I first met Bun B on December 3, 2019, at White Oak Music Hall in Houston. We were both attending Red Bull Presents: Thee Outlaw, a branded concert for Megan Thee Stallion. Back then, Megan Thee Stallion was but a young Black girl from Texas aspiring to worldwide success. And Bun B was there as an elder, one who had spent years defending and protecting Houston’s claim to a hip-hop dynasty. I served in the role of archivist disguised as journalist, curious to see who had taken up Houston and the greater South’s claim to the throne of hip-hop. All three of us were admirers of the craft, and anxious about the possibility of a Houston rapper taking hip-hop’s reign with her hoards of hotties. All of us were bound by something UGK and so many other rappers from the Third Coast had laid down for us.

The South, Texas, and hip-hop overall owe Bun B a great debt. Alongside his partner Pimp C (Chad Butler), he formed the legendary hip-hop group from Port Arthur, Texas. Without the storytelling prowess of Bun B and Pimp C, the genre would not be the juggernaut it is today. Hip-hop has a direct through line to the oral tradition of African diaspora, and for this reason it stands out among other genres in pop music. Southern hip-hop in particular, which incorporates elements of gospel and blues, draws upon the deep lineage of African Americans using music as a way to preserve their heritage. When Megan Thee Stallion calls herself Tina Snow, an alter ego inspired by Tony Snow, Pimp C’s alter ego, in her discography, it’s more than a simple shout-out—it shows a deep reverence for the Southern rappers who came before her, for a tradition that still influences hip-hop today.

Bun B has witnessed the birth and evolution of hip-hop. (In fact, they share the same birth year: 1973.) At the age of fifty-one, he is also an author, an entrepreneur, a father, a grandfather, and a university lecturer. I had the opportunity to talk with him about the legacy of UGK, the history of hip-hop, and his later-in-life mission to pay it forward.

Taylor Crumpton: Let’s go back in time to when you were young. Tell me about the beginning of your career. Did you ever think that when you first started rapping, that you would have this legacy—musical children and grandchildren—who reference and revere you?

Bun B: When I found hip-hop, I was immediately a fan. I’ve always been a collector of music. Back then I was trying to find as much of it as possible because hip-hop wasn’t easily accessible in the earliest days. Every record store didn’t stock it. It wasn’t until certain people I knew started working at certain places [that I could find it].

Then, as the culture started to grow and expand into other regions outside New York, the stores started stocking more and more hip-hop, and people started to adopt different aspects of the culture. Some people became DJs, some became breakdancers, some became graffiti artists. And some people became rappers. In my city, Port Arthur, there was a group of people starting to create and record hip-hop music. Pimp C was one of them. He was already a practitioner when I decided that I might want to give it a try because I was good friends with a guy who was rapping and I was like, “He doesn’t even listen to as much rap music as I listen to. If he thinks he can rap, then I can rap.” I wrote a rhyme and it was terrible. But I wanted to be good. That was the fire that lit under me at the time.

But I couldn’t have imagined a life in hip-hop. At eighteen, nineteen years old, growing up where I grew up in the world that I was living in at the time, I couldn’t even imagine being fifty years old. I’ve been blessed with a slow but steady ascension in my career. I’ve been able to contribute to the culture in many different ways. My work is not always music based; I do a lot more speaking engagements now. This year, I’ve probably done as many speaking engagements as I’ve done concert performances. And of course I’m in the food industry [as cofounder of Trill Burgers in Houston].

Being open to change; being aware of a need to transition into other things—you end up exceeding expectations. Not only that other people had for me, but some that I didn’t even realize I had had for myself. I’m knocking down walls that I never even knew were standing in front of me thirty years ago. It’s amazing to me to be in the position that I’m currently in.

TC: One of my favorite things you’ve ever done. I’m so jealous I wasn’t in college at the time, when you were a lecturer at Rice in your hip-hop and religion course. For myself, who was raised in the church in Texas, I’ve always found Southern hip-hop to have a spiritual element, a gospel element, a Baptist element. I love that you’ve been able to bring hip-hop to all your endeavors—Trill Burgers, speaking engagements, being in the academy—and breathe life into them. It’s representative of what hip-hop can do and can become over time.

