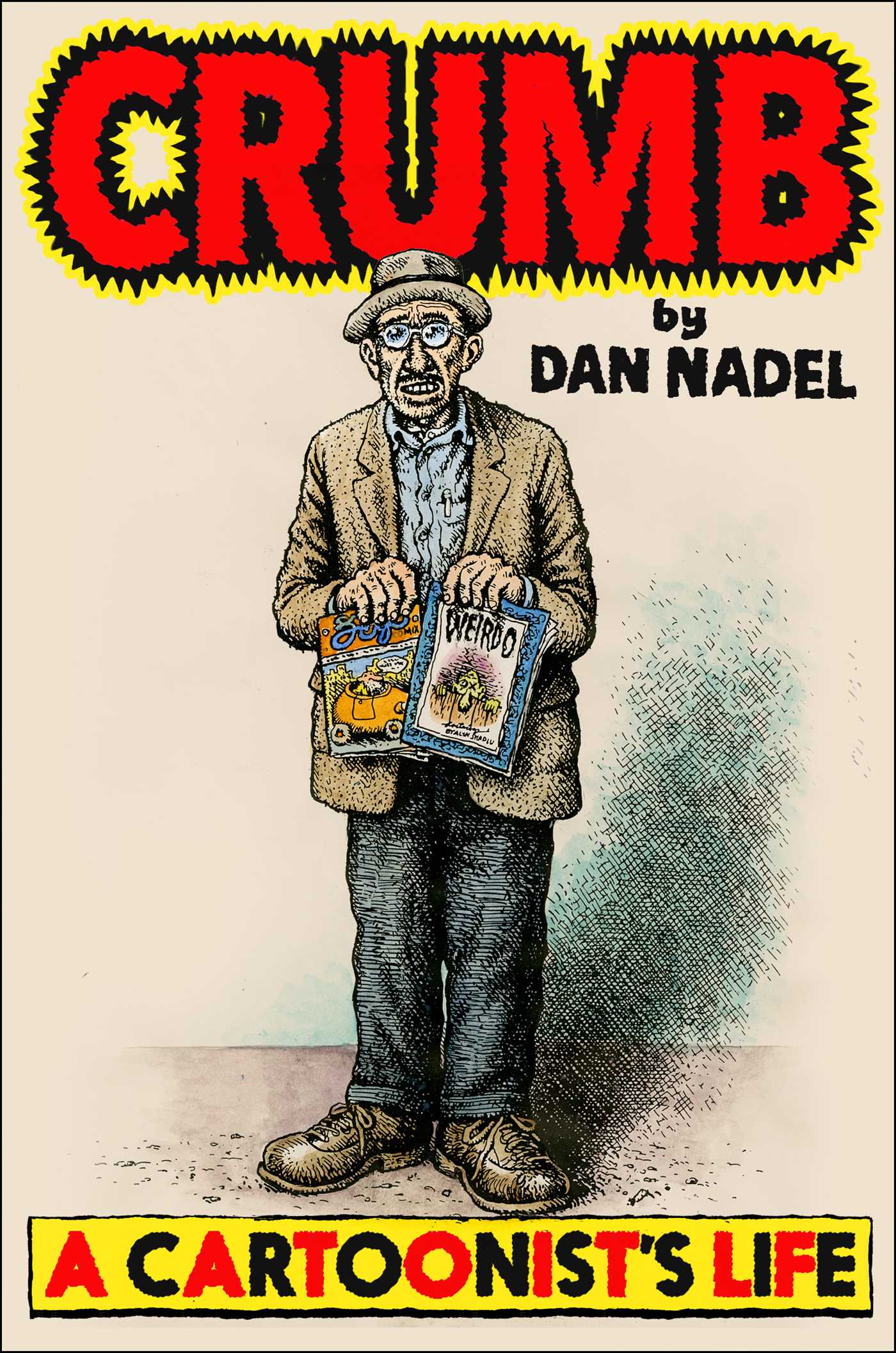

The cartoonist Robert Crumb was born in 1943, which he once observed was “the bloodiest year in the history of mankind.” Crumb was making no idle connection. Violence was Crumb’s birthright—both geopolitical carnage and more tawdry but still traumatic domestic abuse. This violence has marked his work and is one of the sources of its discomforting power, its ability to offend and shock even as it speaks to pervasive (if often taboo) human experiences and emotions. As Dan Nadel makes clear in his new biography, Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life (2025), Crumb survived intense familial pain but has never been entirely free of the patterns of maltreatment that were implanted in him so early, which he triumphantly grappled with in his art but sometimes sadly replicated in his life.

