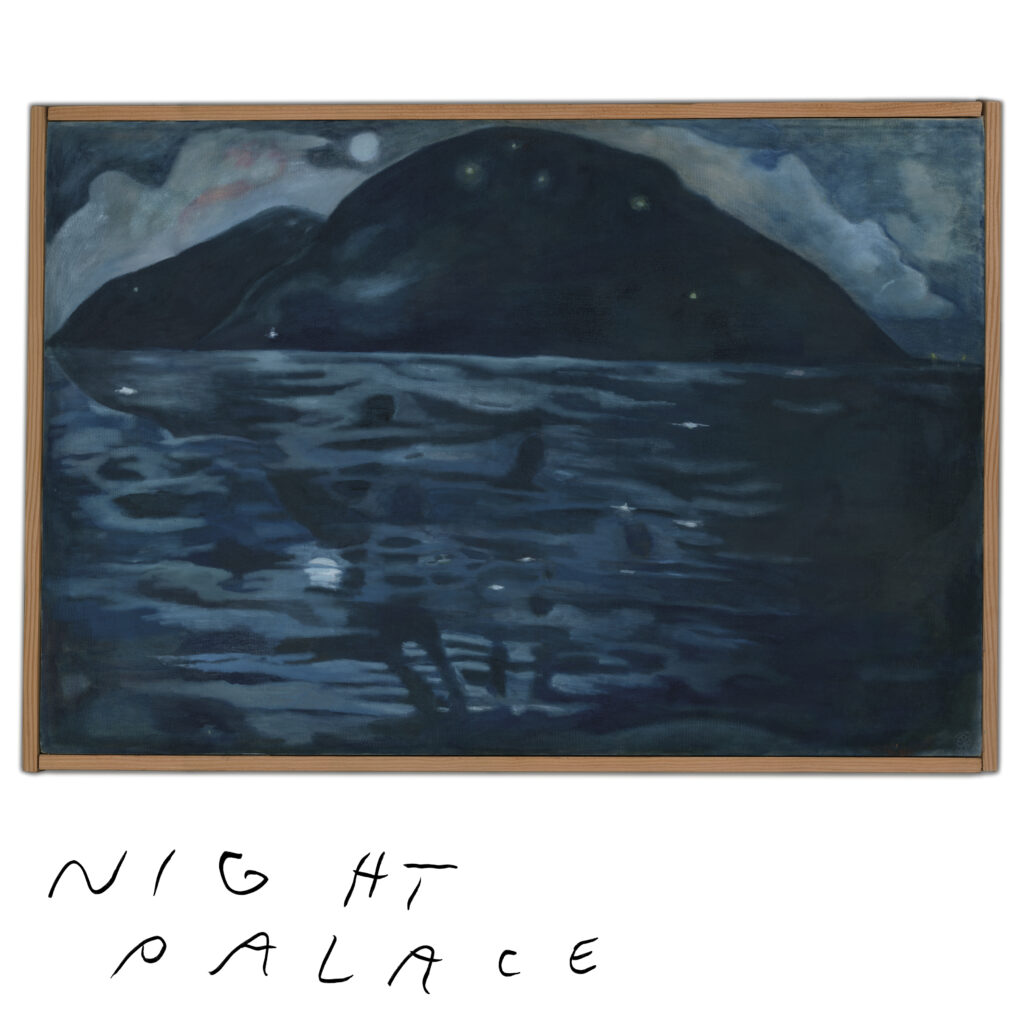

The Guest List is a regular book column that surveys the reading habits of our favorite musicians. In this edition, Emily McBride talks with Phil Elverum, best known for musical projects the Microphones and Mount Eerie. Mount Eerie’s latest album, Night Palace, was released in November via P. W. Elverum & Sun.

Emily McBride: Are there any books that inspired you while writing Night Palace?

Phil Elverum: Maybe the one that gets referenced the most is the old Zen Buddhist sutra by [Eihei] Dōgen called “Mountains and Waters Sūtra.” In four or five songs, I drew from the imagery and the ideas. That might be an overarching theme to all the songs: trying to get at what Zen is all about. It’s hard to summarize Zen, but that’s what I was reading. For the imagery, Dōgen uses these colloquial metaphors from Japan. For example, looking through a bamboo tube at the corner of the sky to illustrate having sort of a limited perspective. I have a song called “Empty Paper Towel Roll,” where basically I just translated his terminology into more modern imagery.

Phil Elverum: Maybe the one that gets referenced the most is the old Zen Buddhist sutra by [Eihei] Dōgen called “Mountains and Waters Sūtra.” In four or five songs, I drew from the imagery and the ideas. That might be an overarching theme to all the songs: trying to get at what Zen is all about. It’s hard to summarize Zen, but that’s what I was reading. For the imagery, Dōgen uses these colloquial metaphors from Japan. For example, looking through a bamboo tube at the corner of the sky to illustrate having sort of a limited perspective. I have a song called “Empty Paper Towel Roll,” where basically I just translated his terminology into more modern imagery.

EM: What else were you reading at the time?

