On the other end of the phone was a scared little punk. My ear glued to a beige Panasonic landline, wearing a T-shirt with some cartoon character, I was terrified that the pulse tone might end. The silence that followed each ring filled my parents’ bedroom with a tense comfort. Someone would soon pick up the call. It was 2001 and Attaque 77 was visiting Bolivia for the first time. The punk band from Argentina was touring my country, and a string of promotional activities took them to the booth of a radio station in Cochabamba. I was the fourteen-year-old son of a middle-class family with an ordinary cultural life. A midweek punk rock show was out of the question. Calling the radio station was the closest I could get to the band. That was enough to frighten me.

I had started listening to Attaque 77 a few months earlier. It was not an obscure band by punk standards. I’d heard of them in high school. I attended a school founded by Dutch Augustinian missionaries in Cochabamba. Their priorities were clear: anything unrelated to math or science was filler. It was not a culturally stimulating environment. I felt adrift until I met Carlos and Jorge, two would-be punks who had also chosen to sit in the last row of the classroom. We realized we liked similar bands. Green Day and Blink-182 were as huge in Cochabamba as on the rest of the planet. They worked as icebreakers. I started digging deeper online and discovered older acts like the Sex Pistols and the Exploited. I burned a CD-R with their music and brought copies to my friends. Then Carlos began telling me about Latin American punk bands. Argentina was home to a bustling underground scene we could only dream of in Bolivia. Attaque 77 was soon part of the conversation.

Since its origin, punk has been an escape route from monotony and voicelessness. It continued to play that role in Latin America as a new century dawned. In 2001, punk was as necessary as ever. Fear and silence haunted Argentina. Riots rendered music irrelevant as the country plunged into a crisis following a decade of pro-market reforms that gutted the working class. Rock Argentino had been a cultural behemoth in Latin America for decades. Its imprint on daily life in Argentina was indelible. Yet as discontent grew, leading Argentinian bands appeared distant from the experience of their fans.

Things had not grown quiet beneath the surface. Underground musicians narrated the degradation they observed in suburban neighborhoods. Using punk as an outlet, Attaque 77, Dos Minutos, Flema, and Fun People spearheaded a movement that didn’t need the mainstream to thrive. Their songs talked about unemployment and marginalization with a lived-in potency. Able to portray their surroundings, they connected with audiences beyond Argentina. The ripples would soon stretch beyond the country’s borders.

Bolivia had issues of its own in 2001. The turmoil did not reach my surroundings, however. Cochabamba is not Buenos Aires. It numbs you with its good weather and placid tempo. By the end of the nineties, it had ossified into a non-place. Not an economic, political, or cultural center, it was a languid city with a conservative mindset, an easy place to live if you had the right background. The internet became my portal. Going online, I discovered punk. Its ideals and sounds were a transformative force that would shape the rest of my life. The music coming out of the industrial outskirts of Buenos Aires spoke of unfettered freedom and individual affirmation. It pointed me toward a community that started in the halls I shared with my friends in high school and encased the world. A phone line would get me there. Waiting for the call to the radio station to be taken, I stared at a precipice. Anxiety retreated when the dreaded “Hola” came through. It was time to talk.

![]()

Argentina and the Promise of the Underground

Rock Argentino is part of such a well-established cultural heritage that it has an official date of birth: June 2, 1966. On that day, Los Beatniks released their debut single, “Rebelde.” Though there were earlier efforts to develop a localized version of rock, it is telling that musicians, fans, and historians have decided on that song as the originating salvo. Antiauthoritarian and headstrong, “Rebelde” codified the values of early rock in Argentina. “Conservative society could not believe we had ideas of our own,” recalled one of the band members when talking to Argentinian news station TN decades later. Nonetheless, clamped down on by dictatorial regimes, rock music would remain a niche phenomenon in Argentina until the early eighties.

Once democratic governments returned beginning in 1983, rock Argentino began to grow as a society-wide phenomenon. New styles and themes took shape as the yoke of censorship was lifted. Levity, fun, and danceability opened the door to large audiences, leaving behind the subterfuge and militancy of the dictatorship years. Bands like Soda Stereo and Enanitos Verdes were part of that wave. Their timely songcraft resonated with young audiences in other Latin American countries newly open to democracy. Soon, they would become stars and continue to tour the continent into the next decade, establishing rock Argentino as modern pop music for the masses.

The eighties and nineties marked the heyday of rock Argentino. But by the end of the nineties, the once vigorous movement seemed to wane. The trailblazing artists that spurred the movement had grown old, retired, or disappeared in a psychotropic cloud. Their country was also changing. The economic measures purported to foster private investment in Argentina proved to be a consumeristic mirage. Poverty and social exclusion became commonplace among fans who could no longer recognize themselves in the songs they used to love. Looking for music that reflected their lives, many working-class kids out of a job decided to form bands. With no musical training but plenty of things to say, these kids found a path in punk and its premise of raw expression above technical skills.

![]()

A Punk Invasion Brewing in the Outskirts

Punk arrived in Argentina in the late seventies. The country was then going through the so-called Proceso de Reorganización Nacional, a period marked by dictatorial regimes responsible for the disappearance, torture, and death of thousands between 1976 and 1983. The first punk bands in the country were fiercely political and saw their work confined to clandestine spaces. Los Violadores, Alerta Roja, Los Laxantes, Trixy y los Maniáticos, and Los Baraja were among those pioneering acts. In strict DIY fashion, their music was distributed on crude cassette copies. All information about the bands was available in a handful of fanzines only the initiated had access to. Scarcity was as much the result of oppression as material limitations. If mainstream rock was repressed and persecuted under the dictatorship, being a punk seemed like a suicide mission. Talking to a radio station many years later, the leader of Los Violadores remarked: “They tried to silence us all, but we opened our mouth; you had to resist.”

