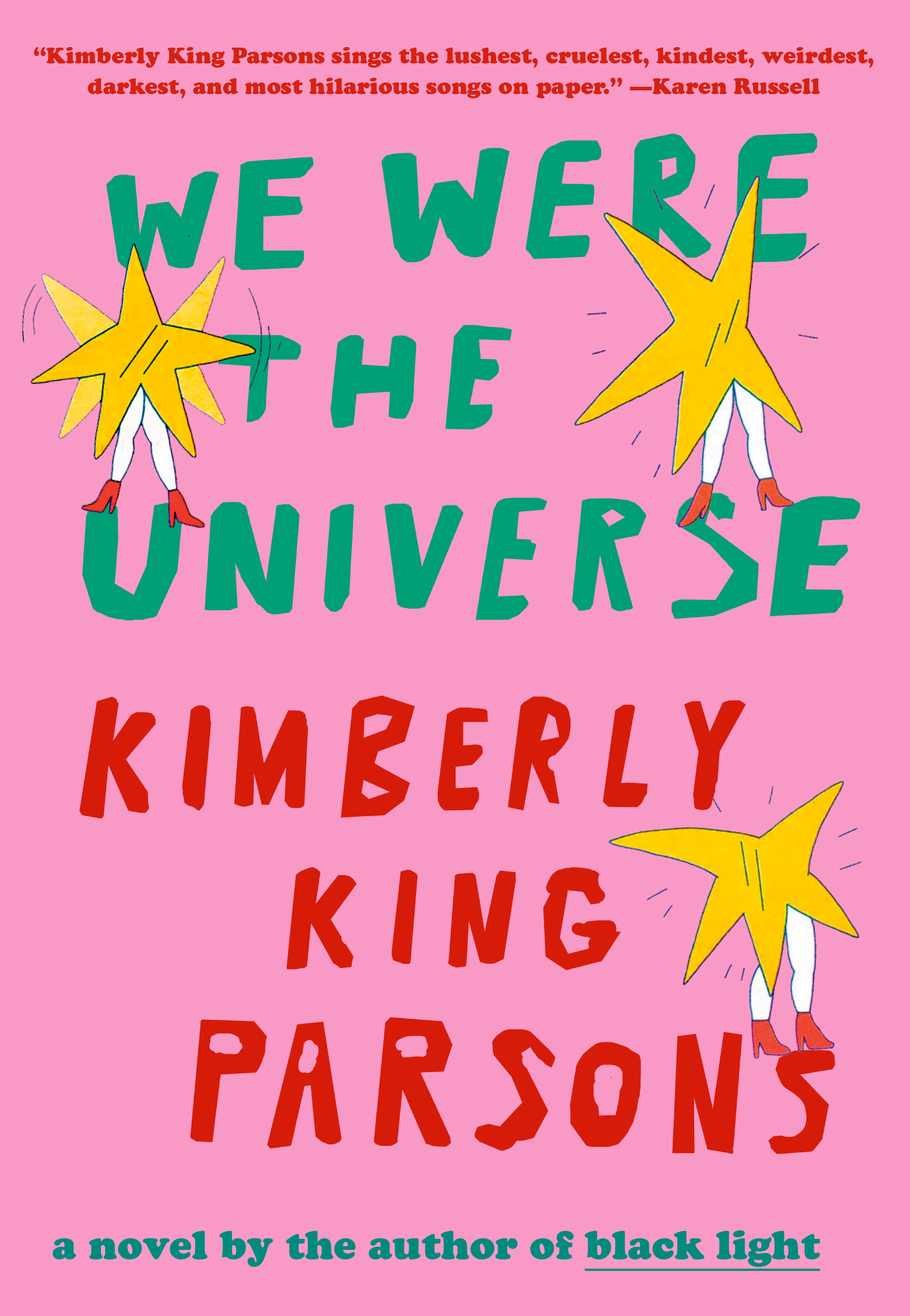

Lloronas went onstage around 1 a.m., January 1, 2020, a loaded hour in retrospect, which at the time felt dizzying and full of promise; a new decade was upon us, and I was tipsy in a cheap Penny Lane coat. Punk rock pulsed from the small stage of Slackers, a club on San Antonio’s St. Mary’s Strip. The women of Lloronas seduced me with their playful rage, and for a few moments I was only a body being emptied of its worries. There is a reason rock and roll keeps company with sex and drugs: they allow us to disassociate into something loose and transcendent. In her debut novel, Kimberly King Parsons departs from the usual beats of band literature: in We Were the Universe, we see that the most punk rock act is failure. This is a story of a band and its ashes.

We Were the Universe hinges on a constant exchange of energy, as characters drain each other of all they have to give. New moms melt on park benches, watching their children under the heat of the Texas sun; a dead sibling haunts her living sister on phone lines, in hotel rooms, at the grocery store; a withholding mother hoards newspapers and trinkets and waits for others to clean up the mess. There is piss and lactation and decay; motherhood, it turns out, is very punk.

The narrator, Kit, is marooned in North Texas suburbia, a young mom (by millennial standards at least) still mourning the death of her younger sister, Julie, who died three years prior. She spends her days in the throes of motherhood’s demanding monotony, taking her daughter Gilda to this playground and that playground, watching her toddler gymnastics class, wiping down her sticky skin. Though drained, she knows her audience needs more: “Nobody wants a mother too sad to make a sandwich, a wife too crazy to fuck, a friend who sounds insane.” Kit is restless and misses psychedelics and casual fucking, but is too invested in her commitment to “good” motherhood and to monogamy to indulge. Her mind drifts to her youth in a desolate small town in West Texas where she once tripped with Julie and her friends, melting into a pink carpet on a trailer floor, and where today her mother has neglected her childhood home to the point of condemnation.

