What Was Found and Who Was Lost

Reviews

By Justin Peter Kinkel-Schuster

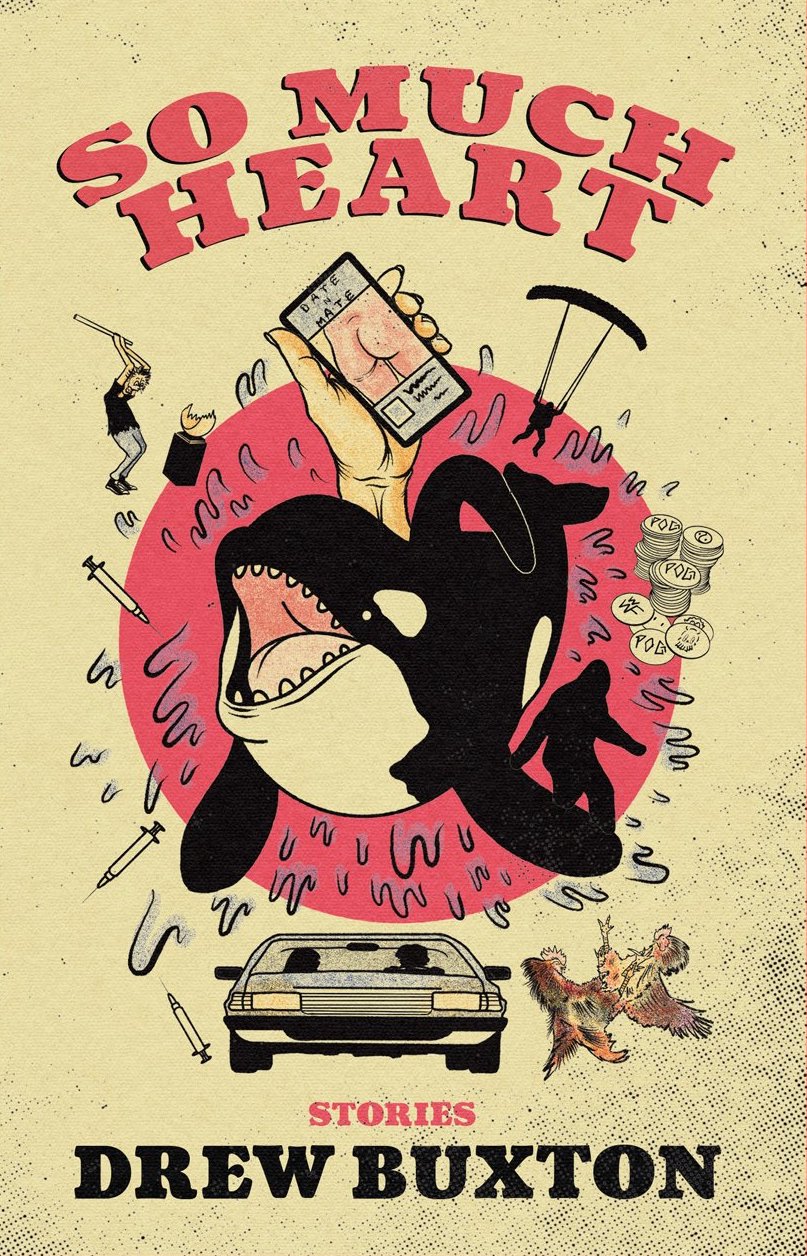

“We’re gonna find one, mom—I know we will.” So says Collin, the middle-school aged narrator of “So Much Heart,” the title story in Drew Buxton’s new collection. He’s referring to Bigfoot, the notorious cryptid of North American legend. His mom, hobbled by a broken leg of unknown origin, is obsessed with capturing Bigfoot on film, sending Collin into the Oregon woods with a Canon camera and her hazy dream fueled by beer, Moon Pies, UFO Magazine, poverty, and loneliness. What Collin finds instead is the dead body of another legendary figure, D.B. Cooper, along with Cooper’s ransom. Shocked but savvy enough to keep the cash (and Cooper’s body) secret, all Collin wants is for his mom to use a meager sum pilfered from the corpse to buy him a bike for Christmas. What she buys instead are two sets of high-tech night vision goggles to aid in their sasquatch hunt. The note of deep sadness, driven by inescapable love, that hums beneath the confidence in Collin’s words acts as a sort of deep pedal tone throughout the entire collection.

So Much Heart is populated by ordinary people on the verge; of society, of sanity, of discovery, and of loss, often all at the same time. They’re searching, seeking, looking for a chance, an angle, a root extending from the edge of a cliff like a cartoon character who’s unknowingly stepped off the edge—anything that might afford them access to the larger world of success, money, and the dreams they’ve been sold by a fundamentally weird, fucked-up culture. What makes these stories truly special—what turbocharges them—is their departure from realism into bent and refracted versions of past, contemporary, and future Americas.