Once the political situation changed, around the second half of the 1980s, a circuit of underground venues emerged alongside new independent record labels. Parakultural and Radio Tripoli were the dual beams of the nascent movement that Argentinians called “el under,” a crucible of countercultural art fermenting outside the mainstream. Parakultural was a performance space where punk acts and avant-garde theater cross-pollinated. Radio Tripoli, a record label, took it upon itself to propel punk and metal in Argentina. A liberated nightlife allowed for rougher edges and gloom. Benefiting from that ecosystem, a new crop of bands that would define punk rock in Argentina in the 1990s started to sprout.

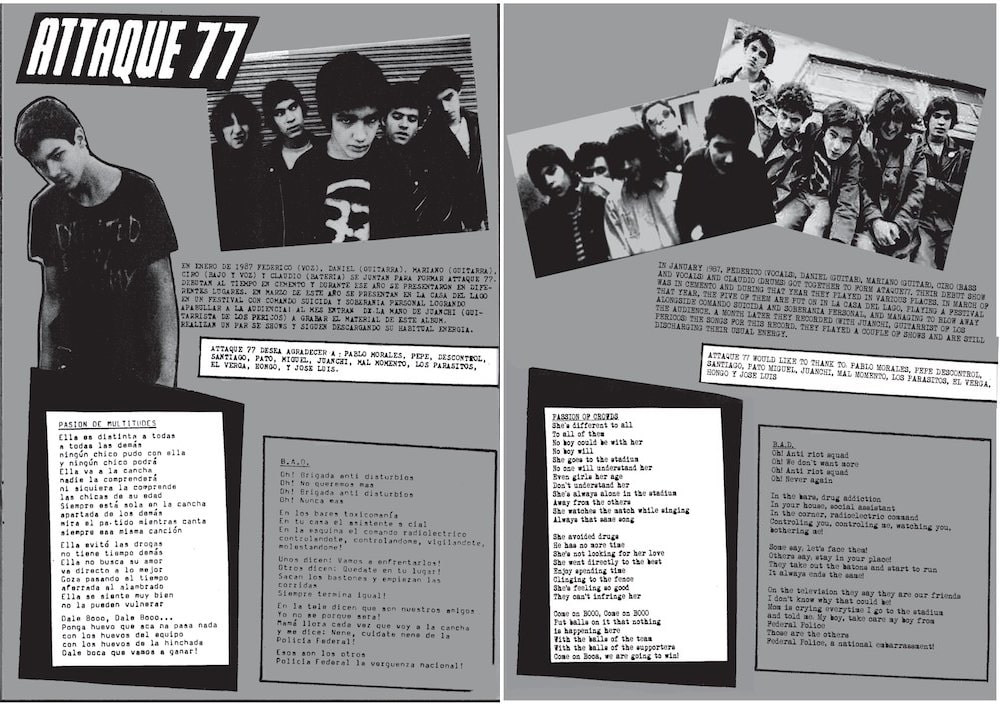

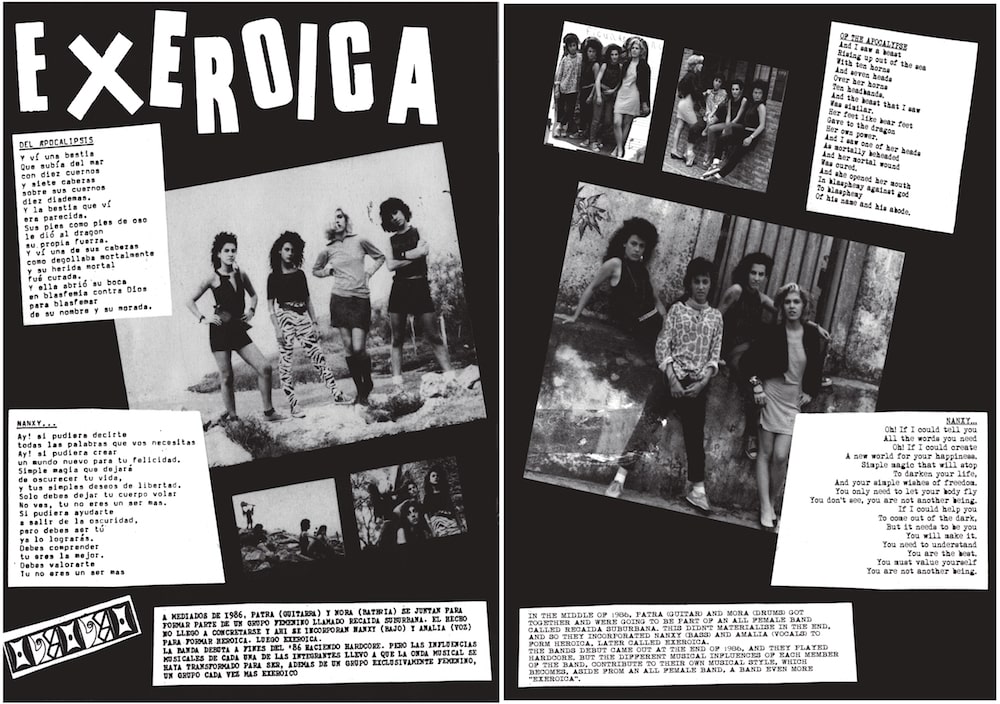

The upswell that would break with the new decade was captured in the compilation Invasión 88, a real-time portrait of the Argentinian punk scene as it morphed. Released by Radio Tripoli in December 1988, the album links the abrasive first wave of Argentinian punk with a new cluster of acts. Los Laxantes and Los Baraja bookend the album, each with two tracks anchored in a late-seventies style that could still agitate and bite. These foundational bands are joined by Attaque 77, Flema, Exeroica, Rigidez Kadaverika, División Autista, Conmoción Cerebral, and Comando Suicida. All were recently formed acts, connected by their age, suburban background, and a loosely individual approach to political issues fit for the postdictatorial mood. They were punk’s new guard.

More than a sampler of music to come, Invasión 88 presented a generational shift and a geographic transition in the scene. Downtown spaces like Parakultural would close in the nineties. At the same time, some of the bands that incubated there began to penetrate the mainstream. The art students and bohemians who populated the early punk trenches proceeded to find new homes. Nineties punk in Argentina needed a new gravitational center. The anthology gave some clues about where to find it.

Several of the Invasión 88 bands had played Parakultural but were not Parakultural acts. They lacked the dark and conceptual elements that colligated the work of Todos Tus Muertos or Los Pillos, flagship Parakultural bands. The Invasión 88 lot was part of a younger and more convivial milieu. They would not be homeless for long. All it took was a return to their origins. The kids who formed bands in high school moved to venues closer to the neighborhoods where they lived. In that process, a conduit for rebelliousness implanted itself in the working-class outskirts of Buenos Aires, hailing sounds and themes relevant to the context.

![]()

Punk barrial: Young Love, Bar Fights, and Soccer

Attaque 77 was the highest profile act to emerge from the Invasión 88 scene. The band was founded in 1987 by Mariano Martínez, Ciro Pertusi, Federico Pertusi, Daniel Caffieri, and Claudio Leiva. They were a group of friends who bonded over a shared love of the Ramones and the music that came out of the 1977 punk explosion: the Clash, the Damned, and the Stranglers. Only a year active as a band by the time they were included in Invasión 88, Attaque found its place in the scene thanks to a fresh-faced take on classic punk.

