Cenizo, purple sage, agave, nopal, horse-crippler cactus. As Cliff surveys the Texas scrub flats, he recites a litany of local flora that surrounds him. But his friend Mikey is less than interested, preoccupied with his search for the old bullets that he turns into art. Cliff scolds him for his ignorance: “You live in a place, you should know something about it.” Their day takes an unexpected turn when Mikey’s metal detector discovers something in the desert sand: a sun-bleached skull with a ring beside it. The men hope for Spanish treasure, but they know Francisco Vásquez de Coronado probably wasn’t a Mason. They’ve found the long-missing remains of Sheriff Charlie Wade.

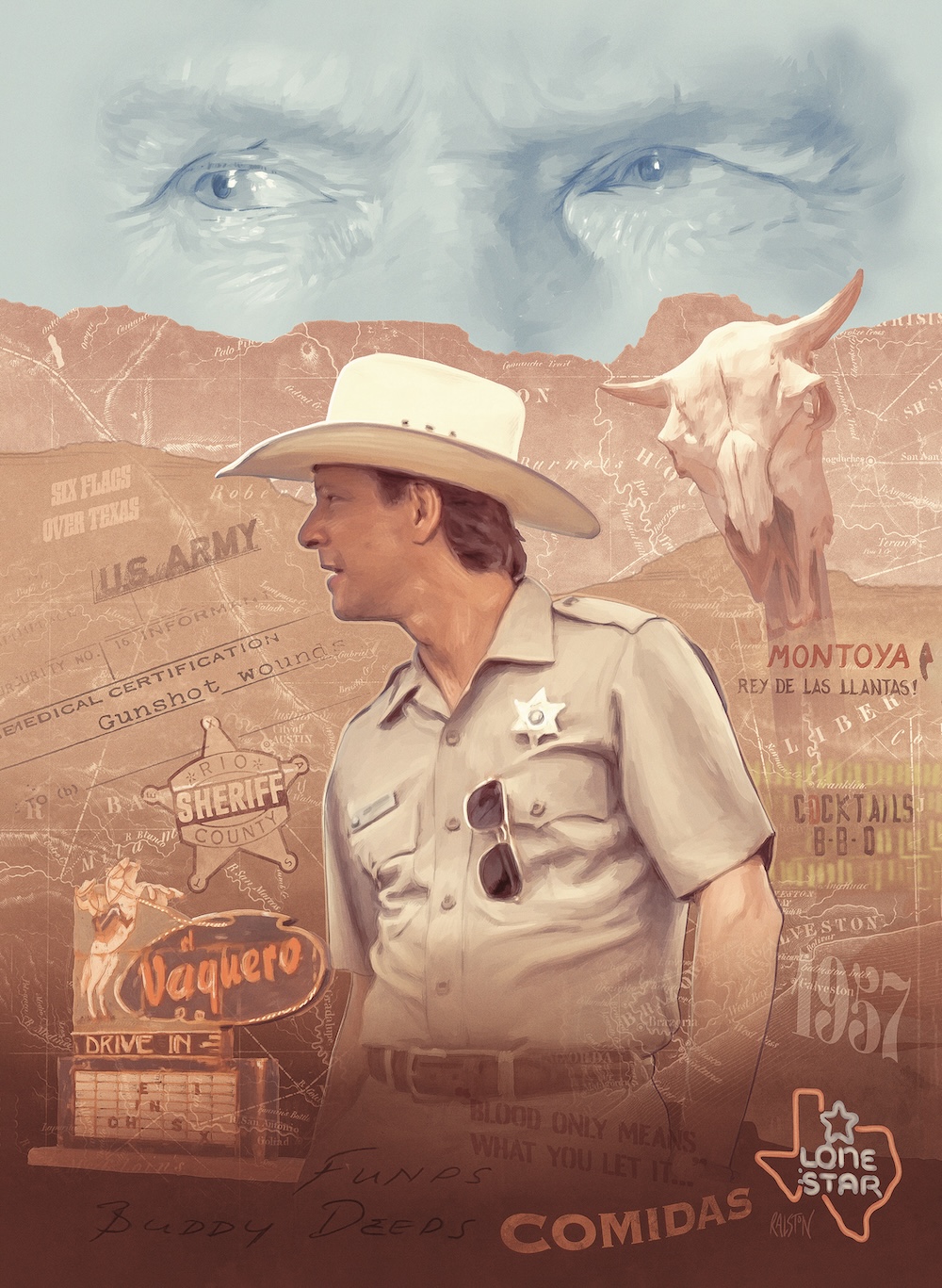

This accidental exhumation of a forty-year-old mystery kicks off Lone Star, a film Roger Ebert once rightly called “a wonder.” The filmmaker John Sayles’s noir-tinged neo-Western takes place in Frontera, a fictional composite of the Southwest’s border towns. Sayles creates a microcosm of humankind that feels as universal as it is uniquely Southwestern, a place that relays the area’s history through the families who live there: the Cruzes, the Paynes, and Chris Cooper’s quietly powerful Sam Deeds and his late father Buddy Deeds (Matthew McConaughey). Sam never really wanted to follow in his father’s footsteps to become sheriff, but he’s returned anyway, Frontera’s prodigal son. Even his campaign slogan leaned into his legacy: “One good Deeds deserves another.”

Everyone assumed Buddy chased Kris Kristofferson’s Charlie Wade out of town, and that he took $10,000 in stolen county funds with him. The film has compassion for each of its characters, but Wade is the exception—a murderous son of a bitch, his racism so vicious it’s tangible, with a soul as corroded as his buried badge. He’s the living embodiment of borders, their ultimate enforcer. And now that Wade’s turned up not only dead but murdered, Buddy’s the prime suspect. He was the beloved sheriff of Frontera once, succeeding Wade after he vanished. Most people in Sam’s position would want to bury the case, but Sam wants to know what happened. Part of him wants his father to be the killer, to take the shine off the indestructible legend. Always living in his father’s shadow, he wants to beam a light into that darkness.

