Know this: on the label of the box containing the definitive tapes, it says: “Bach / The Goldberg Variations / Glenn Gould.”

Listen: the aria that the thirty-one variations are based on is a saraband. A slow dance from the baroque period, an enigmatic and lyrical melody in two sections of equal specific weight and perfectly tuned atoms.

Each of the variations responds to the harmonic pattern of the original theme; for that reason, the bass line is similar for all of them. The first variation obeys the rules of a style known as an invention in two parts.

The second variation is, on the other hand, an invention in three parts, with the two higher parts conversing with modest pride over the bass that, for a moment, seems somewhat annoyed at not being the most exclusive center of attention.

Each of the three variations appears in canon, where the second of the two instrumental parts obeys and repeats with exactitude, almost obsequiously, the movements of the first at a distance of four seconds in time and space.

Less than a minute later, a briefer and more strident variation is introduced with four parts that fit, identical, one atop the next, like a line of exhausted lovers plummeting from the peaks of ecstasy.

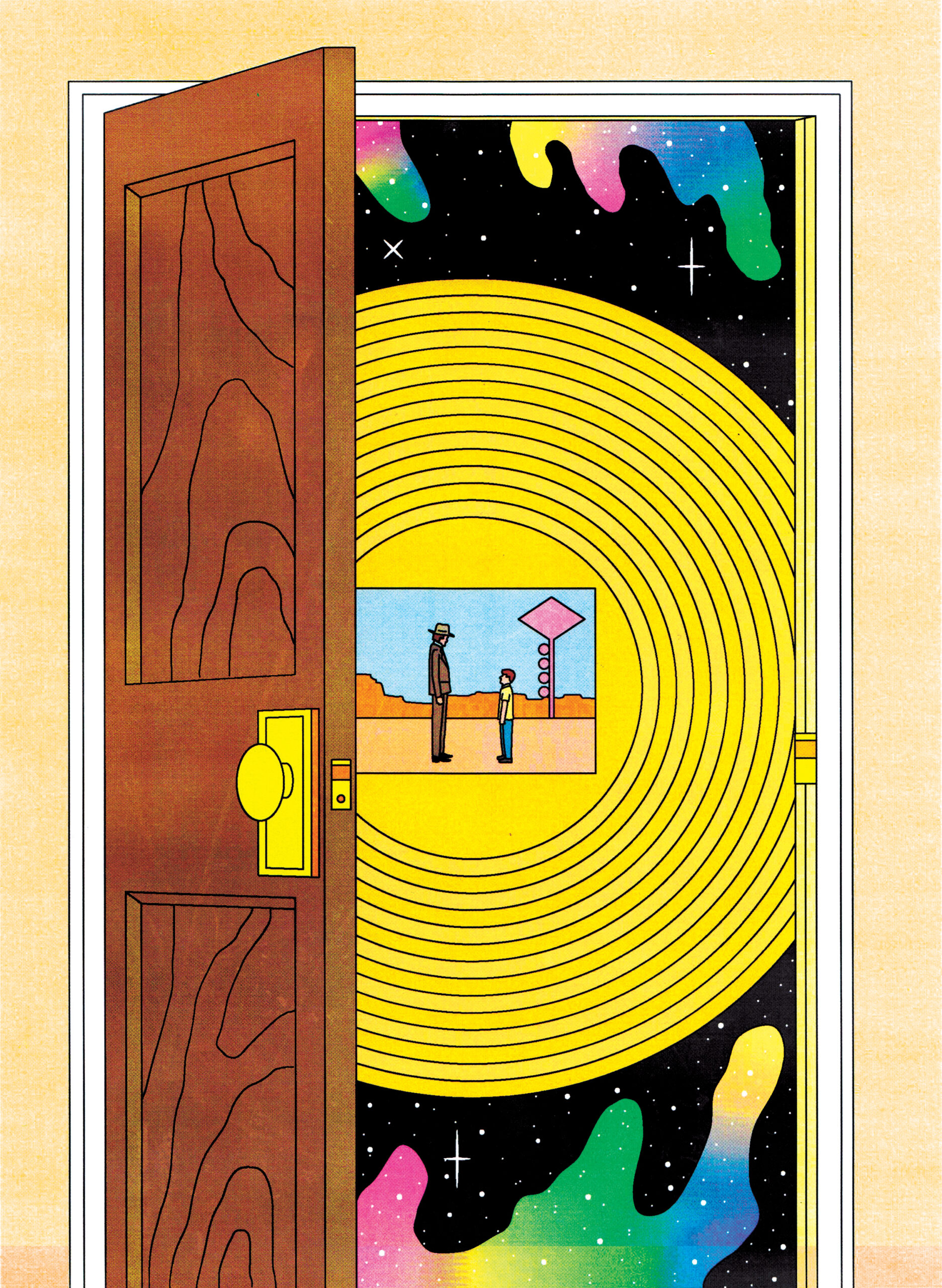

Then, surprising but never intrusive, an unexpected and poorly disguised variation of moto perpetuo comes knocking at the door, unfurling in whirls that converge toward the very center of the music.

I always play this last part with one hand. I recorded the Variations for the first time during the sweltering June of 1955 (me and my bench and my towels and my bottles of mineral water and my portable med kit) and yesterday I recorded them again, different, so many years later, in 1981, at the very same location: the old Presbyterian chapel that Columbia converted into a recording studio. On 30th Street in Manhattan. The “new” Variations—I like to think of the two versions as the Old and the New Testament of the same story—take up more space and include more of my murmuring. My tired voice, the discovery of slowness, meditation over action, the absence of any need to impress everyone, the wisdom of age and being near the end. It no longer makes any sense to run; better to walk, observe the sound of each variation with X-rays in the ears. Working them in segments. Recording them one by one. Taking them apart and putting them back together while being filmed for a documentary that (those in charge couldn’t have had a clue) would end up chronicling how the substance of one man is ready to be transformed into the ghost of the sound.

The high and low notes sometimes force me to make crosses and jumps of multiple octaves. Which is no problem. Highs and lows and crosses and jumps of multiple octaves, no matter—my hands glow in the dark, which makes all of it easier.

![]()

The sound of the numbers of the telephone rupturing the seal of the void of the night and your undoubtedly deserved rest, but, well, here I am again.

Hello. Hello. Hello. Is there anybody out there?