With mischievous charm, Attaque deployed frenzied melodic songs about high school shenanigans and young love. Any teenager could relate to the music because almost everyone in Attaque was still in their teens. “We were out-of-tune brats,” admitted the band in an interview with music journalist Francisco Prim celebrating fifteen years of activity. Growing pains aside, Attaque had figured out its identity from the get-go. The two songs it recorded for Invasión 88 showcase its character and landmark themes: soccer fandom, loneliness and individual assertion (“Sola en la cancha”), and a suburban rebellion where the enemy is an undefined system and family acts as an anchoring force (“B.A.D.”).

While the focus on situations typical of a teenage everydayness contrasted with the stereotypes affixed to the underground movement, Attaque remained a recognizably punk band. Facile provocation was not beneath it, nor did the band excise sloganeering from its songcraft. Instead, they built on that foundation. Attaque’s full-length debut, Dulce Navidad (1988), attested to its songwriting development, featuring what would become the defining shift in Argentinian punk during the nineties: Attaque employed the punk idiom to explore the inner life of working-class youth, telling stories of broken homes (“Papá llegó borracho”) and the soul-crushing nature of work (“Gil”).

Becoming a fully formed band so fast has its downsides. No punk story is complete without a sellout. That fate befell Attaque despite its groundbreaking role in punk barrial, the branch of Argentinian punk that gestated in the outskirts of Buenos Aires. The path of the band forked early and perhaps unavoidably. Attaque had a hit with “Hacelo por mí,” a song from their sophomore album, El Cielo Puede Esperar (1990). A punk ballad with a steady beat and a catchy chorus, “Hacelo por mí” narrated a story of heartbreak that was not so much about a search for catharsis as it was about acceptance of grief. The song gained momentum slowly and unsurprisingly. Within months, Attaque went from playing bars to selling out Obras Sanitarias. This Buenos Aires arena has been a barometer of popular acclaim in Argentina for decades. Playing there, a venue with a capacity of five thousand people, meant that a rock band had “made it.” Not least when on an indie label like Radio Tripoli.

Though Attaque would spend the nineties refusing to play “Hacelo por mí”—like any self-respecting punk act—the band was snatched up by BMG shortly after the song stormed the charts. Attaque had reached a turning point. It now was a major-label act. While changes in its music were slow and gradual, by the end of the decade, Attaque was putting out power pop songs that paid homage to the Beatles. The band’s choices put it on a trajectory of international stardom that peaked in the early 2000s with several Latin American tours and increasingly ambitious albums. It may have planted the seed of punk barrial, but Attaque was not destined to be a cult act. Instead, much like its beloved Ramones, Attaque would serve as a gateway to punk for many teenagers.

![]()

We Come from an Industrial Neighborhood

Heavy metal growled like an infernal cauldron because it originated in the industrial heart of England. Motown’s assembly-line approach to music making was inspired by the automobile factories headquartered in Detroit. Transcendent music canalizes the defining qualities of a time and a place. Dos Minutos, a punk band from Valentín Alsina, wanted to make songs for esquinas, corner hangouts that spontaneously crop up around a shop, a fast-food stand, or a TV set playing some soccer match. In their neighborhood, esquinas were the anonymous spots where friends would meet to have a beer, complain about work or their lack of it, and spend an otherwise-wasted afternoon together. Dos Minutos would own that vibe.

