Words Fail Me | Nathan Dragon’s The Champ

Reviews

By Stephen Mortland

On November 5, 1979, William Gaddis, reticent and guarded, stood at the head of a long narrow room at St Michael’s College in Colchester, Vermont. He would have preferred to be many other places; he would have preferred, most of all, to have been home, in his study in Piermont, outlining paragraphs on the new novel. He had only recently admitted, in a letter to his daughter, that he was “thinking seriously about thinking seriously about starting another book.” There was always more work to do. Besides the novel, he had a deal with his endodontist and needed to rewrite two pages of the doctor’s sloppy prose to cover the cost of his root canal. He would have preferred to be elsewhere, and he told the students as much, telling them, at the outset of his lecture: “I feel like part of the vanishing breed that thinks writers should be read and not heard, let alone seen.” He shared this same quip, verbatim, in a speech he gave three years earlier when receiving the National Book Award for his second novel, J R. Watching the blank faces of the students gathered before him, he did not imagine that they had much patience for his inhibition, and he expected most had not read his books. They were waiting to be told significant things, waiting to be given profound axioms, and he did not know what to say to them. He borrowed further from his National Book Award speech. He talked about the tyranny of facts, about suicide rates; he talked about the Green Bay Packers. “Before 1800, the main problem about being a writer was to keep writing well. By the end of the century, the main problem was to write well enough to establish or to maintain the position of being a writer,” he said, quoting something he read in a preface to a novel by Gorky.

Throughout the lecture, Gaddis was funny and affable. He was clumsy enough to be forgiven his genius. Failure was his subject—failure as the defining theme across the history of Western (particularly American) literature. Moby Dick and Billy Budd, The Red Badge of Courage, The Jungle, Sister Carrie, Grapes of Wrath, all of Hemingway, The Bell Jar, Play It as It Lays. “All our novels,” he said, “are about increasing frustration, alienation, insecurity.”