Robert’s father, Chuck Crumb, was an abusive patriarch of a brood of tormented geniuses who organized his life around an alternating pattern of parenthood and slaughter, creating and destroying life as the season demanded. In 1936, Chuck, a twenty-two-year-old schoolteacher with dreams of becoming a globe-trotting adventure novelist like Jack London, enlisted in the Marines. The following year he participated in fierce fighting that led to three hundred thousand deaths in Shanghai, where the Marines were stationed to protect the International Settlement while Japanese imperialists and Chinese nationalists fought pitched battles for the future of China. In 1940, on a stateside tour as a recruiting warrant officer sergeant in Philadelphia, Chuck met a waitress named Beatrice (Bea) Hall, who he in short order romanced, impregnated, and married. Only twenty, Bea already had a complicated family history: when she was fourteen, she started a sexual relationship with a stepbrother who was a year younger. This incestuous union led to a secret child, Catherine, who Bea’s mom raised as her own, a disavowed daughter transformed into pretend sister. As Robert Crumb would observe, his mother’s family was “urban, a bit lumpen, dissolute, alcoholic, degenerate. Sexual weirdness, all that stuff.”

The rhythm of Chuck’s adult life was family and flight. Bea gave birth to Carol, her first child with Chuck, in 1941, followed by Charles Jr. in 1942 and Robert in 1943. Soon after Robert’s birth, Chuck was assigned to the Fleet Marine Force Marine Bombing Squadron. In 1944 he reunited briefly with Bea for long enough to sire another son, Maxon. Then he fought in two of the great bloodbaths of the Second World War, the Battles of Saipan and Okinawa. He returned to America and fathered one last child, Sandra, born in 1946. However, he wasn’t done with war; he rejoined the Marines as part of a show of force in the Pacific designed to shore up the crumbling nationalist government in China. In the early 1950s, Chuck was eager to fight in the Korean War, but the military, in a surprising display of sensitivity, took notice that his “nervous” wife was hurt by his long absences. Even after he ended his active military career in 1956, Chuck would take multiple jobs to avoid homelife. He created a family but didn’t want to be bound by it.

This absentee fatherhood was, as the psychologists say, overdetermined. As a gung-ho Marine, Chuck found little in common with his three sons, who were all hypersensitive and aesthetically inclined, and who otherwise eschewed traditional masculinity, let alone the hypermacho version embodied by their dad. Chuck’s bullying and physical abuse failed to turn these sissies into men. Chuck’s own showy virility might have itself been a disguise—a gay friend of the Crumb brothers once spotted Chuck at a public toilet that served as a cruising spot, where the former Marine showed familiarity with the codes of secret assignations.

Chuck wasn’t the only violent parent. Bea, addicted to various drugs including diet pills and amphetamines, would sometimes claw her husband’s face or threaten suicide. She was occasionally institutionalized and at least once received electric shock treatment. All the Crumb siblings bore the mark of their childhood. The Crumb sisters suffered from alcoholism, family alienation, and betrayal. Maxon, also a gifted artist with a grotesque bent, was an untreated epileptic. He twice went on violent rampages against women.

