The Mysteries of Reading and Writing | An Interview with Amina Cain

Interviews

By Mark Haber

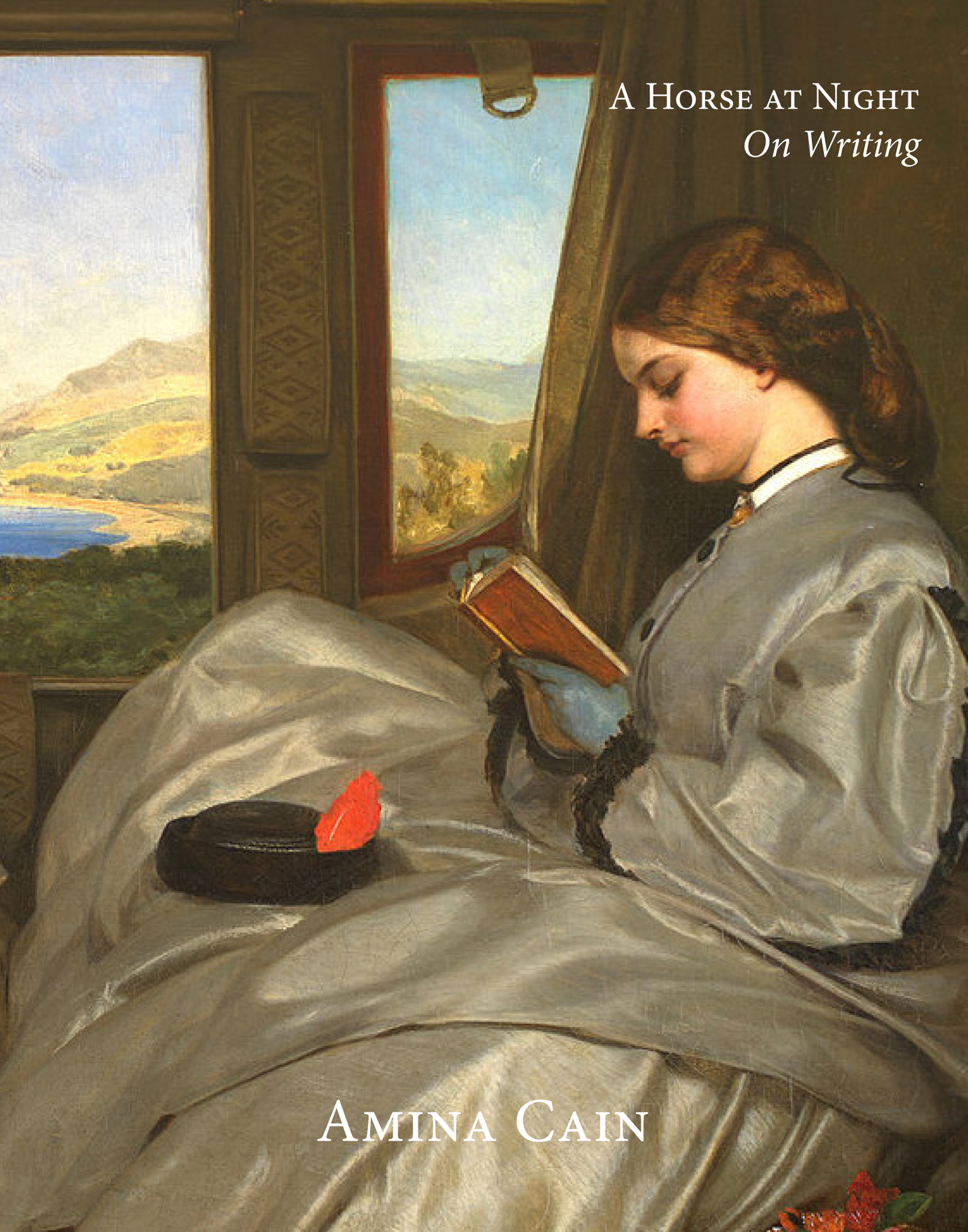

Amina Cain’s new book, A Horse at Night: On Writing, is an exquisite and spellbinding book about reading and writing, books and writers, experience and place. Cain asks such questions as: Where do we go when we read? When we write? We’re outside of ourselves, yet, perhaps, more true to our inner selves than any other time. She writes about painting, meditation, and influence, as well as friendship, geography, and the literary canon of her life, all with a wise generousness. Part essay, part memoir, part literary criticism, and wholly a love letter to books and their transformative impact, A Horse at Night is simply stunning.

I was lucky enough to ask Amina some questions via email and share her responses below.

Mark Haber: Although writing is in the title, I feel like your book is just as much about reading and how the act of reading intertwines, often unconsciously, with writing. Do you see reading and writing as two separate acts, independent of each other, or are they sometimes (perhaps always) connected?

Amina Cain: The answer must be different depending on the person, but for me they’re almost always connected, especially when I’m reading a book I love or with which I feel in conversation or kinship. A few years ago, I realized that I became a writer for the very reason that I’ve loved certain books so much—like Duras’s The Ravishing of Lol Stein, Lispector’s The Apple in the Dark, Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, Renee Gladman’s Ravicka series, to name a few—that I’ve felt compelled to write back to them. Not directly, necessarily, but unconsciously, like you say. They open a space for me, not in terms of story, but of atmosphere, imagery, language, and narrative voice. I’m not sure I’d get to these spaces without them. When I read these books, I am completely energized and taken over in this really blissful way. And, if I can’t write, if I’m too busy with work, for instance, I feel agitated.