BB: Having the opportunity to use something that benefited my personal growth tremendously, and being able to apply that in a space to educate young people, is something special. If you look now, there are so many different spaces where hip-hop culture has been brought onto campuses and into classrooms to better meet kids where they are. It’s not about dumbing yourself down to reach children. We’re not trying to be hip or cool; we just want to let students know that we understand and have a frame of reference for the world that they’re living in nowadays. There’s always going to be comparable things that exist in childhood, like falling in love, social awkwardness. That type of stuff happens across the board, no matter which generation you’re from.

I currently work with a program called Reading with a Rapper. We’re going into classrooms and using hip-hop as a way to teach English. We show kids that when you listen and rap along to these songs, you’re not just singing. Alliteration, rhymes, similes—all of these different aspects of language are happening in these records. Metro Boomin is saying the same thing as Shakespeare and Dickinson. It’s about expression and exploration of the English language to communicate deeper with people.

And the kids take to it. By looking at some of the lyrics to the songs—not just songs from my generation, but some of their favorite songs—we can break things down and show them, “Hey, when this guy is talking about getting money, this is what he’s alluding to.” The teacher is taking them into consideration when putting together the lesson plan and as a result, they’re a lot more receptive. I’m so proud of being able to reach the minds of students.

TC: This is beautiful. Speaking of Pimp C, I was privileged to meet his wife [Chinara Butler] at Red Bull Presents: Thee Outlaw. It was so great to hear of her love for Megan. And on Megan’s recent album, she gave Megan one of Pimp C’s verses. I would love to hear about the process of you and Pimp being on “Paper Together,” because it’s also Megan’s way of informing her fans—who are younger, multiracial, and who span across the globe—about UGK, Pimp C, and the rap tradition coming out of Houston.

BB: People ask for stuff all the time. I don’t own anything lyrically or production-wise of Pimp C’s. The first thing that has to be addressed is through the estate. Just to make sure that everything legal is exactly where it needs to be, everyone gets exactly what they’re supposed to have due to them contractually. When the estate decides to hand something over, it’s got to be to the right person. It’s not necessarily about who wants to pay the most. It’s about who represents what it is that Chad gave his all for. It keeps his name and spirit alive, his energy alive. Then it gets to me and I’m pretty much all in. I couldn’t think of a better current artist to share a UGK record with than Megan Thee Stallion—she’s Tina Snow.

“Paper Together” was originally recorded as a reference track. The original version of it was more experimental. The original sample from the song was very different, and not the kind of music that rap was being performed to—it was a soul record, an R&B record. It had a groove to it, but not the typical groove and feel of hip-hop. That record evolved from the original version to another version and ended up in the archives. From my best estimate, the rhymes you hear are from when Pimp C and I were eighteen years old at the youngest, twenty-one years at the oldest. Those vocals were not re-recorded. It just shows how music can be appreciated across time. I think we did a good job with that on “Paper Together.” Because quite frankly, you can’t tell if that’s from the Dirty Money era, from the Underground Kingz era. You can’t really tell what era it’s from, but it’s distinctly UGK.

We always consciously tried not to time-stamp our music. When I say time-stamp—we were very careful not to have too many songs with the year in it. If you talk about cars, talk about models that are consistent in the brand, like the Mercedes 600. You know there’ll be a Benz every year. That line of thinking but also rapping about general things like love, hate, having money, not having money, feeling empowered, feeling small, being seen, being heard, being invisible—these are all human conditions that have existed for centuries.

But some people don’t understand the nuance. So there needs to be some clarity. That’s what Pimp C did best, more than anything else. If Pimp C wanted to get outlandish with the storytelling, there had to be clarity about what the overall message was because some people wouldn’t get it. You can hear it in “Pocket Full of Stones.” It’s a tale about being stuck in a cycle. If you sell drugs, you go to jail, then you come back out, you’re probably going to go right back to selling drugs, you’re probably going to go right back to jail, and now you’re caught in the cycle of it. At some point, you have to be clear about these things, especially in entertainment.

Kool Moe Dee had an album with a report card on the back—all the things that he was good at in terms of writing rhymes. One of them was sticking to themes. That really stood out to me. I’ve heard the Beastie Boys talk about the same thing: the ideas, the qualities that a songwriter in hip-hop should take into consideration when you write a rhyme. The topics of UGK songs may have seemed frivolous or outlandish, but there was deep thought that went into what we were saying.