This is the unanticipated yet not entirely surprising call. The lonely runner strikes again, bouncing off satellites, accelerating its trajectory through the cables and posts and distant receivers of the world and the electric air that once was acoustic.

Here’s the voice, mysterious and hermitic and—nevertheless—friendly and trustworthy.

Here’s the Great Phone Bill and efficient foundation of the classic comment, of utterances like: “Good God, I bet you anything that’s G. G. calling again.”

Will you answer the call, my friend? Yes?

Listen, then.

Listen to the music I’m preparing to play on this instrument that isn’t a piano or a clavichord.

No: it’s a neurotic piano that insists on believing itself a clavichord.

![]()

Sometimes—more all the time, as the end of everything we know to be real approaches—I see unequivocal signs that Oppie isn’t dead, that he’ll appear like one of those jacks-in-the-box, popping out of the sharp-edged double bottom of a garishly colored box, out of an unknown corner of my tired memory.

But no, Oppie is dead.

As dead as the possibility of changing history, or of revising the formulas, or of reuniting what should’ve never been split.

An old postcard sent by Oppie, then. A consolation prize, something you find in a drawer when searching for anything else.

Look: on the postcard is Jesus Christ, standing beside an automobile driven by a couple of perfect adolescents. Beside the road is a highway sign with a two-headed arrow. Death, says one; Life, says the other. Jesus Christ, of course, points in the direction of life. Jesus Christ has one arm extended—the right arm (God is right-handed, the Devil is left-handed; ’twas ever thus)—pointing to the right and correct path, forward, the path the leads to life. Death is going in reverse; death is for cowards. Death writes terrible and definitive stories with his left claw.

On the other side of the postcard, under a stamp with the face of the master of lightning bolts, Benjamin Franklin, smiles the complicated handwriting of Oppie. The handwriting of someone more accustomed to the nervous and speedy tracing of scientific formulas than the cold and reflexive sketching of emotional formulas.

![]()

Read:

This man is a liar, G. G. Never trust individuals with beards and tunics who point out something for you on the side of the road. Never take candy from strangers (I made that mistake). Never experiment with certain dangerous elements. Never diverge from the advice and dictates of the instruction manual. Hallelujah!

This is just one of the many “Postcards with Christ” that Oppie sent me as soon as he was able to find me following the release of my first, famous recording of the Variations. Postcards that, when looked at against the light, reveal a transparent, never-entirely-formulated asking for forgiveness.

Now, a snapshot from a book that always makes me laugh. A photograph from 1938 of the scientist Otto Hahn writing something down on a notepad and Dr. Lise Meitner, between admiring and pious, observing him with that typical expression à la Marie Curie that all women interested in the secret laws that rule this planet seem to wear. The funny thing isn’t the photograph itself but what can be read beneath it: “Berlin, 1938: Otto Hahn discovers a phenomenon he can’t explain. Beside him, Lise Meitner explains to him that he just split the atom.”

Isn’t it funny?

It’s funny because it’s a lie.

Nobody split the atom.

Nobody will ever split the atom, for the simple reason that the atom doesn’t exist. Or, at least, it doesn’t exist as we imagine it.

The atom is a scientific and not holy spirit, an optical illusion that convinces mortals they understand something whose secret will remain forever hidden. But I’m getting ahead of myself, and this music requires a calmer tempo to be understood and enjoyed.

The old postcard, sweet Lise’s resigned eyes and, now, the famous photograph of Oppie circa 1958. Oppie frozen in the air, jumping for that photographer addicted to capturing celebrities in suspension, free for a few seconds from the inescapable imperatives of gravity. And Oppie’s words accompanying that photograph: “In the air, far from the ground, we’re all real; the truth appears, always, when there’s nothing to prop it up against.”

Oppie in the air, then: index finger pointed defiantly at the heavens and at everything that might hide on high. In the background, behind him, a chalkboard overflowing with formulas reminds us that, after all, Oppie has little to do with this world, with the ground we stand on every morning. Oppie and Oppie’s formulas prefer to concern themselves with light that travels here from very far away, from elsewhere, before concerning themselves with those of us who are but the shadow projected by that light as it collides with more or less solid matter, more or less true and real.

![]()

The wrath of the eye of God burning in Oppie’s eye.

New Mexico, 1945.

Remember the smile of X, the cry of Y, the absence of Z, the unexpected ghost of the music of Tchaikovsky (yes, it was I who amplified The Nutcracker suite seconds before the explosion) bursting from the speakers with playful joy, the words of Krishna legally adopted by Oppie on that successful dawning of what we subsequently knew would be called the Atomic Age:

“Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.” Oppie smiled as the furious forces of the Apocalypse lay down at his feet so he could stroke their spike-studded backs.

And then, that unrepeatable sound making its way from the depths of his throat. A sound as powerful as the one being cooked up there outside. The thunder of an orchestra of fire that seems to be braided together by its musicians into a kind of general rehearsal for the end of the world.

Who knows it if was the moan of the discovered sinner or the triumphant cry of the conquering beast? The truth is always in the eyes, and, of course, where are we to look for certainty or solace if none of us—perhaps out of shame—dares meet Oppie’s eyes? Our gazes were concealed by heavy goggles as black as the night that we would rend in five . . . four . . . three . . . two . . . one.

“Let there be light,” William L. Laurence, the obvious correspondent of the New York Times, would say that he whispered.

And, obviously, there was light.

![]()

J. Robert Oppenheimer was born April 22, 1904, in New York City. The J. of his name—despite the fact that some records insist it stands for Julius—doesn’t stand for anything in particular, doesn’t hide the shadow of another name that might have helped us understand him better. Nothing like that, and the truth is more deceptively simple: his father, a wealthy importer of textiles, maintained that, as a name, Robert Oppenheimer alone was not “sufficiently distinguished.”

I write from memory, and when my memory fails me, I flip again through an old issue of an old magazine: the aforementioned photograph of Oppie jumping and eight pages on Oppie interrupted—here and there—by ads for an all-terrain vehicle, for Bombay Dry Gin, for a selection of Jacuzzis, for the Concise Columbia Encyclopedia, for a voluminous, supposedly portable computer brought to you by one Isaac Asimov.

In any case and to entertain yourselves while I arrange the score of my memories, I here propose a brief exercise, splitting uranium (I believe this was the recipe of the lie): quickly bring together two portions of the element and the resulting mass will suffer a self-generated and spontaneous reaction. Implosion instead of explosion. Like squeezing an orange till you attain the devastation of the juice.

