The Ecology of a Scene | A Conversation with Lenny Kaye

Interviews, music

By Elizabeth Nelson

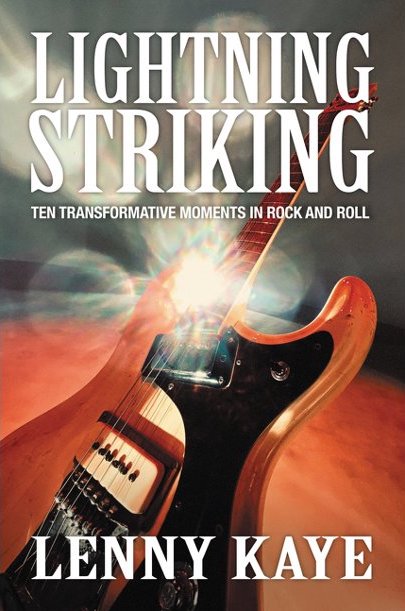

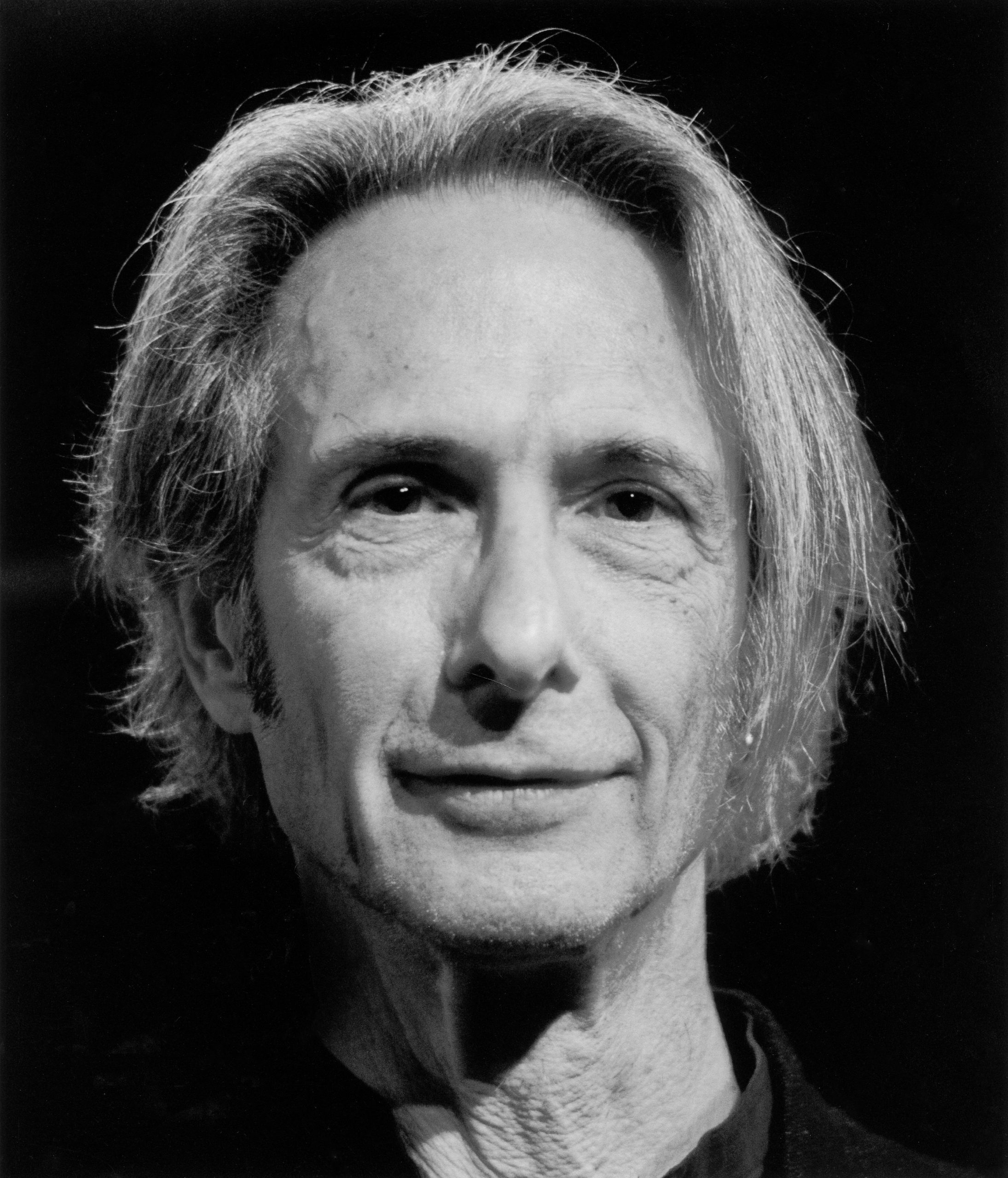

Over the course of his storied five-decade career as a musician, journalist, and historian, Lenny Kaye has been a kinetic force of nature. Whether serving as guitarist in the Patti Smith Group, writing the definitive biography of Waylon Jennings, or curating the much-fetishized garage-rock omnibus Nuggets, Kaye has demonstrated a omniscient knack for knowing where the action is and being a crucial part of it. His most recent book, Lightning Striking: Ten Transformative Moments in Rock and Roll, is a fascinating amalgam of carefully researched history and personal reflection, which focuses on the moments in twentieth-century music when scenes came together from Memphis to New York to Liverpool and the dynamics that catalyzed these seismic occurrences. With its combination of intellectual rigor and “I-was-there” insight, Lightning Striking is a remarkable work no one else could have rendered.

I was thrilled to talk to Lenny Kaye about his concept for the book, his storytelling methods, and what a lifetime in music has taught him about the grand and vaulting mysteries of the creative process.

Elizabeth Nelson: Lightning Striking is fascinating for a number of reasons, not least of which is its structure. It moves from the early 1950s through the end of the century and intersects with your own life and career. In that sense, it functions as both a thoroughly researched history and a memoir. Can you explain how you conceptualized this book and talk about the challenges and advantages of the approach you decided to take?

Lenny Kaye: Well, I’ve always wanted to do an overview of the history of the music that has nurtured me in my lifetime. I was part of that generation that grew up with early rock and roll, so Lightning Striking was a way to tell my own story without telling my own story. I wanted to keep the focus on the historical transformations within the music and tell the story of rock and roll through its flashpoints. But I also wanted to acknowledge that I had witnessed this history, experienced it and lived through it. Basically, I was able to walk alongside the tale I was telling. Of course, the tale I was telling was very much filtered through my own aesthetic—the kind of music I would play, the bands I was attracted to, and other areas that were fascinating to me, like race, gender and location. All of this played into how I viewed the music as it developed over my lifetime.