TC: I was joking with one of my friends, Kathy Iandoli, author of God Save the Queens, that this year feels like the 1995 Source Awards. A lot of rappers are going back to a regional style. They’re wanting to represent where they’re from because, for a long time, everybody in hip-hop sounded like they were from the same place. I’m curious to hear your perspective. As someone who has witnessed the rise and ascension, how are you feeling about Texas hip-hop?

BB: I’ll be very honest: The South won, in terms of regional dominance in hip-hop. It’s very hard to argue [against]. It’s a numbers thing. You gotta go up against Texas. You gotta go up against Tennessee, Georgia, Florida, North Carolina, even Virginia with the Clipse. Within that tradition of Southern hip-hop, many of the cultural cues come from Houston. We’re still at the highest levels of hip-hop. So many people now do a chopped and screwed variation of an album. Then there’s the Latino representation, with artists like [That] Mexican OT, Bo Bundy, and Peso Peso.

Arguably the biggest, most impactful hip-hop artist on tour right now is Travis Scott. If you look at the crowd that he just had in Milan [for his Circus Maximus Tour], it was insane. That’s typically the kind of crowd you have for a music festival, where there are thirty different top acts. One guy tore that entire city to pieces. I’m loving this second wind of Travis Scott right now. He’s been exonerated from everything. He’s settled all his lawsuits. He’s made his amends. He’s back out on the road now with full confidence.

Megan Thee Stallion, she’s the female version of that, touring now internationally. It’s a great time to be from Texas. BigXthaPlug is showing that he’s having a ball out here living his best life. I’m proud to have ushered that in. It’s a beautiful thing.

All we ever wanted was a level playing field. We didn’t want any undue advantages. Let everybody start from the same place and we’ll show you they can’t fuck with us. It’s been beautiful to watch, but we don’t do it to just flex on people or for clout. It’s to contribute to the culture because we understand what the West Coast gave to hip-hop. We understand what the East Coast gave to hip-hop. We’re trying to make sure that everyone understands not only collectively what the South has given to hip-hop, but specifically what Texas has given and continues to contribute to the culture. I love having been at the forefront of that. I love being in a position that allows me to perpetuate further motion as well.

TC: When UGK was coming out, when Southern hip-hop was coming out, there was a lot of commentary about how Southerners can’t rap. People from Texas can’t rap. A lot of pop music credits André 3000 with announcing to the world that “the South got something to say.” However, UGK was releasing some of its best music before André’s statement at the 1995 Source Awards. How does that resonate with you?

BB: It was true. It was something that we all felt, but I don’t think any of us had been given a microphone and a platform in a room full of those people. That’s why the words resonated so strongly—not because of what he said, but where he said it.

They went up there all confident, and they literally were booed for having won with that album. There’s a stereotype of Southerners—outside of music and entertainment, just as people, as human beings—that we are lesser than. That we’re slower. That we’re still operating under some sort of slave mentality. But where do you think the civil rights movement started? The marches. Where people were getting rocks thrown at them and hoses and dogs turned on them. All of that happened in the South. We’ve been fighting oppression the entire time we’ve existed in the South. We’ve always operated from a space of cultural isolation. Even among other Black people.

It felt good to see someone get on a stage like that and be unabashedly Southern. I take nothing away from the impact of what André says. My job is to make sure I’m living up to it. We’d already been fighting that fight. We were already living up to it when those guys got there, but that only strengthened us. It also unified us because there was no taking it back at that point.

We got on the biggest stage, in the biggest room you could be in—New York, East Coast, however you want to designate it. André got up there and asserted our relevance and our eventual dominance. Those words still resonate with me today in everything I do, because even if it’s not music, even if it’s burgers, it’s still Southern. ![]()