“Not very poetic . . . nim-nim-nim . . . but, well, after all, I’m not the writer. I have the small comfort of knowing that, at least, that responsibility will be yours and only yours, my dear pianist,” Oppie said smiling at me one 1945 morning in Los Alamos, New Mexico, while in the background a group of bandit musicians insisted that “ya no puede caminar, porque no tiene, porque le falta . . .” Oppie listened to them with a loving expression and kept right on humming his “nim-nim-nim”: the sound Oppie made when he wasn’t saying anything, when he thought nobody was listening. The sound of atomic energy in the engines of his thoughts.

The truth is that there were still five of the original nineteen months established by the ominous shadow of Colonel Groves before those supposed cabalists, between euphoric and frightened, barely protected by the arms of a magic pentagon, would unlock the door to the heavens.

I remember that we were always looking up, as if we wanted to escape from what was simmering on our horizon. And that there were only clouds and shapes of clouds so different from those whose names I’d easily memorized on the shores of Toronto, on the waters of Lake Simcoe, and what does that cloud look like, Oppie, what does it look like?

The clouds looked like so many things.

The clouds looked like:

—the hand of God on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel

—the silhouette of the Ethical Culture Fieldston School of New York where Oppie, on sweltering summer days, collapsed on his bed and read the dynamical theory of gases over and over again

—the smile of Jean Tatlock, his young suicidal lover who downed a bottle of sleeping pills and sank into the final waters of a Chicago bathtub (Oppie had abandoned her forever a few days before at the request of Colonel Groves. It’s not well regarded for scientists who work for the government to have relationships with beautiful militants of the Communist Party, the colonel said, explained, ordered.)

—the devastating fission of the hips of Kitty Oppenheimer, the monster wife of Los Alamos

—the unreturnable gaze behind dark glasses of someone I’ll settle for calling Jude

—a kind of gigantic mushroom, a corolla of light and fury growing like the wildest flower of a carnivorous plant ready to chew up the cosmos with naught but its petals

The ancient clouds of New Mexico resembled all those things and now, so much time later, my memory is a little like those clouds. The shape of my memory changes with the wind, and I have to rely on books and photographs that, please, must be preserved in lead boxes that can withstand a coming nuclear holocaust.

Sometimes, among the papers, I find a photograph—a photograph that shows me as I was back then—and I touch my white pupils and remember the reflex that made my eyelids twitch and I smile, once again, like when I was capable of smiling, like when I had a smile, like when my tongue savored the deservedly famous ultradry vodka martinis—“Never shaken, never stirred . . . nim-nim-nim . . . just so”—that Oppie prepared on special occasions.

In the photograph, I’m sitting on a ridiculous and rickety chair in front of a grand piano, my hands gloved, a scarf concealing a good part of my face, bundled up as if for a Russian winter, even though the inscription on the back of the photograph says it was actually “New York, summer 1943.”

Though the dates don’t align, though the perspective seems off, I am him; I am that pianist of messy temperament and impassioned fingers. Someone who once upon a time was new and young and debuted, proud, recording the most insomniac and forgotten and mysterious of scores.

I am the enlightened imbecile, the man who met J. Robert Oppenheimer one morning too perfect to be real on the lake of Planicie Banderita, in the ruins of Qumran, on the outskirts of Sad Songs, and very close to Trinity Camp, the site where the triangular eye of the Maker of All Things watched, between preoccupied and amused, an Oppie who liked to refer to himself as “the Unmaker of All Things.”

Then Oppie unstitching the sails of Creation and mutating into a mad wind. Oppie shielding himself behind walls of jokes because he knew he wasn’t doing what was right. Oppie knowing that success wouldn’t translate into a new beginning but into an infinite variation of approximations of endings leading up to the grandest and most perfect ending of all. That’s why he laughed. Because Oppie couldn’t fully hide it: the whitest of terrors was the force that drove all his foolhardy blasphemies, and so Oppie chose the name Trinity after randomly coming across, in one of Kitty’s books, that John Donne sonnet where it says “Batter my heart, three-person’d God . . .”

I remember that I too celebrated his humor; the wit of those insults braced the beams of his private holocaust. And perhaps that’s why events came crashing down on Oppie and on all of us, walking here and there, under that roof, with the cautious lightness of fakirs across beds of nails as we sang to the radioactivity of the body.

“Batter my heart . . .”

![]()

“. . . three person’d God. . .”—the voice of my mother (an astute music teacher) reciting John Donne aloud while my father’s violin fired off notes of lustrous mahogany from the throat of the stairway, upward, to the upstairs where my room and my first piano and the chair that would always accompany me are.

The most photographed chair in the history of music: a wood aberration, seatless, with legs sawed off to hold me up just fourteen inches above sea level, so that my hands hung off the keys like the hands of someone clinging to the edge of a bottomless precipice.

All of this takes place in a city that could well be called Toronto, but that has little to do with the official image reflected by tourist guides and maps.

I don’t know how old I am now. Calendars lost all meaning for me a while ago, and the dates above newspaper headlines seem like nothing but ridiculous and meaningless abstractions.

There are days when even my own name is hard for me to pin down, and then I resort to my disguises. Suits and wigs and voices and accents and absurd, caricatural personalities. I present myself like that in interviews or on TV shows. There’s no lack of people who accuse me of being a clown. But I laugh last in order to laugh best. Being other to not be myself. I transform into the Edwardian and antimodernist Sir Nigel Twitt-Thornwaite, into the sensitive Scot Duncan Haig-Guinness, into the German musicologist Karlheinz Klopweiser, into the infamous Bronx taxi driver Theodore Slutz; I make myself a mask until the pain of being G. G. rises back to the surface through the anesthesia of an alias.

But I do remember that during that summer of 1945, I was only thirteen, which didn’t stop me from moving with the pride of someone who thinks he knows exactly how the book of his days will end, someone who can’t help but read while standing among the shelves of a bookstore to keep from having to buy another biography.

Nothing turned out as I expected, of course. And yet, I’ll succumb to the temptation of drawing up a plan that never moved beyond the stage of paper and pencil, of ambitious sketch: my life, I was certain, would consist—like my favorite score—of two sections of equal specific weight.

The first section would go until the day I turned fifty.

Try to understand: I was just thirteen years old and had already signed in blood a document that committed me to living for and by the piano until I’d spent half a century on this planet. From then on—having lived half a century and fulfilled my commitment—I would swap the keyboard of a Steinway for the keyboard of a Remington and would devote myself to literature until the morning of my hundredth birthday.