Lenny Kaye: Well, I’ve always wanted to do an overview of the history of the music that has nurtured me in my lifetime. I was part of that generation that grew up with early rock and roll, so Lightning Striking was a way to tell my own story without telling my own story. I wanted to keep the focus on the historical transformations within the music and tell the story of rock and roll through its flashpoints. But I also wanted to acknowledge that I had witnessed this history, experienced it and lived through it. Basically, I was able to walk alongside the tale I was telling. Of course, the tale I was telling was very much filtered through my own aesthetic—the kind of music I would play, the bands I was attracted to, and other areas that were fascinating to me, like race, gender and location. All of this played into how I viewed the music as it developed over my lifetime.

EN: Speaking of location, the book begins with this wonderful bit of scene-setting in the 1950s in Memphis, a city and era which exemplifies the cross-pollination of so many different musical styles and influential artists within this emerging marketplace. You have blues and country musicians, crooners, rockabilly artists coexisting, and there’s this wild overlap. They didn’t concentrate consumers using the hard genre distinctions that we have today. Can you talk about researching Memphis in the 1950s and what it taught you?

LK: I think everybody is aware of the Big Bang that took place in Sam Phillips’ studio in 1954, where all of these musics coalesced into one extraterrestrial being that seemed to represent them all. I believe Elvis was not Black rhythm & blues. But he wasn’t white country, and he wasn’t pop in the same way that, say, Bing Crosby was. He was all of it, and he gathered it together, perhaps unconsciously, in a kind of package that helped the mutation of the music become what it had promised. Previous to that, you could divide it into its tributaries, whether it be country boogie or R&B or straight blues or vaudeville. There was a flashpoint there: all of these aspects played into what the music would become.