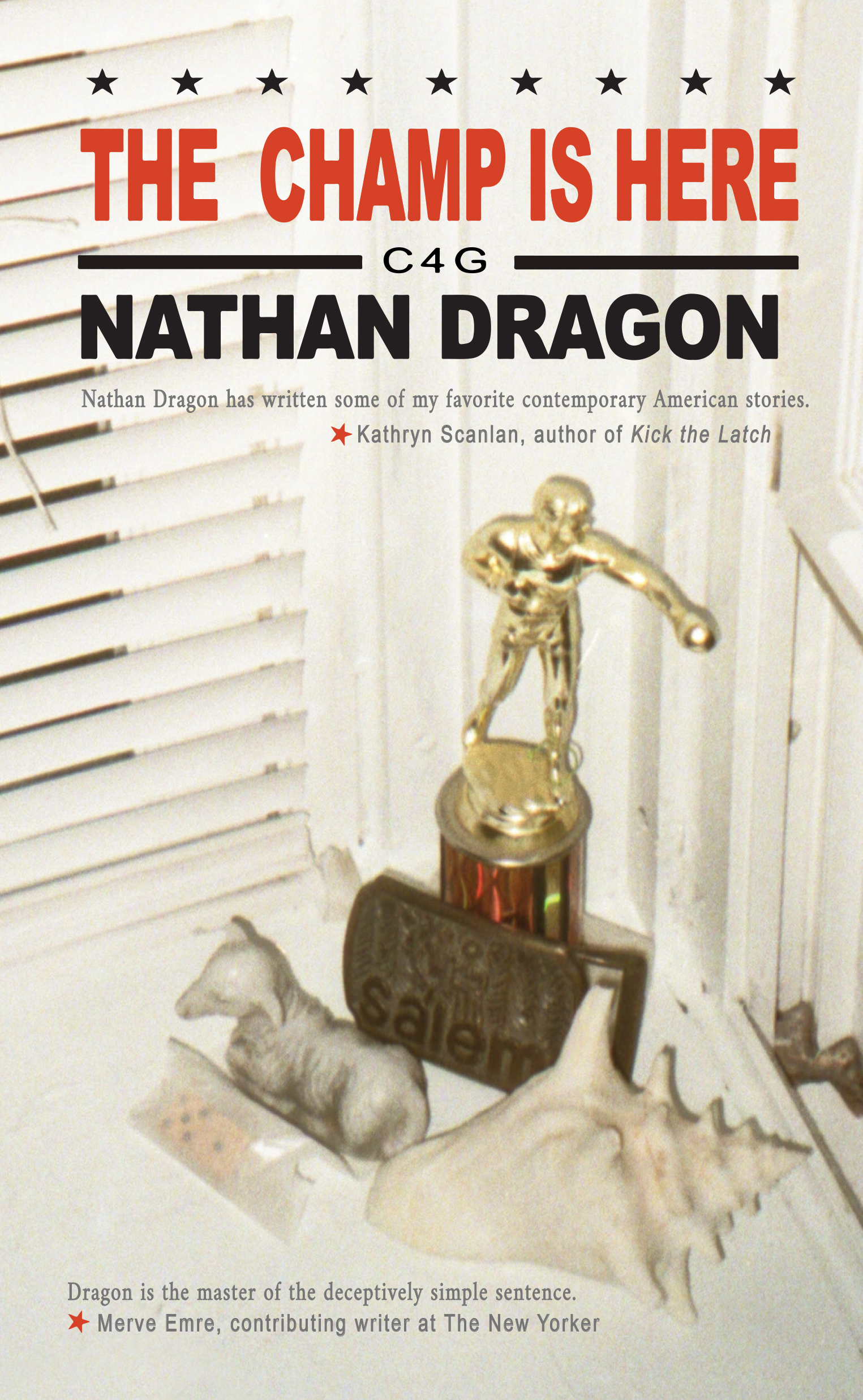

Nathan Dragon’s debut collection, The Champ Is Here was released in December from Cash4Gold Books, a newly founded independent publisher that appears, from their early releases, to be championing books that fit nicely among Gaddis’s lineage of fuck-up literature. The Champ Is Here orbits the domestic life and the psychological flux of its central, unnamed protagonist. The stories are interconnected, but their connectivity is loosely fitted and unobtrusive. It reminded me, while reading it, of the structural gambit in Hemingway’s first collection, In Our Time—there are conjoined narrative threads between the stories, and these threads undeniably overlap and intersect, and yet there is no clear, reducible order, no synchronized variation between the different parts. Sometimes our protagonist is the narrator of the fiction, while in other stories he is kept at a distance, in the third person. We gather that he is living in Middle America, in a small town with rural realities, in a house with neighbors, surrounded by lawns. He has a partner, he has a dog named Jacques. He works, sometimes, in roofing; he cuts plastic decking; sometimes he drives between empty houses, checking the state of the houses for a property management company. He worries over a woodpecker. He thinks about Jesus. He frequents restaurants and grocery stores and waits at home for his partner to return from work. He considers what sort of man he has become and what sort of man he might become still later. The interconnected nature of the stories is not concerned with establishing an overarching narrative. It attempts, instead, to pull the fractured bits and bobs of a life into a panoramic whole without erasing the signs of fracture.

Reading Dragon, I am reminded of language poets like Ron Silliman and Bob Perelman, but even more I am reminded of the wily prose poems of Charles Simic or the downtrodden probing of Townes Van Zandt and Gram Parsons. Dragon’s fictions blur distinctions between dialogue with invasive interior thoughts. They marry colloquial, spoken language with hyper-constructed literary sentences. They are concerned with objects and material—with the surface of things, the details of life—but the engine of the stories is always the undersong, the rhythm, the language. They are strange stories that mine the strangeness of domestic life and of spoken language like the writings of Sherwood Anderson or James Purdy.

Dragon has been publishing these stories in literary journals, online and in print, for the better part of the last decade. It is difficult to position his work, to know where to place it and how. Categorizing the fictions as experimental or poetic, though true, threatens to reduce them to a sphere of lyric stoicism that discounts the humor of the work and the groundedness of the material. It is easiest (closest at hand, at least) to locate Dragon’s fiction alongside the work of certain American writers influenced, to one degree or another, by the unique compositional approaches of editor Gordon Lish—writers like Christine Schutt, Garielle Lutz, Jason Schwartzman, Eugene Marten, Barry Hannah, Kathryn Scanlan, and Diane Wiliams (Williams edits NOON, where Dragon’s stories have regularly been appearing since 2017).

The stories in The Champ Is Here are often very short. They rarely stretch longer than two or three pages. To achieve this economy, the prose is compressed—sentences are shaved and shaped. Great attention is paid to each word, and nothing feels accidental. The stories are tight narrative objects—concrete and crystalline. It is compressed writing with a wide lens, an expansive scope. Unexpectedly, we pivot. Our attention is recentered. Often, in their final sentences, the stories express sentiments that radically recast what we were previously reading. Compression and scope are forced into alignment and they leave behind these strange, tingling fictions, as evasive as they are precise.

Gaddis, in his lecture at St. Michael’s, focused on a particularly American brand of failure—the failure that results from an unspoken and internalized need for success. Not success as a goal, but success as a state of being. Dragon’s collection, albeit slippery and resistant to easy categorization, fits neatly into the lineage Gaddis outlines. The unnamed protagonist wrestles against various insecurities and failures—some substantial and some less so. He is not failing passively, but is aware, as he fails, of his own weakness. Among his failings, there is never despair. He wants, desperately, to love. He wants—in spite of his own shortcomings and the shortcomings of the world around him—to love himself and love the world and love his partner and love his dog. There are failures of masculinity. He wants to be a hunter, a predator. He looks at himself in the mirror, touching his thighs and his chest, imagining he’s seeing a cowboy, a Man of the West. He wants to be “the champ.”

But now he’s thinking, I’ve gotten nothing done—he is thinking about a mediocre attempt at something maybe interesting . . . He feels embarrassed. Is he supposed to be embarrassed by this? He wants a way of life. Something that originates with him. (“A Life in A Small House”)

There are failures of community: good samaritans leaving piles of peanuts on the sidewalk despite the angry letters of aggrieved neighbors, or the neighbor who threatens to kill herself when she finds herself too weak to take out the trash and with no one to help her. Nowhere are failure and love more intertwined than in the trappings of domesticity:

They fell in love and out of sleep, holding hands.