That’s what I told Oppie that day on the lake of Planicie Banderita, and so it was that Oppie made me promise that the first thing I would write would be about those days at Trinity Camp.

It wasn’t entirely clear to me what would happen next; I’m not ashamed to admit here that I toyed with the idea of an unjustifiable immortality, a kind of lagoon frozen by winter across which I would glide, fast and without a care, on the sharp skates of the centuries.

Then I saw parts of my future (I could always do that) the way one attempts to comprehend the totality of a life by spying on the partialities of an unknown family in a photo album. I shut my eyes, and, once the darkness let in that yellow fog that filters through the eyelids, I fell into the contemplation of random pieces that would end up configuring the puzzle of my future existence.

I saw myself differently, with a face that flashed with the gleam of new eyes.

I saw myself entering what had once been a Presbyterian church, on Thirtieth Street of the East Side, in New York.

I saw myself bent over a piano the way someone bends—for love or for a crime—over someone else who is always the victim, and I heard Bach’s “Aria mit verschiedenen Veränderungen” rising with unsettling clarity from my fingertips.

I saw myself driving a heavy Lincoln Continental through the snows of the North, of the north with a capital N, an N that would never melt because up there the sun doesn’t warm but merely helps keep the cold in check, so it can’t keep descending from on high. An accumulation of tickets for “erratic driving of automobiles.” A patrol car follows me and catches me and the officer asks me if I’m OK. He tells me that I’m driving like a madman, that he saw me waving my arms and shrieking while the car changed lanes, ignoring all traffic signs. I tell him I’m sorry; I explain to him I wasn’t driving the car, I was driving the Schoenberg piece that just then was playing on the radio. (The Lincoln Continental—my fourth vehicle—would die the following year.)

I saw myself lit up like a holiday bridge. But with no water below my body. Just sand and wind and a sound, at once new and primordial, the sound of the beginning of all things.

I saw so many things.

I saw the photograph of the face of God. The photograph of a celestial body ten million times the size of the sun. The photograph of the aureole of God strolling through space with the same indolent confidence with which others walk their dogs. A circle of darkness as perfect and lonely as only God could be.

I saw then that God is alone up there and everywhere; I knew then that God was a place of such density that not even light could penetrate it.

I saw the exact moment in which the black hole of God devoured a galaxy just for the fun of it. God feeding on dead stars and correcting the borders of the map of His ever-expanding creation.

And so it was that, at sixteen, I collapsed on the keyboard of that piano with my head full of angel wings. Surrounded by a river of lights, my eyes straining to look to the heavens and my expression resembling the beatific gaze of saints with arrows protruding from their sides.

And so it was that I knew that God hadn’t finished His work, that His mood and His intentions were as changeable as those of the beings He’d invented, that He’d never made use of seventh day of rest and never intended to.

![]()

The family doctor opined then that the best thing would be to take a trip. Dry and distant climate and no pianos. That’s how we ended up in this hotel on the outskirts of Los Alamos, in a place called Sad Songs, where once upon a time there burned the wise and proud flame of respectable civilizations.

In the Sacred Hotel of All Earthly Saints there was no piano. The lobby and the lounge were nothing more than virgin spaces, complicated wooden rib cages holding aloft roofs that would burn and burn for multiple nights before too long.

There was no piano in the hotel in Sad Songs, close to Los Alamos. Thus the temptation of the solitary waters, to remember myself young and different, standing on the deck of a boat. In the very center of the Planicie Banderita lake, looking down into the depths of the waters and discovering the spinal column of the dam, sunk as if in a dream, there below, where you could also catch a glimpse of the streets and houses and gardens of a town buried forever by sheets of water.

The inhabitants of Sad Songs insisted on frightening me with ever-changing stories, stories altered according to the mood or stature of whoever was telling them, but coinciding on one inevitable point on a diffuse map.

Planicie Banderita was the place where the angels came; a holy place that when least expected would come up for air and spit out angels with sweet lyres or flaming swords—who knows—in their hands.

The thin man, they insisted, had arrived in Sad Songs to liberate the submarine servants of the Lord, to dry them out and return them to the heavens, where they belonged.

The thin man was none other than Oppie, or J. Robert Oppenheimer, architect of universal (and my own private) destruction.

The thin man found me now, standing in the exact nucleus of a mirror of water, arms outstretched and recalling, without moving my hands, the precise illustration of those variations, as if I were in front of my beloved piano, far away, north of all things, on the shores of another lake, a lake called Simcoe.

The secret was in invoking the tactile image of the music, of the entire work in question, and in locating in the cleanest corner of my brain to neutralize the boredom of my days and the medical prohibition to go anywhere near a piano.

That’s what I was doing—hands moving across the keys of air—when I heard someone applauding, and I opened my eyes and there was Oppie, in another boat, shouting: “Encore! Encore!” as the curtain of my shame rose and fell and rose again; as I went out to wave again and again, not knowing if it was the end of the concert or if it was, merely, those seconds of false silence that separate one variation from the next.

![]()

Organizing lives as if recording music.

Spending two or three hours in the studio to achieve—near fainting—the perfection of a couple minutes of redemption in the face of so much tunelessness, in the face of the infinite disorder of lives.

It took me a week to record the Variations the first time. I needed around twenty takes to locate—after so much searching—the true and secret character of the score.

I knew then that it was a matter of using the first twenty approximations as sketches of a profile that rebelled and revealed itself to me gradually.

I used the first twenty takes to eliminate all superfluous expression from my prior readings.

There’s nothing more difficult than this: but how can you renounce the reward that, in the end, yields the perfect knowledge of the aria da capo; how can you resist the complete understanding of its movements and mutations?

I’m attempting the same thing now with Oppie, but, of course, I’m no longer the same person, and I move in circles around these Oppenheimer Variationen with the mistrust and privilege of one who knows himself the lone survivor in the story.

Thus I organized and reorganized Oppie the way one throws—furiously into the sky—the body of a symphony just for the pleasure of seeing how it comes crashing down into the orchestra pit.

J. Robert Oppenheimer precipitating into history.

J. Robert Oppenheimer, the tall and thin man who brushes his hair with a dog brush. Blue eyes and walking invertebrate down the main street of Sad Songs. J. Robert Oppenheimer looks a little like James Stewart, advancing with the determination of someone who knows what’s in front of him is not necessarily there and who, for that reason, seems to move in all directions at the same time, like a wayward molecule.