The corners of Valentín Alsina had many stories to tell. Located in the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires, just outside of the capital, Valentín Alsina was home to many workers from nearby factories. In the nineties, Argentina’s industrial force began to decline following government policies to foment free trade and foreign investment. Soon, esquinas were no longer just an option to socialize. They became the only refuge for locals facing bleak prospects. Wanting to write songs informed by the musings of young men with no hope, Dos Minutos was the right band at the right time.

An essential part of Dos Minutos’s lore claims that its live debut occurred the same day Carlos Menem was sworn in as the president of Argentina. In July 1989, the country suffered record-breaking inflation levels amid protests and looting. Menem was elected to control hyperinflation and modernize Argentina’s crumbling economy. His neoliberal policies appeared successful at first, though they kick-started a cycle of unemployment and deficit that still haunts Argentina. That was not the narrative mainstream artists were injecting into their work.

Dos Minutos realized that rock Argentino had overlooked the experiences of youth in the margins of Buenos Aires. Influenced by the second wave of British punk (Sham 69, U.K. Subs), Dos Minutos viewed punk as a means to an end. The goal was to tell stories of having a lousy coffee on your way to a dead-end job, gang skirmishes down the street, and friends who became police officers betraying their old comrades. In the words of music critic Walter Lezcano, “Dos Minutos gave artistic value and sonic grounding to songs that put your place of origin at the center of creation.”

If Attaque 77 happened to be a band with members who lived in barrio Flores, Dos Minutos tied its identity to its birthplace, Valentín Alsina. Their debut album, Valentín Alsina (1994), displayed on its cover the arches that welcomed visitors to the neighborhood and included a song celebrating the band’s home. The half-boozy anthem and half-Oi! love letter “Valentín Alsina” boasted about being from a place where tired workers and drunken regulars define who you are. It embraced the band’s native ground as a collection of shared experiences and odd people the locals found dear. This music could not have come from anywhere else.

Though Dos Minutos was signed to Polydor, a major label, carrying so much of the neighborhood within helped them sound like the band never changed. Whereas Attaque has followed a career arc akin to that of the Offspring, Dos Minutos most resembles punk rock lifers NOFX. Yet there was no opposition between the two bands. On the contrary, Dos Minutos took the thematic innovations of Attaque one step further. Dos Minutos’s music aired out an encroaching hopelessness without cynicism. The songs were sustained by irrepressible fun and old bits of wisdom. They insisted that when everything else fails, only friendship can save you. With sincere belief, Dos Minutos proclaimed that there was a rebellious streak in camaraderie that was as powerful as any Molotov cocktail.

That radical originality has allowed Dos Minutos to endure strepitous lows. There’s nothing new about getting drunk with friends because jobs are scarce. Dos Minutos’s claim on posterity isn’t based on the members being slackers. They were proud children of an industrial neighborhood eviscerated by economic reforms. Dos Minutos succeeded in mixing goofy street punk with the mass enchantment of a soccer stadium. The music had an urgency fitting suffocating times without losing the empathy and strength of a community.

Dos Minutos transcended by enacting the totality of the punk ethos: be true to who you are and put that into music irrespective of the resources at hand. That is why they inspired people as different as cumbia artist Pablo Lescano and Spanish indie rock outfit Carolina Durante, becoming more than bumbling punk boozers or a rabid working-class band that decided to tune up at the exact moment their country went to hell.

![]()

Otras canciones: Changing Times in the Underground Scene

By 1998, the political stability and economic growth that Argentina enjoyed in the early part of the decade was over. A few months would pass before the upper echelons of society felt the recession, but social unrest had begun to build up. Things had also changed in the underground scene. Ten years after the release of Invasión 88, Attaque 77 had a platinum album in Otras Canciones, a grab bag of punkified Latin American pop songs. In truth, it was a profitable release that kept pushing the band away from its roots. Dos Minutos was treading water after two albums that repeated the Valentín Alsina formula with diminishing returns. Unlike the still ascendant Attaque, fresh off a continental tour, Dos Minutos struggled to book shows in Argentina. The economic crisis had dried up their audience.

Of the ten bands featured in Invasión 88, only Attaque and Flema remained active in 1998. The first survived as a punk-adjacent alternative rock band. The latter had reformed with an entirely different lineup. But the underground circuit did not disappear when those bands dissolved or veered toward the mainstream. Many smaller acts that had started their run in the nineties sustained the movement. It was intriguing to imagine a punk anthology that captured the early blaze of a movement just like Invasión 88 had done. There was an Invasión 99, though this time it was curated and released by Universal Music. Both founders of Radio Tripoli were working for that label and had established an indie-to-major pipeline. But their age and occupation had removed them from the involvement necessary to keep their finger on the scene’s pulse.

Invasión 99 could never live up to its predecessor. The stature and legend of the original album were impossible to match. Devoid of cultural cred and underground representation, Invasión 99 was a shameless cash-in that included six tracks by Flema or its offshoots, a Rolling Stones cover, Dos Minutos playing songs by other bands, and a mishmash of dumbly entertaining tunes and political agitation. It also overlooked women, who had been integral to the scene from the start. Exeroica, part of Invasión 88, was an all-female act. Patricia Pietrafesa had been running the fanzine Resistencia since the eighties and led the queercore act She-Devils. Multimedia project Homoxidal 500 brought to the table transgender rights and sexual liberation. The chummy energy of punk barrial overshadowed female and gender nonconforming participation in the scene, but their presence had not ceased to be fundamental.

