this kind of soul-searching anyway. He was a probing teenager, desperate to understand why he felt different and slightly out of sync with the rest of the world.

Suburban teenage alienation is at this point not novel. If you live in the suburbs, it’s practically a rite of passage. It’s what you do with it that ends up mattering. Maybe you scratch and crawl your way toward some semblance of productivity, and hopefully you put something out into the world that resonates—even if it’s with just a couple people. For LoPilato, his output—his artistic reason for being—took the form of the project called Haunted Houses, which cloaks doubt and dread under layers of warped guitar, drums stumbling just behind in a quixotic attempt to catch up to everything else that is happening. It’s an existential crisis put to tape, and it feels true because it’s not for anyone except LoPilato.

His tools were a cheap microphone, a starter guitar, and the weight of suburban ennui. When LoPilato started obsessively writing and recording songs, they sounded like what would happen if you took a speaker playing a Modest Mouse song and dropped a ton of gravel on top. Just enough so that the outline of the song was apparent, but all other elements took on a tactile feeling of dirt and sweat and frustration with unrealized dreams. “I didn’t like anything at the time,” LoPilato says. “I was in a dark place. I was finishing high school and I wanted to go to art school, but I didn’t get in, so I just kept doing what I was doing. I ended up [with my sound] through a limitation of not knowing how to perform like other people and being frustrated with that.”

And LoPilato’s music is a singular thing. Rooted in the immediacy of lo-fi, he makes music that sounds like a direct interpretation of what is in his head, played and put to tape before he can even second-guess it, his songs crumbling apart as he’s playing them. It feels like a descendant of American pain, the worn-out tragedy of the blues, updated for the twenty-first century. It’s music that has always existed, even when it sounded different.

Sometimes concise and piercing lyrics emerge from the murk—“I stand in line by myself” on “Yon Chills Hard,” or “I drank to forget frustrating truths or to celebrate eternal youth” on “A Crow Named September”—but it’s the murk itself, our frustration with not quite being able to understand his intention while still viscerally relating to it, that makes LoPilato’s songwriting so compelling. Across multiple albums, EPs, and loose tracks, LoPilato plumbs the depths of emotional dissonance—the loneliness of looking at your life and the world you inhabit and realizing that you see things in a way that other people do not. “I felt like there was something wrong with me, but everyone around me was telling me that everything was great and fine all the time,” he says.

The way he tells it, LoPilato was never looking for an audience. He was going to make the music he was making whether or not anyone bothered to listen, it just happened to be convenient that he could quickly upload songs to Myspace, at the time a burgeoning community for independent musicians. If that hadn’t existed? “I don’t know . . .” he says. “Maybe I would have turned to busking.”

The thing about Haunted Houses, the reason I’m writing about LoPilato’s music in this piece, is that he never really did break through, at least not in a way that turned him into a household name. His earliest releases were scattered across a couple small record labels, usually ones that specialized in cassettes. When I wanted to feel like my heart was rinsed clean of everything but the most white-hot emotion, or when I wanted to go scorched earth on my own sense of self, I put Haunted Houses on loud in my headphones and succumbed to the music in a way that felt so damaging that it looped right back around to cleansing.

I remember sitting on a bench on the end of a dock in the middle of the night on Fire Island, a tiny swath of land not far from New York City that has built into its history the increasingly terrifying prospect of getting washed away entirely by an unfortunately large wave or hurricane. Just being there provokes a sort of internal dissonance—it’s idyllic and feels like a lost way of living, but everyone there knows that it’ll all be gone one day, maybe even one day soon. Still, they keep building new structures, making plans for the next summer, smiling in the face of potential doom.

I was sitting there—stoned out of my gourd, staring at the distant twinkling lights across the bay, the low hum of a nearby water taxi droning just within earshot—listening to “Evil Practice in Ritual,” from the Haunted Houses cassette Make Believe You’re Dead, and I know this because the memory, though mundane, is imprinted on my brain over a decade later. I sat there, wallowing in self-pity, trying to figure out why life was the way it was—not for any specific reason, just for the general pain and frustration of knowing that there will always be more pain and frustration—and LoPilato’s voice emerged from a swamp of tangled guitars that were blown out way into the red, the drums barely holding the whole thing together. He was clearly singing words, but I could not, and still cannot, understand them. My heart lilted in time with his voice, I felt something primal. It offered no optimism, just a grim understanding that pain was the way the world moved, and that even though that was never going to change, that pain was what made it all worthwhile. It’s melancholic but often beautiful in its submission to despair. You know the feeling of reading a Cormac McCarthy run-on sentence that moves from violent terror to sheer beauty and back again, and how those sentences that become whole paragraphs feel like they’re communicating an essential truth about the emotional and physical violence of America? Listening to Haunted Houses is like that: it’s music not just for the lost and lonely, but for the lost and lonely who view those emotions less as a temporary state and more as an incurable symptom of being alive. And who, despite that realization, still find plenty of reasons to go on living.