J. Robert Oppenheimer learning languages so he could read texts in their original. He learned Italian to read Dante; it took him less than a month. Just before turning thirty, he conquered Sanskrit so he could read the Bhagavad Gita as it had been formulated. And yet, in each and every one of the languages that he learned to make his own, he interposed an unmistakably Oppenheimer particle: the nim-nim-nim that already appeared in these pages and danced in the spaces between all phrases, turning any foreign language into a particular dialect. Nim-nim-nim like a kind of mantra, like a password that could open any escape hatch.

J. Robert Oppenheimer driving an automobile with a female student beside him too beautiful to be real, shuts off the engine somewhere in the Berkeley Hills. He needs some air, he says. He walks around and around the vehicle and begins to swim in the dark waters of a physics problem. He thinks and walks and drifts and suddenly abandons his orbit and moves off through the entrails of a forest, down a path that leads to the deserted dance studio of the Berkeley Club. Numbers and symbols dance in his head and, pitiless, decide to follow him in his dreams when he collapses on his bed and the car and the girl have been left so far behind and so far away. J. Robert Oppenheimer dreams he solves that problem in the exact moment that two police officers find a young female student crying inconsolably in an abandoned car, somewhere in the Berkeley Hills.

And Oppie never believed in coincidences. Why think, then, that our encounter in Sad Songs was but a chance tremor? Over time, I began to see the two of us as different parts of the same equation, like the alpha and the omega of a singular structure. It’s under this principal and this belief that I take up a tepid defense of your actions, Oppie. The truth is that your organism wasn’t born for failure; you thought you couldn’t resist it. I’m not so sure. In that, I think, we were so different, yet so complementary . . .

I still keep a—another—photograph of me taken a few months after my birth: there I am, in the cradle, arms outstretched, fingers in perpetual motion: “The boy will be a great pianist. Or a great physicist,” the family doctor said. And I, perhaps sensing that the place for the laws of physics in this story would be occupied by another character, began to fix my eyes on that black and vertical contraption standing against the wall of the room on the shores of Lake Simcoe.

The old battle between art and science, dear Oppie.

I always maintained that the definitive objective of art was the deliberate construction of perfect wonder and serenity.

Its immediate purpose (I wrote in some distant notebook) would essentially be therapeutic, until it attained the possibility that art itself, as a form, would disappear in space. Because it’s for the wise, I think, to accept the idea that art has no reason to inevitably be benign, that inevitably there is a nucleus of chaos and destruction behind so much beauty. That’s why we must analyze the different areas that cause the least damage to humanity and use them as guides. That’s why art is the instrument humanity has created, almost without realizing it, to defend itself.

And the same thing holds true for the exact sciences.

But, of course, you were moving through a blinding storm of chalkboards, uniforms, and formulas while, on the other side of things, the war in the Old World functioned in your theorem like the least serene of inspiring muses.

We were so different and at the same time perfectly in tune for the development of a story that would change art and science and death.

That’s why we were chosen.

That’s why, with Jude’s arrival in Sad Songs, the alignment of the triangle was perfect, and all that was left was to sit down to await the inevitable with the innocence of one who contemplates those skies of the North brimming with aurora borealis.

That’s why everything ended the way it ended.

That’s why you ended up like this, occupying a place in this story.

That’s why I chose the shadows, and ever since, since those days in Sad Songs, the main objective of my nights has been to try to turn myself into the perfect prisoner.

The perfect prisoner—know this—is the one condemned for crimes he never committed. I don’t think there’s a better way to flagellate the flesh, and I’m sure there’s no more meaningful mise en scene against which to project the life of the recluse, which, paradoxically, is what has made me famous above and beyond my musical aptitudes.

My dear Oppie, having exposed myself to the explosion of your false bomb and the truth of a story, I’m not much interested in strolling across the predictable surface, across the lowlands of stages and auditoriums littered with identical beings.

Just months after leaving Sad Songs, I threw myself with passion into becoming, for all other mortals, an unpredictable madman. A wild genius who would shine for a few years with the splendor of a supernova and then disappear behind the consoles and darkness of the fishbowls of recording studios, sanctuaries where I would move with the intuitive elegance of deep-sea fish that have never seen the light of the sun.

Thus, my search for a hagiography of my own has been successful.

Thus, I now attain the perfection I always wanted for the end of my days on this planet.

![]()

With each night that passes, the dream comes in brighter colors, in better-performed variations.

I dream of Johann Sebastian Bach in 1741, traveling from Leipzig to a Dresden that no longer exists.

Bach has come to visit one of his young disciples, Johann Gottlieb Goldberg, an employee of Count Hermann Karl von Keyserling, Russian ambassador to the court of Saxony.

I dream of the famous neuralgias of Count Keyserling, of pain that keeps him from sleeping at night, of his desperate plea that Bach compose a piece of music to help him bear the passing of the sleepless hours and the shadows.

Bach selects as theme a brief saraband that he’d sketched out years before in Notenbuch that he gifted to his young second wife, Anna Magdalena. Count Keyserling is grateful and pays Bach with one hundred louis d’or, the best compensation the composer ever received.

I dream of the suffering count—his eyes always open like certain nocturnal birds—begging his servant in a whisper and with an exhausted smile to “Please, my dear Goldberg, come play my ‘Aria mit verschiedenen Veränderungen.’”

![]()

I dream of Oppie begging me, “Please, my dear G. G., come play some of those damned Variations.”

The piano in the Los Alamos house, the bitch-in-heat glances of Kitty Oppenheimer, the mutinous desperation of the subordinates, and Oppie going mad in slow motion. Everything is secret and nothing turns out as it’s supposed to and, why not create a uniform? Oppie puts it on and shows it to me and marches through the living room striking the heels of his boots against the hardwood floor. A half turn and a Nazi salute and a hysterical crisis and me running back to the Sacred Hotel of All Earthly Saints with Oppie’s cries echoing in every direction: “They want me to discover the method and to manufacture the weapon to disarm the world! If I pull it off, I’ll be a hero, I’ll be part of the history of humanity! They want me to part the waters of the Red Sea again!”

What Oppie couldn’t understand, what was driving him mad, was not knowing why they had chosen him. Nobody better than me to understand his desperation, because I too had been chosen for reasons that to this day I still don’t know.