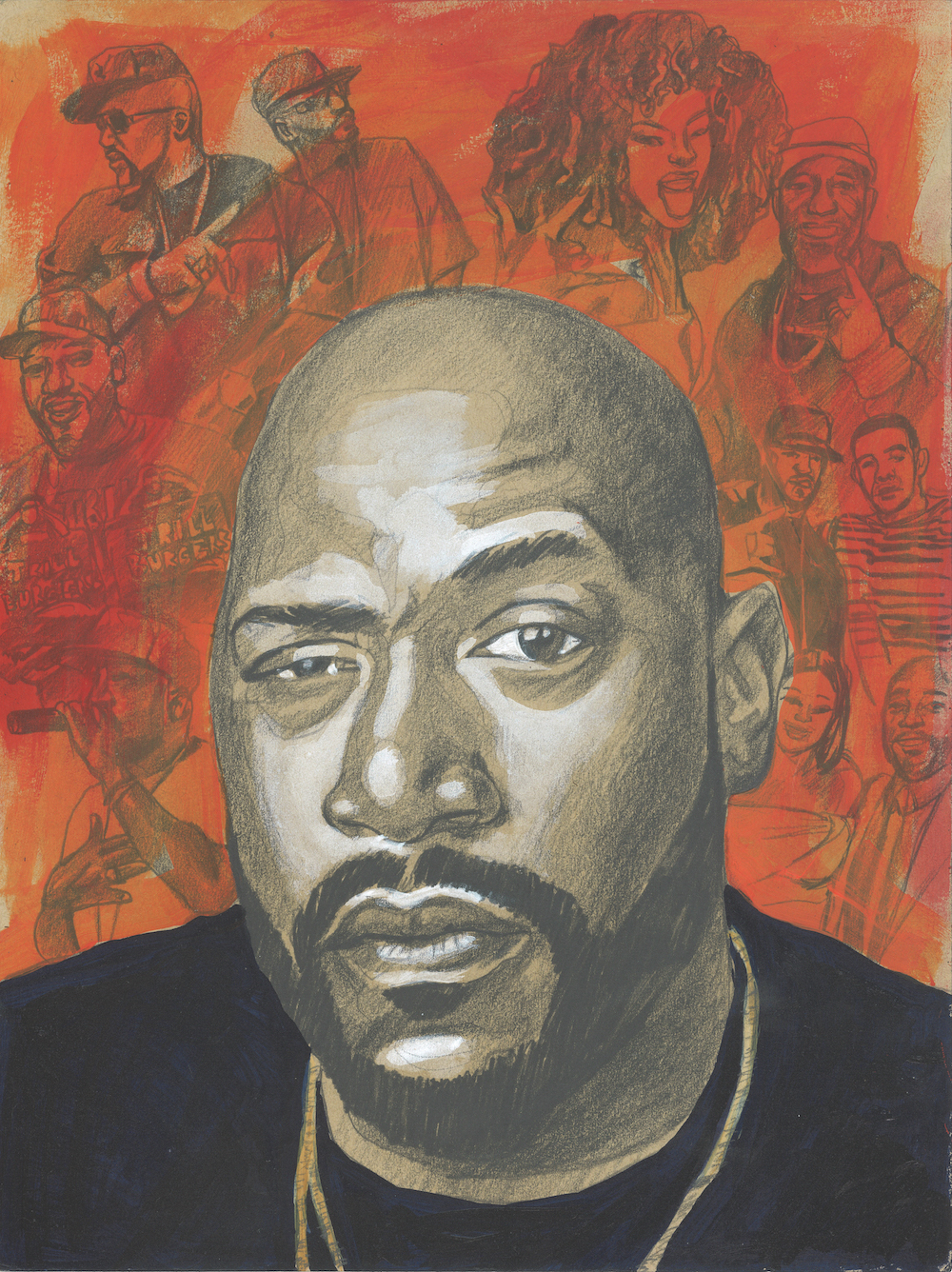

Bernard Freeman—better known to the world as Bun B—changed the hip-hop landscape as one half of the legendary UGK, alongside the late Pimp C. From their 1992 debut Too Hard to Swallow to their groundbreaking “Int’l Players Anthem (I Choose You)” with OutKast fifteen years later, the Underground Kingz made the South the center of hip-hop. While the Grammy-nominated duo collectively delivered six classic albums and two EPs, Bun solidified his solo-warrior status with five projects that embody his Port Arthur, Texas, mantra to keep it trill.

Taylor Crumpton is a music, pop culture, and politics writer from Dallas. She covers a range of topics, from Black queer advocacy to underrepresented hip-hop scenes in the US South to pop analysis of releases like “WAP” and “Black Is King.” Her work can be found in Time, where she writes a monthly column, as well as the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, Harper’s Bazaar, Essence, the Guardian, NPR, and many other platforms.

Illustration: Vitus Shell.