![]()

For a few months, I am obsessed with a video titled “Lil Yachty with the HARDEST walk out EVER.” It’s thirty-one seconds long. In it, he’s about to perform his song “Coffin” at Lyrical Lemonade Summer Smash 2021. The camera tracks him as he walks from side stage onto one of those long T-shaped platforms that juts out into the sea of people in the audience. It makes him look like he’s walking the plank. Yachty is focused, and then his body slackens and he sort of shuffle-skips his way out there without a care in the world, presumably in time with the beat, which you can barely hear because the crowd noise is so deafening. Then, there’s a beat drop, the speakers blow out, the crowd jumps in unison, and the screen goes to black. The moment and the anticipation of the moment are the exact same thing. The power is not in what we see or hear, but in what we know is coming.

I was not alone in my obsession with this video. There are multiple uploads across multiple social networks with plays in the millions. It has been memed on the internet and memed in real life, too: The swagless rapper Ian performed on the same stage, doing the same sort of moves as an homage to Yachty. It looked the same, but did not feel special at all. Most recently, I saw, for some reason, a version where an AI Joe Biden—who inexplicably looked sort of like Mike Pence—was in the place of Ian who was in the place of Yachty, doing the same moves. An echo of an echo.

![]()

In the times of the old internet, but not the old, old internet, I used to watch this video of two teenagers lip-syncing to Korn’s “All in the Family” on YouTube. It’s a terrible song from Korn’s extremely popular album Follow the Leader that happens to feature Limp Bizkit’s Fred Durst on the cusp of superstardom. It is a facsimile of a battle rap, with Durst and Korn frontman Jonathan Davis trading limp, homophobic insults at each other for, like, five solid minutes. There’s no enthusiasm in it. No good jokes. Just directionless anger and an attempt to shock in a way that will resonate if you were of the right age at the height of early South Park mania and had some latent understanding of what shocking through edgy—“edgy”—gross-out jokes could mean; how they could seem dangerous or cool. How they could make alienation a badge of honor.

The video with the two teenagers has 2.3 million views. Comments are disabled. The reason for that, from the uploader himself, is: “I’m tired of idiots with no lives acting tough on the internet.” There is no better illustration of teenage boredom in the twilight of the twentieth century than this video. The Fred Durst clone’s baggy cargo pants fraying against sweltering parking-lot blacktop, the cutoff JNCOs on the Jonathan Davis imitator, the tone of the whole thing that says, “This is just us joking around, unless you think it’s cool or impressive, in which case this is us being serious”—this video is a depiction of complete apathy. It’s hypnotic. Without purpose, it’s all just landscape. Ambient noise that you recognize as shocking, but that doesn’t actually shock. It’s the late ’90s in a nutshell.

But it’s also showing something else: two kids in the middle of nowhere finding hope in a song made by artists who self-identify as outsiders—two kids who, for a few minutes, embodied who they hoped they’d become, then put it on the internet because they felt it so strongly that they couldn’t imagine other people wouldn’t feel it too.

Do you know what you are seeing?

Can you know what it is?

A tiny, inconsequential moment embedded deep, left to quietly fester. You are witnessing in this small moment the dissolution of the last pillar left holding up a teenage sense of self-worth, quietly eroded through a million small thwacks over the course of a short life.

What is the story we are trying to tell when we think about American music against the backdrop of an internet-aided transmogrification of popular culture? What happens when a pop song stops feeling special because it’s so big that it no longer feels like yours?

Kurt Cobain famously hated “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” Nirvana’s biggest hit, because it became so popular that it ended up misrepresenting what the band was all about. It started to attract fans who saw something in the song that Cobain did not. When it crossed over, it became a signifier for not just the year it was released, but a whole genre of music and the subculture behind it. It was no longer his. It was theirs. Now, it’s for all of us. It sounds good, still. It’s full of visceral anger, alienation, generational frustration about the failures of the institutions around us, still. But it feels like an echo of itself. A historical document of a moment, rather than a rush of emotion prompted by a moment. We’ll remember it forever, but maybe if it had slipped through the cracks a bit . . . maybe then it would hold some of that special magic that could make it feel like ours.

When we try to tell the story of our lives in the ephemeral years, where the concrete markers of culture—physical media, accurate data, context in general—have largely fallen away in favor of a morass of misinformation and a constant state of rewriting, what we’re really trying to do is hold on to a world we recognize, to not submit to the mass culture retcon that turns misunderstanding into general truth. We do this by holding tight to the personal moments we can’t or won’t share with the rest of the world.