PE: Night Palace has a trilogy of songs that are overtly political and speak to colonization and private property. I was curious where the roots of this weird situation we have with private property . . . where that came from in our culture, people’s extreme attachment to keeping other people off of the land that they think they own. I was reading this book called The Dawn of Everything, by David Graeber and David Wengrow. It made me reconsider this truism that I had heard and had been repeating for years, which is that [the origin of] humanity shifting to hierarchical organizations—with domination and stratification of society—was the development of agriculture. That’s what I’d always heard. And before that, we were just kind of nomadic and small—tribal, utopian, harmonious, maybe matriarchal. But I realized that truism that I had been repeating is so romanticized and wrong. It’s not borne out by archeological evidence, and actually, the history of humanity is more nuanced and complicated. It’s not this linear fall from grace. Which means that new, unimaginable ways of organizing society are actually possible in the future. It made me feel not so apocalyptic.

Then also I read this commentary on Karl Marx—this sounds so heady and academic, but I was trying to go back as deep as I could on this private property thing and where it shifted—and Marx, some of his early essays were about criminalization of wood gathering, like firewood gathering in Germany in the early 1800s. There’s a book called The Dispossessed: Karl Marx’s Debates on Wood Theft and the Right of the Poor, by Daniel Bensaïd, which is a commentary on Marx’s essay.

EM: Nature—both the stillness and the loudness of it—are huge themes in a lot of Mount Eerie. Are there any authors who see or describe nature in ways that you relate to?

PE: I feel like my relationship with the idea of nature is . . . I’m a little grumpy about it. I feel almost resistant to naming it. I really like Gary Snyder, who is often thought of as a nature poet. I like almost all of his work, but maybe my top recommendation would be his collection of essays called The Practice of the Wild. He says there is no separate nature, even though we often think there is. The spiders that live in our houses, in the middle of cities, all the bacteria that lives in our body. Everything is permeable and wild at the same time. That’s an angle that resonates with me.

EM: What are you reading now?

PE: I just started a Joni Mitchell biography that I got at the library yesterday called Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell, by Ann Powers. It’s too early to tell if it’s going to be influential on me. I love Joni Mitchell, and I just don’t actually have the background information. I don’t usually read rock bios or bios at all, but she’s special.

Actually, there are a couple other biographies that I’ve read in recent years—so maybe I do read rock bios. The Amplified Come as You Are: The Story of Nirvana by Michael Azerrad, I tore through that. It was a similar thing where I didn’t have all the details of the story. Of course I really love Nirvana, but I was never drawn to the tabloid-y aspects. The annotated book, however, was really fun to read. I was fourteen when Nevermind came out, the exact right age for it, and it changed my life. It changed lots of people’s lives and made them realize that regular-looking people could make cool music. Instead of just famous-looking people. The book also gave me some context, because I lived in Olympia. I spent time in a lot of the same places and knew a lot of the same people as Nirvana but, you know, ten years later. It’s so close to home, and my worldview. The bio brings them back down to earth, even though they were mega-famous superstars.

And then there’s the great David Lynch autobiography called Room to Dream. His devotion to the art life is so inspiring. Getting successful, turning away from safe choices and turning toward artistic integrity. That’s what I got out of his book.

EM: We’ve talked about biographies, poetry, philosophy. Are there other genres that you are drawn to?

PE: I’m all over the place. I read some fiction. I just finished a short Norwegian novel by Jon Fosse called Boathouse. It’s told in the voice of a nonwriter. The narration is written in stream of consciousness with long, run-on sentences. And so you piece together the plot through the narrator’s crude, unformed thoughts. The point where it coalesces and you realize what’s happening is such a beautiful moment. I’d read Fosse before, and now I want to read more of his books.

EM: You have dealt with tremendous loss, I’m sorry to say. Are there any books that helped you through the loss of your wife?

PE: The first thing that jumps to mind is another one by Gary Snyder. A long poem called “Go Now” and it’s about his wife dying. It’s pretty gory in a way. He describes her face changing as she gets sicker, and then she dies. He describes taking her to have her cremated and the smell of the place and how intense it all is. But what makes the poem so good is he ends it by saying, “—this is the price of attachment— / ‘Worth it. Easily worth it—’” That was helpful for me. I’m not inclined to euphemizing death and grief. I just want to look right at the thing. So that poem really worked for me.

EM: Any other books you’d like to shout out?

PE: Next on deck is Karl Ove Knausgaard’s novel called The Wolves of Eternity. He’s one of my favorite writers, and it’s part of a trilogy. I already read the first one, and this is the second. I read his humongous three-thousand-page novel My Struggle, volumes 1–6. That took some years of my life. It changed the way I thought about my life, about my writing, about mundanity and significance in life. It’s tough to describe. They are extremely powerful novels. Now he’s writing, I think, a trilogy of fiction about some kind of Biblical end-of-the-world stuff in Norway. I like reading Norwegian novels and I don’t know why. I’ve been there a few times and for extended periods, so it’s probably easy for me to place myself there when I’m reading. I like to hang out in Norway in my mind. ![]()

Phil Elverum released records as the Microphones with the K label, including 2001’s seminal The Glow Pt. 2. Since 2003, he has operated under the moniker Mount Eerie and released albums on his own record label, P. W. Elverum & Sun. His devotion to a life of creativity has never wavered, and in 2024, he released his sprawling double album Night Palace.

Emily McBride is a music writer, previously serving as an editor at Paste and YouTube Music, as well as a freelance contributor to Consequence and Noisey. She currently resides in Portland, Maine, and is on a lifelong quest to find the perfect michelada.