“Tilikum Gets Loose” is a haunting story in which the narrator’s job at America’s last remaining Seaworld turns catastrophic. Protestors, once peaceful but increasingly militant and violent, blow up the tank that holds Tilikum, the orca known for killing trainers (as documented in the film Blackfish). Impossibly, torn bodies begin appearing in the nearby river and the narrator, Bo, suspects Tilikum (or Tilikum’s vengeful spirit) is responsible. Meanwhile, Bo has agreed to help his old friend and drug dealer Cassie search that same river for her sunken stash. Everyone is broke in this world: Bo, Mary (Bo’s girlfriend), Cassie, the park, the cops. Desperate for a cut of the spoils from Cassie’s wrecked car and driven by aural hallucinations of Tilikum summoning him to the river, Bo allows ghosts to converge. Wondering why Tilikum stays, menacing, Mary says, “He’s not getting vengeance on the right people, the higher-ups, the masterminds.” Will he, will any of us, ever? And would it be worth it?

In a book replete with deeply sad scenes made palatable by absurd humor and moments of unexpected sweetness, “Monticello” reigns. In it, Dessie is a diminutive drug kingpin who rules his elementary school with his wits and the opiates he conjures from poppies grown at home and processed on school grounds. At first, Dessie is his father’s right hand, but after his father’s death by overdose he’s forced to assume control. In order to stay out of the clutches of Child Services and keep his operation functioning, he enlists his teacher (and his father’s former lover) to help him bury the body in the backyard. Dessie tells her not to pray, insisting, “He doesn’t want that. He hates all that stuff.” But moments later, Dessie describes his father’s manifold thoughts on death and being reunited with Dessie’s mother, to which his teacher and abettor replies, “But I thought he didn’t believe in an afterlife like that.”

Dessie, whose voice throughout is preternaturally calm and strong, simply replies: “I know. But yeah. Sometimes he did.” Dessie’s understanding that both things can be—and are—true at the same time strikes me as both hard-won and convincing, especially given his seemingly impossible position. But Dessie’s ability to subsume his grief is not infinite, and we see him gradually bent (if not ultimately broken) by the pressures of his office. He retreats to the playground and takes refuge in the swingset.

“In my dreams everything is like it normally is except Dad is alive. He’s not with me, and I can’t see him, but I know he’s in his room or out doing something. I’m not even thinking about him, but I know he’s alive.” He kicked his legs out and then tucked them under. With each swing, Dessie got a little higher. He was gonna see how high he could get.

Elsewhere, “Always Be My Baby” acts as a companion story to “Lexapro.” Both engage with psychiatric therapy: the former from the perspective of a deeply flawed therapist; the latter from the viewpoint of an OCD patient in treatment. In both stories, prescriptions seem to harm as much as they help, and therapeutic techniques (even highly experimental ones) seem to be placeholders for whatever breakthrough or backslide may come next.

In “You’re Gonna Know My Name,” Lucy finds herself stuck in a derelict Nevada casino town. She dreams of bolstering her video reel enough to become a camera person on the TV show Cops. Her guerilla journalism sends her and her brother into an abandoned casino. There, they run afoul of a local cockfighting ring, and the town’s corrupt mayor. Fans of Willy Vlautin’s determined Nevada underachievers will find much to love here.

“Ride With Me” brings this survey of America at its most lonesome and desperate to a perfectly strange conclusion. Here we find a woman obsessed with the podcast “Serial” who uses it as a hook (along with cocaine) to seduce another in what seems to be a long line of pizza delivery drivers. This time, her come-on leads to what may finally be a true connection, as she and her hopeful lover take off for Baltimore from South Texas in the middle of the night.

The undercurrents of menace, humor, and pathos in So Much Heart strike me as particularly resonant with this American moment. In each of Buxton’s stories, we meet people who are hanging out at the end of the rope that circumstance’s endless choice-fucking has birthed them. They’re all trying like hell to pull themselves back, to what they often do not know or care, so long as it is not where they are. The book offers greater love for that never-ending search than I’ve been able to discuss or adequately capture here. Buxton’s biographical note indicates that he also makes a living as a social worker. One selfishly hopes that he continues his work in that field, as it seems to inform, inhabit, and enliven the stories he has to tell. And that’s to the reader’s benefit.

JPKS is a songwriter living in Fayetteville, AR with his wife Megan and their three dogs. His projects include solo work, the band Water Liars, and the duo Marie/Lepanto (with Will Johnson).

More Reviews