The makers of Invasión 99 had artists to choose from who were above the higher rungs of the scene that the 1988 anthology had helped launch. Any attempt to depict the underground movement emerging in late-nineties Argentina should have featured Embajada Boliviana, Loquero, and Eterna Inocencia. These bands exemplified the trends developing in Argentinian punk at the end of the nineties: a turn to the cities outside Buenos Aires, the consolidation of hardcore as a scene of its own, and a pervasive disillusionment. Loquero came from Mar del Plata, a coastal town on the eastern tip of the province of Buenos Aires, while Embajada Boliviana was formed in La Plata, a city located north of Buenos Aires. Eterna Inocencia and Loquero shared a proximity to hardcore—in the case of Eterna Inocencia approaching the vulnerability of emo, whereas Loquero pursued debasement. And the bands would no longer talk about dysfunctional families or working-class neighborhoods, instead channeling the negative emotions of the time via darker subjects like depression and murder.

The music industry was ready to prey on these acts. Embajada Boliviana started playing in 1990, picking up where Attaque 77 left off. The band’s calling cards were fast yet hummable songs of teenage love, pain, and rebellion. Embajada Boliviana’s first three albums, unwavering lo-fi affairs, garnered it a cult following. The hope was the four-piece would swing left where Attaque 77 went right. That didn’t quite happen. Embajada Boliviana stayed on an independent label, but its songs had been so polished by its official debut in 2000 that the original charm was gone. The band could never recover from the feeling of a squandered promise. Loquero was more resistant to containment, making darkness and paranoia the driving forces of its music. “My only muse is my disenchantment,” proclaimed Loquero’s primary songwriter and singer, Chary, in an interview with the local press. The band’s themes of necrophilia and self-harm were nothing like those of the preceding wave of punk bands. Intense and brooding, Loquero retained a strong minority following amid tumultuous times.

Eterna Inocencia was the youngest band among the newcomers, starting its activities in 1995. Having missed the brief Argentinian economic bonanza, its aspirations were firmly planted underground. Eterna Inocencia self-released its music, called the hardcore circuit home, and remained disinterested in courting the masses or joining the industry. The band’s “poetry of emancipation,” according to music critic Fernando Núñez, took punk as far as it could go in a “third-world capitalist country” plagued by crisis.

Eterna Inocencia would even be part of an Invasión compilation. Acknowledging the sham of Invasión 99, a hardcore cooperative put together Invasión 2002. The project’s promoters knew that the album’s effect could never be the same as that of Invasión 88. “That was the fanzine generation; this is the chatroom generation,” Eterna Inocencia’s singer would say when discussing the anthology with Buenos Aires newspaper Página 12. Times were different. Argentina was still undergoing a recession, and the music industry had collapsed due to file sharing. The internet was the force Invasión 2002 wanted to leverage. The music could be found online for free. Still, the eight bands included on the album would go on a national tour of Argentina, organizing skate shows and engaging the audience where they were. No matter how much the media transformed, or if the bands who laid the groundwork for the scene faltered, Invasión 2002 set out to prove there would always be someone keeping the movement alive.

![]()

Counterculture, Self-Sabotage, and a Sense of Belonging

If one pulls the thread connecting the three issues of the Invasión anthology, one can find other bands meaningfully involved in the counterculture regardless of their non-inclusion in the compilations. At the intersection of punk, hardcore, and alternative rock, Massacre, a new incarnation of Flema, and Fun People embodied three trails that crisscrossed Argentinian punk rock in the nineties.

Massacre was left out of Invasión 88 despite being the first band in Radio Tripoli’s catalog. It had formed in 1986 and recorded an EP for Radio Tripoli under the name Massacre Palestina. For years, they were stalwarts of the embryonic hardcore scene. Walas, the band’s frontman, was invested in skate culture and held wide-ranging artistic ambitions. Free from punk orthodoxy, they would craft an idiosyncratic sound that brought psychedelia into a hardcore foundation. Shortening its name to Massacre, the band issued its full-length debut in 1992. Through the decade, Massacre enjoyed steady growth as one of the pillars of the Buenos Aires underground, ultimately breaking into the mainstream in the late 2000s.

The story of Flema is the story of Ricky Espinosa. A larger-than-life character who came to represent the degradation of Argentinian society, Espinosa lived to the extreme and found an absurd death. He was only thirty-four when he either jumped from a balcony after losing in a video game or fell while intoxicated. His reckless provocation and self-destructive impulses make both scenarios likely. However, Ricky Espinosa was no GG Allin. He was a sensitive chronicler of his social environment, capable of revolting metaphors, hilarious one-liners, and street-lingo lyrics that could have been a Baudelairean poem.

Flema had been part of Invasión 88; Ricky Espinosa was then just the band’s guitar player. When all the other members left in 1989, he took over as singer, songwriter, and ideologist. He reshaped Flema in his image, resetting their style and themes from a run-of-the-mill death rock act into a no-brakes rock ’n’ roll unit. His songs would recall Dos Minutos in their melodic wit and simplicity, still talking about day-to-day life on the outskirts of the capital. But those environments had transformed in the late nineties, and Flema portrayed that. Post-adolescent listlessness gave way to adult despair as misery became a tangible reality. When singing about the neighborhood drunkard, Ricky Espinosa does not memorialize a beloved character everyone knows; he tells us that he died from drinking, and no one went to his funeral.