In writing the book, I tried to find those moments where the music and its moment changed irrevocably. If you go through the book, you’ll see that each time that happens, there’s a singular juncture of time and space. When that little flashpoint—that locus of energy—happens, things are different. The smoke clears, and we’re suddenly on a new plateau. A new generation has formed. Again, these are not the only things that were happening—I didn’t cover them all. I didn’t talk about DJ Kool Herc on that playground in the Bronx. I didn’t talk about what was happening in Kingston, Jamaica, or Cologne, Germany. There were so many moments in time that contributed to the great tapestry of popular music, but these were the ones that initially resonated with me as a listener, a fan, and eventually, a musician.

EN: The idea of Elvis and Sam Phillips representing a cultural Big Bang is one we’ve been conditioned to accept, so it’s really interesting for you to emphasize how many other things were happening at that time. I wonder if the argument could be made that Elvis wasn’t necessarily the beginning of something but an apotheosis of a lot of things that were taking place simultaneously. Another example is everybody thinking that grunge begins with Kurt Cobain and Nirvana. In reality, there was all of this scene stuff happening that predated and led to that moment.

LK: I agree. A lot of times, when these scenes that I describe hit their moment, it’s because they’ve been growing for a certain amount of time before they get that definition—that name that defines each scene—almost to the exclusion of everything else that’s happening. I spent most of the time in the chapters on what leads up to the flashpoint, especially in the case of the Seattle chapter. We go back to 1986 and the beginnings of Soundgarden and what would become Pearl Jam and the Melvins. In a sense, Nirvana was a combination of all of these bands: Soundgarden’s angst, the Melvins’ incredible sludge of sound, and Pearl Jam’s sense of uplift. The same could be said of the Beatles. They came out of Liverpool learning the same R&B songs that all their contemporaries in the Cavern Club did. But the Beatles had one other thing those other bands didn’t: they were songwriters.

So all of these scenes gathered momentum in their first couple of years. They coalesced. Brian Eno has a great concept, which I borrowed, called “scenius.” It’s not really about the geniuses on that stage but the entire ecology of the scene: the people hanging out, the fashion, the ideas that come from the periphery, the social moment in time. What else is happening? What is the scene reacting to? Usually, by the time it acquires its appellation, whether it’s bebop, rock and roll, the British Invasion, psychedelic music, punk, or heavy metal, it’s been figured out.

What happens after the moment of conception is less interesting to me because then it requires a definition, which excludes as much as it includes. It becomes much more predictable. And even though there’s going to be a lot of great records coming out of it, the fact is that you pretty much know what they’re going to sound like. I like those moments in time when things are blurry—when nobody’s really sure of what’s happening. They’re trying out this; they’re trying out that; they’re experimenting; they’re making mistakes. That, to me, is when the inner being of these scenes truly comes into focus. And that process is almost more important and more interesting to me than the superstar who will encapsulate that scene.

EN: Something that comes up in both the Memphis and New Orleans chapters of your book is the significant influence of Bing Crosby. I find this fascinating because I don’t think most people associate him with acts like Elvis Presley and Ray Brown, but you make that connection. Can you say more about Crosby’s somewhat shadowy influence?

LK: Well, the shadow Crosby casts is quite long. Probably, by the middle 1950s, when he’s become more of a family-friendly icon, people had forgotten how innovative Bing Crosby was in the 1920s. In that era, he was subsuming Black American idioms into his music and self-presentation while turning himself into a true matinee idol. So I hear a lot of Bing Crosby in Elvis. I’ve actually written a book about Bing Crosby, Russ Columbo, Rudy Vallée, and the great crooners. It was an amazing adventure seeing how these artists changed the way singers approach the microphone, the music that they made as a result, and how popular that music became at a time very much before rock and roll had even been conceived.

Crosby kind of desexualized this over the years, but early in his singing career, the croon was a way for a man to sing to a woman in the woman’s language. That’s a very important part of the evolution of twentieth-century music. I really enjoyed extending my area of investigation and scholarship into the late 1920s and 1930s. It taught me a lot about how music continually evolves and takes root in many different ways. I mean, Elvis and Bing died in the same year: 1977. But whose death do we celebrate more? Must be Mr. Presley’s, but Bing—who is definitely not respected that much these days—did as much to modernize popular music as Elvis did.

EN: We have a tendency to think of the Beatles as having almost miraculously emerged from Liverpool, which is sometimes described as a bit of a cultural backwater compared to London or New York. You paint a very different picture of Liverpool in the early 1960s, describing it as a hub of Bohemian ideals—a forward-thinking environment—which sets the ascent of the Beatles in a more plausible context. Can you talk a little bit about that Liverpool scene and how it’s very different from the way it’s often portrayed?