Sayles’s own experiences hitchhiking along the border served as inspiration for Lone Star. He was struck by the border’s porousness, its fluidity. That the multicultural people who lived there seemed pretty happy to coexist, to cross back and forth regularly, visiting loved ones living just on the other side. It’s governments and their ugliest constituents who insist on the separation, supporting the narrative that cast border crossers as villains.

But the border’s history has been fraught with violence. Elizabeth Peña’s Pilar Cruz teaches her students about the ceaseless bloodshed there, like the Mexican War of Independence or the era following the Confederacy’s defeat, a time defined by range wars and race wars. At the end of her lesson, Pilar asks Eddie Robinson’s Chet, “What are we seeing here?” He’s distracted, drawing in his notebook, and he hasn’t heard a word. Yet he still knows the answer is “Everybody’s killing everybody else.” That’s how the story always goes.

These years of bloody conflict at the border don’t remain an abstraction in Lone Star. The film manifests them in the form of Charlie Wade; he’s not a baseless boogeyman, a bit of Hollywood hyperbole. The character sprang from real history of the Texas Rangers (or rinches), who were once infamous for their extrajudicial killings of Mexicans and Mexican Americans. At one point in time, they became as feared in the Southwest as the Ku Klux Klan were in the Deep South, essentially acting as death squads. Their cruelty earned them nicknames like los Tejanos sangrientos (bloody Texans) and los diablos Tejanos (Texas devils). Of course, the Rangers told a different story about themselves, crafting their public image as righteous protectors. Wade himself is a relic of that era of lawlessness, a vivid rendering of the kind of history we try to conceal but that won’t stay buried.

In a scene that still plays out in classrooms today, white parents rail against the truth being taught to their children. It’s another battlefield. One woman accuses them of “just tearing everything down. Tearing down our heritage, tearing down the memory of people that fought and died for this land.” Pilar explains, “I’ve only been trying to get across part of the complexity of our situation down here—cultures coming together in both negative and positive ways.” Another teacher says they want to “present a more complete picture,” and the irate white woman replies, “And that’s what’s got to stop!” But the kind of history she wants her children to learn is propaganda. Upholding that mythology helps those in power stay in power, preserves the status quo.