![]()

Here is what I know about the fate of the Cobain suicide brick: My mom and the guy split up. She moved out. Packed up my PlayStation, my TOOL poster, and the futon I was using for a bed. A couple years after that, he smoked too much crack in the basement of his house and died alone. Someone probably threw the brick out when they were cleaning out his stuff to put the house on the market. Maybe it was already gone, or maybe it got thrown into the mix with other construction materials, and now a Kurt Cobain suicide brick is part of some Seattle chimney somewhere. Without context, a brick is just a brick. It’s a tool, not a talisman. If we’re being generous though, if we’re trying to hold on to some sense of concrete cultural history even as it all slips through our fingers . . . maybe then, a brick can be a bit more. It can be a vessel that holds stories that tell us who we are. ![]()

Sam Hockley-Smith is a writer, editor, and radio host based in Los Angeles. His work has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, the FADER, Pitchfork, NPR, SSENSE, Bandcamp, Vulture, and more. His radio show, New Environments, airs monthly on Dublab. He spends his spare time reading.

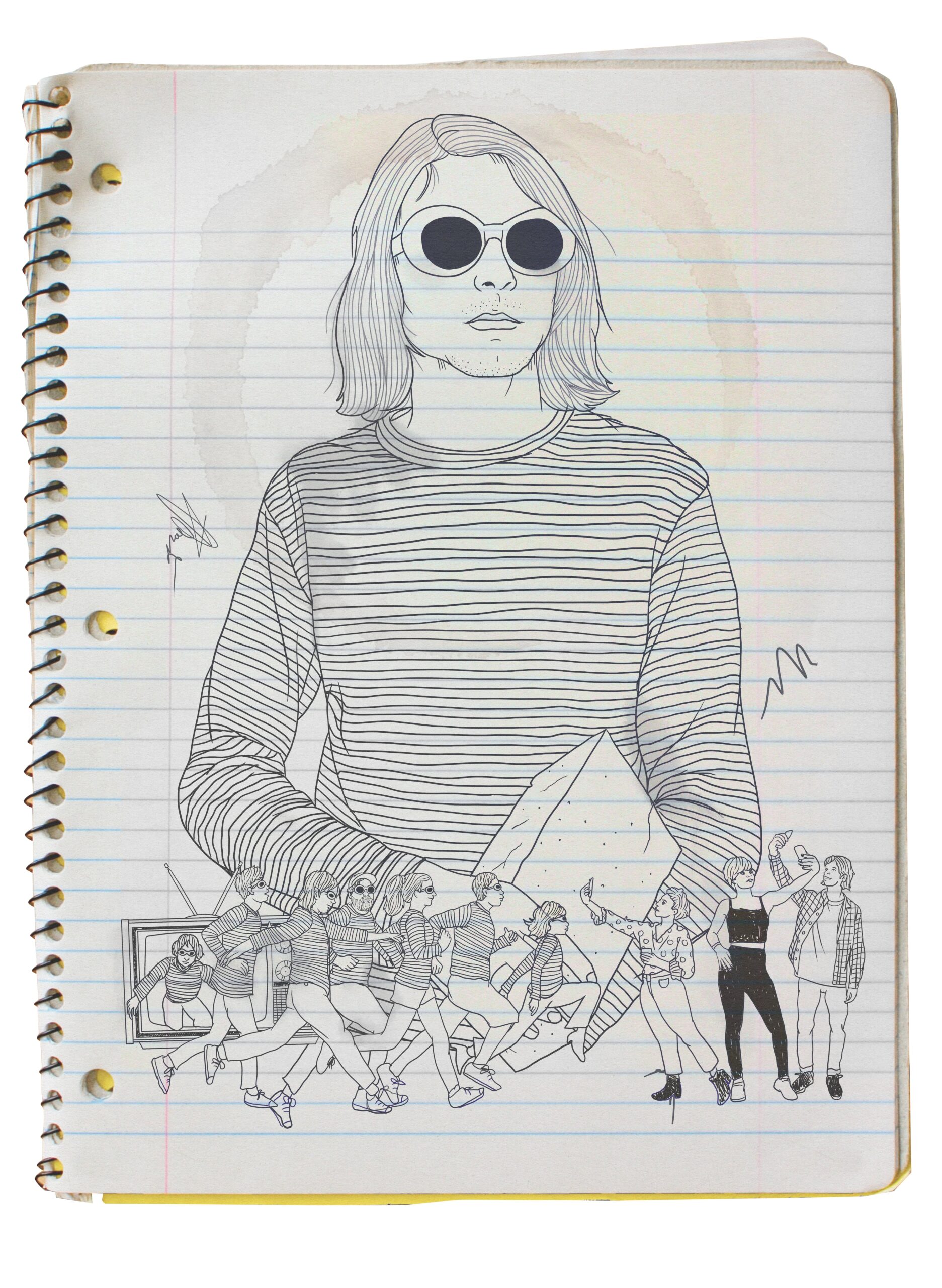

Illustration: Jess Rotter.