LK: Backwaters and towns off the beaten path, at least as far as the music business is concerned, are where change usually occurs. Even in New York during the 1970s, it was almost like the East Village was a region—even a country—apart from the grander metropolis, where the music business had its headquarters. The Beatles figured themselves out away from the pressures of the music business. That they had to forge their own path is very important not only to their development but also to the development of what would become Merseybeat and the British Invasion. The Beatles and those bands weren’t slavishly recreating American hits, which is what was happening in London at the time. In London, they would find American hits and get one of their new teen idols with great little adjectives for names—Adam Faith, Billy Fury, Johnny Gentle, Marty Wilde—to cover them. The Beatles had to develop their sound on their own with their contemporaries at the Cavern Club.

Going to Hamburg at a very early age was huge for the Beatles, too. That was like the satellite town of Liverpool. There they could live it up, play their music six, seven, eight hours a night, and understand who they were as musicians and what they wanted. Again, what set the Beatles apart from most of the other bands in the Cavern was their songwriting ability. They really concentrated on that. Many of the Cavern bands were content to do their versions of American hits. But the Beatles definitely set out—under the tutelage of George Martin—to create their own sound and songs. And that’s really how that happened. If the Beatles had been in London, hanging out on Denmark Street, they might have sounded like everybody else. Again, most of these scenes begin somewhat under the radar. They have time to develop. This time to figure yourself out is so important.

EN: And this was true in your experience making music?

LK: Absolutely. For at least two years, the bands at CBGB were basically playing for each other. There were twenty-five people in the club, all of whom were in the other bands. You had the freedom and time to go up a blind alley, make your mistakes, trade band members with other bands, and figure out what to do with this amorphous sense of possibility given to you—how it might manifest, how you could learn to play it, how you could learn how to put it in a song. When you’re embarking upon something new, you don’t know where you’re going. If you have a destination, there’s no real fun in figuring it out, and it will be a cliché by the time you do it. All of these scenes coalesced like cosmic dust coming together to form a planet. To witness this happening in real time—that can’t be manufactured. And the industry has tried.

I’m worried that with the advent of the internet and the ability to sweep your fingers across the computer keys and travel anywhere in the world to see any band from any era, we’re losing appreciation of the time element. I know I had to get in a car and travel to San Francisco in 1967 to see what Big Brother and the Holding Company were doing, what the Grateful Dead were doing. Even if they had an album out, it wasn’t like being there, having the experiential immersion with the light show in the ballroom and the LSD.

EN: I want to talk a little bit about your relationship to a couple of scenes. You were part of the Bay Area scene in the 1960s and the Lower East Side revolution in New York in the 1970s. I feel like there’s this historical tendency to regard these two scenes as somehow oppositional: the industrial menace of the Velvet Underground compared to the utopian idealism of Jefferson Airplane, for example. Has that notional dichotomy sort of fallen away in recent years?

LK: Well, all scenes are somewhat reactive. If you’re going to have a peace-and-love scene like San Francisco, often the next one down the line will be a response to it, like the high-energy, politicized, very violently played music that emerged from Detroit around the same time. There’s always a sense of counter-reaction and figuring things out. But, with New York and the Bay Area in the late 1960s, there was a great deal of aesthetic overlap as well. When the Velvets started working with abstract dissonance, the Grateful Dead were doing something similar, moving their music past melody and rhythm into kind of a free-form sound-upon-sound. Ironically, both bands called themselves the Warlocks early on. But once you get past what each scene sounds like, you get to what it really is—a bunch of creative musicians coming together, having a place to figure things out, and figuring them out.

Plus, when you come right down to it, the San Francisco bands did not sound alike. They all had different personalities. Jefferson Airplane certainly didn’t sound like the Grateful Dead, and Quicksilver Messenger Service had their own sense of self. Tom Verlaine once said something very interesting about the CBGB bands. He said, “Each band was like an idea. Very different from each other.” But by the time the word “punk” was ascribed to Television, Blondie, Talking Heads, etc., the focus had turned to London. That’s when punk became capital-P “Punk.” You had a specific look, a specific style of music, and a very similar intent shared by all the bands. To me, that’s somehow less interesting. But maybe it’s easier to figure out on a mass scale. The English bands picked up the template of the Ramones—those fast eighth notes drumming, the simplistic and confrontational lyrics—and that became Punk. But in 1974, when the word was bandied around CBGB, it was more like renewal, starting over, not taking what was “then” but trying to interpret your “now.” For me, that’s what made the CBGB’s moment so creatively interesting.