Amid the strife of their parents, the Crumb children retreated into a secret life, a sibling commune built around comic books. Charles was the ringleader despite being the second child—a willful impresario with a passion for Dell comic books featuring Donald Duck (created by the then-anonymous Carl Barks, a master storyteller who brought the brio of a Robert Louis Stevenson to the funny pages) and Little Lulu (spearheaded by another uncredited virtuoso, John Stanley, whose irony-rich dialogue sparkled like a Preston Sturges script). All the Crumb kids drew comics, but Robert was the one who stayed at it longest, animated not just by Charles’s brotherly browbeating but also by his own passion for the form. The ability of comics to distill human emotions into iconic forms and immersive narratives spoke to Robert. This, after all, was a child who had early sexual fantasies involving Bugs Bunny as well as the more socially acceptable Sheena, Queen of the Jungle (a TV character, adapted from comic books, who was the prototype of the muscular Crumbian Amazons who would populate his adult drawings). As Charles and Robert filled endless pages with their home-drawn funny animal and satirical comics, they internalized the ability of Barks and Stanley to charm readers with an inviting interplay of words and images. Within a few years, Harvey Kurtzman, the satirical mastermind behind Mad comics, would offer further lessons in visual storytelling, the special patter of parody, and the ability to transition smoothly from the mock grandiloquence of ridiculous pratfalls.

Comics saved Robert Crumb’s life. They gave him a way to escape, although never in any unwounded form, from his parent’s dark legacy. But comics couldn’t do the same for Charles. Viewers of Terry Zwigoff’s 1994 documentary Crumb will remember the vivid scenes of Charles, the erudite but trapped brother, his mind foggy from drugs but still burning fiercely, who lived with his mother until his suicide in 1992. Nadel fleshes out this portrait by showing how much Charles was Robert Crumb’s shadow self, the wellspring of creativity but also the tragic path avoided. Charles was gay but never able to form a relationship; his thwarted sexual imagination took a pedophilic cast, as he admitted in letters, although he prevented these impulses from leading to outright abuse. By refusing to leave his parent’s lair, he perhaps thought he was doing the world a service.

Despite this dismal background of family dysfunction, Robert Crumb’s own life is a triumph, albeit with many shadows. Thanks to the cartooning skills he honed in childhood, he left his parents in 1962 at age nineteen, finding work at the American Greetings card company. Starting as a lowly color separator, he quickly rose to star artist, valued for creating cards that brought a sly bohemian edge to an industry trying to win over the burgeoning youth market. In Cleveland, aided by hip friends like the writer Marty Pahls, who shared Crumb’s taste for reclaiming the lost popular culture of the past, the shy and virginal Crumb even started making inroads with women. As his father predicted, Crumb in 1964 ended up marrying the first girl who had sex with him, Dana Morgan, who was round and zaftig in exactly the manner of the female fantasy characters in the comic book stories that he was drawing in his sketchbooks.

Living in the liminal time between beatniks and hippies, Crumb and Morgan experimented with drugs, taking LSD (then legal) in 1965. Psychedelics were crucial in Crumb’s aesthetic evolution, breaking down his acceptance of consensual reality and opening his emotional and visual register to the primordial and the outlandish. Acid seemed to give Crumb a direct pipeline to his id. His cartoon characters like Mr. Natural and Fritz the Cat could be as cute and rounded as the denizens of a Disney comic book, but they engaged in sexual antics, metaphysical mind games, political subversion, and emotional outbursts far beyond anything Mickey Mouse or even Donald Duck would ever do, at least in officially licensed property. (Later, the cartoonists in the Air Pirates cabal, taking courage from Crumb’s examples, gave the world an erotically energetic Mickey Mouse).

As he started to flower in the mid-1960s, Crumb was both deeply conservative and terrifyingly radical. He was conservative in his deep grounding in the form of comics. Like Barks, Stanley, and Kurtzman, Crumb had a total mastery of visual storytelling: his comics drew you in, populated by iconic figures with their own distinct gait and lilt, and, although breezy reads, had layers of meaning that rewarded many revisits. Beyond the cartoonists of his youth, the autodidactic Crumb became a deep historian of popular culture, his art nursed by a root-and-branch familiarity with the long line of low-comedy satirists that runs from Pieter Bruegel the Elder to William Hogarth to Thomas Nast to George Herriman (creator of Krazy Kat) and E. C. Segar (creator of Popeye).