I’d been born with the gift of understanding the breathing of all music.

I’d never studied for hours and hours in front of the keyboard; I was unfamiliar with the pleasurable torment of discipline by which the hands of the best pianists had been hardened.

I lived hounded by the cold of knowing myself to be the best without having set out to become the best. A cold that seeped into your bones and blood and never let you sweat out the satisfaction of a job well done. Thus the gloves and scarves and hats under the suns of Sad Songs, of Quebec, of Washington D.C., of Nassau.

Thus, my madness leaned on his, and soon they stretched out through the whole encampment, through the dirt roads and prefabricated shacks and the minds of the most intelligent men of their generation, functioning as simultaneous dynamos, their friction firing off sparks in the darkness.

Today, so much time later, that same madness had spread across the world like a nefarious gas.

Thus, I read that the longest piano marathon featured a fool named David Scott who played without stopping for fifty days and eighteen hours.

Thus, the first postwar atomic experiment took place on June 1 on Bikini Atoll. It laid waste to a float of seventy-five warships populated by an army of 4,800 goats, pigs, and rats. The device dropped on the ships was decorated with a portrait of the actress Rita Hayworth and answered to the name Gilda.

But the device wasn’t the direct cause of the column of fire, the raging wind, the inappropriately red sky. The one truly responsible was an individual named Jude, someone even the most skeptical would mistake for that man on all the crucifixes without hesitation. It was him, yes. This was something and he was someone only I—now that Oppie is no longer among the living—know.

And a day doesn’t pass without me reading in the papers new irrefutable proof of the foolishness of man, a direct result of what happened that morning at Trinity Camp, on the outskirts of Sad Songs.

So it is, Oppie: no jury would pardon us.

Because we—apparently ingenious individuals—also possessed the most ingenious of stupidities.

For that reason, the stupidity of others deserves little space here.

I’ll just mention in passing the words of a psychoanalyst who didn’t hesitate to link my murmurs on my records to a desperate need to remove the reality of the outside world from inside me. I won’t pause either on the blindness of all those who didn’t know how to share the ecstasy I felt on the stages of the world and who settled, due to said blindness, for condemning the gestures I made in front of keyboard. I prefer, on the other hand, to refer to another kind of stupidity: a more complex and fascinating stupidity.

The stupidity of that man who—captivated by the Mona Lisa—contracted the best copyist to paint a perfect reproduction and, before long, couldn’t help but feel that the copy was better than the original. Years later, minutes before his death, the man smiles for the last time at that painting on the wall: he smiles his infinite gratitude because, oh, what do those fools know who day after day drag themselves in to stare at a crude reproduction in the Louvre. His Mona Lisa has always been the real one; the other one is merely an enthralling mass phenomenon, the hysteria of collective delusion.

A tiny yet definitive detail separates the story of this man from that of Oppie. The man who loved the Mona Lisa dies happy and convinced of the truth of his lie. J. Robert Oppenheimer, on the other hand, died slowly and in torment. The slow arrow of a cancer took years to pierce his throat and by the time—February 18, 1967—he closed his eyes forever in the cell of a cloistered monastery, Oppie was already far from being a man convinced of his madness and further still from having found the solace of God.

In his last letters, he wrote to me that he liked to play poker on Fridays, that he had perfected his recipe of eggs à la Opje (green chili and scrambled eggs); that he’d sold his sailboat Trimethy and given away his Mexican ranch Perro Caliente; that he didn’t miss women but did miss the act of buying gardenias for women; that he never missed a single episode of Perry Mason; and that “no, my dear G. G., I haven’t found nor do I believe it possible to find”—invoking one of his favorite quotes—“that thing about the gift of the peace that the world cannot give.”

![]() What comes next is the truth: this is the true smile of the Mona Lisa, this is the true protagonist of this story, someone—for reasons of convenience, to keep from complicating the pentagrams with far more complex melodies—we’ll just call Jude.

What comes next is the truth: this is the true smile of the Mona Lisa, this is the true protagonist of this story, someone—for reasons of convenience, to keep from complicating the pentagrams with far more complex melodies—we’ll just call Jude.

His physical appearance and his face—for the same already cited reasons—will be quickly described: Jude bears an incredible resemblance to Jesus Christ, though he’s a bit shorter than any believer would dare imagine Jesus Christ. And his face doesn’t possess the delicacy that one learns to find in prayer cards and effigies baptized generally under hoses and fire extinguishers spraying tons of holy water on the ceilings of industrial vessels bigger than cargo ships.

Here’s the photograph: Oppie and Jude and me standing beside the bombs that would soon travel uninvited, one to a city called Hiroshima and another to a city called Nagasaki.

There we are, Oppie and Jude and I and two useless and harmless devices called Fat Man and Little Boy.

Harmless because the atom doesn’t exist, the atom cannot be split.

Listen: Jude has come to Sad Songs, dragging his damned suitcase and his damned curse, and it’s no coincidence that he finds easy complicity in Oppie’s desperation.

Before long, Jude is moving through Trinity Camp like he owns the place.

Before long, he offers Oppie something that Oppie is in no condition to refuse and that I’ll mention here at top speed, as if performing the most trivial of left-hand exercises or one of the quickest variations, the one that strikes me now as the ideal soundtrack for the most terrible of silent movies.

On the screen, I now imagine the face of an actor who gesticulates excessively though needlessly, because, well, the actor has achieved a near impeccable personification of Jesus Christ and then he looks at the camera and moves his lips and the black cardboard with white letters explains then that what he said is:

“Oh, man is not master of supreme knowledge. He doesn’t know how the things of this world began, much less the instructions for their destruction. That which all of you insist on believing in, as if you were blind from birth and have been lied to about the true nature of colors; what you call ‘physics’ and ‘chemistry,’ is nothing but the clumsy hypnosis of believing yourselves masters of your own destinies . . .”

The actor who plays Oppie falls to his knees and receives the blows of the stones of this speech while desperately hiding his face behind his hands. Suddenly, he looks up and asks:

“What’s to be done then? What’s the secret?”

The man who bears an unbelievable resemblance to Jesus Christ responds with a slow smile:

“There’s no secret . . . your research is doomed to fail . . . and yet . . .”

“Yes?”

“I can offer you something.”

Expression between supplicating and incredulous on Oppie’s face.