Separating the myth from the work in the case of Ricky Espinosa is fruitless. He played up the anarchic side of his character to get media attention and further his music. Banned from playing at any venue in Buenos Aires, he would be a frequent guest on TV and radio shows, where the hosts let him run with his baiting. There were sordid and vulnerable qualities to that behavior. An infamous story tells how once Espinosa bought out his dealer’s supply, took it all in, and started vomiting on the street . . . just to eat back the vomit to taste again what he had for lunch.

Ricky Espinosa would not have shied away from that episode in retelling his life. However, the tale would not be complete without mentioning that he was a genial person who radiated charisma on and off stage. Ricky Espinosa wrote a song about being “fucking happy” sniffing glue. Whenever someone confronted him, saying kids started doing that because of Flema, he would deflect by calling them ignorant. No one could speak for Ricky Espinosa. In an interview with journalist Lala Toutonian, he described himself with utmost clarity. Asked why he hurt himself so much, he replied, “You cannot see the pain of the heart, and I need to exteriorize everything; if I bleed on the inside, it must show on the outside.”

Carlos Rodríguez, best known as Nekro, was one of Ricky Espinosa’s greatest friends. The leader of Fun People, and a straight-edge vegetarian who wore his heart on his sleeve, Nekro understood Espinosa like few others. Lifestyle differences aside, both were sensitive artists willing to give their lives for a cause. They made music together and followed paths true to their beliefs, irrevocably punk and coherent despite superficial divergences. Thirty-five years after he started, Nekro remains the unwilling king of the underground in Argentina.

Fun People tirelessly helped build the hardcore scene in Buenos Aires through the nineties, pushing it forward as a safe space for ideas and people. Back then, hardcore was a tremendously male-coded realm, with aggression and violence becoming common currency. Fun People set itself apart by calling its music “antifascist gay hardcore.” The band certainly lived up to the label. Nekro would short-circuit the prevailing machismo and hostility of hardcore shows by pulling out an acoustic guitar and covering a fifties ballad in the middle of a rampaging concert, childlike cartoons of animals decorated the band’s covers, and many of its songs adopted the voice of queer protagonists.

Political ideas began to evolve in the scene thanks to Fun People. The band avoided spent ideologies and mindless destruction. Nekro’s compositions subverted the conventions of the hardcore scene. His fiercest songs tried to comfort women wondering whether to end undesired pregnancies, and the most tender ones empathized with teenagers in the grips of eating disorders. Yet, instead of ejecting macho types, he would welcome them into shows where information on legal abortion and gay rights was everywhere. In the face of a cruel society, Nekro believed that doing a small part made a great difference. Decades into his career, he would insist that there were battles still to be fought and a new world ready to be made.

Fun People was not proselytizing. It cared for its audience and wanted to make music true to that ideal. The fans at the shows were often in their early teens. The band noticed and worked to make those gigs “violence- and prejudice-free spaces.” Chuly, the guitar player, remarked to Salto magazine that the political slogans they sang were meant to ensure the safety of the fans. The genuine communion that took place at their shows, a combination of “counterculture, risk, self-sabotage, hardcore-metal-pop, adrenaline, and a sense of belonging” in Chuly’s words, forged the minds and personalities of many of their fans for the rest of their lives.

In a time when the underground had splintered and curdled, asphyxiated by the economic crisis and the temptation of nihilism, Fun People mattered. Flanked to the left by the punks too drunk to cause the system any trouble and to the right by those too privileged to risk fighting, Fun People devised a new form of militancy. These compassionate anarcho-pacifists with forward-thinking ideas did not try to convince anyone. You had to opt in. All Fun People knew was that punk could provide a moral education and that no weapon is as powerful as freedom.

![]()

A Flare to Signal Ominous Times

In 2021, composer and University of Buenos Aires professor Martín Liut edited a book on the music that “anticipated, documented, and processed” the economic crisis. With two decades of hindsight, his team chose twelve songs to retell that moment. Punk was not there. The closest was “Argentina 2002,” a track recorded by former Parakultural fiend Palo Pandolfo. It was not a rock song. Pandolfo, one of the figureheads of the underground through the eighties and nineties, had apostatized, intuiting that cuarteto, a form of tropical music popular in the poorest neighborhoods of Buenos Aires, had more to say about society.

In truth, punk sealed its fate years earlier by heeding the music industry’s call. The economic crisis would have been enough to kneecap any cultural activity in Argentina, but the blow became mortal when the global music industry collapsed. Domestic internet connections and file-sharing platforms cut the industry’s profits in half in the early 2000s, inaugurating what has been called “a lost decade.” Argentinian punk bands, shackled by their own inertia, were scrambling to save themselves as the industry went down, alien to their fans’ problems.

Attaque 77 was still one of the most visible bands in the countercultural field in the early 2000s. It was expected to say something. That responsibility cast a long shadow when preparing Antihumano (2003). Attaque 77 began to break under the weight of an album framed as a grand artistic statement. In the mold of Sandinista! (1980), a work of hubris and excess that itself marked the downfall of the Clash, Antihumano would wrestle with the band’s past and future. On the surface, the pop leanings that had reconfigured Attaque were gone, replaced by darker hues in tune with the alternative rock dominating the airwaves. Yet the album gave Attaque its last big hit in “Arrancacorazones,” a lovelorn ballad featuring a string section. Nothing else clicked. Antihumano is filled with multi-section tracks lacking the ingenuity of the band’s early work and the catchiness of the songs that introduced it to the masses. The album betrayed a confused and overstretched band. Unmoored. Out of time.