Crumb’s conservatism manifested itself in his care for form, his radicalism in his content. While he borrowed from artists in the past, Crumb’s revolutionary underground comics (starting with Zap Comix in 1968) ruthlessly spoke to the turmoil of America in its time, a nation torn apart by a criminal imperial war abroad, a long overdue reckoning with its racist history, and emerging social movements challenging long-held sexual and gender norms.

In grappling with hot-button topics, Crumb opened himself to much criticism. In his comics of the 1960s and early 1970s he often turned to by then taboo minstrel show and blackface imagery (most memorably and notoriously in the character Angelfood McSpade) out of a mix of motives, some more justified than others. These minstrel images had the power to shock and were powerful explorations of the covert and creepy libidinal impulses behind racism. What made them suspect to many critics, as with the sexual imagery of Crumb’s curvy women, is that the artist is clearly enjoying what he’s drawing; he’s implicated in the very racism and sexism he’s offering up for criticism. Yet to my mind, this fact makes Crumb’s work all the stronger and more valuable—in exploring the darker side of humanity, he’s not finger-pointing at others but taking us on a journey through his own—and America’s—troubled soul.

Crumb has been candid about his own racism and sexism, admitting that he’s been a “‘male chauvinist’ asshole” who in the 1970s leveraged his fame to be a sex pest (his preferred transgression being jumping on large women for piggyback rides). His explorations of his own kinky sexual fantasies are also, I’d insist, a public service: they’ve made many readers, men and women alike, feel more at ease with their own heterodox sexual imagination and desires.

Crumb’s work took a nastier turn after the initial hippy bounciness of the first two issues of Zap. Partly out of the influence of fellow underground cartoonist S. Clay Wilson, a master of gleeful depravity, Crumb started conjuring up images of sexual assault, domestic violence, incest, and child abuse. Thanks to Nadel’s biography, we can better understand that Crumb wasn’t just engaged in titillation, exploitation, or personal self-indulgence. Rather, he was wrestling with the history of his family.

While Crumb escaped from much of the blight of his family life, the victory wasn’t total. Crumb’s first marriage to Dana Morgan wasn’t happy; his union in 1978 to the cartoonist Aline Kominsky-Crumb was much more successful. In both marriages and in other long-term relationships, Crumb displayed the family-and-flight pattern he learned from his father: he would fall in love with a woman but then get itchy feet, have affairs, or run away for weeks at a time. Nadel notes the “internal confusion” that ran through Crumb’s relationship with Dana, where Crumb “wanted a mommy but not a wife. A sexual partner but not a relationship. He wanted a home but no responsibilities.” This inability to commit not only destroyed the marriage but also did lasting harm to their son, Jesse. As with Chuck Crumb, absentee fatherhood took its toll—Jesse grew up to a troubled manhood bedeviled by recrimination and substance abuse leading to an early death. Crumb had an open marriage with Aline Kominsky-Crumb and was a much more hands-on parent to their daughter, Sophie. The results were much happier, but not free of occasional turmoil.

This family-and-flight pattern mirrored Crumb’s love/hate relationship with his audience. Crumb’s art is warm, homely, quirky, surrounded with a nimbus of cuteness. These qualities have won him a vast, appreciate worldwide audience. But uncomfortable with the forced and phony intimacy of fame, Crumb persistently sought to alienate this audience by putting his endearing images in the service of vile antisocial impulse. In a sketchbook note written in 1974 or 1975, Crumb reflected that his subconscious gave him ideas whose “time has come” but “when they love you for it, make a hero out of you and interview you to death, you (me) over-react and start drawing socially irresponsible and hostile work which you (I) then feel guilty about. The relationship between cartoonist and his public is a complex one.”

Crumb kept challenging himself. Beyond the famous work of the 1960s and early 1970s, he rejuvenated himself in the mid-1970s when he gave up LSD and started working with his second wife. Kominsky-Crumb, who died in 2022, was a master of autobiographical self-mockery. She teamed up with her husband to do comic books where each would write their own dialogue, leading the ping-pong banter of a comedic duo. Crumb also partnered with Harvey Pekar for gritty and piquant stories about working-class Cleveland. Another form of collaboration were the many literary adaptations Crumb did in this era, giving visual life to writers ranging from James Boswell to Philip K. Dick to Franz Kafka to Jean-Paul Sartre, culminating with the ultimate author, Jehovah, in The Book of Genesis (2009). Throughout his life, Crumb has repeatedly found a path to artistic rejuvenation by returning to childhood interests and practices. In the case of his adult collaborations, he was replicating the comics club that Charles had started decades earlier.