Kit, though perhaps not warm and fuzzy, is palpably self-aware and refreshingly frank. Parsons balances Kit’s ravenous interiority and trauma with a languid pacing. A sense of friction and disorientation is born from this daily, hourly tracking of a week’s time. Are we still here in this park, this pool, this bed? Like Kit, we squirm.

We learn that Julie is one of those imploding stars, burning so bright before collapsing into her own chaos. A dying star that remains uncharted, she leaves a gaping hole in space while disrupting the orbit of entities in her wake. Kit describes Julie as “waifish and greasy haired with a smile that could crack the world apart” and “a voice that triggered devotion.” The name of their band is You Are the Universe, and during live shows Kit and their best friend Yes share glances of anxious uncertainty as Julie misses cue after cue, even as she holds the audience in rapture: “Julie could convert anyone in minutes, hush the room like a church.” But Julie’s holy command of performance fails to find a place to reroot once Yes and Kit move on to more conventional paths. Julie loses herself in addiction, and You Are the Universe fizzles out before it’s fully lit.

The story of most punk bands, unlike so much punk lit, does not end in stadium tours or even storied clubs like CBGB. In Patti Smith’s memoir Just Kids, she is in constant orbit of legendary artists frequenting legendary haunts. She puts on a play with Sam Shepard. Sandy Pearlman envisions her as a front woman. She consoles a rejected Janis Joplin in the Chelsea Hotel. But You Are the Universe, like so many others, does not exist at the epicenter of a countercultural awakening. There is no Max’s Kansas City in the arid sprawl of West Texas. We Were the Universe offers a less-mined truth: that many bands dissipate into the demands of domestic life, or spiral in the face of this reality.

We Were the Universe is an honest punk novel: albums are recorded in closets and drugs are done in trailers; there is artistry and there is experimentation and there is self-destruction, but the band only has each other to bear witness. A would-be star is left adrift to drink too much wine on her mother’s porch and teach wealthier children how to play the piano. Yes and Kit, two not-quite-stars, have intentional and unintentional children and sing to them. Gilda, this unintentional child, who clings to Kit’s “mouth sounds,” is forged by the body and screams with abandon. Looking back, You Are the Universe was a youthful explosion that burned while it had the oxygen, imprinted profoundly on few, and then was extinguished so creation and death could follow.

Under this haze of grief, We Were the Universe brings punk rock into conversation with the body and the self, which so often feel opposed to the order of domestic life. It can be easy to forget the physical stakes of music. Iggy Pop, godfather of punk, has often been identified as a man possessed, his onstage demeanor void of composure. There was something feral in his performances with the Stooges, where bloody scratches and uncontained howls were expected. We Were the Universe puts a premium on all that is carnal. Kit is constantly contending with the ways her body is leading (Kit likes a leader, likes to let herself “be pulled—it makes things so much easier”): she yearns for hot mommies and hot daddies and binges porn for monogamous release. Her body is a tool for negotiation, as she breastfeeds into Gilda’s toddler years (when is it too late to use your body to soothe a wound or end a tantrum?). She overheats in a natural spring while on an MNE (Meaningful Nature Experience), her instinct to escape and protect simultaneously activated.

Prior to We Were the Universe, notes of punk rock were brewing in Parsons’s debut story collection, Black Light (2019). In these stories, characters are adrift on buses across the glorious wasteland of America’s in-betweens, drinking too much and ignoring too much and giving into their primal instincts. The ideals of nonconformity and anti-establishment belief, of anarchy and authenticity, ask for status quos to be ruptured and turn the messiness of life into a badge of honor.

In We Were the Universe, the principles of punk rock that are historically categorized as counterculture begin to read as human nature, waiting desperately for an outlet. Julie’s turn to substances once the band dissolves speaks to this; addiction is not a symptom of a punk rock lifestyle, it is a symptom of humanity. It is nature and nurture and an insidious gamble upon our souls. Dependency is born from the cage one is raised in, or a gene inherited, coded in such a way that the high never lifts its host all the way out, but also never stops promising “next time.”

The attitudes of punk linger in Kit’s mind; an ongoing sense of questioning, of desire, of resistance are palpable as she grapples with death, lies to her therapist, reconsiders her associations with other mothers (including her own). Through Julie and Kit, Parsons explores whether punk is an excavation of one’s circumstances or a desperate attempt to pull oneself out and away. Playing in a band provided an alternative reality to dream about, but it was also something to pass the time, to put their voices somewhere until they could leave, or until they couldn’t. And if punk rock is an untethering, motherhood is a foil as the most tethered act of creation.

How does a former punk princess acclimate to the suburbs? This is the subterfuge Parsons deftly works into her writing. Perhaps all parents are double agents of a previously erotic and erratic life. Will a sliding-scale therapist and a trip to the mountains with all its healthy waters soothe the soul? Or is the chicken soup in fact screaming through the night terrors and furious masturbation? Is it Kit fully accepting this life as it endlessly expands away from the point in time when three alive girls formed a band and drank cactus psychedelics on the weekend? Is it being haunted, or is it letting go?

Do the women of Lloronas know they left me with something in my body that can transport me back across time and space, where I am screaming to lyrics I don’t know, gin dripping down my plastic cup and onto my wrist? I wonder what parts of their lives feel tedious and tragic and unknown. For a moment, our universes touched, and now we drift. ![]()

Madison Ford is a Texas-based writer and actor. Her work has appeared in Texas Monthly, the Brooklyn Rail, Architectural Digest, Glasstire, and elsewhere. Among her many fascinations are hauntings, art, and the body.