New card, more text:

“What I can offer you, because such is my power, is that every time one of those useless devices that have been built and assembled according to your instructions is dropped, something will happen . . . what I can offer you is that, then, on each and every one of those occasions and by my will, man will bear witness to a minor apocalypse. A hurricane of death so powerful that it will make your faith in the Creator waver and grow at the same time. What I can offer is for you to go down in history as the man who fabricated the key to a door that should never have been opened.”

Then the image fades to black; but before the darkness is total, I ask that you notice that small figure who is spying on all the action through the blinds of a window.

Yes, that’s me. That’s the man who saw too many things too soon in life. That’s the boy I once was and who from that moment on I’ve never been allowed to be again.

From that moment on, everything was like a story whose resolution came crashing down on everyone without giving us any time to catch it in our arms.

Thus the “aaahs” and “ooohs” of the audience who, secretly, always wanted everything to end exactly like this.

Thus—just forty-eight hours after the agreement—the first explosion.

Thus, then, soon thereafter, Oppie waving from a convertible that advances in slow motion through the jubilant streets of Sad Songs.

Thus—claiming a deep and inexplicable melancholy—I begged my parents to take me back to our house on the shores of Lake Simcoe as soon as possible. To the cold of the North that justified my excessive winter clothing and the methodology of my pills and medicines to never cure me of my hypochondria. Returning to the routine of a score that my perfect ear and photographic memory would soon turn into something as familiar as the arrangement of the rooms and the trees in a place whose behavior I could still understand and enjoy as if I’d composed and performed it; to allow myself to turn off the lights of my auditorium at sunrise on the seventh day.

![]()

I was born in Toronto, and this city has been my general headquarters all my life. I don’t really know why; fundamentally, I guess, it’s a matter of security. I’m safe here. I’m far away from everything here. Toronto is one of the few cities that I say I know and the only one that seems to offer—at least, for me—peace of spirit. In my youth, I remember, Toronto was known as “the City of Churches” and, in effect, the most vivid memories of my childhood related to Toronto have to do with the churches. With religious services on Sunday afternoons. With the afternoon light filtering in through stained-glass windows, coloring the air. With priests who always—this is what Oppie was referring to in his last letter—concluded their farewell blessing with a “Lord, grant us the gift of the peace that the world cannot give.” You see: Monday mornings signified the return to school and having to face all kinds of terrifying situations. I was already a freak, already not like everyone else. So those moments of refuge on Sundays, in the afternoons, became something very special and sacred. They meant that, in that place, I could find a modicum of calm and stillness. And I guess I should confess that I don’t go to church anymore, but I do remember and often repeat that line about the gift of the peace that the world cannot give. And I still find great comfort in it. I say it over and over, throughout the day. I say it when I get up and when I go to bed. I say it when I open my piano and when I close it.

![]()

The sole purpose of a door that opens is knowing that someday it will close again.

My first recording of the Variations, in 1955, functions as an enthusiastic “Here I am—I have arrived, and history begins with me!” It turns out to be perfectly coherent—overcoming the astonishment of all those who considered that old recording definitive—for me to return to the same notes, to the same studio, twenty-seven years later, to leave a recording of the sound of the door as it closes, the “Farewell and thank you for listening!”

I knew then that the end was nigh.

A few weeks before the first recording sessions, I began to lose the ability to project myself into the future, receiving chronic headaches in exchange. No. That’s not how it went, and soon I knew it: it was just that I didn’t have any future left. The tape of my days was spinning its final spins and approaching the void, because there was no place left for it to keep recording.

I went back into studios as I had so many other times: the obvious invisible man enveloped in scarves, hat, jacket, and gloved hands, dragging his famous and disfigured chair. Someone took a picture of the empty chair beside the piano and that photograph was the last spasm of the future I was allowed to see. I knew that that photograph would appear among the back-cover notes to a record full of obvious funerary gestures and transparent farewells.

The cover would be printed before my disappearance, and yet, go and look and you will find clear symptoms on the back: empty chair without G. G.; the de rigueur text framed in the black bands typical of obituaries, and, in each groove, my oft-criticized murmurs and sighs leaning on the notes of the piano. Only the most insensitive would miss the fact that, yes, I was saying goodbye between the measures of the aria that closes the miracle.

I know that several of the sound engineers and a handful of my best friends couldn’t keep from weeping as they heard me perform the Variations for the last time.

It embarrasses me to acknowledge that I too wept in my own way, that I was happier than I’d ever been, because there were no longer any doubts; there was nothing left before me. That afternoon, I played the Variations like someone locking a drawer and throwing the key into the waters of a lake and walking slowly away to a place where he’ll finally be able to rest, alone. They asked me once if, given the opportunity, I would have devoted myself to another profession. I said I might have liked to be a prisoner serving a life sentence, but, for sure, one who was innocent of all the crimes for which he’d been locked up.

Think of my life as the story of a man who decided to turn himself into his own landscape. When a man transforms himself into the only possible landscape of himself is when he attains the sacred form of solitude.

I had arrived, yes, at that place where all the saints are alone.

I had arrived.

![]()

This is the end of all my things, the exact point when my known universe reaches its point of maximum expansion and—with a resigned sigh—begins taking its first, tentative steps back, beating the most placid of retreats, and, oh, the solace of knowing that there’s no beyond, that what’s ahead has ceased to be a viable option.

And so I call you on the phone at the most intangible hours of the night; I call the few people who will know how to listen and unload the trucks of my memory, here and there, in strategic locations, with people who will know how to remember and to remember me.

Yes, G. G. again—is there anybody out there? G. G. knocking three times on the polished surface, on the ebony and oak of friendships that I put to the test again, now, with minutes of telephonic pulses piling up, as if obeying the dictates of a metronome. Sure, it’s late and you were sleeping the sleep of the just or of the unconscious, but, oh, it’s me and I have such marvelous tales to tell . . .

So I’ll talk till sunrise, till sleep comes, and with sleep, the visions, the scenes of a film never shot yet perfectly comprehensible.

![]()

I find myself in the final measures of this story. Here I move to the end of my life and then, yes, a hand to protect my sun-weary eyes.

And I see:

A gravestone covered in snow. My name. Two dates separated by fifty years. The silhouette of a piano sculpted in dark granite and above it the opening measures of the aria da capo.

Further still: the climactic changes impossible for any meteorological forecast to detect. Incoherencies in pressures and temperatures and the genesis of a red storm in my brain. A dry and terminal wind.