In addition, Crumb has done biographical comics about blues musicians such as Jelly Roll Morton and Charley Patton, loving and obsessively researched explorations of a forgotten America. (Nadel is a strong partisan of this later Crumb, the best of which he’s collected in the forthcoming anthology Existential Comics. This smartly curated collection gives us Crumb at his most respectable and presentable, which might make a good introduction, although many of us will miss the psychedelic wild man who dredged up marvels from the darkest crevices of his psyche.)

Although there have been great cartoonists for centuries, Crumb was the first who made the naked and fearless examination of such private issues the core of his art. This ignited a revolution that we are still living through. Comics, once a commercial form largely geared toward children or family-friendly entertainment, became a terrain for personal exploration. In 1967, Art Spiegelman, then a nineteen year-old fledgling cartoonist, saw the early pages of Zap in Crumb’s apartment before they had been printed. The experience changed Spiegelman’s life. As he recalls,

I realized I needed to change my goals in the world. I decided I was going to become a Buddha because comics were going to be fine without me. When I went back to drawing comics, Crumb had set me back a lot. Every cartoonist has to pass through Crumb. What happens when you encounter Crumb is like the accelerated evolution scene in 2001. You had to pass through him to find out what your voice might be. Crumb was radical art: he embodied the idea that comics would be a form of personal expression instead of a venue in which you might put in some personal material.

As Nadel documents, countless artists around the world for decades—everyone from Lynda Barry to Nicole Eisenman—have had the same experience with Crumb. His work inspired them to recalibrate their ambitions. Certain artists are not just talented, they are infectious; just as Bob Dylan made many singers, Richard Pryor made many stand-up comedians, Frida Kahlo made many painters, Robert Crumb made many cartoonists. I myself was infected with the Crumbian virus the first time I saw a Fritz the Cat story when I was thirteen. Although I had no artistic aptitude, I suddenly started sketching comics in my notebook. For me, this bout of the Crumb epidemic was short lived, although it sparked a lifetime of passion for the art. For many others, once they catch the Crumb bug, cartooning becomes their destiny.

Nadel’s biography is superb. He’s a strong advocate for Crumb the artist without having any illusions about Crumb the man. Nadel is clear-eyed about both Crumb’s achievements and his failures. Delving into painful family secrets, Nadel is generous in his empathy and clear in his moral discernment, avoiding the simplifications of tabloid sensationalism. And Nadel is almost as steeped in the history of comics as Crumb himself, which allows him to celebrate the art with a level of textural acumen that is rare in criticism. This is a book where you’ll learn the difference it makes to your penwork whether you draw with a crow quill or a radiograph.

Nostalgia is one of Crumb’s central thematic concerns, but it’s never an easy, placid enjoyment of past pleasure. Rather, nostalgia for Crumb means grappling with our cultural inheritance in all its complexity and pain, a nostalgia that doesn’t erase the minstrel show from the musical history of America. Crumbian nostalgia is the awareness that, for good or for ill, we can never escape the past, because it’s what makes us who we are.

Jeet Heer is a national affairs correspondent for The Nation and host of the weekly Nation podcast The Time of Monsters. The author of In Love with Art: Françoise Mouly’s Adventures in Comics with Art Spiegelman (2013) and Sweet Lechery: Reviews, Essays and Profiles (2014), Heer has written for numerous publications, including The New Yorker, The Paris Review, and The New Republic. With Chris Ware and Chris Oliveros, he has coedited the Walt and Skeezix series reprinting Frank King’s Gasoline Alley comic strip. He has also written introductions to many books of comics, including the works of George Herriman, Harold Gray, and Milton Caniff.