For Sayles, learning the real history of the Southwest fueled the making of Lone Star. He explained to Hammer to Nail: “I got to come down to Texas to do a little part in this movie Piranha I had written. I had a day off and I took a bus to San Antonio to actually see the Alamo. The day I was there, there was a protest march on the Alamo with Chicano people saying, ‘why don’t you tell the whole story?’” Delving deeper, he discovered the complexity of the battle. When they say “Remember the Alamo,” we only recall a tall tale about brave freedom fighters. We forget that not all the Alamo’s two hundred defenders were Anglo—many were Mexican and European. They didn’t all look like John Wayne’s Davy Crockett. And Mexico had outlawed slavery; one of the so-called “freedoms” the Alamo defenders were fighting for was the right to own slaves. But Pilar might say that’s an oversimplification, too.

Chet tells his grandfather Otis (Ron Canada), “My father says from the day you’re born you start from scratch.” But we all have to shoulder the weight of history, of everything and everyone who came before us. We omit certain truths from the Alamo legend because it means our heroes are fallible, human rather than superhuman. It might even mean they’re the transgressors in the story. And, based on our heritage, we define who we are. If our supposedly intrepid ancestors turn out to be less than virtuous, we start to question ourselves, as if our moral fiber is dictated by DNA. By investigating his father, Sam seems to wonder the same.

During Sam’s search, he heads down to Ciudad Léon to talk to Chucho Montoya at his tire repair shop. Chucho makes a line in the dirt with a Coca-Cola bottle and tells Sam: “Step across this line. Ay, que milagro! You’re not the sheriff of nothing anymore. Just some Tejano with a lot of questions.” Chucho asks him what he thinks of a bird flying south, delivering lines that feel Shakespearean: “You think he sees this line? Rattlesnake, javelina, whatever you got—you think halfway across that line they start thinking different? Why should a man?” A bird does not comply with a border; the animal exposes it as arbitrary, a human invention. No matter how strictly borders are enforced, humankind is borderless. Like it or not—and most of Frontera’s patchwork of individuals don’t—their stories are intertwined, inextricable. It’s in even the tiniest details of Lone Star, like what’s playing during the drive-in scene: Black Mama, White Mama, a movie about a Black woman and a white woman who escape from prison shackled to each other. As Sayles told Film Comment, “Even that [movie] is about people of different races being chained together whether they want to or not.”

Like Sam, Joe Morton’s Colonel Delmore Payne has returned unexpectedly to his hometown to head up the local army base. His relationship with his father, Otis, mirrors Sam’s and Buddy’s, except that Otis is still alive. What’s broken between them can be mended. Otis left their family when Del was a child to be with one of his mother’s best friends, and Del still resents him for it. His feelings are not shared, though—he explains to his wife that “everybody loved Otis. Big O. Always there with a smile or a loan or a free drink.” Dubbed the Mayor of Darktown, Otis became their small community’s protector; their affection for the man is understandable. Otis tells Del: “It’s Holiness Church or Big O’s. Most [people] choose both. You see, there’s not like there’s a borderline between the good people and the bad people. You’re not on either one side or the other.” Otis isn’t just talking about the people of Frontera but him and Delmore, because history and the stories we tell about our own lives are just alike. We’re compelled to tell them, always casting ourselves as the hero. Anyone we’re in conflict with becomes the villain. And that’s how Delmore perceives both his father and the world in general—to him, everything’s black or white, good or bad.

Del begins to soften after he sees his father again, especially when he realizes Otis has been keeping tabs on him. His father has a kind of shrine at his bar for his ancestors, the Black Seminoles, and one at home for his son Delmore. Del in turn eases up on his own son, Chet, a gifted artist who has no desire to go to West Point, despite the expectation he’ll join the army someday. But Del relents on that point, too. This evolution is unmistakable in his scene with Private Athena Johnson (Chandra Wilson) after she tests positive for drugs. Rather than meting out punishment, he has a conversation with her, listens to her. When Delmore tells her, “I’m just trying to understand how someone like you thinks,” he expresses the film’s raison d’être in a single sentence.

Lone Star plays out like a Raymond Chandler mystery, its plot just as byzantine. Sayles explains to The Reveal: “Raymond Chandler’s books were written by a British guy who’d been working in the US oil industry in Los Angeles and was fascinated and disgusted by American culture, and especially the low-level Hollywood angle of it. So his books are these wonderful tours through the Los Angeles of his time, and very often it’s not that important who killed who at the end. The detective story gets you to go to all these places and it gets you into race and politics and Hollywood and all those other things.” Like a Chandler novel, Lone Star’s whodunit premise is just an excuse to explore the contours of the Southwest, its atmosphere, its past, its residents. The mystery serves as the spine of its narrative, and who killed Charlie Wade is beside the point. It’s about each and every one of its characters; none of them is extraneous. And what at first seems to be separate strands turns out to be a knot. Whether these characters are in love or at war with each other, they’re connected. One big tangle. Those who are most hell-bent on building borders between them do so at the expense of their humanity.

