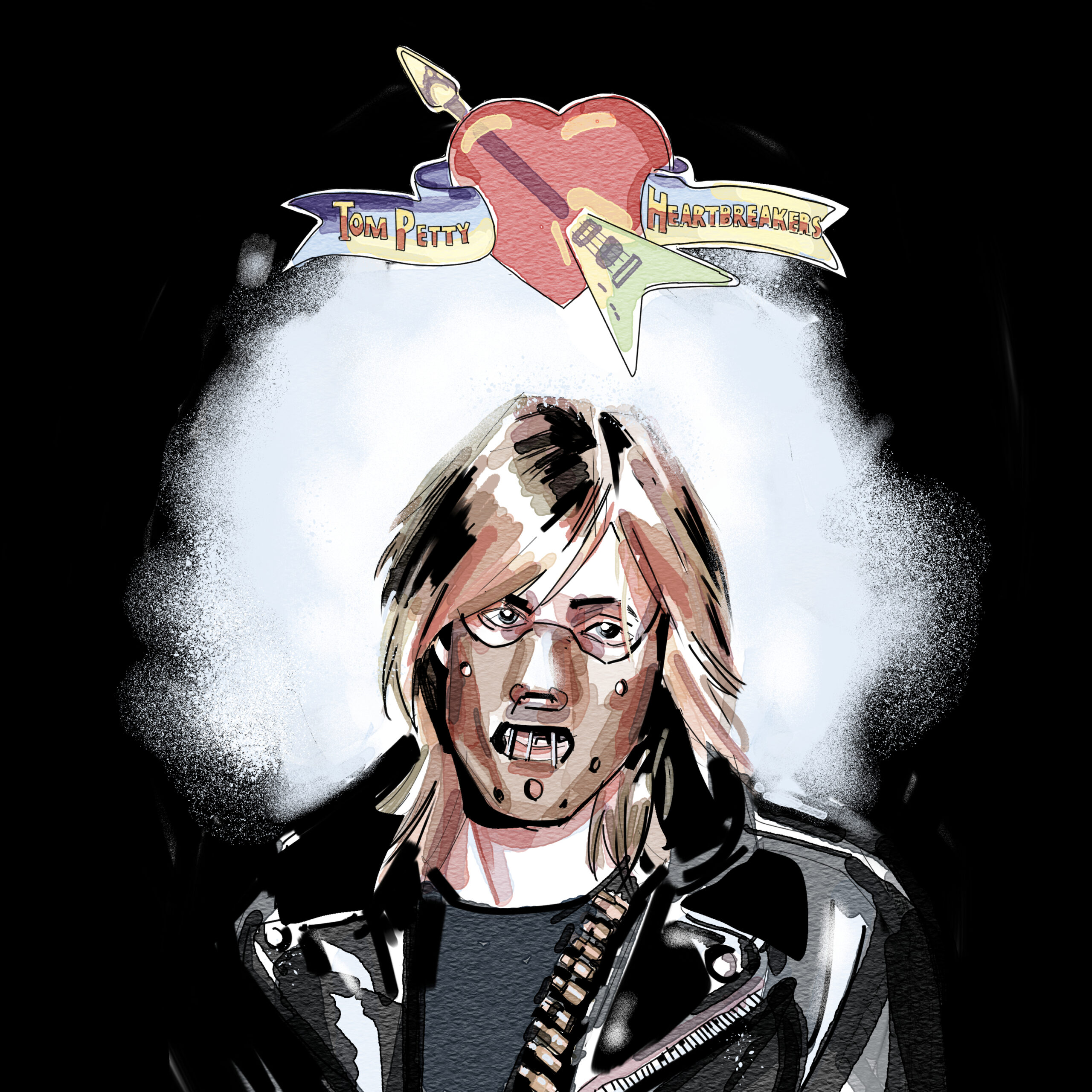

Needle Drops is a new column that asks writers about—you guessed it—their all-time favorite needle drop in a film. In this inaugural edition, Kimberly King Parsons talks about Tom Petty’s “American Girl” from Jonathan Demme’s seminal 1991 serial killer movie, The Silence of the Lambs.

Most people think the iconic needle drop from The Silence of the Lambs is “Goodbye Horses”—you know, that weird, ethereal track playing while Buffalo Bill does his now-infamous “would you fuck me” dance, accompanied by his impressive dick-tucking routine. It’s become shorthand for creepy cinematic moments, a cultural touchstone that most people can reference even if they’ve never seen the movie, a musical interlude that makes you simultaneously laugh, cringe, and want to shower for a week.