MH: A lot of books about writing can be too analytical. I love that you treat reading as a great mystery; you don’t try to dissect or untangle the riddle as much as examine the act itself in a very tender way. Was this a conscious effort on your part, or is it simply how you approach reading and writing?

AC: Not much that I do when it comes to reading and writing is conscious. I know that might come across as pretentious, but it’s just the way it is for me. Of course, I make conscious choices when I write, and I’m very interested in process, but I also feel my way toward things, toward what I write, toward my thoughts about what I’m reading. I interviewed another writer about her book a couple of years ago, and one of the publications I sent it to rejected it, saying they didn’t publish interviews on craft. I was surprised because I don’t see myself as a writer who is interested in craft. I actually hate the word “craft” as it relates to writing. I hate the idea of the writer’s toolbox and of approaching writing in that way. To me, reading and writing are great mysteries, and while I like to explore the mystery, writing would bore me to no end if I were always thinking about my “tools.” I do believe that, as writers, we learn a lot about how to write through reading, but again, it doesn’t only have to be on a conscious or studied level. I’m a big believer in absorption, which retains the mystery of the reading—and writing—experience. So I’m certainly not analytical about it. That said, the form of a book is infinitely interesting to me, as are the forms of its sentences. I’m interested in the experience of reading and writing: each is a kind of territory. I see this as different from craft.

MH: Was there a specific seed that inspired you to write A Horse at Night, or did it come about from different ideas of books and writing that collected over time?

AC: On the Dorothy website, it states that they are a publishing project “dedicated to works of fiction or near fiction or about fiction.” I’ve always wanted to write a book about fiction for them. As I’ve said in other moments, they’ve helped me go further in my exploration of fiction, both as a reader and a writer, and in my conception of what is possible within it. They’re wonderful editors; I love what they publish. In that way, A Horse at Night has always felt like a Dorothy book. I’d say that’s the seed that inspired the book.

But it came about too, I think, because of The Errata Salon, a talk/lecture series created by writers Colin Dickey, Jason Brown, and others at Betalevel, a beloved arts space in Los Angeles’s Chinatown. I went to many of those talks, gave some myself, and co-curated and co-hosted the series with writer Ariana Kelly for awhile. It was this kind of casual, beautiful education on writing nonfiction. The talks/essays were amazing, and the energy of them drove something for me in the writing of my book. Around that time, I also read a book on writing I liked a lot: The Näive and the Sentimental Novelist by Orhan Pamuk. It talked about reading and writing in a way I felt close to and inspired by—again, in terms of territory and experience. Then there’s just the fact that writing and reading make up so much of my life. I wanted to write about that.

MH: You make a really strong argument about the interior life, how it’s just as authentic as the physical world. Could you talk a bit about the importance of selfhood as it relates to books and writing?

AC: So often, my favorite thing about a short story or novel is the inner life of its narrator or characters. It’s another territory you can enter, just as you might enter a landscape or setting. But, for me, it’s almost always intertwined with the physical world. Interiors and exteriors will probably always be a preoccupation for me as a writer. I don’t believe you have to know who you are in order to write, or know what the self even is, but I think you should be willing to enter the space of that unknown and have enough quiet around you, at least some of the time, to be able to do it.

MH: You have some great things to say about the idea of “perfection” in art. About the work of David Lynch, you write, “What makes Lynch a genius is that it is impossible to tell the flaw from perfection.” Literature is subjective of course, so one reader’s notion of perfection can vary widely from the person right beside them. I also think “perfection” may be more of an American phenomenon. But can you talk a bit about the joy and beauty in a work’s flaws? And why the flaws are sometimes “better” than the perfections?

AC: I think that what you can sometimes (but not always) see in a flaw is the complexity of what a work is attempting. You can see its reach: its craziness, its roughness. I’m interested in those qualities. I’m interested in polish too, but not at the expense of these other things. Alone, it can feel shallow. Maybe it’s better to think of perfection in a more expansive way—in terms of a work being complete in itself.

MH: There’s a mysterious space between the text and the reader/writer that you capture brilliantly in A Horse at Night. A space that could be called the “imagination” or “the self.” It’s not the page, and it’s not a physical space the reader/writer occupies. It’s somewhere other. I’m there when I’m writing and reading, and it’s almost impossible to put into words. I’ve also seen it in the work of Gerald Murnane, almost as an obsession. This is a very broad and philosophical question, but can you talk a little about this place?

AC: Your question takes me back to what I said before about what happens when I read a book that makes me immediately want to write. In that moment, there’s an intersection between the text and who I am as a person/writer. Reading itself is an imaginative act. In his writing on the process of reading, Wolfgang Iser said that a literary work has two poles, the artistic (author) and the aesthetic (reader). When I read, something is conjured for me; when you read, something is conjured for you. It might overlap, but it’s not exactly the same. If what is evoked sends me into a writing space, you might not recognize that space even if you’ve read the same book. And, if it sends you into a writing space, it will be different from mine. Maybe I write because I experience the aesthetic pull of reading so strongly. Often, I think I write purely to spend time in sentences and images. And it’s probably why I read. To me, that is the real perfection: to spend time in a space you can’t get enough of. That’s almost addictive, whether you’re reading or writing.

Mark Haber is the author of Deathbed Conversions, Melville’s Beard, Reinhardt’s Garden, and Saint Sebastian’s Abyss. He is also the operations manager and a bookseller at Brazos Bookstore in Houston, Texas.

More Interviews