Míriam Colón’s Mercedes Cruz has fashioned this kind of division within herself. She tells people she’s Spanish, not Mexican, suppressing her past out of fear she might lose her standing in Frontera, the success and prominence she has fought so hard to achieve. Her heart has ossified toward people who were just like her. When her employee Enrique (Richard Coca) asks her for help after his fiancée, Anselma, is injured crossing the Rio Grande, she threatens to call Border Patrol and complains, “Either they get on welfare or they become criminals.” But a flashback reveals that Mercedes once crossed that very same treacherous river. She met her future husband, Eladio, there when she was lost and he appeared with a lantern and an outstretched hand to guide her out of the darkness. Something about Enrique and Anselma unlocks this memory, reminds Mercedes of who she is, of her own young family. It resuscitates her essential humanity.

And this is what’s redemptive—not just about Frontera, but about humankind’s fraught tangle: the ways we take care of each other despite our unending battles and manufactured borders. It echoes what Sam says to his ex-wife, Bunny (Frances McDormand), after she tearfully tells him about a football player who can bench press 350 pounds. She finds it hard to imagine having that much weight on top of you, pressing down. But Sam explains, “I think they have another fella there to keep it off your chest. A spotter.” After Mercedes recalls what it was like to arrive in Texas, she decides to take Enrique and Anselma to a doctor who will help them for free, without getting the authorities involved. She helps keep the weight off their chests, just as Eladio did for her once upon a time.

Like Mercedes, everyone’s guilty of whitewashing their own stories, just as we whitewash the history of our ancestors, our communities, our countries. Lone Star is a cautionary tale about how a legend that may begin as celebratory, a source of pride, can curdle into something else, something destructive, reductive, false. History becomes more fiction than fact. But it shouldn’t be simplified, buried, distorted, embellished.

Which is exactly what the Western does. It mythologizes. Lone Star isn’t a neo-Western so much as it is a subversion of the genre. It’s almost a meta-Western, since the film begins with a man sifting through old bullets to transmute them into art, the same kind of magical, alchemical process that has sustained Western storytelling since the genre’s genesis. In his book Horizons West, Jim Kitses calls Westerns “odes to Manifest Destiny,” the imperialist dictum this country was built on. But Lone Star questions, critiques, raises its middle finger to manifest destiny. It dissolves the clarity of bad guys in black hats, good guys in white hats. And it upends the frontier myth, exposing it as another false narrative.

The frontier myth, according to the historian Richard Slotkin, depicts America as a “wide-open land of unlimited opportunity for the strong, ambitious, self-reliant individual to thrust his way to the top.” (Part of the myth’s poison is its affirmation of self-interest: once we arrive at the top, we neglect to lend a hand to those at the bottom.) It’s a story told and retold about the rugged white American heroes who tamed the wilderness and brought civilization to the uncivilized single-handedly. The American West has only ever been entirely white in the movies; the reality is more complex, more diverse. At the Gold Rush’s peak in 1852, twenty thousand Chinese immigrants came to California. And historians estimate that, after the Civil War ended, one in four cowboys was Black. There were Native American and Mexican cowboys, too—the culture, of course, originates with the Spanish tradition of the vaquero. The Western is a fever dream of the past, a shimmering mirage that vanishes with the merest touch. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance grapples with this, too. And Lone Star is John Ford’s masterpiece reimagined for the modern age, a thoughtful meditation on its most famous line, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