Whatever they had wanted this coming evening was going to come and they’d have to sit with it long enough because there wasn’t much of a choice.

A decision needed to be made.

Gently.

So for once, no bother at all.

One of them didn’t mention something that shouldn’t have been mentioned to the other—a thing that can happen sometimes and is usually not too bad but can be. Ultimately a thing best left alone that sometimes isn’t.

Better off not asking what. One of them thinking that the other must have said something. (“Licking the Spoon”)

Beneath and behind these failures is another more endemic: the unrelenting disappointments of the modern, developing world. A world that poisons birds and tears down houses. A world that makes it difficult to bridge gaps, make connections. And the challenge, in the face of this disappointment, is learning to love the place you are when the place you are is sometimes cruel, sometimes senseless.

What makes Dragon’s approach distinct, and distinctly moving, are the ways failure infiltrates the language and the syntax of the stories themselves. The stories in The Champ Is Here are formally rigorous—and by this, I do not mean they are rigid or unbending. What I mean by formal rigor is that the stories use form as a way of thinking. The ideas in the text—the questions suggested by the psychology of the text—are explored in the form of the text. From story to story, patterns emerge that are not first and foremost thematic or narrative patterns—these patterns are primarily structural, syntactic, and rhythmic.

I thought about Kafka’s aphorism “A cage went in search of a bird” while I was reading Dragon’s stories, though I don’t know if I thought about the aphorism in the way Kafka intended. In September of 1917, in the pastoral town of Zürau where his sister Ottla lived and worked at the farm of her brother-in-law, Franz Kafka retreated to convalesce in the wake of a tuberculosis diagnosis. Zürau was a small bohemian village, with fewer than 350 residents, no electricity, no running water, no paved streets. Cats played with goats in front of taverns. Cows ambled alongside houses. Kafka watched five penned bulldogs from his window and named them, in his diary, Phillipp, Franz, Adolf, Isidor, and Max. There were no coffeehouses, no movie theaters, no bookstores, no newsstands, no post offices, no telephone in the village. It was an isolated corner of a struggling country in a shadowed corner of the world, and Kafka was, more or less, happy there. “The freedom, the freedom above all,” he wrote in a letter to Max Brod. The landscape was hilly, surrounded by farmlands and hop gardens and clusters of thick trees. The air smelled of manure. Nearly every day, in the late morning, after waking and drinking a glass of milk in bed, the convalescing Kafka—stripped to the waist—carried an upholstered chair to a little hill near the farm and spent the afternoon lying in the sun. For the sake of his ailing body and his anxious mind, he had decided to abstain from literary work. And yet, despite his commitment, refusing to write, he began to write. He recorded notes and diaristic reflections in a series of blue octavo notebooks. Inspired by his recent reading of Pascal’s Pensées, he wrote aphorisms. “Beyond a certain point there is no return. This point has to be reached,” he wrote. “It isn’t necessary that you leave home,” he wrote. “Sit at your desk and listen.” One scholar, describing the aphoristic writings, said, “Much remains fragmentary: again and again, scattered sentences that trail off into nothingness.”

Dragon’s sentences are full of false starts. We feel him twisting the language, doubling back, trying it another way. “Writing now,” he writes in “A Year in the Face,” “I remember how having to skip lines when writing by hand a long time ago helped me think.” The sentences stumble and stutter, embracing absence, leaving space for what cannot be put into language.

Everything that is said or that can be said about something, whatever it is, reduces it. That thing that is being referred to, whatever was said about it—and even the relationship between that thing being spoken about or referred to and whatever this thing is related to is reduced when anything is said about any of it.

Something is or is-like some something specific, but not only that.

Happens or doesn’t; is whatever it isn’t; skirting around it.

It can be like a lot of things, like what it’s made of, or nothing related to it at all.

With that being said, there’s probably more to it.

For example: The lake smells fresh like dirt and the ocean smells like the ocean. (“Whatever It Is”)

It is not the precision of the descriptions that make Dragon’s fictions most compelling, it is the imagined hand of the author trying to be precise, the intention toward precision, and the ultimate failure of language—the need to stretch and abuse it—that makes the work feel true.

“A cage went in search of a bird,” Kafka wrote, and like all the aphoristic work, it is, by design, hard to say what he meant by it. There are all sorts of cages in Kafka’s writing and thinking—social cages, judicial cages, psychological cages—but while reading Dragon’s stories, the aphorism came to mind as I was thinking about the cages of language. The stories are cages and, as in Kafka’s aphorism, it seems they began with the cage. The cage came first—the structure, the form, the syntactic priorities—and once the cage was established, it found itself a bird: something living, something moving, something curious.

Stephen Mortland is a fiction writer. His work is published in New York Tyrant, Fence, and Chicago Review. He is also a frequent contributor to NOON Annual. He lives in Salt Lake City, Utah.

More Reviews