I collapse a week after reaching a half century of life. Not one novel written, but the solace of these pages and the kilometers of recordings that I once considered erasing on the shores of Lake Simcoe, in the sympathetic shadow of my first piano.

The ambulance, the hospital, and my refusal to have any of it made public, my progressive decline into unconsciousness, my automatic understanding of the slow-motion music of death. I discover that I play it well, slowly, with elegance, and that there are no witnesses—nobody criticizes my song now as I play it with the calm of singing for nobody else, for me alone. At times my voice obscures the music, but there’s nobody here to point it out.

Then comes the color gray, my favorite color, and the flatline of my brain, which (pious and ever concerned with dramatic timing) allows itself a surprising gesture to close and reinforce my humble legend, a final glimmer of sanity.

I open my eyes and find myself, almost surprised, in a hospital bed, surrounded by those closest to me. Someone is weeping at my fate. How to describe the final pleasure of seeing all of them, half marveling and half terrified at my recovered smile? I sit up in the bed without difficulty. I look at each of them in turn; I look at them slowly, but with the same speed with which at other times I would memorize hundreds of notes in a matter of minutes. Then I say goodbye. Like this: I raise my arms to direct the transition of an orchestra that only I can hear.

That’s it: music and a dream come true after all.

I see myself from overhead; I see how they cover me with a white sheet, with the same respectful parsimony with which I shut the tops of so many pianos at the end of so many concerts. Salzburg, Jerusalem, Moscow.

Later, as I ascend, everything seems to become disordered. It doesn’t take me long to realize that this is due to the implicit chaos of the world of the living.

Then I move away and suddenly it’s space. The blue and black and cold that I never knew; the certainty of having attained the most impregnable of solitudes.

I float toward the light of my funerals in the Toronto Cathedral. I was always curious to know who would come to my funeral. Now I know.

I float toward a light similar to that of the churches of my childhood when it was me and the organ and the music and the true possibility of an all-knowing God.

Look: there’s an artifact drifting through space that for once doesn’t seem to tempt me with the vision of a waiting keyboard. Then I remember.

A golden record. An invitation dance.

I remember that they showed me pictures and read to me that thing about how “This is a present from a small, distant world . . . ”—a line that the voice of the president of the moment wouldn’t take long to record. Voyager 1 and 2.

I remember that a functionary told me (with a pride that at the time I couldn’t comprehend but that now strikes me as obvious) that Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 were designed to hold up to the erosion of nothingness for more than a billion years; that their preestablished trajectories would take them beyond Jupiter and Saturn and Pluto; that they would leave the map of the known solar system between 1987 and 1989, and that from there onward, the first would head toward the clear eye of the Ophiuchus constellation and the second would hone in on the spritely domes of the Capricornus constellation.

A golden record where—listen—the figures of a man and woman appear alongside greetings in Sumerian, in English, in all languages, but leaving space for a compendium of the sounds of this planet that I’ll soon abandon. The moans of whales; the irrepressible joy of volcanos; dogs and trains and trains barking at dogs; laughter and kisses and the forgivable obviousness of Louis Armstrong’s “Melancholy Blues”; a Japanese flute describing the dance of the cranes in their nests; the Queen of the Night aria from The Magic Flute; pygmy girls from Zaire offering up a colossal rhythm of initiation.

And me in front of a piano, in a recording studio that was once a church elevated into the heavens for the glory of Our Lord while I can’t help but wonder who might have forgotten to add, whose decision it was to omit, the definitive sound of that first atomic morning in Trinity Camp, on the outskirts of Sad Songs.

Near the end of the golden record, the Prelude and Fugue in C, No. 1, from the first book of Das Wohltemperierte Klavier. Bach performed by G. G. and—now I understand all of it—what better than a fugue as a passport for this long journey? A fugue is the process that only has to do with itself, that isn’t capable of any evolution beyond its own orbit and that, without coming to any conclusion, is an infinite process.

If all goes well, within forty thousand light years, both artifacts will approach the edges of a magnitude 4 star. AC + 79 388 will be its name, and if nothing happens there—if I don’t find an auditorium ready to appreciate my music instead of rejoicing at my . . . uh . . . eccentricities—I’ll continue onward, traveling to AC-14 / 1833-183 or perhaps to DM + 11 / 651 or to Urkh 24, where the memories of that sun shining on the waters of Lake Simcoe, of the wind sweeping away any possibility of a postcard, of the flower of death falsely adjudicated to the desperation of J. Robert Oppenheimer will merely be invisible notes in the infinite complexity of a concert that—at last—only I’ll be able to understand after millennia of concentration and discipline.

I’ll study it every night knowing that here there are only nights and that time doesn’t matter.

I’ll study for the first time because, here, I’ll know nothing; the notes will be other and the keyboard will answer to different laws, and I’ll be happy because—after so much time—I’ll be offered the possibility of a melody that I don’t understand and that I need to understand.

I’ll study, yes, until I see all of it.

Only God sees all things; but I’ll be ever closer to God and I’ll only miss, maybe, singing Mahler to the elephants at the Toronto Zoo, to the fish in Lake Simcoe.

And at some point, in the perfection of an instant, the author of all music will come searching for the music hidden in that artifact and will have no trouble at all interpreting the instructions for making that golden record play.

Then I and the music will be one in your ears as you comprehend that my passage through this story has, in the end, had some meaning, that from out of the chaos of my days comes the solace of a melody that’s simple and light yet not for that reason easy to condemn to the oblivion of time. ![]()

Rodrigo Fresán was born in Buenos Aires in 1963 and has lived in Barcelona since 1999. He is the author of thirteen books of fiction, six of which are available in English: Kensington Gardens (2005), The Bottom of the Sky (2018), The Invented Part (2017; Best Translated Book Award 2018), The Dreamed Part (2019), The Remembered Part (2022), and Melvill (2024). Fresán was awarded the Prix Roger Caillois in France in 2017 for his entire body of work.

Will Vanderhyden has translated more than ten books of fiction from Spanish. His translation of The Invented Part by Rodrigo Fresán won the 2018 Best Translated Book Award. Vanderhyden’s work has appeared in such journals as Granta, the Paris Review, Two Lines, Future Tense, and Southwest Review, and he has received translation fellowships from the NEA.

“Music to Destroy Worlds (An Experiment)” first appeared in Spanish in the collection Vidas de santos (Planeta Argentina, 1993).

Illustration: George Wylesol.