EN: You’ve worked with so many creative titans over the course of your astonishing career, but the one that I have to ask you about—just because I’m so curious—is John Cale. What was it like making music with John Cale?

LK: (Laughs heartily) Well, John is a wild card. He’s very strong and opinionated and definitely doesn’t mind ruffling feathers. On Horses, he challenged us to go as far as we could go. If we wanted to record something live in the studio, he said, “Well, make sure you capture that moment.” He pushed us considerably. “Birdland” started out as a three-and-a-half minute poem that Patti set to Richard Sohl’s rambling music. We wanted to record it live because it also had some elements of improvisation to it. With John’s urging, the song just got bigger and bigger and bigger and lengthier and lengthier, and he forced us to get further and further out on the limb until we got to the magical take on Horses.

That said, I think John probably wanted to make a more arranged record. That was his thing at the time. He was very much into Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys, and we were kind of defending our turf and didn’t want too much production. If you listen to “Redondo Beach,” about a third of the way through you’ll hear a tack piano go “bang bang.” We had a big fight about whether the tack piano should be there. It never shows up again in the song, which is kind of cute.

John has a sweet heart of gold and is a really lovely person, but it was a challenge for all of us to understand how to make our debut record together. Of course, that’s something all groups confront. You’re removed from the live situation where you can play as loud as you want and, if you make a mistake, who cares because it’s gone in three seconds. Now you’re under the more scrupulous eye and ear of the studio. It’s the psychodrama of art and, to be honest, I don’t think you ever quite figure it out—translating this abstract sound you have in your head onto a piece of tape or a hard drive. It’s the translation of emotion that first has to go through a song and then through technology to reveal that emotion to the listener.

EN: I want to close this interview with a question that pulls from a few things we’ve already discussed. You were talking about using the internet—

LK: Which I use all the time now.

EN: And the internet is great and I’m all for progress, but you also mentioned how, in 2022, if you want to go check out a band from the 1960s, you don’t drive to San Francisco to experience it. You just hop on YouTube and check out some clips. As we careen headlong into corporate tech hegemony, I wonder if there’s the slightest bit of anxiety that this will make it difficult for scenes to emerge organically. When everything feels so consensus-driven, how can we array ourselves in such a way that lightning can strike again?

LK: I’m hard-pressed to name a specific geographic place where that might happen now. The world is smaller, and I think that makes people more self-conscious about their art. Perhaps it will homogenize art to some extent. Even if you travel to another continent, you’re likely to hear pretty much the same music that you’re listening to at home. But I also believe in human inventiveness. I’m wondering whether scenes might not develop within virtual geographies. On the internet, you find like-minded people—or people doing certain things with certain tools with certain desires and ideas in mind— then connect in a kind of virtual setting and do your work for each other until it gets out into the universe.

I’m not sure if I’ll be participating in anything like that because, to be honest, it requires a grasp of technology that I’m not that interested in acquiring. But I do love some digital technology. ProTools has been a great boon, especially for someone who likes to edit as much as I do. In the 1990s, I remember trying to put two different piano parts together and the engineer telling me, “Come back in three hours. We’ll have it done then.” Now, you can flip it, turn it around and upside down. I mean, all of these things change the shape and scope of the music. You’ll be run over if you’re trying to stand in the way of progress. So, I’m all for the growth of new ways and means of making music because then the music will also evolve and progress and become much different.

Still, the same things are at the core of every great song, no matter the era, age, or intent of the person writing. What one would like to find in the world of love, what emotion is driving the songwriter crazy, how one can become who one wants to be. These are the building blocks of all great songs. As long as the human race can sing and make those notes into something that represents deep emotion, true expression will be the constant.

Elizabeth Nelson is the singer-songwriter for the Washington D.C. based garage rock band the Paranoid Style, whose five wildly-praised releases on New Jersey’s Bar/None Records have been described as “glam rock for the end times.” She is also a regular contributor to the Ringer, New York Times Magazine, Oxford American, Pitchfork, and Lawyers, Guns & Money.

More Interviews, music