Though Q Lazzarus’s song has been dissected, memed, and discussed ad nauseam, Tom Petty’s “American Girl”—the song that Catherine Martin happily belts as she’s driving down the highway, unaware she’s being targeted by Buffalo Bill—is the needle drop that haunts me. Where “Goodbye Horses” is a moment of cross-dressing shock (that hasn’t aged well, I might add!), Petty’s track highlights that brief interval of calm just before everything tilts into terror. It is a devastating use of the song, deliberately ironic with its feel-good pep. It turns an anthem of resilience into something far more sinister: the precise moment when American optimism meets its own limitations, when hope and horror occupy the exact same sonic space.

I was only twelve when my mom—part hurricane, part middle finger to conventional parenting—pulled me out of school for the day to watch Jonathan Demme’s dark, wildly entertaining feature full of serial killers, cannibalism, skin suits, hardcore forensics, and the aforementioned dick-tucking. She did this after second period and under the guise of a dentist appointment, to my total delight.

As a mom myself, I now see this for the odd parenting choice it was, but at the time I just felt lucky. My mom is pure spitfire. She once smuggled a hermit crab onto an airplane in her bra against the strict orders of the TSA, and she has never cared much what you or I might think about her. She has always done exactly what she wants to do. Sure, I might have missed a math test, but I got an entirely different kind of education at the movies that day—one that would give me nightmares for literal years. But first, before the unfolding scenes of psychological torment, was Tom Petty singing about highways and hope. Even as a child I could hear it: that place where optimism meets quiet desperation.

Petty wrote “American Girl” in 1976 from his California apartment, but the song’s heart beats pure Florida—Gainesville specifically, Petty’s hometown. The track paints the perfect scene: a restless young woman on a balcony near Highway 441, watching headlights streak past below, caught between who she is and who she wants to be. It’s pure American DNA—that mix of determination and disappointment, of dreams rubbing up against reality.

There’s a persistent urban legend that the song is about a University of Florida student who died by suicide after jumping off the Beaty Towers dormitory, though Petty always denied this, stating that he wrote the song long before he’d even heard about that tragedy. The real story is simpler and more universal: it’s about that moment when you realize all those promises America made might not pan out exactly like you thought, but you keep believing anyway. Our girl stands above the highway, watching lives rush past below, somehow maintaining hope even as reality starts to crack the fantasy.

“American Girl” has been my go-to karaoke song for years, and this is the part where everybody always freaks out and screams along: “Take it easy, baby,” and then that iconic, echoing line: “Make it last—make it last all night.” What is Petty trying to get our American girl to savor? The sex? The drugs? Both, is my guess.

The opening guitar riff was allegedly inspired by the sound of cars passing by on the freeway outside Petty’s apartment near the 101. Hearing cars like ocean waves—a metaphor so perfectly American it hurts. The song captures that moment when youthful optimism slams face-first into life’s complete and utter bullshit. “Raised on promises”—isn’t that the most American line ever? We’re all just driving down some metaphorical highway, singing along like everything’s fine while the real world is about to snatch us.

Catherine’s behind the wheel, singing along like any other night, completely unaware she’s driving straight into horror. Where Petty’s original dreamer stands above the highway thinking about possibilities, Catherine’s about to have her own American dream ripped away. It’s genius how Demme flips the song’s meaning: that bright, hopeful melody becomes something so very bleak. The whole scene works because we know what Catherine doesn’t: that sometimes being an American girl means walking into danger without even knowing it. That upbeat guitar riff turns into a warning signal, a reminder that optimism can’t always save you.

The song serves as a pivot point between two versions of America: the hopeful, promising one of Petty’s lyrics, and the darker underbelly that Clarice Starling must navigate throughout the movie. Catherine and Clarice are each a different kind of American girl—one becomes a victim of shattered optimism; the other channels that disillusionment into the determination to protect others. I think about Catherine Martin driving alone at night, about Clarice Starling facing down monsters, about my own mother’s fierce disregard for convention. I think about how we all navigate the gap between the America we’re promised and the one we actually get.

The geography of both moments—Petty’s dreamer on the balcony and Catherine’s doomed drive—creates a perfect symmetry. Each woman occupies a space of transition: one above the highway contemplating her future, the other on it, moving toward an unseen destination. The song bridges these narratives across time and medium, speaking to something fundamentally true about American girlhood—its promise, its peril, the thin line between the two.

My mother—queen of giving zero fucks—understood this intuitively: some of us fight back, some become victims, but all of us have to navigate a landscape that’s equal parts hope and terror. The highway continues. The music plays on, and we sing our way through whatever apocalyptic shit comes next.

Kimberly King Parsons is the author of the national-bestselling novel We Were the Universe, a pick for Dakota Johnson’s TeaTime Book Club that The New York Times calls “a profound, gutsy tale of grief’s dismantling power.” Parsons’s debut collection, Black Light, was longlisted for the National Book Award and the Story Prize. Parsons lives with her family in Portland, Oregon, and teaches fiction at Pacific University.

Illustration: Rachel Merrell