Smaller acts outside the industry faced increasingly worse odds. Fans had no money to buy music or attend shows. Performing spaces shut down. Many musicians stopped playing. The final nail in the coffin came in December 2004. Recovery had barely started when a downtown venue burned down, causing the death of 194 fans and injuring 1,432 others. Callejeros, a rock band with working-class roots, was playing when a lost flare caught the flammable roof. Security exits were blocked, and the venue was not properly fireproofed. Thousands of fans were trapped. The Cromañón Tragedy, named after the venue, brought the underground to a halt, forcing it to face a harrowing reality.

Although the band playing that night was not punk, the owner of República Cromañón was the same person who ran underground venues where nearly every punk band performed in the eighties and nineties. But it was not simply a matter of personal responsibility. The calamity had been caused by negligence, corruption, and a tainted concertgoing culture. Many venues failed to comply with security standards and had been operating for years just bribing the authorities. On their side, musicians and audiences adopted a regressive, soccer-fan mentality. It all snowballed from the bands’ authentic fandom. Attaque 77 loved Boca Juniors and wrote songs about going to their games. Punk songs began to be chanted in soccer stadiums. Those practices continued to scale and intermingle with criminal elements involved in soccer hooliganism. In the early 2000s, rock followers competed in their fervor, using flares, fireworks, large banners, and other elements that added to the ritual aspect of the show, to the detriment of engaging with the music as a community. Justified or not, thorough scrutiny of countercultural spaces played to the tune of conservative political forces in Buenos Aires. Closures were unavoidable. The underground circuit that had been in place since the mid-eighties was coming to an end.

![]()

The Underground Knows Better

The internet, one of the factors eroding the music industry, would be the shot in the arm the underground needed. Once the initial shock passed, artists and fans began to see that global connectivity was an extraordinary tool to build a scene. Recording music had become more accessible thanks to home computers. Sharing those songs online with fewer material restrictions than ever before was possible. Copies were easy to make and distribute. There was no need to travel to other cities to reach fans. Moreover, audiences from distant places could join the scene through the internet. A new era for DIY culture was dawning.

With venues unavailable in Buenos Aires, underground bands formed elsewhere. Many started in the provinces and cities outside the capital. The media infrastructure had deteriorated as well. Newspapers and magazines disappeared as a result of the economic and music industry crises, giving way to webzines, blogs, chatrooms, and online forums. Underground bands had to relearn how to run grassroots operations. The precarious conditions and grim mood were reflected in the music, as it became more extreme and less melodic than before. In doing so, hardcore and punk opted to become a large, albeit confined, scene, similar to heavy metal.

Santiago Motorizado, a die-hard fan of Embajada Boliviana who studied visual arts in La Plata, was destined to be a key player in consolidating a new underground scene. He had been part of short-lived bands since the early 2000s, actively involved in the underground scene that coalesced around the National University of La Plata. He was not satisfied with what was going on at the time. An outmoded air haunted the circuit. The music was aesthetically and thematically stuck in the past, not to mention the lingering spiritual deflation brought upon by the economic recession. Illustrating flyers for emerging bands, Santiago Motorizado met fellow students interested in shaking off the nineties hangover. They decided to start a project together, naming the band El Mató a un Policía Motorizado.

At first the newly formed group circulated their music on CD-Rs like any independent act of yore. Then they realized other artists their age were trying to start something similar. Joining forces was the only option. Consolidating efforts in Laptra Discos, a new label, these bands attempted to live up to their heroes. They organized shows in their families’ garages, handed out flyers, sold homemade CDs . . . It was the same routine of old, tried and tested through decades of DIY activity. And then came the internet to transform things forever. With bands unable to play in Buenos Aires, Laptra created a website. Hiring payment processors or setting up security protocols was unnecessary; the music was there to download for free. It was Radio Tripoli reawakened with a website and MP3 files. A new underground modus operandi was born.

The first official release under the Laptra banner was El Mató’s debut, Tormenta Roja (2003). A modest EP with three lo-fi tracks, it incubated a manifesto. The new underground bands were fans of Attaque 77, Fun People, and Embajada Boliviana. Although they had wanted to follow punk acts from their teenage years, they were also inspired by Pavement, Los Planetas, and the Jesus and Mary Chain, the music they found through the internet. Those were novel influences in Argentina’s underground spaces, shifting the scene’s staple sound from punk and hardcore to indie rock and noise pop. Themes also morphed to adjust to the inward impulses of the art students who formed these bands. Still narrating stories from their neighborhoods and day-to-day experiences, they approached their personal problems and the new political reality from inside their homes, using science fiction metaphors and referencing TV shows from their childhoods. El Mató offered the earliest distillation of those new facets.

It was a transformation older bands had prefigured, even if they failed to grasp it. When promoting Antihumano, Attaque 77 commented to Barahúnda magazine that it was leaving behind adolescent anger for songs that tackled “melancholy and loneliness.” The environmental worries and sexual rights struggles of bands like Fun People and Eterna Inocencia were also part of the new zeitgeist. “We had the training to do it offline,” remarked the lead singer of Eterna Inocencia in an interview with Página 12 in 2022.