Buddy is a case study in this “print the legend” ethos. At first glance, he’s the Platonic ideal of the Texan, this blue-eyed golden Tejano cowboy in a white hat. It’s easy to believe in Buddy, to believe that he’s a paragon of justice. But he might just be a prettier, more socially acceptable Charlie Wade. He’s the only man courageous enough to stand up to Wade, insists he won’t be his bagman or accept bribes, but he’s just as guilty of enforcing borders and divisions; his prejudice is simply more polite. The bartender Cody (Leo Burmester) points out that Buddy would have issued a warning to Stephen Mendillo’s Cliff and LaTanya Richardson Jackson’s Priscilla when he sees the white man and Black woman sitting together at his bar, just as a “safety tip,” Cody says with nostalgia. Sam also finds out Buddy once used a prisoner for free labor to build a patio at his house. And after Buddy helped forcibly move and deport Mexican inhabitants out of Perdido, he benefited with property he bought there for a fraction of the market price. His philosophy of power was not unlike Charlie’s, he just exchanges favors instead of cash, an “I scratch his back, he washes mine” arrangement. Wade’s villainy is so outsized that it eclipses Buddy’s corruption.

But Buddy has done some good, too. Sam discovers that the truth of his old man is more complicated than he knew. Wade didn’t steal the missing county funds, Buddy did—to give to Mercedes, long before their affair began. Since Charlie killed her husband, Eladio, in cold blood, Buddy considered the $10,000 to be “widow’s benefits.” And when Jeff Monahan’s Deputy Hollis sees that Charlie’s about to shoot young Otis (Gabriel Casseus) in the back, he shoots Charlie first, just as Buddy enters the bar. Buddy helps them cover up the murder to protect Hollis because Charlie’s cronies will punish him harshly. Since then, Hollis has become mayor, and burying what happened is the right thing to do. Lone Star feels like it veers into horror whenever Charlie’s onscreen; Hollis vanquished a monster, a man who would’ve kept putting people in the ground with impunity.

When Sam hears what really happened, he makes the same choice his father did. There will always be suspicion cast on Buddy for murdering Charlie. But Buddy’s legacy can handle it, just as Sam can now let go of the burden of that legacy. He’s not the devil Sam believed him to be, nor is he the saint the community holds him up as. Even borders within our hearts are a fiction, a yarn we like to spin about how people can be only good or only evil. It’s never as clear-cut as we’d like. As Sam excavates the secrets of the past, this revelation feels more consequential than solving the murder mystery.

William Faulkner famously wrote, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Old sins cast long shadows. That’s in the bones of Lone Star, in its flashbacks that unfold without cuts, without dissolves. Our eye moves fluidly between a scene set in the present to one set in the past, a transition that is entirely, ingeniously in-camera. To Sayles, a cut is another border; the past is always in the fabric of the present.

Sam tells Pilar that he returned to Frontera only because she was there. The pair were like Romeo and Juliet once, lovestruck teenagers separated by their parents. In Sam’s eyes, this is Buddy’s gravest sin against him. But they learn the terrible truth: their parents kept them apart not out of cruelty but because they knew Buddy was Pilar’s real father. Like Oedipus, Sam emerges from his quest with primally devastating knowledge, the kind that’s dark enough to make a man stab his eyes with gold pins. It’s a truth as dangerous as the slumbering rattlesnake that Gordon Tootoosis’s Wesley Birdsong once found in a junkyard crate. “Gotta be careful where you go poking,” Wesley warns. “Who knows what you’ll find.”

But Lone Star tinkers with every genre it explores, and that includes undercutting Greek tragedy. Rather than blinding and exiling themselves, Sam and Pilar decide to stay together. To leave the past behind them, toss aside the sheriff’s star. When they visit the abandoned El Vaquero drive-in theater—the place where their parents once found them together and tore them apart—it feels like a haunted space, the site of some bygone war. But their story isn’t over yet. Both Sam and Pilar look at that old screen as if they might be able to see a new story playing out there. The blank screen is an artifact of their painful history, but it also offers a vision of their future, one they’ll write themselves.

Pilar says to Sam, “Forget the Alamo.” Lone Star concludes that both myth and truth have their place, and we each get to decide the sway they hold over our lives, how much the past determines our present. Like what Otis says: blood only means what you let it. And Sam and Pilar choose to unburden themselves. To begin again somewhere else. Though history might feel like a battlefield to them, in the present they can tend to old wounds and find some kind of peace. ![]()

Priscilla Page writes about cars, movies, and cars in movies. Her bylines include Empire Magazine, Hagerty, Autoweek, Fangoria, The Guardian, Bright Wall/Dark Room, and Polygon. She currently and eternally lives in Los Angeles.

Illustration: Tom Ralston.