In the 2010s, the Laptra bands would find international success and mass exposure, touring in Latin America, the US, and Europe. El Mató would sell out arenas in their home country and headline festivals in the Spanish-speaking world. Unlike their punk forebears, they did not need to leave the underground for that. Thanks to the internet, someone from Colombia, Spain, or Bolivia could download the music, become a fan, connect with the band, and even start their own thing. The small-scale stories these bands told—meditative and vaguely romantic, finding refuge in friendship and love, remaining optimistic despite the psychic malaise of the world—resonated with teenagers around the globe just like punk had done before. A sense of continuity could be established by being true to who they were and putting that into music irrespective of the resources at hand. Nineties punk had left a fertile seed.

![]()

Growing Up a Punk in Y2K Cochabamba

Bolivian punk historian Fernando Hurtado claims that the show Attaque 77 played in La Paz in 2001 was a pivotal event for the local punk scene. What brought Attaque to Bolivia was the one-two punch of Otras Canciones (1998) and Radio Insomnio (2000), its most successful albums to date. Offering a radio-friendly refinement of Attaque’s signature sound, both albums shipped many copies and cemented the band past its punk roots. A priori, that version of Attaque was not the underground unit that one could imagine galvanizing a scene. Aware of that, the band honed its show to reach an emotional paroxysm. Old and new songs came from the same place, and on stage was the best opportunity to prove it. Being on mainstream radio was not a problem as long as the band’s vision of punk remained coherent. Just back from a Bolivian tour, Attaque’s lead singer shared with the Argentinian press his philosophy: “If you feel the need to make a difference, not only to call attention but because something moves you to live and feel differently, then that’s a punk attitude. Be yourself, do it yourself; do what you want respecting your neighbors.”

Attaque 77 visited Cochabamba on that tour. As exciting as that sounded to many young fans, it was not the first punk band from Argentina to come to the city. In 1997, Fun People played a show in Cochabamba. The small underground scene put together a show in a workers’ union hall and announced it using old-school flyers. It was the demonstration that Nekro, Fun People’s leading man, was right: punk didn’t need the mainstream to reach its intended audience and make a difference. Attaque picked a lane and achieved its goal; so did Fun People. However, the old DIY methods had their limitations. Ever resourceful, punk was finding other ways to conquer Bolivia.

It was also in 1997 that the local phone company began offering internet connections in Cochabamba. My parents were among the early adopters. Like any other teen with a computer, I found trouble. “Anarchy in the U.K.” was the first song I ever downloaded. Unwittingly, by signing me up for “internet classes,” my parents showed me how to set up an FTP server and access chatrooms. Before long, I was mainlining punk culture.

By the time Attaque 77 came to Bolivia in 2001, I had reassembled Invasión 88. Taking turns to use my family’s dial-up connection, I downloaded each track from LimeWire and then put together what had long been a near-mythical artifact. Using the home phone during the night, waiting hours to get songs that ended up being corrupted files, I plundered the virtual libraries of fellow punks. They would sometimes chat with me while we shared files. It was a formative ritual unlike the experiences of underground denizens who were just five years my senior. Although I didn’t see Attaque 77 or Fun People live in Cochabamba, I was slowly compiling their work. I had found a way to participate in the scene despite the distance and my family control.

My online activities took a while to manifest offline. The bookish son of a middle-class family, I hardly ever misbehaved. Yet there I was, listening to Dos Minutos sing about considering theft to feed your family, following the noxious exploits of Ricky Espinosa via Angelfire sites, well in the process of becoming a punk. No music had spoken to me that way before. Growing up, I would often say that I did not like music. Then came punk. And while many teenagers in Bolivia, the poorest country in South America, could connect with the themes of unemployment, loneliness, and despair that these songs tackled, something different drew me to them. I had begun to shed a heavy burden.

A conservative town has a way of shaping you while letting you think every choice is yours. It sells you each new step as a small triumph, though it ultimately leads to conformity. When I picked up the phone to talk with Attaque 77, I was terrified, as any kid would be when in the presence of unknown adults he admires. But there was more. I could see myself at the cusp of a great discovery.

Attaque 77 said they were on a mission to “open up kids’ heads.” That’s what punk did for me. Those songs imprinted themselves on a Bolivian teen because of their rebellious allure. They gave me a respite from being a good son. They illuminated the path I had been set upon by social circumstances. The information on animal rights I found in online fanzines was as crucial as the idea that it was okay to slack off and spend hours shooting the breeze with friends. Of course, I wanted to taste the danger Flema evoked in their songs. I prowled the depths of the internet to find the writers and philosophers Ricky Espinosa mentioned, sometimes in mockery, sometimes as sources of his imperative to break his body. It was all or nothing, but I was not alone. The friends I met through punk as a high school student would be there when we got chased by the police, went skateboarding and painted graffiti, or hid in alleys to drink and smoke. Punk taught us that it’s not feasible to live “one against the world.” By jolting me through a phone line, punk proved to me that there’s nothing more important in life than being true to who you are and putting that into your work, no matter what you do. It was a piece of wisdom spat out in two-minute songs about fucking shit up. The type of thing that gives you the vertigo of an uncharted phone call. ![]()

Javier A. Rodríguez-Camacho is a Bolivian writer based in Colombia. In 2009 he was named “Next Great Rock Critic” by Crawdaddy! magazine. His byline has appeared in Tiny Mix Tapes, Pitchfork, Spin, and Rockdelux. He is the author of Testigos del fin del mundo (Rey Naranjo, 2023), a retrospective of Latin independent music in the 2010s.